Rick

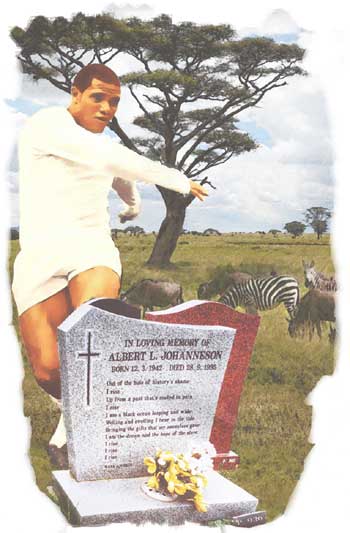

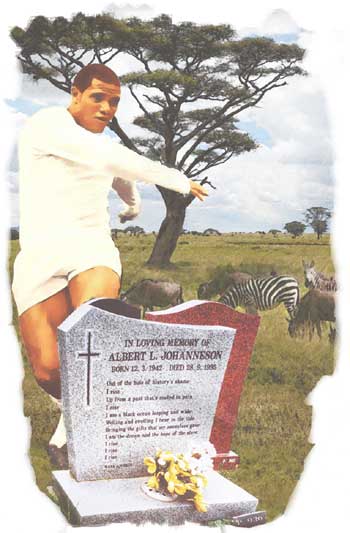

Broadbent from Looking For Eric: 'In a quieter part of West Yorkshire

is Lawnswood Cemetery ... The man in the office is incongruously cheerful

and wears a bright orange tie ... "You want to see Albert ... We

get quite a few people wanting to see him" ... He leaves me in peace

and I kneel before the mottled grey monument to Albert Johanneson. There

is part of a poem by the writer, actress and civil rights activist Maya

Angelou inscribed in black on the stone. It is a poignant and apt epitaph:

Rick

Broadbent from Looking For Eric: 'In a quieter part of West Yorkshire

is Lawnswood Cemetery ... The man in the office is incongruously cheerful

and wears a bright orange tie ... "You want to see Albert ... We

get quite a few people wanting to see him" ... He leaves me in peace

and I kneel before the mottled grey monument to Albert Johanneson. There

is part of a poem by the writer, actress and civil rights activist Maya

Angelou inscribed in black on the stone. It is a poignant and apt epitaph:

Out of the huts of history's shame

I rise

Up from a past that's rooted in pain

I rise

I'm a black ocean, leaping and wide

Welling and swelling I bear in the tide

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave I am the dream and the hope

of the slave

I rise

I rise

I rise

'A couple of lines have been omitted: "Leaving behind nights of

terror and fear, I rise into a daybreak that's wondrously clear."

Maybe they would have hurt too much, as the nights of terror and fear

ultimately proved too numerous for Johanneson to bear ... It is part of

history's shame that Johanneson, the flying winger for Leeds in the 1960s,

a South African who brought numerous gifts to the British game, ended

up a slave to his depression. The black ocean had drowned himself in booze

and drugs.'

There are countless examples of gifted young players who failed to build

on the potential of their early days, hapless victims of their own, innate

Achilles' heel. Fame is a spiteful suitor for those without the good sense

to look beyond its surface sheen. Few stories, however, can quite match

the tragic undertones of that of Albert Johanneson, whose spectacular

skills lit up the British game with Leeds United, the Great Unloved. He

sank without trace just as the star of Don

Revie's Whites soared ever higher in football's firmament.

It's a heart-rending story, one of the saddest in United's roller coaster

history, but it's essential in any story about Albert Johanneson that

one differentiates fact from fiction. Lazy journalism makes it all too

easy for the two to get mingled, with gossip repeated so many times that

it ends up becoming the accepted 'truth'.

When Johanneson's daughter, Alicia, read the first version of this document,

she was moved to write: 'Some of what you have posted is true, while some

of it is not.' She pleaded for me to 'stop perpetuating the myth/lie that

no one knows the whereabouts of Albert's family ... Those who needed to

know are aware that we went to live in Jamaica for many years, and are

now alive and well living in the United States where we continue to revere

our now deceased loved one.

'Furthermore, the so-called "former family home in a desperate Leeds

area" was never "boarded up". I doubt the people of West

Lea Gardens would take kindly to you calling their neighborhood a "desparate

area of Leeds", and I reiterate that my former home was never boarded

up as if it were an abandoned dwelling situated in a ghetto.

back to top

'Over the years I have become increasingly sick and tired of reading

what I know to be untruths about my father and I would be most grateful

if your website would at least make an attempt to begin to set the record

straight. The way in which my father's career and life ended were indeed

tragic, which you have pointed out, but as you have also stated, he too

was a wonderful football player for his day and time.

'If you care at all to frame Albert in the light of his humanity,you

may also add that he was indeed a good father and like most mortals living

on this earth was a complex and decent human being, the latter quality

of which the press is often unwilling to admit, while insistently savouring

his unfortunate addiction to alcohol.'

Hopefully, this document sets the record straight about one of the greatest

footballers who ever played for Leeds United and does Alicia's father

justice.

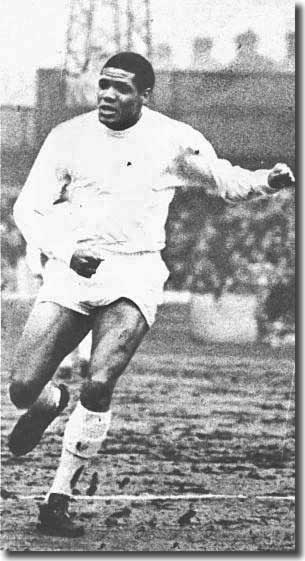

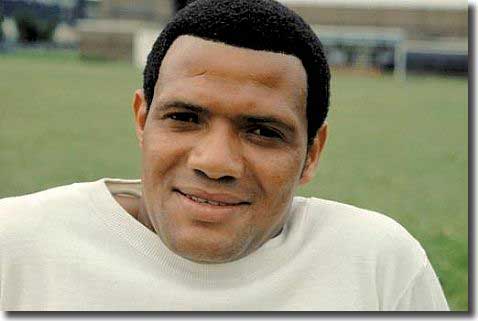

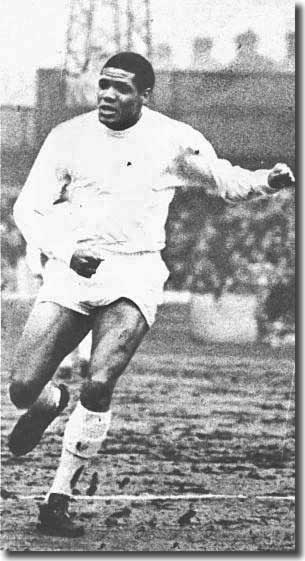

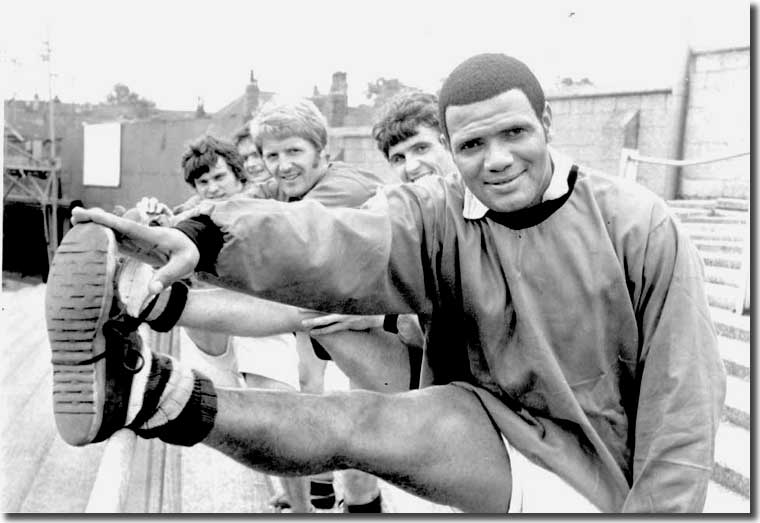

Johanneson was a trailblazer for the black footballer in Britain, a silky,

elegant magician, who brought style to a team that was otherwise the epitome

of prosaic Northern obduracy. That he should be such a shining beacon

in the dark satanic mills of West Yorkshire is a wonder, indeed.

