Relegation

is never a pleasant experience for anybody, but Leeds United manager Jack

Taylor found it particularly hard in 1960

when, within a year of him taking over at Elland Road, the club lost their

First Division status. He felt let down by the players and decided that

drastic action was called for if the club were to recover their top flight

status quickly.

Relegation

is never a pleasant experience for anybody, but Leeds United manager Jack

Taylor found it particularly hard in 1960

when, within a year of him taking over at Elland Road, the club lost their

First Division status. He felt let down by the players and decided that

drastic action was called for if the club were to recover their top flight

status quickly.

The youth development and scouting policy, which Taylor's predecessor

Bill Lambton had instituted, was

starting to bear fruit, and by the start of the new season almost 50 local

youngsters had been signed as amateurs. However, it was to be a couple

of years before any of them were good enough for first team contention

and in the meantime Taylor needed experienced new blood to pep up his

ailing side.

The club's supporters had little reason for optimism after the tepid

performances of the previous year, but the manager set about rebuilding

the side. He signalled a dramatic clear out: exciting young winger Chris

Crowe left for Blackburn in March, raising a useful £25,000, but that

was only the start. Before the new season had kicked off, Taylor had also

presided over the departure of Wilbur Cush, Archie Gibson, George Meek

and Jack Overfield. The Crowe money had been used to buy Manchester United

defender Freddie Goodwin, who had steadied things at the back, but it

had proven far too little far too late.

Bagchi and Rogerson in The Unforgiven: 'By the beginning of the

1960/61 season, the bank's apprehension had become palpable, and Taylor's

request to recruit a few reliable, experienced professionals had understandably

been rejected by the Board. The other alternative, to generate funds by

selling one or two players, was also denied him. Of the relegated squad,

only three players had any significant monetary value: Billy Bremner,

who was just seventeen and had only recently broken into the first team;

John McCole, scorer of 22 goals that season but widely perceived as a

functional penalty-box predator and little else, and who, anyway, would

be vital to Leeds' attempt to achieve promotion; and Jack

Charlton, whose inconsistency on the park and militancy off it put

off a whole host of suitors. There was to be no quick fix.'

However, Jack Charlton, who was frankly unconvinced of the merits of

a future at Elland Road, did not look to be a permanent resident at Elland

Road. Leo McKinstry: 'By mid-1960, Jack was so fed up with Leeds that

he wanted out. Other clubs learned of his disillusion and showed an interest

in buying him. One of them was Liverpool, where Bill Shankly had just

taken over as manager. Now Liverpool were hardly a major force in British

soccer at the time. They had been languishing in the Second Division for

even longer than Leeds, having been relegated in 1954, and were short

of class and cash. Nor was Shankly regarded then as a titan of management.

But Shankly was consumed with a passionate ambition for his new club.

Having seen Jack in action many times, he thought he could mould him into

the centre half he needed at the heart of his defence. But Leeds, for

all Jack's faults, were reluctant to sell him. So the fee quoted to Shankly

was £20,000 plus, which the Liverpool board thought was too high. According

to his biographer, Stephen Kelly, "Shankly reckoned Charlton was

worth every penny" of this fee, but his views did not wash with the

directors, who would allow him no more than £18,000 to be spent on Jack.

The strict limit meant that the negotiations went nowhere and the potential

deal collapsed, much to the annoyance of Shankly and Jack.'

Taylor recognised that he needed reinforcements, and set about making

the best of the limited resources he was able to scrape together. He raided

the Scottish League, picking up two rugged defensive half-backs in Eric

Smith of Celtic and Queen's Park's Willie

Bell, along with St Mirren centre-back John McGugan, who had been

in the Scottish squad which toured Europe that summer, and Queen of the

South winger Tommy Murray. Taylor also bought former England winger Colin

Grainger, known as 'The Singing Winger' for his vocal stints in night

clubs, for £15,000 from Sunderland and travelled to Holland to sign Irish

forward Peter Fitzgerald from Sparta Rotterdam.

Taylor had also started building a formidable backroom team and in the

close season secured the services of two men who would be major influences

at Elland Road for years to come - Les Cocker and Syd Owen.

