|

|

|

Miscellaneous

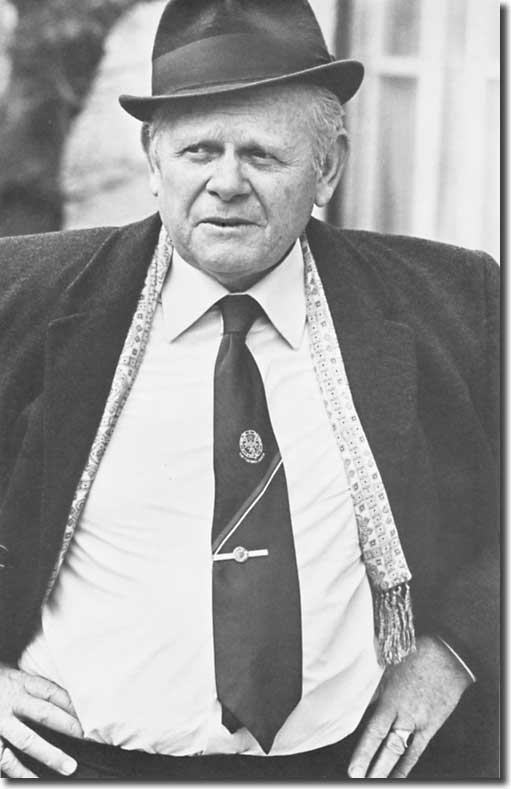

Alan

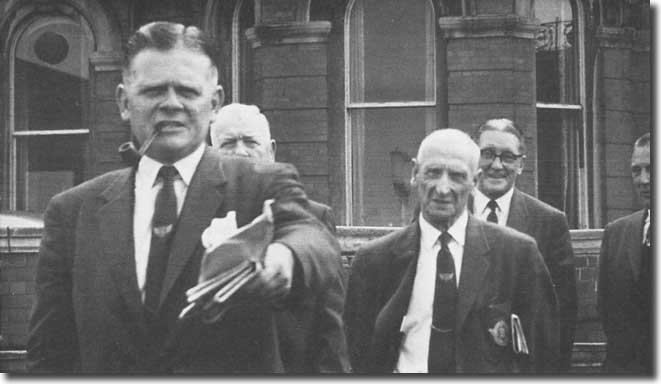

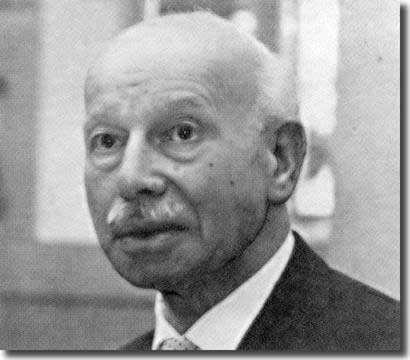

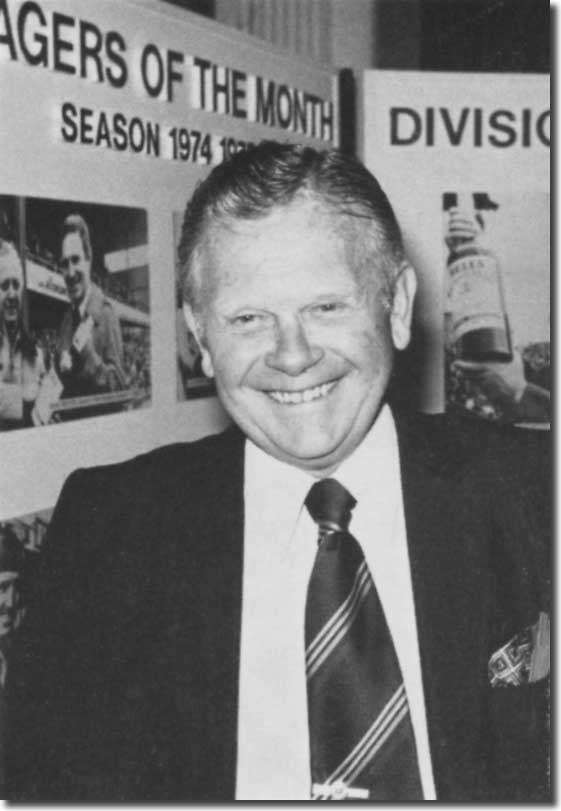

Hardaker - Revie's Nemesis

Generally considered an obstinate autocrat, Hardaker's public profile

was far higher than that of his predecessors. He was a key figure in the

game in the 1960s and 1970s, a champion for reform. Hardaker felt his prickly reputation was undeserved; in his autobiography,

Hardaker of the League, he confided: 'One of the few things I have

come to be certain about in football is the impossibility of attempting

to be a just and forward looking administrator as well as generally popular.