News of his demise prompted this evocative obituary in the New York

Times, penned by Rob Hughes:

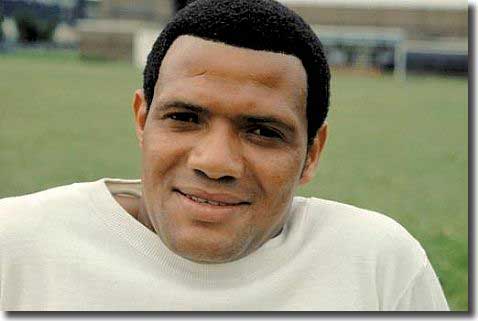

'Albert Johanneson, a delicate craftsman of the wing who thrilled thousands

for a decade, died in solitude last week.

'His body was found Friday by policemen who entered his tower block flat

in Leeds, England. It may have been there for two days but, though Johanneson

was only 55, the death certificate will read "Natural Causes".

That is an official lie. Albert Johanneson, born black in South Africa,

was a man, a star, who was born and died a victim of apartheid.

'Articulate mainly with a soccer ball at his feet, he moved with quick,

wispy control. No one tutored Albert, and few could work out the mechanics,

the improvisation nature put into him. Albert could trick most white men

he played against. Yet he remained socially subservient to the end.

'Discrimination conditioned him. He aspired to nothing more than being

a cobbler,  a

mender of shoes in Johannesburg. And though he was lifted from that by

an ability to put boot to ball, the upbringing crippled his self esteem.

His social stiffness was more than shyness. His marriage failed ... From

time to time, when the Leeds United team he graced held reunions, people

tried to invite him. When he could be found, he might promise to turn

up, but those were promises diluted by alcohol and methylated spirits.

a

mender of shoes in Johannesburg. And though he was lifted from that by

an ability to put boot to ball, the upbringing crippled his self esteem.

His social stiffness was more than shyness. His marriage failed ... From

time to time, when the Leeds United team he graced held reunions, people

tried to invite him. When he could be found, he might promise to turn

up, but those were promises diluted by alcohol and methylated spirits.

'Johanneson ... was on the threshold of manhood before he dreamed of

football. He was recommended to Leeds by an African school teacher who

saw him kick a ball for the first time at 18 and marvelled at the uninhibited

innocence.

'Belief, next to talent, is the sportsman's triumph. Johanneson could

not summon it consistently. Some insinuated that he was too timid to impose

his flair, but Billy Bremner ... recalled: "Albert had no confidence.

He could play, he was bloody quick, and Bobby Collins could sometimes

get him up, get him going. But it was as if Albert couldn't believe it

was happening to him, as if he thought a black man wasn't entitled to

be famous."

'South African apartheid had its English abettors. There were spectators

who bated Johanneson with vile Zulu chants, full-backs who kicked him

because they thought black men lacked courage. The stigma stuck to Johanneson.

After a series of leg injuries, he slipped down to lower division soccer

with York City, and succeeding blacks were branded cowards.'

Those who speak fondly of Johanneson are legion. Indeed, it is almost

impossible to find anyone who considered him anything other than a shining

example of all that is best about humanity. His proponents also denounce

as fabrication the pat, easy indictment of cowardice that is so often

laid at his door.

Norman Hunter: 'He was braver than many people gave him credit for, and

had the scars on his legs to prove it. On his day he could skin any full-back,

but he lacked the consistency and it was unfortunate that Albert was around

at the same time as Eddie Gray. He was one of Don Revie's most promising

signings but when Eddie got a grip of his place on the wing, something

had to give and Albert found himself in the reserves.'

Billy Bremner: 'I would like to say what an excellent player he was.

He was frightening on the wing and used to turn defenders inside out.

He was fast, clever with the footwork, very accurate with crosses, and

had a terrific shot. I always thought that he did not get a fair deal

from the media because he was black. They were forever on about being

the first black player to do this, or the first black player to do that.

They completely overlooked the fact that he was a terrific player and

deserves recognition as a human being and professional footballer.'

Don Fletcher, a United fan from Castleford, on the BBC Radio Leeds site:

'In those days I spent most of my school holidays camped out at Elland

Road, loaded down with scrapbooks, doing my utmost to get every photo

signed by as many players as possible. Some players would only sign one

at a time, but not Albert, he would always try to sign a couple at least.

Then one day I hit the jackpot. Unfortunately for him, Albert was injured

and was excused from training, which was held on the training pitches

where the Fullerton car park is now. As he got nearer to me I quickly

tried to search through my books for the best photo for him to sign. Upon

seeing this, Albert asked how many I had, to which I replied "quite

a few". Not a problem for Albert, he stood there and signed every

one in my book, 11 in total! My memories of Albert Johanneson are those

of a warm, kind gentleman who had an exceptional talent, which he displayed

on the football pitch. May he continue to rest in peace.'

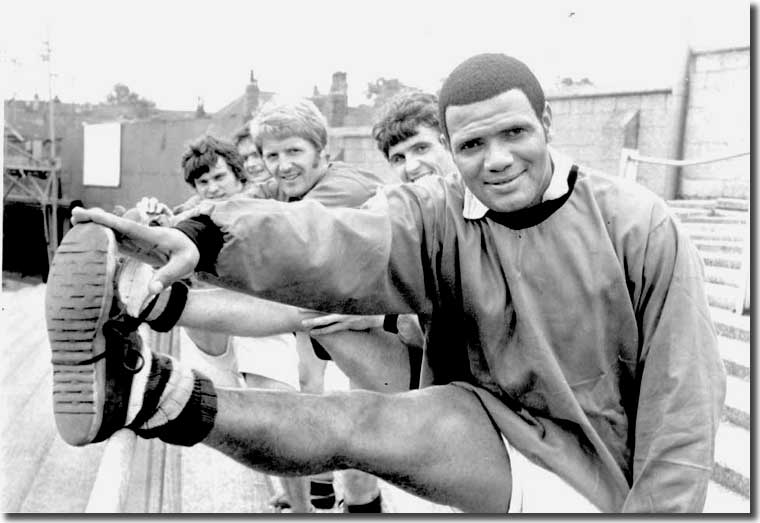

Not for nothing was Albert Johanneson characterised as the Black Flash:

he had God given pace and natural skills, including a 'bewitching side

step'. When he was bearing down at speed on a back pedalling full-back,

unable to fathom which way he was likely to go with his dazzling sleight

of foot, he was a wonder to behold. A lithe, subtle footballer with the

natural grace of an African athlete, Johanneson was 'blessed with blistering

pace, skill on the ball and a terrific shot', according to David Saffer,

he 'caused havoc for defences with his dazzling runs and crosses from

the left flank ... one of the most dangerous wingers around'.

back to top

Rob Bagchi and Paul Rogerson: 'He was a quick, strong runner and a clinical

finisher. He ended up with a strike rate of more than one goal in three

appearances, a ratio most out and out centre-forwards would consider as

satisfactory. For a winger it was sensational. For all the flaws in his

game, which became more explicit as the quality of the players around

him gradually improved, and the feelings of inadequacy that sabotaged

his personal happiness, Albert Johanneson was taken to the Leeds fans'

hearts because he lit up Elland Road in its age of austerity and his displays

offered a tantalising glimpse of what lay ahead once all the tedious hard

work had been done.'