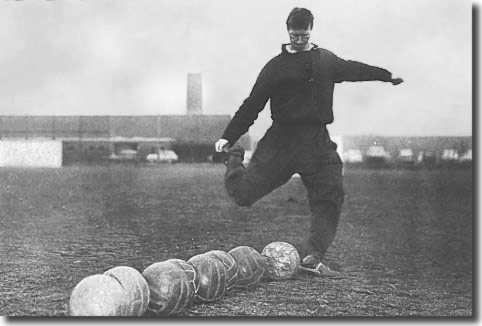

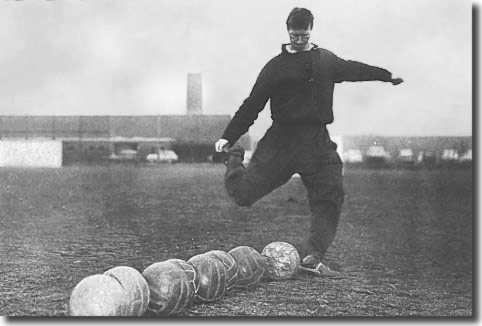

Bagchi and Rogerson: 'Les Cocker, the former Stockport County and Accrington

Stanley forward, had learnt, like so many of his contemporaries,  the

fundamentals of fitness in his wartime service with the Reconnaissance

Regiment in France after D-Day. He was temperamentally and professionally

qualified for the position of trainer. One of the first generation to

take the FA Coaching Certificate, he supplemented his tactical acumen

with exploratory studies in physiology and, more unusually, also dabbled

in the avant-garde sports sciences of kinesiology and biomechanics. He

had a stormy start with his new charges, who were contemptuous of his

dedication to their development, and had many a run-in with that self-styled

'one man awkward squad', Jack Charlton. Yet barely a year after joining

Leeds, he was summoned to Lancaster Gate and offered the prestigious job

of putting England squads through his revolutionary sequence of sadistic

drills, a position he was to occupy from 1966 right through to 1977.

the

fundamentals of fitness in his wartime service with the Reconnaissance

Regiment in France after D-Day. He was temperamentally and professionally

qualified for the position of trainer. One of the first generation to

take the FA Coaching Certificate, he supplemented his tactical acumen

with exploratory studies in physiology and, more unusually, also dabbled

in the avant-garde sports sciences of kinesiology and biomechanics. He

had a stormy start with his new charges, who were contemptuous of his

dedication to their development, and had many a run-in with that self-styled

'one man awkward squad', Jack Charlton. Yet barely a year after joining

Leeds, he was summoned to Lancaster Gate and offered the prestigious job

of putting England squads through his revolutionary sequence of sadistic

drills, a position he was to occupy from 1966 right through to 1977.

'For all his ructions with Charlton and the initial scepticism of the

other 'seen it all' seasoned pros, it was obvious that he was doing something

right. Fanatical and often abrasive, there was a touch of zealotry in

his soul. Indeed, in Brian Clough's characteristically brusque judgement

he was an 'aggressive, nasty little bugger'. 'Pots' and 'kettles' spring

to mind, but it was just these qualities that made Cocker so valuable.

His loyalty was unreserved and he brought structure, obstinacy and a certain

impassive relentlessness to his task, which was to become the cornerstone

of Leeds' physical authority.

back to top

'Cocker was rather more than the stereotypical 'sergeant-major' coach,

but there is little doubt that, more often than not, he played that role

to perfection. However, it was the more cerebral Owen who actually conducted

the technical sessions. A full England international, from 1941-46, he

had served in the RAF with distinction, on active service in Egypt, Austria

and Italy. Along with Cocker, he had joined Leeds from Luton Town in the

summer of 1960 to help Taylor's beleaguered team achieve promotion in

their first season back in the Second Division. Unlike Cocker, he had

a distinguished pedigree both as a player and a coach, and had actually,

briefly, been a manager himself. Having been sacked by Luton Town after

less than a year in charge, he was impatient in his desire to prove that

the progressive methods he had discovered at Lilleshall could be a success

as much on the field as on the blackboard. He, too, had problems imposing

his more modern philosophy on the conspicuously cynical Charlton, but

eventually, after one episode when Jack 'offered to take my coat off to

him', Charlton realised that he was rapidly beginning to unleash his dormant

potential under Owen's shrewd instruction.'

It was little short of a revolution and the Leeds supporters were shocked

by the sweeping changes after years of penny pinching by the board. Some

even began to half believe that Taylor could yet get their team winning

games.