For every person who thinks a decision is right, there is another who

will condemn it as a sin against the game in general and himself in particular. 'I have been described, among other things, as "the League's most

celebrated enforcer", "the great dictator", "football's

Godfather", "a cross between Cagney and Caligula", "St

Alan of St Annes" and even, so help me, "Lytham's answer to

Idi Amin". The fact of the matter is that I have never been anything

more than a paid servant responsible at all times to the president and

members of the League Management Committee. 'My job has been to implement decisions and rules and to do everything

in my power to ensure that the League survives and prospers. It has never

been part of my brief to please people and, in any case, I believe it

is a mistake to tiptoe through life just to avoid treading on a few feet.' Many of Hardaker's insights and predictions have proven startlingly accurate;

it is clear he was something of a visionary. He would have despised the

financial obsessions of the modern day game, and undoubtedly he would

have vigorously opposed the establishment of the Premier League as being

against the best interests of the other 72 clubs. Hardaker's relationship with Don Revie was particularly testy: the United

manager had a reputation for being the consummate professional, willing

to do anything to further the interests of his club; Hardaker was notoriously

difficult, and reserved his greatest bile for someone he considered deceitful

and manipulative. Plus they were both Yorkshiremen! Hardaker: 'I think Don Revie comes nearest to having all the qualities

and faults of the modern manager. He is a contradiction in so many ways.

He is a great family man, an engaging personality, acutely aware of his

responsibilities 'As secretary of the Football League I often found Don Revie, as the

manager of Leeds United, to be a pain in the neck. I had a job to do,

he had one to do, and our duties and obligations as we saw them frequently

collided head on ... He only wanted his team to play when, in his own

mind, they were sure of winning ... Unless he could control everything,

he seemed to feel the dice were being deliberately loaded against Leeds.' Peter Lorimer spoke years later of their serial dispute: '[Revie] didn't

want to make friends ... One of the biggest things he did wrong for himself

as a manager was to become a great enemy of Hardaker, who made things

tremendously difficult for us. Alan Hardaker had a personal thing about

Don Revie, but Don was that kind of man. He could make enemies. He was

such a professional and if there was any rule he could use, and he was

entitled to use it, he would go for it.' In Don Revie: Portrait of a Footballing Enigma, Andrew Mourant

described events which were sadly typical of the difficult relationship. 'Revie had offended Hardaker ... by an oblique approach to the League

secretary's subordinates, with the aim of bringing forward by 24 hours

a League Cup-tie against Bristol City. It was the impropriety of Revie

seeking to involve his juniors that had made Hardaker especially indignant.

On another occasion, Hardaker gave Revie short shrift when the Leeds manager

asked for a postponement because three of his key players were badly injured.

Hardaker noted drily that not only did all three make sufficiently miraculous

recoveries to play, but one scored twice and another was, by general consent,

the man of the match.' In the closing weeks of the 1971/72 campaign, with United pursuing the

League and Cup Double, there was a more memorable spat, as recalled by

Rob Bagchi and Paul Rogerson in The Unforgiven: The Story of Don Revie's

Leeds United. 'With the FA Cup final looming, Leeds once again approached

… Hardaker to have the club's outstanding fixtures rescheduled. Once again

Revie was rebuffed, apparently because the move would have compromised

England's commitments in the European Nations Cup and Wolves' clash with

Spurs in the UEFA Cup. To Leeds' supporters it seemed as if the League's

principal remit was to stop the club winning trophies. 'Whatever Hardaker's merits, his personal enmity toward Revie ensured

that the club would receive no favours while he was in charge. His successor,

the lugubrious Graham Kelly, is frank about the two men's estrangement,

pointing out that 'Hardaker loathed Revie with a vengeance that can only

have been reserved for a fellow Yorkshireman who he felt had twisted his

way to the top."' There was little improvement when Revie was appointed England manager,

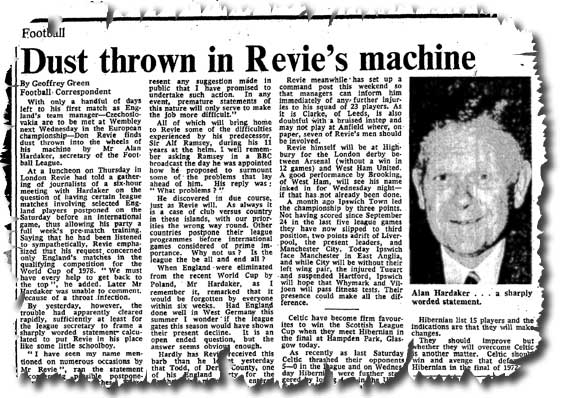

with Hardaker, one of the few who had misgivings, telling anyone at the

FA who would listen that they needed their heads examining. Hardaker had regular disagreements with Revie during his time at Lancaster

Gate. There was an acidic episode in November 1975 following a draw in

Lisbon which left England with only a thin chance of qualifying for the

European Championship quarter finals. Revie had pleaded for a suspension of weekend League matches before an

international and more time to prepare the team. Hardaker retorted, 'It

would not have made a scrap of difference ... I am a cynical man and it

sounded to me that we smacked of excuses before we even left for Portugal.