Johanneson was a fresh, South African breeze, blowing through the claustrophobia

and dark underbelly of West Yorkshire football in the 1960s. At his best,

he was an uninhibited, natural artist, who could be relied on to attempt

the unexpected. He was an erratic, unpredictable genius, who brought colour

and flair to an anonymous combination of triers, lighting up the dark

corners of their world. The Black Flash was a unique, magical talent.

Albert Louis Johanneson is generally reported to have been born on 13

March 1940, in Johannesburg, South Africa, although his gravestone indicates

1942, which seems the likelier date. For one who appeared to have a natural

aptitude for the game it is amazing that he reportedly didn't kick a ball

until he had turned 18. He even claimed that football only inspired apathy

in him when he was growing up.

Having found his vocation, Johanneson rapidly made a name for himself

with Germiston Coloured School and Germiston Callies. A school teacher

from South Africa's former Transvaal province recognised his talent and

recommended him to Second Division Leeds

United in the winter of 1960/61 and he was offered a three-month trial

at Elland Road.

Part of the reason why Leeds was the preferred option was that they already

had one black South African winger on their books; 27-year-old Gerry Francis,

also hailing from Johannesburg, was the first black player to turn out

for the club. After joining United as an amateur he signed professional

forms in July 1957, though it was October 1959 before  Francis

made his first team debut. He struggled to hold down a place, but he was

given an extended run in 1960/61 and his presence at Elland Road made

it easier for Johanneson to settle into this new, alien world.

Francis

made his first team debut. He struggled to hold down a place, but he was

given an extended run in 1960/61 and his presence at Elland Road made

it easier for Johanneson to settle into this new, alien world.

The signing of Francis made news in the game at a time when there were

almost no black footballers in Britain. Bagchi and Rogerson: 'In his meticulous

survey, Colouring Over the White Line, Phil Vasili rights the common

misconception that the emergence of black footballers in England was a

1970s phenomenon, rehabilitating scores of forgotten pioneers such as

Arthur Wharton, Walter Tull and Roy Brown, and movingly recreating their

quiet heroism in the face of the country's prevailing xenophobia. Ever

since the 1920s, casual racism had consigned generations of black players

to the peripheries of the game. There had been some significant breakthroughs,

but after 1945 the pre-war trickle of black talent into football had almost

died out. In a society under the pressure of persistent discrimination,

which still generally regarded black people as, at best, intriguing curiosities,

the widescale acceptance of black footballers was still some way off.

The boom in Commonwealth immigration had certainly not made much impact

in Leeds by the time Gerry Francis arrived from Johannesburg in 1957.

'As Leeds United's first ever black player, Francis' place in the social

and cultural history of the club is assured, but his fitful displays on

the right wing are far less likely to be remembered. There is no evidence

that his career was hampered by prejudice. In common with most other Leeds

players, his spell at Elland Road was one long depressing cycle of dazzling

display followed by stagnation, dropping down into the reserves, improvement

and recall, before the sequence started all over again.'

Phil Vasili: 'Soon after Steve Mokone (who played for Coventry and Cardiff

in the Fifties), Gerry Francis became the second Black South African to

be signed by a British club. Born in Johannesburg on 6 December 1933 of

African and Asian parents, Gerry Francis was signed by First-Division

Leeds United from City and Suburban FC in the summer of 1957. He played

fifty games - usually on the wing - over four seasons, scoring nine goals.

In 1961 he was transferred to York City of the Fourth Division, where

he played sixteen games and scored four goals.

back to top

'It was not until 10 October 1959 that Francis made his debut for Leeds

against Everton, becoming the first Black South African to play in the

First Division and the first man of colour to play for the Elland Road

club. However, United were relegated at the end of the season. Described

as a "shoe repairer", the diminutive Francis did not show a

clean set of heels to his opposing full-back enough to earn himself a

regular first team place. He laboured through four undistinguished seasons

at a depressed club which felt sorry for itself, with few personal highlights

to lift his confidence. In October 1961 he signed for York City and then,

in the close season of 1962, joined Southern League Tonbridge. On retirement

from football, Francis initially became a postman, eventually emigrating

to Canada where he still lives. In the summer of 1997, along with Steve

Mokone, he returned to Britain for a celebratory evening dedicated to

the Pioneers of Black British Football, held in Birmingham.'

Despite his shyness and lack of confidence, Albert Johanneson impressed

the newly appointed United manager, Don Revie. It only required a couple

of training sessions for Revie to make his mind up and Johanneson became

his first signing for the club. This was despite the South African struggling

to cope with the alien conditions of a British winter, as he recalled

later: 'One Monday in Leeds I did not want to get out of bed because it

was so cold. I had a trial and they took me off because it was too cold.

I thought I was finished.'

Coming from an environment of rigid apartheid, Johanneson was shocked

by the expectation that he would share the communal bath with his white

colleagues. His new team mates left him in no doubt, stripping him and

hurling him into the water. He was similarly apprehensive when a white

apprentice was detailed to clean his boots.

Rick Broadbent: 'When an Everton player called him a "black bastard"

during a game, Johanneson complained to Revie. His manager's response

was, "Well, call him a white bastard back." For a personality

plagued by self doubt, such a ready dismissal of the racism that was common

in the game at the time was hardly helpful.'

Phil Vasili: 'Within days of signing for Leeds ... Albert "Hurry,

Hurry" Johanneson was making his Division Two debut ... and immediately

made an impact.

'Johanneson was "making good" after arriving at Elland Road

from Johannesburg in 1961 with his modest belongings packed in a suitcase.

He was given a trial with United on the recommendation of a South African

schoolmaster who had spent hour upon hour teaching him the skills of the

game until he could control a tennis ball with his bare feet almost as

easily as he could walk ... [He] impressed United sufficiently to be taken

on as a full time professional after making a fine debut against Swansea

Town in April 1961 when he made his mark almost immediately, measuring

a centre perfectly for Jack Charlton to ram home a header.

'His superior skills on the training ground 'demoralised' the other players

who were consistently "run into the ground" by the South African.'