The waters of optimism did not run deep, however. The first game of the

season saw Leeds United travel to face Liverpool at Anfield. Shankly's

up and coming charges had finished the previous season third in the table,

and were on an exciting march to better things - they provided a stern

challenge.

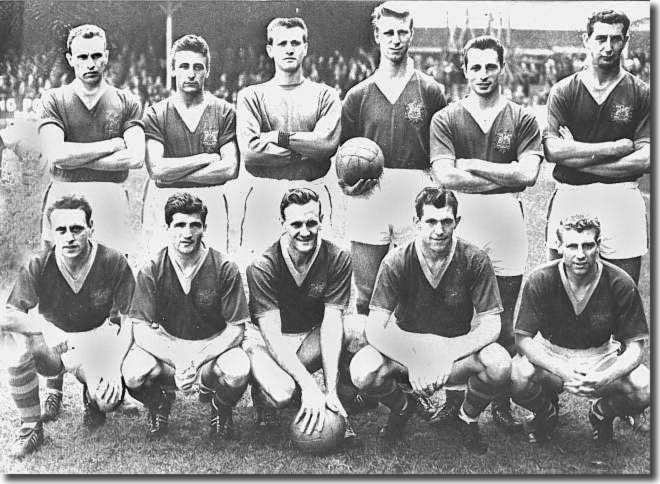

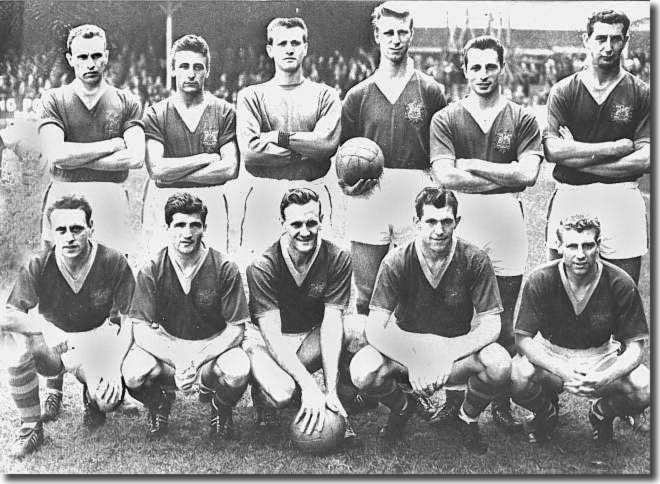

Taylor's team included Smith, Fitzgerald and Grainger, along with full

back Alf Jones, whom the manager had picked up from non-league Marine

in April. Charlton and  Goodwin

remained in the centre of defence, with Bremner and Revie in tandem on

the right and big John McCole leading the line.

Goodwin

remained in the centre of defence, with Bremner and Revie in tandem on

the right and big John McCole leading the line.

Over 43,000 fans flocked to Anfield to see Leeds well beaten and lucky

to depart with only a 2-0 defeat.

Taylor rang the changes for the second game, four days later at home

to Bristol Rovers, with Grenville Hair, South African winger Gerry Francis

and Irishman Noel Peyton coming in for Jimmy Ashall, Bremner and Fitzgerald,

but there was little improvement. Leeds drew 1-1 in front of just 11,330

fans, with McCole scoring the goal.

The next game, against Rotherham, brought further changes, with Scottish

inside forward Bobby Cameron and 18 year old local boy John Hawksby replacing

Smith and Revie. The match was Hawksby's first and he marked it with the

opening goal, while McCole weighed in to produce a 2-0 scoreline. Hawksby

scored the first Leeds goal the following game, too, as Taylor kept faith

with a winning side. Grainger, Peyton and McCole were the other scorers

as Leeds drew 4-4 in the return against Bristol Rovers.

Yet another switch came in the next match, with Tommy Murray getting

his chance in place of Hawksby for a trip to Southampton. Leeds won 4-2

with goals from Grainger, Cameron, Francis and McCole, but the continual

changes made it impossible for the team to find any shape or rhythm. Taylor

seemed incapable of settling on his most effective line up, although injuries

and poor form left him few alternatives but to fiddle while Rome smouldered.

In an unwitting glimpse into the near future, Leeds swapped their standard

kit of blue shirts, white shorts and blue and gold socks for an all white

strip, trimmed with blue and gold, for the home game against Middlesbrough

on 17 September. The match finished in a spectacular 4-4 draw, but the

normal club colours were quickly restored.