We must face up to the fact that we were not good enough. If we had the

same national pride as Wales [who had qualified] instead of playing for

all these big bonuses we might go somewhere. At the moment it is all money,

money, money.' Revie complained, 'Compared to other countries we have an amateurish

outlook but expect professional results at international level.' Hardaker snapped: 'It is Revie's approach to administration that is amateurish

... Revie wants it all his own way, just as he wanted his own way when

he was at Leeds.' Hardaker was disgusted but unsurprised when Revie took a job managing

the Hardaker: 'Soon after the end of [the 1969/70] season ... I went to Leeds

to speak at a businessmen's lunch... One chap ... asked me what I felt

like, being the cause of Leeds losing three trophies. I replied that ...

Leeds had managed to lose the three trophies all by themselves. My explanation

was met with a heavy, unforgiving silence. I think the attitude of Leeds

to it all can best be captured by a comment at the time, not from Don

Revie but from Jackie Charlton. He proclaimed, in an article, that Leeds

could have won all three trophies "if only everyone had co-operated

with us". 'I was called every name under the sun after [the 1971/72 season] ...

The fact of the matter is that it was Leeds United's own fault that they

did not go to Wembley as League champions. Earlier that season there had

been a period when floodlights were banned. The ban ended, with plenty

of advance warning, at midnight one Wednesday and Newcastle, aware of

growing fixture problems, generously agreed to bring forward their match

with Leeds to the following evening. Thursday night football is unusual,

I agree, but this particular game was scheduled to take place right at

the end of the season, when fixture congestion would be at its heaviest.

Newcastle genuinely wanted to help, and so I put their proposition to

Leeds. But Don Revie rejected the idea out of hand. Leeds, he said, never

played on Thursdays. 'Now, as it happened, Newcastle were going through a very bad spell when

they offered to play Leeds that Thursday night. They had been hard hit

by injuries and had lost their touch completely. I do not think there

is any doubt that Leeds would have beaten them; in fact, earlier in the

season, Leeds had scored five goals against Newcastle. The return game

at Newcastle was duly played a fortnight or so before the final, however,

and by this time there had been a change in Newcastle's fortunes. Their

injuries had cleared up, they were beginning to put their game together

and, sure enough, they beat Leeds with a single goal by Malcolm Macdonald. 'Revie was also a man with very definite ideas about referees. His most

definite ideas, oddly enough, seemed to be about those who were strongest

and tolerated least nonsense. Very often, Don would not speak to me personally

about this. I would get second and even third hand messages... One message

I got was from the assistant secretary at Leeds saying he had been instructed

by Mr Revie to speak to me because he had noticed that the referee for

their next match had been changed. Mr Revie, furthermore, did not like

the replacement and 'Don Revie's appointment as England team manager was a classic example

of poacher turning gamekeeper, and very quickly after his appointment

I discovered that Don now saw things in an entirely new light. In fact,

one of his first moves made me very angry indeed. 'The trouble followed a long talk we had in my office soon after his

appointment, a meeting which was also attended by Dick Wragg, chairman

of the senior international committee, and Ted Croker, the FA secretary.

It was a good, valuable meeting which I could not resist starting with

a promise. I promised Don the same co-operation that he had given Alf

Ramsey. There were smiles all round, with one smile perhaps a shade on

the frosty side. I then pointed out, quickly, that I would do everything

I could to help, and I meant exactly what I said. 'Don then raised the subject of postponing league matches involving England

players on the Saturdays before major competitive international games,

and I had to tell him immediately that "as things stood" this

was not possible. The reasons for my answer were various: the fixture

schedule was too tight for regular, large scale postponements, the League

had an obligation to keep faith with supporters who wanted to watch football

at least every other Saturday, and there was, too, a responsibility to

the pools. The clubs with England players, moreover, would be those most

likely to be involved in the final stages of the European competitions;

and Revie discovered for himself at Leeds the crippling effect of late

season congestion. I wonder how Don Revie of Leeds would have reacted

to the proposal by Don Revie of England. In any case, I was in no position

to promise, categorically, postponements before internationals. That was

the prerogative of the Management Committee and the clubs. 'I did, however, add one thing. "It is simply not on," I said,

"not at the moment anyway. There's a bit of time yet. You never know

what might happen in the future." My intention, in the spirit of

the meeting, was to avoid sounding obstructive. That was the last thing

I intended to be. I offered Don hope because an idea was forming in my

mind, but nothing I said could possibly have been construed as a promise. 'Don Revie's interpretation of it all was very different. Soon afterwards

he spoke at a sportswriters' lunch in London and inferred that I had promised

postponements before internationals. He said I had asked "for something

in exchange" and, while he did not want to say any more then, he

was confident there would be "full co-operation". He created

a strong impression that I had made him some definite promises, promises

I knew I had not made. 'The only action open to me was to issue a statement making it quite

clear that I had no authority to promise postponement of League matches,

and that I resented the suggestions made in public that I had promised

to undertake such action... I was not disputing the principle of postponing

matches 'The picture emerged, inevitably, of two men with pistols drawn but,

in fact, when Don Revie spoke to the sportswriters a date had already

been fixed for our next meeting. The purpose of that meeting, as I saw

it, was to come up with a solution which would satisfy both the League

clubs and the FA. 'I came up quickly with a plan which I thought would fit the bill ...