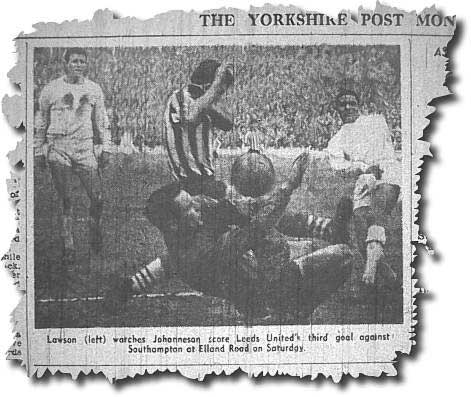

Johanneson made his first team debut at outside-left in a 2-2 draw at

home to Swansea Town on April 8 1961, creating one of Jack

Charlton's two goals with a perfect cross. It was later reported that

'As his teammates ran towards him to congratulate him, he froze.' Paul

Eubanks, a Leeds teacher who has fought steadfastly to preserve Johanneson's

memory: 'Albert came from South Africa where it only meant one thing when

white men chased after a black man. I've spoken to people who knew him

in the 60s and they say he had a mental block at that point ... He'd play

at grounds and there'd be the monkey noises and the bananas, but he was

suddenly allowed to go places he hadn't been and talk to people he couldn't

even look at before.'

Eric Stanger wrote in the Yorkshire Post of Johanneson's debut

that he 'got off to a most promising start. He has a good left foot, a

great body swerve and looked very good when he came infield.'

He retained his place for the remaining four matches, including the 7-0

thrashing of Lincoln City, and played the first seven games of the following

campaign, though they yielded only five points. On a couple of occasions,

Francis was also in the line up, on the opposite flank, exciting media

interest, but by October the older man had moved on to York City. Johanneson

lost his place to the even younger John Hawksby.

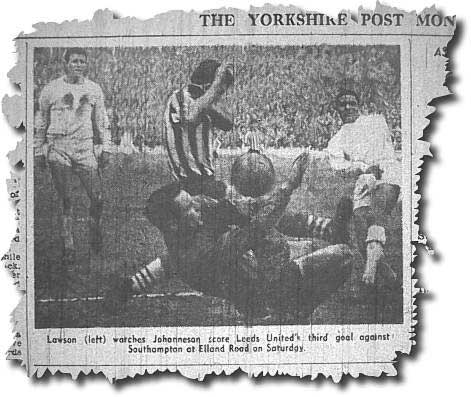

He returned to the team in January to score his first United goal, a

penalty in an FA Cup defeat at home to Rotherham, and figured again a

fortnight later at home to Newcastle in the league. He then missed out

until 14 April when he was recalled for a trip to Walsall with Leeds struggling

to avoid relegation. He scored to help United earn a 1-1 draw which lifted

them out of the drop zone. Johanneson was a first-eam regular from that

point on.

By now, former Everton midfielder Bobby Collins

had arrived to lead United's fight against the drop, and the Scot used

his experience to bring the best out of the pacy winger. As Collins said,

'Albert could fly and I could put the ball on the spot for him. When he

was in his stride there weren't many who could catch him.'

back to top

Leeds travelled to Newcastle on the final day still requiring a win to

confirm safety. Brilliant combination work between Collins and Johanneson

secured a superb 3-0 victory. Andrew Mourant described it as 'their best

performance of the season ... Playing in a stiff wind and on an unyielding

pitch, Revie's team struck rare form. Bobby Collins, Willie Bell, playing

out of position as an inside-forward, and Albert Johanneson were key figures

in a performance of collective discipline. Johanneson's first half goal

on 37 minutes, a header from Johanneson's cross by McAdams after 65 minutes and an own goal by Newcastle

right-back Bobby Keith ten minutes later, gave Revie deliverance.'

Johanneson's cross by McAdams after 65 minutes and an own goal by Newcastle

right-back Bobby Keith ten minutes later, gave Revie deliverance.'

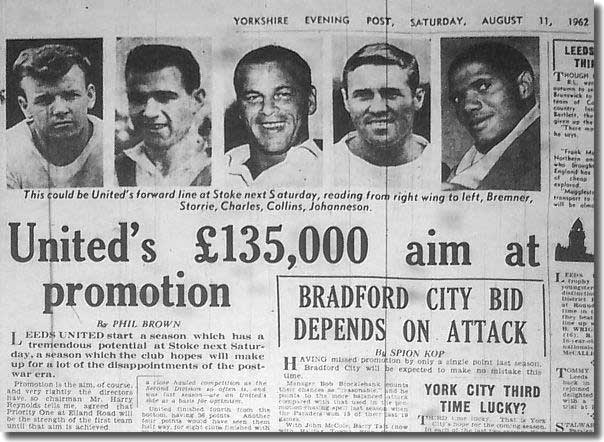

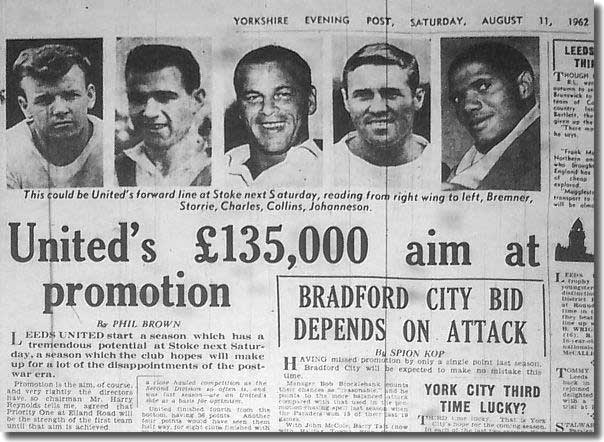

The manager hoped to take United to promotion in 1962/63

and in an attempt to bolster their chances he signed John

Charles and Jim Storrie to pep up the forward

line. The Charles gamble ended in failure and the Welshman was soon on

his way back to Italy, but Johanneson rose to new heights, along with

the other youngsters who were given their heads that season.

After the opening game of the season against Stoke, Phil Brown wrote

in the Evening Post, 'Johanneson, a fast and dextrous ball player

...looked and often played like some rising star from Brazil. Before long

Asprey was casting quick suspicious glances over his shoulder - even when

the ball was elsewhere - as though Johanneson were some angry wasp, not

to be trusted.'

During the midweek clash with Rotherham it was Johanneson, rather than

Charles, who was entrusted with the penalty that Leeds were awarded. He

slotted it away coolly, though Rotherham won the game, 4-3. Eric Stanger

remarked that 'the brightest features were the hard working displays of

Collins and Johanneson.'

The winger missed another penalty in the following game, at home to Sunderland,

but Leeds secured a 1-0 win, with Billy Bremner scoring from a Johanneson

cross. Richard Ulyatt in the Yorkshire Post: 'The policy behind

allowing Johanneson to take the penalty seems another example of the confused,

or involved, thinking to which United are prone. True, Johanneson scored

from a penalty earlier in the week. But he is the least experienced member

of the team, indeed, he is not yet established in it and his form on Saturday

raised doubts as to whether he will improve on early promise.'

Phil Brown was more positive in the Evening Post: 'On the brighter

side of things there is the great advance of 21-year-old Albert Johanneson.

Albert is the first to admit he has something to learn yet, but he is

learning, and he has plenty of natural gifts to help him. When did you

last see a winger stop in full stride so shatteringly?'

He was fast becoming a key player and scored twice when United beat Chelsea

after going down to ten men on 15 September. The first was a beauty, according

to Phil Brown: 'Charles brought the ball up from halfway, Peyton swept

in to join him going left and passed out to the left winger. He dodged

round three desperate tacklers like an eel and coming up to his near post

popped the ball gently past Bonetti.'

W Ian Guild in the Yorkshire Post: 'The man who brought the crowd

to their feet was Johanneson, scorer of both goals, and the first United

player I have seen applauded by his team mates as he trotted to the dressing

room.'