That match somehow encapsulated the whole season for Taylor and his men.

The manager's continual chopping and changing brought no solutions, just

uncertainty and inconsistency. Sloppy defending had seen Leeds concede

92 goals in 1959-60. Relegation brought no respite and Second Division

forwards gorged themselves, with the three keepers that Taylor used, Ted

Burgin, and the youngsters Alan Humphreys and Terry Carling, picking the

ball out of their vulnerable net 83 times.

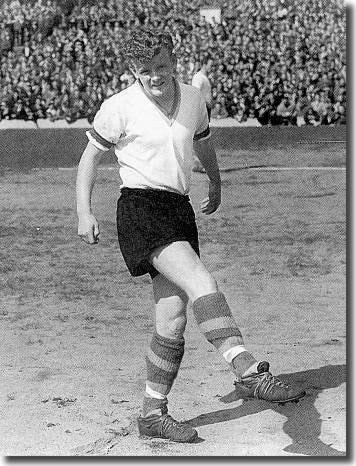

Bagchi and Rogerson: 'Among those stationed in front of the novice goalkeeper,

Freddie Goodwin, had joined Leeds to reignite a stalled career over the

Pennines at Manchester United. A former "Busby Babe", he had

shone intermittently at Old Trafford after graduating into the first team

in the aftermath of the Munich disaster but could never quite convince

Matt Busby that he had sufficient class to prosper at the highest level.

Originally a midfielder, he was converted to centre-half in the hope of

capitalising on his perceived versatility.

'Chronically one-paced and over-reliant on his brute strength, he nevertheless

had much to offer a struggling side. Good in the air and blessed with

natural authority … unfortunately, in contradiction to all his other admirable

leadership qualities, he lacked composure. His method was redolent of

the 'get some blood on your boots' approach loved by fans, but it failed

to mask his technical flaws.

'Managers love forceful characters and are willing to excuse many defects

if effort is always shown - but it can have its downsides. Goodwin managed

to persuade Taylor that Leeds should adopt a man-to-man marking system.

It enabled Goodwin to exploit his powerful tackling style, but other players

were run ragged tracking attackers all over the park. Charlton hated it

but reluctantly deferred to his senior colleague.'

back to top

In sharp contrast to the shaky rearguard, the United attack, spearheaded

by John McCole, did well. McCole carried on where he left off in the previous

season, scoring 20 goals in the League, following on from 22 the year

before. He also provided a good return in a new competition, the Football

League Cup, the brainchild of League secretary

Alan Hardaker. It was to be several years before the public embraced

the competition, but Leeds enjoyed some good performances in the trophy's

debut season.

Don Revie scored the club's first goal in the competition, hitting the

first in a 3-1 replay success at Blackpool, with McCole and Grainger finishing

the job. A 4-0 win at Chesterfield followed and United hit four again

in the next round, at Southampton, but still lost in one of the most remarkable

games in the club's history.

The Saints stormed into a 4-0 lead with Derek Reeves scoring all four

goals. Leeds showed uncharacteristic spirit by pulling level with goals

from Noel Peyton, McCole, Jack Charlton and a Bobby Cameron penalty. But

with  just

25 seconds remaining Reeves crowned a personal triumph by netting his

fifth in an amazing game which went on until 10.10pm because of two floodlight

failures, making it the longest-ever match in England.

just

25 seconds remaining Reeves crowned a personal triumph by netting his

fifth in an amazing game which went on until 10.10pm because of two floodlight

failures, making it the longest-ever match in England.

Both teams finished the match a man short. Southampton goalkeeper Ron

Reynolds had gone off while United full back Alf Jones, who had only recently

regained his first team place from Terry Caldwell, was withdrawn following

a knee injury.

Matters continued in a haphazard way all season, with Taylor's indecision

and a bad run of injuries prompting the use of 27 different players.

Concentration and professionalism were sadly lacking, with much of the

blame laid at the doors of the manager. Eric Smith was appalled by what

he found when he arrived from Celtic: 'The club was fifth rate and the

players were undisciplined. It wasn't their fault. Jack Taylor had let

the thing go. I thought beforehand I was coming to a top club. I found

out otherwise in the first three or four days. We would go on long training

runs and at the end, some players, quite senior players, would walk in

with ice lollies in their hands.'