It was a very simple idea, really. It involved bringing matches forward

rather than postponing them. The mid week before a major international

would be left free of scheduled fixtures, which would enable Saturday

League matches involving international players to be brought forward a

few days. 'This, then, was the plan I had waiting for Don Revie when he came up

to Lytham for a second time ... There was some straight talking. "You

just can't run England like you ran Leeds," I told him. "At

Leeds the players were yours. Now you handle other clubs' players. Their

points of view have to be considered." I was not telling Don anything

new, of course. He realised the difference only too well.' .............................................................................................................................................................................................. Alan Hardaker was born in West Hull on 29 July, 1912. His father was

a Rugby League player with Hull and later a director of the club, and

his older brother also played for them, but Alan preferred football; as

an amateur centre-forward he scored a hundred goals in three seasons for

the Guildhall team, Municipal Sports. When he left school he went into

the family removals and haulage business. His father sacked him in 1929

for playing dominoes when he should have been working and he got a job

as an office junior in the Town Clerk's department. Hardaker played for Beverley White Star, champions of the East Riding

County League and Hull City's nursery side. He was given a chance with

the Tigers' reserves but Hardaker turned down an offer of The Hull City manager, Jack Hill, later told Hardaker that had he signed

he would have been sold to Bradford Park Avenue for £750. He went on to

play in the Yorkshire League for Bridlington Town and Yorkshire Amateurs

and came close to winning an amateur international cap, playing in two

trials, skippering the North in one of them. During World War II, Hardaker became a lieutenant-commander in the Royal

Navy and he captained the Navy's football team. When peace resumed, he

returned to Hull, but moved on to become Lord Mayor's secretary at Portsmouth

Council in August 1946. In 1951 Hardaker applied for an administrator's job at the Football League.

He was told by Portsmouth manager Bob Jackson that the League secretary,

Fred Howarth, was considering retirement from the post he had held since

1933, and the successful candidate would succeed him. Hardaker: 'Fred Howarth was approaching sixty-five at the time, and while

the Management Committee felt his retirement was imminent Fred himself

had no intention of releasing his hold on the job he had been doing for

more than twenty years. He did not want to retire and he certainly did

not want an assistant secretary on the staff waiting impatiently to step

into his shoes.' Out of 410 applicants, Hardaker was selected for a shortlist of six interviewees. Hardaker: 'The two-man committee consisted of Arthur Drewry, the League

President, and Joe Mears of Chelsea, and the first point Arthur Drewry

put to me was that they did not want anybody who knew anything about football.

They wanted an administrator. He then asked me if I regarded the job as

a stepping stone or whether I hoped to make it my career. I told them

I thought I was the man for the job, and that if they thought the same

I would be prepared to stay for ever. 'It was when we came to the question of salary that I made my one mistake.

I had been assured that Fred Howarth was going to retire in six months,

and so I told Drewry and Mears I was so confident I was the right man

for the job that I was prepared to back my judgement by coming to the

League for those six months at the same salary I had been getting at Portsmouth.

This was £760 a year and at the end of those six months my salary could

be reviewed. It was to prove a costly gesture. 'I met the full Management Committee shortly afterwards, they told me

the job was mine and my formal letter accepting the post was dated 1 May

1951. I accepted the job on the very clear understanding that my salary

was to be reviewed six months later and that when Fred Howarth retired

at about the same time I would become secretary of the Football League. 'Howarth had different ideas. He remained as secretary until 31 December

1956 ... But more than that: my salary was not reviewed after six months

and throughout those five years I received only the small annual increase,

around £50 a year, which went to every member of the staff. I was badly

let down by Arthur Drewry. 'It was made abundantly clear to me ... that I was not wanted. Fred Howarth

had nothing against me personally: he simply resented the idea of anyone

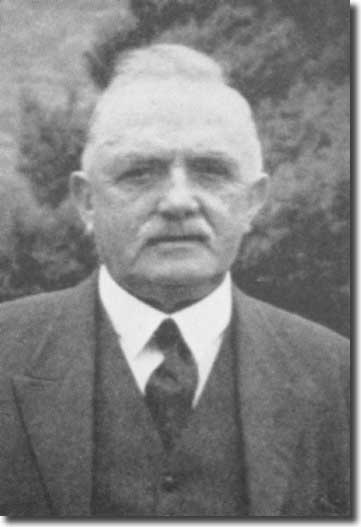

joining the League staff with the view, eventually, of replacing him. 'Fred Howarth was a small man of rigid habits and fixed principles ...

a man who was accustomed to having his own way in what was really a family

business. Tom Charnley, secretary from 1902 to 1933, was Fred Howarth's

father-in-law as well as his predecessor; Tom Charnley junior, was Fred

Howarth's right hand man until he resigned to go into business just before

I arrived; and Eric Howarth, Fred's nephew, was also on the staff. The

League, in other words, had been a family business for half a century

and I was the man who was threatening the line of succession. 'Nobody really had enough to do, but Fred Howarth loved it this way.