Johanneson's total of 14 goals in league and Cup was the best ever by

a United winger and was bettered only by Jim Storrie that season.

back to top

He went even better in 1963/64,

top scoring with 15, as United captured the Second Division title.

The Times praised him thus in November after a draw with promotion

rivals Charlton: 'He showed all the flair and loose limbed speed for the

game ... High of action, he moved with supple grace, his feet scarcely

touching the ground as if it were hot coal.'

Johnny Giles: 'At that time I believed Johanneson would become one of

the game's outstanding personalities. He scored one of the finest goals

I have ever seen towards the end of that season in Leeds' vital Easter

fixture against Newcastle at Elland Road ... an unbelievable effort which

left the Newcastle defenders spellbound. Albert was surrounded by three

Newcastle players as he brought down a long pass through the middle and

it looked certain that he would be forced away from goal. Yet in the space

of no more than five yards he sidestepped them all, one after another,

and then coolly slipped the ball past the goalkeeper as he came off his

line!'

Rob Bagchi and Paul Rogerson: 'It was unfortunate that Leeds should lose Jim Storrie to injury after only nine

games of the season, since his absence tended to make their game one-dimensional.

They became over reliant on Albert Johanneson, who had his finest ever

season, even with all the physical and racial abuse meted out by Neanderthal

full-backs terrified by his turn of foot. Don

Weston deputised for Storrie for most of the first half of the season

but, like Johanneson, his game was based on speed. He matched Albert's

strike rate, but these two sprinters, often playing at breakneck pace,

at the very edge of their capability, were as liable to make elementary

blunders as torment the opposing team. Thirteen goals apiece were perfectly

satisfactory for support players but hardly compensated for the loss of

Storrie's productiveness. Similarly, their styles necessitated a higher

tempo; they would receive the ball, dribble with it, pass, cross or shoot

it in a matter of seconds, whereas Storrie had the strength and canniness

to lead the line in the conventional way, playing with his back to goal,

holding the ball up and inviting the midfield to influence the shape of

the attack.'

unfortunate that Leeds should lose Jim Storrie to injury after only nine

games of the season, since his absence tended to make their game one-dimensional.

They became over reliant on Albert Johanneson, who had his finest ever

season, even with all the physical and racial abuse meted out by Neanderthal

full-backs terrified by his turn of foot. Don

Weston deputised for Storrie for most of the first half of the season

but, like Johanneson, his game was based on speed. He matched Albert's

strike rate, but these two sprinters, often playing at breakneck pace,

at the very edge of their capability, were as liable to make elementary

blunders as torment the opposing team. Thirteen goals apiece were perfectly

satisfactory for support players but hardly compensated for the loss of

Storrie's productiveness. Similarly, their styles necessitated a higher

tempo; they would receive the ball, dribble with it, pass, cross or shoot

it in a matter of seconds, whereas Storrie had the strength and canniness

to lead the line in the conventional way, playing with his back to goal,

holding the ball up and inviting the midfield to influence the shape of

the attack.'

He remained the fans' favourite, as reported by Bill Mallinson in the

Evening Post: 'Johanneson received a special encouraging cheer

whenever United tried to get him into action ... If he showed the same

front of goal steadiness more often, his already considerable fan club

at Elland Road would rapidly grow ... Johanneson has the speed and ability

to perplex the majority of opposing full-backs, and he has been in Second

Division football long enough for United to hope that the time is not

far off when he will add the front-of-goal temperament which is all he

needs to become as deadly a menace as Southampton's international right

wingman Terry Paine ... From the throw in United worked the ball out to

Johanneson, who moved infield with a splendid dribble. His way was barred

by three Argyle defenders, but he foxed the lot of them with a clever

change of direction before driving a beautiful right foot shot just inside

McLaren's right hand post with the goalkeeper groping helplessly. It was

a splendid goal, and no wonder the United supporters began to chant "Albert!

Albert!"'

Following United's title triumph, Johanneson spent the summer back in

South Africa for the first time in three years. Refreshed by the break,

he rose to the challenge of top-flight football in 1964/65;

he was outstanding as Leeds ended the season runners-up in league and

Cup.

He got the club's first goal of the campaign, equalising against Aston

Villa on the opening day before Jack Charlton snatched the winner. Phil

Brown claimed in the Yorkshire Evening Post afterwards that Johanneson

'settled down to his game probably faster than anybody on the field. He

was tormenting Villa with his tricky running very quickly, and took his

goal coolly from a fiery rebound of a vicious drive by Weston off goalkeeper

Sidebottom.'

The Black Flash went from strength to strength, stringing together a

series of outstanding displays. The Yorkshire Post noted that he

'has so grown in confidence these days that he is now racing into the

gaps and calling for the ball'.

back to top

The FA Cup semi-final against Manchester

United saw Nobby Stiles kick Johanneson out of the game, hammering

him viciously early on and then pressing home his advantage thereafter.

The damage kept the winger out of the replay.

Nevertheless, he had enjoyed a wonderful season, with The Times

describing him as 'the colourful, popular, Johanneson from Johannesburg,

whose gazelle-like speed down the wing draws the crowds down the terraces,

an exciting player in the mould of some dusky Brazilian'.

The Wembley Cup final against Liverpool

should have been the opportunity to showcase his talents, but it was a

game to forget for the South African, though he would never be allowed

to consign it to memory. He was the first black player to feature in the

Cup final, but just as historically renowned as the potential match winner

who froze on the biggest stage of all, a virtual passenger as United struggled

to make any sort of mark, losing 2-1. He had hurt an ankle in a draw

at Birmingham earlier in the week but his problems seemed to be more

mental than physical that day.

Phil Vasili: 'Fellow players recognised that Albert came in for special

treatment. Even Jack Charlton, a prize graduate of the hit 'em and knock

'em high school of defending, remembers Albert being assaulted. "[He]

was fouled with a tackle which would have enraged anyone." A friend

of Albert's, Guy McKenzie, reflected in 1995 on how his late friend became

a target for the hard men in opposition defences; and how Jack Charlton

and Billy Bremner took it upon themselves to become Johanneson's on field

minders. The roughing up of creative players by defensive destroyers was

a common practice in the 60s, when the bruisers were allowed to play with

a level of violence that Charlton Heston and the National Rifle Association

would have been proud of. Then, the two-footed lunge from behind was a

legitimate weapon in a defender's armoury. With Albert usually the only

black man on the field,  and with a manager usually insensitive to the

issue of racial abuse, such battles were often faced and felt alone. Back

over the other side of the white line - in the changing room, front room

or high street - there were little or no support structures available

to galvanise a battered confidence. To play well steels the soul against

such abuse, to play badly weakens that protection.'

and with a manager usually insensitive to the

issue of racial abuse, such battles were often faced and felt alone. Back

over the other side of the white line - in the changing room, front room

or high street - there were little or no support structures available

to galvanise a battered confidence. To play well steels the soul against

such abuse, to play badly weakens that protection.'

Johanneson was never the same player from that point on. He returned

to his native South Africa for a summer break to recharge his batteries,

but then missed most of the following

campaign with injuries, first to the ankle and then thigh. He was

supplanted by Mike O'Grady, newly signed from

Huddersfield.

He did return in time to play in both legs of the Fairs Cup semi-final

against Real Zaragoza. After 15 minutes of the first leg in Spain, Johanneson

was left with only the goalkeeper to beat, but pulled his shot wide. He

did get on the score sheet in the second leg at Elland Road, opening the

scoring from close range in the 22nd minute from a headed pass from Jack

Charlton. He later repaid the favour, creating a goal for Charlton after

retrieving a ball that had looked certain to go out of play. He missed

the replay through injury as United were hammered 3-1.