The problem was not that Leeds were doing particularly badly. Indeed,

although they dipped at times into the very lowest reaches of the table,

they never looked in serious danger of a second successive relegation.

However, for a team which had been in the top flight so recently, they

contrived to look very mediocre indeed, against even the most limited

opposition. There was an air of despondency and resignation around Elland

Road, with team spirit virtually non existent and discipline in shreds.

Apathy set in amongst the fans, and gates dwindled significantly. Only

the presence of the bigger sides could generate any interest and the average

home gate was below 14,000, lower than it had been at any time since the

very first steps of Leeds United as a Second Division club in the 1920's.

Many matches saw less than 10,000 hardy souls braving the elements in

search of what little entertainment could be had at Elland Road.

In fact, the only party who seemed to give a damn were the shareholders,

dismayed at seeing the value of their 'investments' plummeting. An extraordinary

general meeting was forced in December 1960 amid demands for a vote of

confidence in the board. The arguments were long and passionate, but in

the end a declaration of support was carried by a poll of seven to one.

However, the unrest was acknowledged and changes were afoot. Harry Reynolds,

a board member since 1955, became increasingly dominant behind the scenes.

He eventually went on to succeed chairman Sam Bolton, who was becoming

weary at having to lead the club through such desperate times. Reynolds

was an eccentric self-made millionaire who continued to live in a two-up,

two-down terraced house despite having made a fortune as a steel stockholder

after starting out in life as a railway cleaner and fireman. He was born

in Holbeck, just a few minutes' distance from Elland Road, and was a lifelong

Leeds fan, nurturing a vision of the club as a leading power in the land.

The boardroom revolt coincided with a brief revival in the club's results

on the field and they went through December and January undefeated in the league, winning five of their eight games and climbing to ninth

in the table from a lowly fifteenth spot.

in the league, winning five of their eight games and climbing to ninth

in the table from a lowly fifteenth spot.

But, just as it seemed the team's fortunes were looking up, those of

Don Revie were in sharp decline.

His appearances all season had been sporadic as his form and confidence

suffered, and he chose to surrender the captaincy, arguing that the fates

did not smile on his leadership. Freddie Goodwin took on the responsibility

but enjoyed no better luck with either consistent team selections or results.

Revie played his final game of the season in a 3-0 win at home to Southampton

on January 14 as his thoughts turned to the future and a potential move

into management.

Revie kept his ambitions largely to himself, although Taylor relied on

his experience and capacity to evaluate a player. The manager one day

invited both Reynolds and Revie to travel with him to look at a player

in Bolton. On the trip, Reynolds spoke of his hopes for the club. His

views on the way forward coincided in many respects with Revie's ideas

about the game, and a bon of mutual respect was forged between them.

The prospect of Revie's departure was not a matter of great concern to

the club. At thirty-one the former England international was already past

his best when he joined from Sunderland in November 1958. Anxious to secure

a player-manager's job as his on-field career drew to a close, he had

applied for the job at Bournemouth in February 1961. Chester City and

Tranmere Rovers were interested in him and Adamanstown from Australia

held out the promise of a five year contract as player-coach.

back to top

However, events for Revie and Leeds United were soon to take a startling

turn.

The team's strong form around the turn of the year had proven to be a

mere flash in the pan and all the old failings came flooding back in February.

Four straight defeats and 13 goals conceded were enough - the new board

met behind closed doors to discuss the situation and Harry Reynolds pressed

for change. Jack Taylor had the final twelve months of his three year

contract still to run, and the miserly board were apprehensive about paying

out the £2,500 it would take to terminate his contract. Reynolds decided

to push the issue and met Taylor to tell him of the board's concern, hinting

that he would be pressing for the manager's dismissal.

Leeds managed to beat Norwich 1-0 at Elland Road on 11 March to end their

losing run, but Taylor had had enough and decided to call it a day, resigning

a couple of days later, despite his team being in a comfortable ninth

spot. There were no protests and the story merited few newspaper headlines.

Even the local paper, the Yorkshire Evening News, contained only

a fleeting report that club secretary Cyril Williamson would assume managerial

responsibilities pending the appointment of a successor. Sam Bolton admitted

to being more concerned with arrangements for that week's FA Cup semi-final

between Leicester City and Sheffield United, to be staged at Elland Road.