He was against change of any sort, particularly if it meant more work

for him or threatened the familiar, traditional flow of life at headquarters

... No proper records were kept: the filing system was a floor in the

attic. All relevant information appeared to be kept in the head of the

League secretary. This meant most inquiries, including those from the

Press, had to be referred to Fred Howarth. 'For two years I was given no work and no responsibility. It became clear

that retirement was the last thing in Fred Howarth's mind and when the

time came for my salary to be reviewed, as agreed, nothing was said ...

There were many moments when I felt like resigning. 'While my position was absurd, employed but not used, I did not waste

my time. I spent my days reading the minutes of the League right back

to 1888. I went through the lot of them, not once but many times. It was

a valuable exercise because 'I also decided, while going through the minutes, that if ever I did

become secretary I would be taking over a machine covered with rust and

cobwebs. The League was like a machine which had been lying in a corner

for nearly three quarters of a century and I knew that no matter how much

a machine like this was cleaned and oiled, and no matter how many parts

were replaced, it would never be a new machine. 'Eventually several members of the Management Committee put their foot

down. It was decided that I should attend all meetings. I could still

write shorthand and so, to keep my hand in, I took a full note of all

that was said. The next concession was a logical one: I was asked to draft

the minutes and I regarded this as a small but thoroughly worthwhile job

because I had long since come to the conclusion that League minutes in

the past had been written to hide rather than reveal. I was soon given

confirmation of this. 'I drafted my first minutes and took them in to Fred Howarth, He ran

his eye down them. "No, take that out," he said. "We can't

have that in - or that - or that." "But that's a resolution

passed by the committee," I protested. "Yes, yes, I know that,"

said Fred. "But it's ridiculous, of course, so let's forget about

it." This happened after almost every meeting. This was how the Football

League was run. If Fred Howarth did not like an idea it was never implemented

- or even recorded. There was no point in arguing. I often protested at

his censorship, but he would always say: "My boy, you'll find I'm

usually right." 'Change was inevitable, however, and my own star grew a little brighter

when my appointment as assistant secretary of the League was at last confirmed

at a meeting at Torquay on 5 July 1955. And it was just twelve months

later that the Management Committee decided to inform Fred Howarth that

he was ready for retirement. Arthur Oakley of Wolverhampton, who had become

President of the Football League when Arthur Drewry became Chairman of

the Football Association, was asked to tell Howarth during a representative

match at Molineux. 'The story was published next day - "League Secretary to Retire"

- and Fred Howarth almost exploded with rage. He denied it all over the

country, insisting, noisily, that he was not ready for retirement. It

was then discovered by the committee that Arthur Oakley had not told Fred

Howarth about the committee's decision. '"The Management Committee eventually decided this could not be allowed

to continue and it was agreed to tell him at the December meeting of 1956.

When the big moment came I was asked to withdraw from the room. "No,

no, Mr Hardaker," said Fred Howarth. "I'd like you to stay and

hear this." I thought it better to go, however, because I was embarrassed

myself and I did not want to embarrass him. 'I discovered afterwards that Howarth told the committee he had been

"most concerned" about the unfounded rumours of his retirement,

but that he had decided himself to retire on 31 December - not in 1956,

but in 1957! There was a long silence, and then Fred Howarth was told

that the committee wanted him to retire at the end of that very month,

the last day of 1956. I shall always remember his face when he came out

of that meeting. I felt very sorry for him. 'The committee then called me in and told me they felt it would be diplomatic

if they did not officially appoint me secretary until after Fred Howarth

had gone. Fred knew I was taking over, but never once, either by word

or gesture, did he acknowledge this. On New Year's Eve he came into my

room, put his keys on my desk and said: "You'd better look after

these until the Management 'My appointment as League secretary was confirmed at a meeting of the

Management Committee on 6 January 1957. The question of my salary was

raised. "Obviously you can't expect to start at the same salary as

Mr Howarth," I was told. "Well, it's hardly my fault that Mr

Howarth was underpaid all these years," I replied. "I won't

be starting for a penny less." I was in a mood to say anything, and

the outcome was that I started at £1400 a year when the figure the Management

Committee had in mind was £1100.' The League Management Committee granted the new man almost unlimited

powers and he quickly earned a reputation as a strident and confident

individual. He had already started exercising his power and earning a

reputation for the bloody mindedness for which he was always renowned,

as reported many years later by Brian Glanville in The Times: 'In his autobiography, Brian Mears, the former chairman of Chelsea, had

strange things to say about the club's failure to take part in the first

European Cup competition in 1955. "Chelsea could and should have

been the first English team to compete in the European Cup," he wrote.