By now he was regularly handicapped by leg injuries. The game's hard

men had sussed out that he was intimidated by heavy challenges and rarely

spared the rod. United general manager Alan Roberts: 'I remember what

happened to him against Tottenham at Elland Road. Cyril Knowles was marking

him. Albert was very quick and very skilful but he was a timid sort of

a man. Quiet, meek, unassuming. Well, Cyril gave him a hell of a whack

in the first five minutes and it put him right off his game.'

The 1966/67 season was ruined

for Johanneson by niggling injuries. He missed the opening game against

Tottenham and though he was back for the following match, against West

Bromwich Albion, Eric Stanger commented, 'The return of Johanneson was

scarcely a triumph.' He laid on a goal in the defeat of Manchester United,

but was then dropped.

Johanneson drifted in and out of contention thereafter, though he managed

seven goals in 22 league games. His form veered haphazardly from the sublime

to the ridiculous. Terry Lofthouse in the Yorkshire Post after

the League Cup victory over Newcastle in September: 'Johanneson certainly

had more fire in his play. But he still has that frustrating tendency

to cross the ball too close to the keeper instead of pulling it back to

give his forwards a chance.' Eric Stanger later described him as 'irritatingly

erratic'.

Nevertheless, he managed a hat trick in the 5-1 rout of DWS Amsterdam

in the Fairs Cup after scoring one of United's three in Amsterdam.  Stanger:

'Johanneson got the first two goals ... with fine artistry. First he crowned

a neat move between Hunter and Madeley and went through the Dutch defence

like a dancing master. Then he was in the right spot at the right time

to take Greenhoff's through pass and score with calculated deliberation.

The crowd rose to him and booed when the South African was denied his

chance of a hat trick by not being allowed to take a penalty five minutes

before half time ... A fifth goal did come when Johanneson's shot hit

Cornwall's leg on the way and the ball was diverted past Schrijvers.'

Stanger:

'Johanneson got the first two goals ... with fine artistry. First he crowned

a neat move between Hunter and Madeley and went through the Dutch defence

like a dancing master. Then he was in the right spot at the right time

to take Greenhoff's through pass and score with calculated deliberation.

The crowd rose to him and booed when the South African was denied his

chance of a hat trick by not being allowed to take a penalty five minutes

before half time ... A fifth goal did come when Johanneson's shot hit

Cornwall's leg on the way and the ball was diverted past Schrijvers.'

back to top

He was limited to 8 starts and one league appearance off the bench in

1967/68, though again he managed

a European hat trick in the 7-0 thrashing of Spora Luxembourg. He remained

as popular as ever with the United fans; The Guardian's Paul Fitzpatrick

noted in his report of the Fairs Cup-tie with Partizan Belgrade, 'Johanneson,

a firm favourite with the Leeds supporters, was given a cheer when he

took the field at the start of the second half.' Similarly, after the

7-0 defeat of Chelsea in October, the Evening Post's Phil Brown

remarked, 'Johanneson sent his fans almost delirious by nimbly notching

the first with his head (an event in itself for Albert) in five minutes.'

He damaged knee ligaments shortly afterwards, though he returned for

some more magic moments. After he netted two in the 3-1 defeat of Burnley

in January 1968, Richard Ulyatt offered this praise in the Yorkshire

Post: 'Leeds' greatest source of satisfaction must have come from

the display of the wingers, O'Grady and Johanneson. As those of us who

know who have watched the team closely, Johanneson has improved greatly

in the last two years in judgement and confidence. Allied to his great

skill, those two assets now make him one of the best left wingers in the

game. His two second half goals were the result of opportunism and accuracy.'

Despite that praise, Eddie Gray's emergence had pushed Johanneson down

the pecking order, and with Mike O'Grady monopolising the right flank

Johanneson managed a solitary league appearance during the

championship campaign that followed. That was when he came off the

bench during the 2-0 defeat of Stoke City in August, though he netted

one of the goals. He also scored in both of his games in domestic Cup

competitions, in the FA Cup third round defeat to Sheffield  Wednesday

and again in the League Cup victory against Bristol City. His goal against

Wednesday was a memorable effort, hammered through a packed area after

a poor punch by keeper Springett.

Wednesday

and again in the League Cup victory against Bristol City. His goal against

Wednesday was a memorable effort, hammered through a packed area after

a poor punch by keeper Springett.

United put Johanneson on the transfer list in June 1969, promising to

release him if anyone met the modest asking price. The club agreed terms

with Bury, but the winger turned the move down. There were rumours that

he would join Brighton, managed by former Leeds team mate Freddie Goodwin,

but nothing came of the speculation.

The 1969/70 season was to be

Johanneson's swansong for United and he was limited to just two games

in the final few weeks; in the second he was completely overshadowed by

the man who had made the No 11 shirt his own, Eddie Gray. The Scot scored

two of the most wonderful goals in United's history, the second after

jinking his way across a packed Burnley area to score a wonderful individual

goal. It was symbolic that Johanneson could only watch in awe, writhing

in pain after a heavy tackle, as the young pretender demonstrated the

sort of confidence that had sapped from the South African's own play.

Johanneson was transfer-listed again at the beginning of May 1970. This

time he did secure a deal with Fourth Division York City coming in for

him. In his nine years at Elland Road, he had scored 76 goals in 200 appearances

in all competitions.

Johanneson demonstrated he still had something to offer, though he continued

to be dogged by injuries and fitness problems. He was limited to 26 League

games, scoring three times as the Minstermen won promotion. A key factor

was the 26 goals scored by centre-forward Paul Aimson, who owed much to

Johanneson's service from the flank.

York also enjoyed a decent FA Cup run, reaching the fourth round before

going out after a replay to First Division Southampton. With three minutes

remaining in the first game at Bootham Crescent, they were 3-1 down but

then scored twice to earn a 3-3 draw and came close to doing the same

in the replay at the Dell.

With seven minutes to go, Johanneson scored to make it 3-2, calmly chipping

the ball over two Southampton men on the line, but the Saints held out

for the win. According to Norman Fox in The Times, Johanneson's

'designs were often brought to unglamorous endings but at worst he was

more entertaining than much of the football'.

back to top

Sadly

that was one of the final moments of glory for the Black Flash. Injury

prevented him kicking a ball in anger at all in 1971/72 as York City avoided

relegation on goal average alone. Johanneson was made available on a free

transfer in May 1972, but when there were no takers, he decided to retire

as his injury problems persisted.

Sadly

that was one of the final moments of glory for the Black Flash. Injury

prevented him kicking a ball in anger at all in 1971/72 as York City avoided

relegation on goal average alone. Johanneson was made available on a free

transfer in May 1972, but when there were no takers, he decided to retire

as his injury problems persisted.

With his playing days over and time weighing heavy on his hands, Johanneson

was preoccupied by his fall from grace. He drifted into alcoholism and

his wife and two children left him to live in America. He admitted that

he had driven them away: 'I was a bastard, I couldn't handle the game.

I've got nothing.'

Many of his former colleagues tried to rescue him from his decline. Peter

Lorimer: 'We tried to help him. We wanted to get him to join the [former

players'] association but it was no good. Albert would just go missing.'