'We have not yet had time to consider an official appointment,' a stressed

Bolton said. 'We shall give the matter plenty of thought in the near future.'

However, Ronald Crowther, the editor of the paper and a long time supporter

of the club, played a part in resolving the issue. Crowther had already

written angrily in condemnation of the directors, 'It will not surprise

me if United carry on with a secretary-manager - Mr Williamson - at the

helm, with chief coach Syd Owen responsible to him for team affairs.'

Revealing the insecurity that would always haunt him, Don Revie asked

Crowther to draft his letter of application for the Bournemouth post.

Crowther instead pressed Revie to apply for the Leeds job.

It is the stuff of legend that Revie asked Reynolds for a reference.

The director wrote the letter, recommending Revie in glowing terms, but

paused as he did so and, considering his man's qualities, decided to rip

up the letter and exploit the potential himself. He managed to persuade

his fellow directors to give Revie the opportunity to begin his management

career in West Yorkshire, although when Leeds told Bournemouth that it

would cost them £6,000 to sign Revie, the South Coast club were given

considerable food for thought. The Times celebrated the historic

milestone with a terse and economic paragraph: 'D Revie, the Leeds United

inside-forward, was yesterday appointed team manager of the club in succession

to Mr J Taylor, who resigned on Monday. He has been given a three-year

contract. Revie will go on playing as long as he can.'

The beggars on the board could not afford to be choosers - two years

before, when they had appointed Taylor, even as a First Division club,

they had  struggled

to find a manager. As a side struggling in the depths of Division Two,

it would be doubly difficult to do so.

struggled

to find a manager. As a side struggling in the depths of Division Two,

it would be doubly difficult to do so.

Bagchi and Rogerson: 'In reality, therefore, the Leeds board had little

choice but to take the radical option and appoint Revie. Mired in the

lower half of the Second Division, they were palpably less marketable

to the ambitious or established manager than they had been two years previously.

After such a variety of managers and methods since the war, it was little

wonder that Eric Stanger in the Yorkshire Evening Post concluded:

"Nothing would benefit Leeds United more than a long stable period

of sound management. In fact, in their financial position, it is their

only hope for the future."

'Not only was Revie available, affordable and impressively full of ideas,

he was also, ideally, aware of the staff's shortcomings and the precariousness

of the club's standing at the bank. Crucially, he was far more likely

to accept the offer than any other candidate suited to the job.

'Three days after Crowther's erroneous prediction, the die was cast.

The thirty-three-year-old Revie was appointed on a three-year contract

- on terms markedly inferior to those that Taylor had enjoyed. His pay

was pegged at the £20 maximum, which had until recently been the maximum

wage. The Leeds Board were insistent that Revie should keep his 'playing'

contract for as long as possible. It was far cheaper that way. Desperate

to stay in football and singularly unsuited for the stock career route

of the ex-professional running a pub, Revie knew he had little option

but to agree. He never forgot their initial caution, hardly a brilliant

tactic to adopt with one so temperamentally vulnerable. In future, even

if their compromised position at the bank had given them little choice,

they would pay a heavy price for their attempt to screw him.'

A marriage made in heaven had an unpromising courtship.

Revie's first game involved a trip to struggling Portsmouth on 18 March.

The line-up in that first game read as follows: Alan Humphreys; Alf Jones,

John Kilford; Bobby Cameron, Freddie Goodwin, Peter McConnell; Gerry Francis,

Peter Fitzgerald, Jack Charlton, Biily Bremner, Colin Grainger.

Revie chose to spring a surprise by aping a decision of former Elland

Road boss Major Frank Buckley. Back

in the 1950s the Major had decided to experiment with centre half John

Charles in the forward line. Now Revie broke the news that his argumentative

centre half Jack Charlton would be asked to repeat the trick by wearing

the number nine shirt.

Charlton had often clashed with Revie since his arrival at Elland Road

in 1958 as a player, and the defender was apprehensive about the move:

'I tried my best, but the No 9 shirt didn't feel right to me. I didn't

know what to do, and nobody showed me. I remember Joe Shaw of Sheffield

United laughing at me, I was making such a mess of it. You are the wrong

way round up there. The ball comes to you when you have your back to the

goal and I prefer to be facing it.'