"After we won the championship in 1955 the club was invited to play

in what is now the premier club competition. Sadly, the offer was refused

and another milestone was unattained. I am not sure why it was turned

down but the club probably just chickened out." 'It was Brian Mears' father Joe, the Chelsea chairman at the time, who

"chickened out" of the first European Cup, for reasons that

were plain enough. He was bullied into it, or out of it, by the notoriously

xenophobic Alan Hardaker, secretary of the Football League. '[Chelsea's] coronation as champions should have been perfectly timed

for them to take part in the newly-created European Cup, but the Football

League promptly 'advised' Chelsea not to participate. For the Football

League read Hardaker, secretary and unbending autocrat, who once told

me that he didn't like dealing with football in Europe: "Too many

w**s and d****s". His attitude was supremely negative and self aggrandising,

probably influenced by the fear that his own competition would be overshadowed

by the new one. 'A year later, Manchester United, and Matt Busby, their far seeing manager,

were made of much sterner stuff than Chelsea. As new champions, United

were determined to enter the European Cup and defied the Football League's

and Hardaker's attempt to ban them from doing so ... But Hardaker would

have his petty revenge. It was, as we know all too well, after a European

Cup match in Belgrade in February 1958 that the horrifying air crash at

Munich airport all but destroyed United's dazzling team and almost cost

the life of Busby. Jimmy Murphy, the assistant manager, patched up the

side so resourcefully that they managed to reach the semi finals of the

European Cup. 'In the close season, UEFA, in a generous gesture, invited United to

compete in the next European Cup as a mark of sympathy and support. Hardaker

and the Football League immediately objected, on the negligible grounds

that UEFA's own statutes permitted only national league champions and,

if not champions, the holder of the trophy, to participate. 'United appealed to the FA, who upheld their case, but the vengeful Hardaker

was not to be beaten. He now insisted the case went to an appeals body

made up jointly by representatives of the FA and the Football League.

There was no obvious precedent for such a strategy, but Hardaker got his

way. The joint commission was convened, it ruled by a majority against

Manchester United and Hardaker had won what would surely prove a pyrrhic

victory for xenophobia and his insular Football League.' Hardaker recalled matters very differently, laying the blame for the

decision squarely at the feet of Howarth and the Management Committee:

'The Football League Management Committee decided [the European Cup] was

something of a joke 'The League Management Committee made their first major decision on European

football at a meeting at the Great Western Hotel in Paddington on 5 July

1955. Arthur Drewry was in the chair and I was there as assistant secretary,

mouth shut, feet on the ground, just listening and learning. The private

minutes tell the story very briefly: "The League Secretary, Mr Fred

Howarth, reported that Chelsea FC had informed him that they had accepted

an invitation to participate in the competition between clubs from European

countries, and asked for the approval of the Management Committee. Although

of the opinion that they could not withhold permission, the Management

Committee instructed the secretary to ask Chelsea FC to give the matter

further consideration because they thought that their playing in such

a competition would not be in the best interests of the League." 'The Management Committee did not therefore, in so many words, forbid

Chelsea to take part, for the very good reason that they did not have

the power, but the meeting was unanimous that Chelsea should be requested

to stand down. 'I could at least understand the reason for the committee's attitude.

Chelsea had left their request very late and, as always, the committee

had to remember their collective responsibility to all clubs. The schedule

of the Football League was the tightest in Europe, and lack of time and

room to manoeuvre meant any new commitments had to be considered very

carefully indeed. 'What I could not understand was the lack of vision then shown by the

committee. They reached their decision about Chelsea in just a quarter

of an hour, which was fair enough considering everybody was in agreement,

but what astonished me was that the meeting then moved on to the next

item on the agenda. The subject of Europe had been dealt with to their

satisfaction in less time than it takes to smoke a small cigar. 'They did not for a moment wonder about the possibilities of European

football. No one said: "Right! Now let's look at the potential."

No one asked if the idea was good, or whether the organisation was right,

or what the benefits and disadvantages were likely to be. There was not

a glimmer of curiosity. The decision was taken and the subject forgotten. 'I still find it amazing that a subject as hugely significant as this

... could be treated in such a cavalier fashion. There was not so much

as a word or syllable uttered in doubt or question. The subject had been

talked about before the meeting, of course, and I knew pretty well what

the trouble was. The Management Committee were scared of the whole idea.