Eddie Gray: 'One of the first signs of his reliance on drink had come

in a match against Stoke in the 1966/67 season. Don Revie always kept

a bottle of whisky in the dressing room for Bobby Collins, who had long

been in the habit of taking a small swig of the hard stuff before a match

as a kind of psychological performance booster. Albert, who was substituted

at half time in that match and remained in the dressing room when we went

out for the second half, got his hands on it. By the time we came back

into the dressing room after the match, he had drunk the rest of the bottle

and was comatose.

'When I was Leeds manager, he would sometimes come to visit me at the

ground. He would tell me that he wanted to start training again, but could

not afford to buy any boots. I would give him all the equipment he needed,

but I always knew that he really wanted it so that he could sell it and

use the money to buy drink.

'It was not difficult to be moved by the story of Albert's decline. One

day when Linda came to pick me up at the ground and we spotted Albert

by the main entrance, we gave him a lift into town. During the journey,

Albert talked about all the things that had gone wrong in his life. I'd

heard it so many times that I had become emotionally immune to it, but

it had a big effect on Linda. By the time Albert left us, tears were rolling

down her cheeks like a waterfall.'

Phil Vasili: 'Journalist Luke Alfred, visiting a yellowing, decrepit

and deprived Johanneson in 1992, was alarmed to find a man who still believed

better times were ahead. He even had an agent, David Robinson, who promised

to carve and fashion that bright future. Unfortunately agent Robinson's

greatest ability seemed to be in convincing Albert that what came out

of his - Robinson's - mouth was not bullshit but realisable hope. Attempts

were made to help Albert, most notably by former colleague Peter Lorimer,

but it was too late. Robinson's promise of a brighter dawn never broke.

But Albert's spirit did.'

His alcoholism left him in dire straits; he tried to get into St George's

Crypt one night but was turned away and ended up sleeping in a railway

station. A Leeds supporter who worked at the Griffin Hotel recognised

him and used to let him sleep on a bench in the TV lounge of the hotel.

He later moved in with his brother, Trevor (who suffered from similar

problems).

In 1992, his nephew, Hepburn Graham Junior, an actor, met up with Johanneson

while he was appearing at the West Yorkshire Playhouse. Hepburn was apparently

horrified at Johanneson's physical and mental condition and persuaded

him to book into a detoxification clinic in Middlesex.

Tragically, there was to be no recovery and Johanneson was found dead

in a tiny council flat in a tower block in Gledhow in September 1995,

aged just 53. It was thought that a bout of meningitis had been the cause.

back to top

He

was buried on 9 October at Lawnswood Cemetery in Leeds. More than 100

mourners attended the funeral, including his daughters and a number of

former team mates. But that wasn't the end of the story.

He

was buried on 9 October at Lawnswood Cemetery in Leeds. More than 100

mourners attended the funeral, including his daughters and a number of

former team mates. But that wasn't the end of the story.

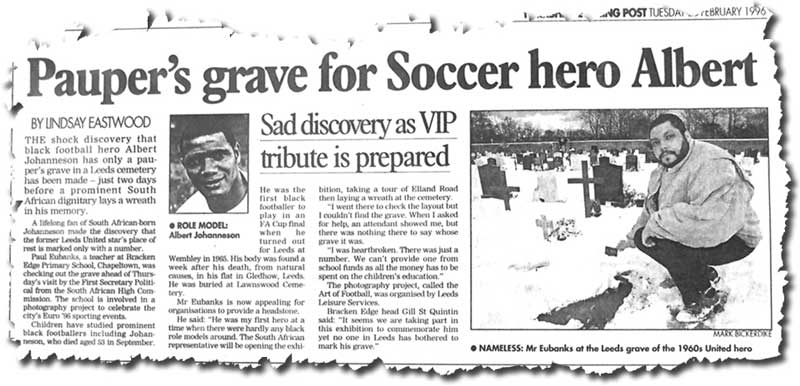

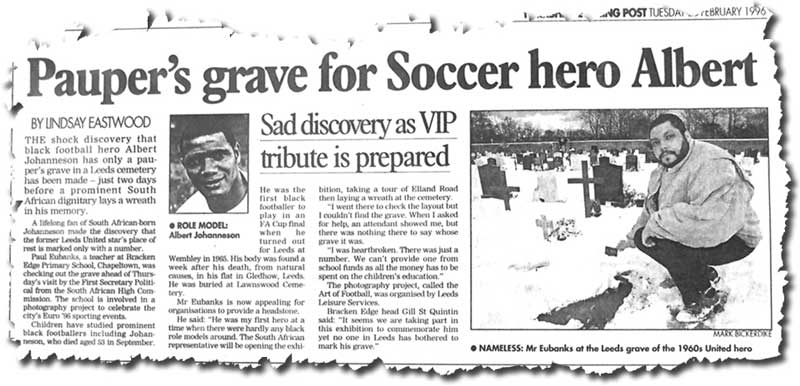

A few months later, Paul Eubanks, a teacher at Bracken Edge Primary School,

Chapeltown, was working with children on a photography project to celebrate

the city's Euro 96 sporting events. Bracken Edge was just one of a handful

of schools working on the project, called the Art of Football, inspired

by Eubanks' suggestion of paying a tribute to Johanneson. The event was

an incredible success and Eubanks persuaded the FA to allow the FA Cup

to be used in the display. He also arranged for the First Secretary Political

from the South African High Commission, Beston Banda, to open the exhibition

and lay a wreath at Johanneson's grave. Sheffield Wednesday forward Mark

Bright was also in attendance at the exhibition.

Eubanks was a lifelong fan of Johanneson, the admiration sparked by his

late father, Lionel George Eubanks, who died in 2008. Eubanks: 'He was

the reason for all this. He came from Jamaica in 1955 and within years

had found another love other than cricket - Leeds United. In 1965, when

I was seven, he took me to Elland Road to an Inter Cities Fairs Cup game

and it was there that I saw Albert for the very first time, an image that

stayed with me. After that I was a regular at games with my dad and what

you have to remember is that there were hardly any black supporters then,

and there were dad and I, "two black specks in a sea of white".

He was my first hero at a time when there were hardly any black role models

around.'

Eubanks attended Johanneson's funeral and has since been involved in

a number of documentaries about him and talked about him at a number of

anti-racism conferences held in Europe.

It was agreed that Banda would open the exhibition, take a tour of Elland

Road and lay a wreath on Johanneson's grave. Eubanks visited the cemetery

a few days before the visit to make sure all was in order, but couldn't

find the grave. Eubanks: 'When I asked for help, an attendant showed me,

but  there

was nothing there to say whose grave it was. I was heartbroken. There

was just a number.'

there

was nothing there to say whose grave it was. I was heartbroken. There

was just a number.'

The story was featured in the Yorkshire Evening Post. When Leeds

United chairman Leslie Silver heard the news, he paid for an emergency

wooden cross and plaque to be placed at the plot hours before Banda arrived.

Johanneson's daughter Alicia takes up the story: 'While my sister, Yvonne,

and I were in Leeds attending my father's funeral we arranged with Leeds

United to have the headstone that currently marks his grave made and inscribed

with the Maya Angelou poem, which we chose to put on it knowing from whence

our father came and what he achieved in his short football playing career.

The club paid for the headstone to be made, and ensured that it was placed

on the grave once completed.'

It was a sad way for any man to end his life, in absolute keeping with

the tragic denouement that Johanneson experienced in his latter years,

but at least there is a fitting monument to his memory.