Despite all his reservations, Charlton somehow managed to get on the

scoresheet, hitting Leeds' goal in a disappointing 3-1 reverse. Revie

persevered with the experiment, only withdrawing Charlton when Goodwin

was unavailable. The manager also blooded a promising new talent on the

left wing.

back to top

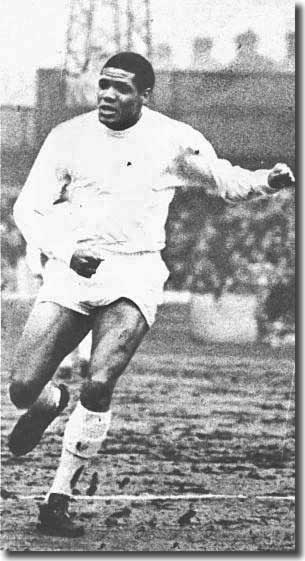

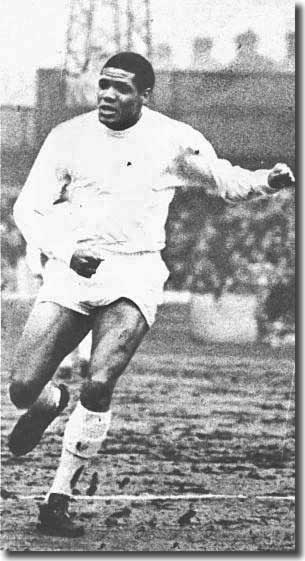

The twenty-year-old black South African Albert

Johanneson, later to be christened the Black Flash, arrived at the

club in April after Revie was tipped off to his talents by a school teacher.

No transfer fee was involved, just the cost of transport from Johannesburg,

and the young winger joined his countryman Gerry Francis at Elland Road.

It took only a couple of training sessions to convince Don Revie of the boy's

talents, and he was pitched into the first team. He was only a shadow

of the exciting talent he later became but did enough in a closing run

of five games to excite tremendous interest.

took only a couple of training sessions to convince Don Revie of the boy's

talents, and he was pitched into the first team. He was only a shadow

of the exciting talent he later became but did enough in a closing run

of five games to excite tremendous interest.

With Charlton managing a further four goals to add to the one he hit

at Portsmouth, Leeds squeezed enough points out of the final few games

to secure Leeds' Second Division status, even though the only win came

from an extraordinary 7-0 drubbing of already relegated Lincoln City.

Those two points were enough to end any lingering threat of relegation

with a couple of games remaining.

It had not been an auspicious start to a fledgling management career,

but Revie did well to get any return at all from an ailing and dispirited

squad. The Elland Road support were not impressed, however. The cynical

jeer of 'Here come the mugs' which drifted from the terraces was by no

means the harshest of the taunts the Leeds team suffered in this dreariest

of seasons - the final home match of the season against Scunthorpe United,

while not a major attraction could draw a crowd of just 6,975, the lowest

home attendance since 1934. There was much work to do if the hopes of

Revie and Harry Reynolds were to be realised, but at least the devastating

impact of two successive relegations had been avoided.