They saw it as a long term threat to their own competition ... They felt

they might be agreeing to something over which they had no control. 'This glorious piece of insularity was one of the Management Committee's

biggest mistakes, but having made it and moved on, they then managed yet

'Twelve months later Manchester United were the champions and their way

around the problem of getting League permission was altogether a more

subtle exercise. United simply informed the League that they had been

invited to compete in the European Cup through the offices of the Football

Association and that they had 'accepted in good faith'. Things had been

kept extremely quiet and I doubt if this would have been possible without

the personal friendship, in the background, of United's chairman Harold

Hardman and Fred Howarth. 'The Management Committee were no better prepared for United's request

than they had been for Chelsea's twelve months before. They had given

no further thought at all to the subject ... and they were again bowled

over by surprise. The committee's first reaction was to decide to ask

United to withdraw 'because of the possible effect on League attendances'

whatever that meant. 'United, however, did not bend their knee as readily as Chelsea. They

repeated that they had been invited by the Football Association. They

again added that they had 'accepted in good faith', an argument which

was aimed at the gentlemen on the committee - and most of them were gentlemen.

United followed this up quickly by disclosing that all arrangements for

their home and away ties with their first opponents, Anderlecht, had already

been made. Dates had been fixed, tickets printed, accommodation and travelling

arrangements organised. 'United's manoeuvre struck some of the Management Committee as sharp

practice, but it was their own fault... All United had done was outflank

them. The Management Committee minutes of 9 September 1956 duly recorded

that because "the club had entered the competition in good faith

at the invitation of the Football Association and because all the arrangements

for both the home and away games versus Anderlecht FC have been completed

... we accept that, at this stage, Manchester United could not cancel

their arrangements." 'It can now be argued, I suppose, that United did English football a

favour by forcing the Management Committee's hand. I think the committee

deserved their defeat, their lack of Hardaker supervised the move of the League's headquarters in 1959 from

Starkie Street, a converted town house in Preston, to the former Sandown

Hotel in Clifton Drive South, Lytham St Annes, following a request from

incoming President Joe Richards. It was bought for £11,000 and a six-month

renovation was carried out at a total cost of £40,000. Hardaker oversaw a number of innovations, such as capitalising on the

introduction of the Copyright Act in 1956 to charge for the use of fixture

lists, meaning that all Pools companies would have to pay for the privilege

of printing fixtures in their coupons. He oversaw a victorious test case

in 1959 against Littlewoods Pools to seal the deal. He was also integrally involved in a heated dispute relating to players'

contracts. In 1959, any player declining the offer of a new contract for whatever

reason was in a uniquely weak position. The club simply retained his registration

and were no longer obliged to pay him. They could sell him to whoever

they chose, but if the player refused to go he would again not be paid.

The argument in favour of both systems was that they prevented the wealthiest

clubs from acquiring all the best players and kept pay under control. The PFA, under their new chairman, Jimmy Hill, decided to challenge this

state of affairs. Hardaker said of the battle, 'Nothing in my time as secretary of the

Football League has been of greater significance to the professional game

... It was a bloodless revolution but it left football with bruises and

scars that are still painful and did much to reduce the game to its present

chronic state of financial ill health. It was a long and bitter fight,

full of heroes and villains, but I think posterity may have difficulty

in deciding exactly in which role to cast many of its principal figures.

Too many people Hardaker always accepted that players should be paid more and recognised

that the status quo could not be sustained. He tried to broker a compromise,

saying later, 'It could so easily have been different and certainly would

be if I had been the dictator so many people supposed me to be. I would

have retained a maximum wage - a good, healthy one related to the cost

of living and possibly graded through the divisions - but thrown it open

to the clubs to offer whatever incentives and bonuses they wanted ...

The clubs would have been able to keep a tighter rein on things when times

were hard both on and off the field. 'I put this plan to the Management Committee before the first serious

shots were fired. The standing rules would have required very little alteration

and I still believe this is a scheme the players would have accepted.

Unfortunately, I had not been secretary long enough at the time to have

any real influence and I was shouted down. 'There was too much suspicion on either side of the table and progress

was often of the 'one step forward, two steps backward' variety. The PFA

were convinced they had the Almighty on their side. I remember Joe Richards

saying at one meeting: "For the good of the game I suggest ..."

Jimmy Hill cut across him: "We're not interested in the good of the

game. We're only here to talk about our members." 'Cliff Lloyd and I did our best to find a key to it all and there was

even a point when we felt we might have succeeded... The plan, briefly,

was for a maximum wage of £30 a week for the next two years, no length

to contracts, which could be freely negotiated, retention on full wage

and the setting up of a joint negotiating committee. I took the plan back

to a meeting of clubs but, as usual, found the door to compromise already

shut and barred. 'The PFA 'The ultimate weapon of a union then as now is a strike, of course, and

the PFA used this threat as their final push. Their strike notice was

circulated a week before Christmas 1960 and was due to expire a month

later. I think the clubs should immediately have said to the players:

"Go on, then, strike." They should have been strong and put

their foot down. 'A big group of players made it clear that while they would go along

with the majority the last thing they wanted was a strike, and even many

of those who voted in favour might have discovered that when it came to

the point their resolution was not as strong as they thought. Even if

there had been a strike, however, it could have been a very good thing

... The two sides would have been forced to get together again and to

consider the whole argument from a wider and less selfish point of view.