Far better to remember Albert Johanneson for all the good times, to recall

him for the glorious memories that he provided for all who followed Leeds

United in the 1960s: the Black Flash was a spectacular and exceptional

talent in a team for whom the word 'dour' could easily have been coined.

back to top

Rick

Broadbent from Looking For Eric: 'In a quieter part of West Yorkshire

is Lawnswood Cemetery ... The man in the office is incongruously cheerful

and wears a bright orange tie ... "You want to see Albert ... We

get quite a few people wanting to see him" ... He leaves me in peace

and I kneel before the mottled grey monument to Albert Johanneson. There

is part of a poem by the writer, actress and civil rights activist Maya

Angelou inscribed in black on the stone. It is a poignant and apt epitaph:

Rick

Broadbent from Looking For Eric: 'In a quieter part of West Yorkshire

is Lawnswood Cemetery ... The man in the office is incongruously cheerful

and wears a bright orange tie ... "You want to see Albert ... We

get quite a few people wanting to see him" ... He leaves me in peace

and I kneel before the mottled grey monument to Albert Johanneson. There

is part of a poem by the writer, actress and civil rights activist Maya

Angelou inscribed in black on the stone. It is a poignant and apt epitaph: a

mender of shoes in Johannesburg. And though he was lifted from that by

an ability to put boot to ball, the upbringing crippled his self esteem.

His social stiffness was more than shyness. His marriage failed ... From

time to time, when the Leeds United team he graced held reunions, people

tried to invite him. When he could be found, he might promise to turn

up, but those were promises diluted by alcohol and methylated spirits.

a

mender of shoes in Johannesburg. And though he was lifted from that by

an ability to put boot to ball, the upbringing crippled his self esteem.

His social stiffness was more than shyness. His marriage failed ... From

time to time, when the Leeds United team he graced held reunions, people

tried to invite him. When he could be found, he might promise to turn

up, but those were promises diluted by alcohol and methylated spirits. Francis

made his first team debut. He struggled to hold down a place, but he was

given an extended run in 1960/61 and his presence at Elland Road made

it easier for Johanneson to settle into this new, alien world.

Francis

made his first team debut. He struggled to hold down a place, but he was

given an extended run in 1960/61 and his presence at Elland Road made

it easier for Johanneson to settle into this new, alien world. Johanneson's cross by McAdams after 65 minutes and an own goal by Newcastle

right-back Bobby Keith ten minutes later, gave Revie deliverance.'

Johanneson's cross by McAdams after 65 minutes and an own goal by Newcastle

right-back Bobby Keith ten minutes later, gave Revie deliverance.' unfortunate that Leeds should lose Jim Storrie to injury after only nine

games of the season, since his absence tended to make their game one-dimensional.

They became over reliant on Albert Johanneson, who had his finest ever

season, even with all the physical and racial abuse meted out by Neanderthal

full-backs terrified by his turn of foot. Don

Weston deputised for Storrie for most of the first half of the season

but, like Johanneson, his game was based on speed. He matched Albert's

strike rate, but these two sprinters, often playing at breakneck pace,

at the very edge of their capability, were as liable to make elementary

blunders as torment the opposing team. Thirteen goals apiece were perfectly

satisfactory for support players but hardly compensated for the loss of

Storrie's productiveness. Similarly, their styles necessitated a higher

tempo; they would receive the ball, dribble with it, pass, cross or shoot

it in a matter of seconds, whereas Storrie had the strength and canniness

to lead the line in the conventional way, playing with his back to goal,

holding the ball up and inviting the midfield to influence the shape of

the attack.'

unfortunate that Leeds should lose Jim Storrie to injury after only nine

games of the season, since his absence tended to make their game one-dimensional.

They became over reliant on Albert Johanneson, who had his finest ever

season, even with all the physical and racial abuse meted out by Neanderthal

full-backs terrified by his turn of foot. Don

Weston deputised for Storrie for most of the first half of the season

but, like Johanneson, his game was based on speed. He matched Albert's

strike rate, but these two sprinters, often playing at breakneck pace,

at the very edge of their capability, were as liable to make elementary

blunders as torment the opposing team. Thirteen goals apiece were perfectly

satisfactory for support players but hardly compensated for the loss of

Storrie's productiveness. Similarly, their styles necessitated a higher

tempo; they would receive the ball, dribble with it, pass, cross or shoot

it in a matter of seconds, whereas Storrie had the strength and canniness

to lead the line in the conventional way, playing with his back to goal,

holding the ball up and inviting the midfield to influence the shape of

the attack.' and with a manager usually insensitive to the

issue of racial abuse, such battles were often faced and felt alone. Back

over the other side of the white line - in the changing room, front room

or high street - there were little or no support structures available

to galvanise a battered confidence. To play well steels the soul against

such abuse, to play badly weakens that protection.'

and with a manager usually insensitive to the

issue of racial abuse, such battles were often faced and felt alone. Back

over the other side of the white line - in the changing room, front room

or high street - there were little or no support structures available

to galvanise a battered confidence. To play well steels the soul against

such abuse, to play badly weakens that protection.' Stanger:

'Johanneson got the first two goals ... with fine artistry. First he crowned

a neat move between Hunter and Madeley and went through the Dutch defence

like a dancing master. Then he was in the right spot at the right time

to take Greenhoff's through pass and score with calculated deliberation.

The crowd rose to him and booed when the South African was denied his

chance of a hat trick by not being allowed to take a penalty five minutes

before half time ... A fifth goal did come when Johanneson's shot hit

Cornwall's leg on the way and the ball was diverted past Schrijvers.'

Stanger:

'Johanneson got the first two goals ... with fine artistry. First he crowned

a neat move between Hunter and Madeley and went through the Dutch defence

like a dancing master. Then he was in the right spot at the right time

to take Greenhoff's through pass and score with calculated deliberation.

The crowd rose to him and booed when the South African was denied his

chance of a hat trick by not being allowed to take a penalty five minutes

before half time ... A fifth goal did come when Johanneson's shot hit

Cornwall's leg on the way and the ball was diverted past Schrijvers.' Wednesday

and again in the League Cup victory against Bristol City. His goal against

Wednesday was a memorable effort, hammered through a packed area after

a poor punch by keeper Springett.

Wednesday

and again in the League Cup victory against Bristol City. His goal against

Wednesday was a memorable effort, hammered through a packed area after

a poor punch by keeper Springett. Sadly

that was one of the final moments of glory for the Black Flash. Injury

prevented him kicking a ball in anger at all in 1971/72 as York City avoided

relegation on goal average alone. Johanneson was made available on a free

transfer in May 1972, but when there were no takers, he decided to retire

as his injury problems persisted.

Sadly

that was one of the final moments of glory for the Black Flash. Injury

prevented him kicking a ball in anger at all in 1971/72 as York City avoided

relegation on goal average alone. Johanneson was made available on a free

transfer in May 1972, but when there were no takers, he decided to retire

as his injury problems persisted. He

was buried on 9 October at Lawnswood Cemetery in Leeds. More than 100

mourners attended the funeral, including his daughters and a number of

former team mates. But that wasn't the end of the story.

He

was buried on 9 October at Lawnswood Cemetery in Leeds. More than 100

mourners attended the funeral, including his daughters and a number of

former team mates. But that wasn't the end of the story. there

was nothing there to say whose grave it was. I was heartbroken. There

was just a number.'

there

was nothing there to say whose grave it was. I was heartbroken. There

was just a number.'