Other Football Highlights from 1960/61

- English football was only days away from its first national strike

when the Football League backed down in its long running dispute with

the PFA. The arguments over player's wages and the terms of their contracts

had dragged on for years. There was a maximum wage of £20 a week in

the season and £17 during the summer and players were not allowed to

move to a club of their choosing at the end of a contract. After five

hours of last ditch talks at the Ministry of Labour on January 18, the

League finally agreed to abandon the regulations

- The moment that the maximum wage was established Tommy Trinder, the

Fulham chairman, made Johnny Haynes the first £100 a week footballer

in England. That kept Haynes in England, but Italian clubs raided for

the best of British talent - Joe Baker moved from Hibs to Torino for

£73,000, Denis Law Manchester City to Turin £100,000, Jimmy Greaves

Chelsea to AC Milan £80,000 and Gerry Hitchens AC Milan to Inter Milan

£80,000

- England beat their bitterest rivals Scotland 9-3 on 15 April at Wembley,

with Jimmy Greaves scoring a hat trick and Bobby Smith and Johnny Haynes

both getting two

- Sir Stanley Rous was elected the president of FIFA. Denis Follows

replaced him as the secretary of the Football Association

- Everybody believed that the Double would never be achieved in modern

times, but Spurs and their cultured Irish captain Danny Blanchflower

did the impossible this year. Tottenham had a record breaking start,

winning their first 11 league matches and only dropped one point in

the first 16 games. They were so far ahead by Christmas that bookmakers

refused to take any more bets on them. They wrapped the title up on

17 April with three games still to go. Then they completed the job by

beating Leicester City 2-0 at Wembley to win the FA Cup

- Rangers reached the final of the inaugural European Cup Winners' Cup

before losing 4-1 on aggregate to Italy's Fiorentina. The Glasgow club

did manage to win the Scottish championship and the Scottish League

Cup, however

- Peterborough in their first season in the league raced through the

Fourth Division and were promoted as champions, scoring a record 134

goals. Terry Bly was their leading marksman with 52 goals, a post-war

record

- Real Madrid's perfect European Cup record was ended and Portugal's

Benfica beat Barcelona 3-2 in the final

Relegation

is never a pleasant experience for anybody, but Leeds United manager Jack

Taylor found it particularly hard in 1960

when, within a year of him taking over at Elland Road, the club lost their

First Division status. He felt let down by the players and decided that

drastic action was called for if the club were to recover their top flight

status quickly.

Relegation

is never a pleasant experience for anybody, but Leeds United manager Jack

Taylor found it particularly hard in 1960

when, within a year of him taking over at Elland Road, the club lost their

First Division status. He felt let down by the players and decided that

drastic action was called for if the club were to recover their top flight

status quickly. the

fundamentals of fitness in his wartime service with the Reconnaissance

Regiment in France after D-Day. He was temperamentally and professionally

qualified for the position of trainer. One of the first generation to

take the FA Coaching Certificate, he supplemented his tactical acumen

with exploratory studies in physiology and, more unusually, also dabbled

in the avant-garde sports sciences of kinesiology and biomechanics. He

had a stormy start with his new charges, who were contemptuous of his

dedication to their development, and had many a run-in with that self-styled

'one man awkward squad', Jack Charlton. Yet barely a year after joining

Leeds, he was summoned to Lancaster Gate and offered the prestigious job

of putting England squads through his revolutionary sequence of sadistic

drills, a position he was to occupy from 1966 right through to 1977.

the

fundamentals of fitness in his wartime service with the Reconnaissance

Regiment in France after D-Day. He was temperamentally and professionally

qualified for the position of trainer. One of the first generation to

take the FA Coaching Certificate, he supplemented his tactical acumen

with exploratory studies in physiology and, more unusually, also dabbled

in the avant-garde sports sciences of kinesiology and biomechanics. He

had a stormy start with his new charges, who were contemptuous of his

dedication to their development, and had many a run-in with that self-styled

'one man awkward squad', Jack Charlton. Yet barely a year after joining

Leeds, he was summoned to Lancaster Gate and offered the prestigious job

of putting England squads through his revolutionary sequence of sadistic

drills, a position he was to occupy from 1966 right through to 1977. Goodwin

remained in the centre of defence, with Bremner and Revie in tandem on

the right and big John McCole leading the line.

Goodwin

remained in the centre of defence, with Bremner and Revie in tandem on

the right and big John McCole leading the line. just

25 seconds remaining Reeves crowned a personal triumph by netting his

fifth in an amazing game which went on until 10.10pm because of two floodlight

failures, making it the longest-ever match in England.

just

25 seconds remaining Reeves crowned a personal triumph by netting his

fifth in an amazing game which went on until 10.10pm because of two floodlight

failures, making it the longest-ever match in England. in the league, winning five of their eight games and climbing to ninth

in the table from a lowly fifteenth spot.

in the league, winning five of their eight games and climbing to ninth

in the table from a lowly fifteenth spot. struggled

to find a manager. As a side struggling in the depths of Division Two,

it would be doubly difficult to do so.

struggled

to find a manager. As a side struggling in the depths of Division Two,

it would be doubly difficult to do so. took only a couple of training sessions to convince Don Revie of the boy's

talents, and he was pitched into the first team. He was only a shadow

of the exciting talent he later became but did enough in a closing run

of five games to excite tremendous interest.

took only a couple of training sessions to convince Don Revie of the boy's

talents, and he was pitched into the first team. He was only a shadow

of the exciting talent he later became but did enough in a closing run

of five games to excite tremendous interest.