The strike might have lasted a fortnight, but sooner rather than later

football would have been the real winner. 'The clubs, alas, showed no collective strength. Some were frightened

by the threat, and hoped that if they closed their eyes the problem would

simply go away, others were convinced in their own minds that the PFA

was bluffing, and there were those who stuck to their feudal belief that

the players should get absolutely nothing. It was in the middle of this

period of duress and muddled thinking, early in 1961, that the historic

decision to remove the maximum wage was taken. 'There was nothing remarkable about the way it happened. The clubs first

suggested that before the lid was removed there should be a maximum of

£30 a week for two years, which would have allowed the clubs to prepare

themselves gently for the demands to come. But the PFA held their ground

and so, finally and painfully, the point was conceded. There would be

no maximum wage from the start of the following season. 'A day or so later Fulham announced that they intended paying Johnny

Haynes £100 a week, an enormous wage in those days, and suddenly the floodgates

were open. 'To be fair, I do not think Fulham had much alternative. They had been

saying for a long time that Haynes, their star of stars, was worth £100

a week; but they had always been able to add that, unfortunately, they

were prevented from giving him this by League regulations. Now that bar

had gone and they had to pay up. 'At the same time as the clubs announced that they were prepared to remove

the maximum 'There had never been any doubt in my mind that the moment one player

stepped forward to challenge the legality of the old retain-and-transfer

system its days were numbered. That player proved to be George Eastham...

He decided he wanted to leave his club, Newcastle, and when they refused

to let him go he took a job outside the game in the South for five months

and began the long procedure of challenging the club's right to hold him

against his will. 'The Management Committee advised Newcastle to let Eastham go long before

the affair came to a head. Wilf Taylor, a member of the committee and

also a Newcastle director, was the go between and he made it clear many

times that if Eastham was not given his transfer the consequences could

be serious. 'You cannot win,' Wilf told his fellow Newcastle directors. "Eastham appealed to the Management Committee but Newcastle were sticking

to the regulations as they existed and therefore very little could be

done. The committee had to rule that it was 'purely a matter for club

and player'. Things were resolved in the end, of course, and in November

1960 Eastham moved to Arsenal; but by then he had also turned to the Law

and the days of the old retention system were numbered. 'The Law never hurries, however, and it was not until nearly three years

later, in June 1963, that the match between Eastham and Newcastle took

place in the High Court with Mr Justice Wilberforce as referee. 'I did not think Newcastle and the League had much of a chance and this

was soon confirmed when Mr Justice Wilberforce, who was at all times precise

and well ordered, began his judgement. The key to it all was his opinion

that the "rules of the FA and the regulations of the League relating

to the retention and transfer of players of professional football, including

the plaintiff, are not binding upon the plaintiff and are an unreasonable

restraint of trade."' In August 1965 Hardaker's canny intervention resolved a dispute between

the FA and the League clubs. The FA insisted that clubs signed declarations

that they had not made any illegal payments to amateur players. Hardaker: 'Club chairmen were being asked to guarantee that no illegal

payments were being made by any employee of their clubs. They were being

asked to carry the buck. It was an intolerable demand, an open invitation

to chairmen to get themselves into trouble about something over which

they felt they had no control.' He advised clubs to resign from the FA in protest, saying, 'You would

not be allowed It was decided that the FA could only be made to see reason by a show

of strength. Hardaker sent a letter to the clubs asking them each to submit

their resignation from the FA. Some did not get around to sending letters

but most did. Some straight talking took place and the FA duly announced

that the statutory declaration was intended primarily for amateur clubs,

ending the dispute at a stroke. Hardaker reigned at the League at a time when there were regular clashes

with the FA and he did everything he could to lessen their power over

the League, jealously guarding its autonomy. The disputes were wide ranging

and bitter and, ultimately, the biggest disagreement concerned finance. In March 1972, problems between the two reached new heights, and Hardaker

called a special meeting of club chairmen to discuss the problem. A dispute had been simmering for months as the League negotiated for

more control over its affairs, and was brought to a head over the fees

negotiated with the TV authorities for the live screening of the England-West

Germany European Championship clash at Wembley. A Joint FA and League Television Committee had been established for the

negotiation of fees for live television transmission of games. The Committee

agreed that Hardaker would take the lead as he was 'the most experienced

negotiator in all such matters'. However, without notice, FA members ordered

Hardaker not to speak and FA chairman Dr Andrew Stephen [assumed the lead

role]. This act of 'initiative' was symptomatic of the FA's arrogant attitude

towards what they considered a junior body. The event was a turning point for relations between the two bodies, with

some fears that the Football League would seek to break away from the

FA. Hardaker said at the time: 'Regretfully this means a state of open war

between the FA and the League, and it will be construed that the FA chairman

and vice chairman fired the first shots. It was certainly not the wish

of the League Management Committee. It appears to be a deliberate attempt

to start a war, and can only do tremendous damage to the game. The League

Management Committee have been bending over backwards to prevent a major

split, but now I have been instructed by the Management Committee to call,

as quickly as possible, a special meeting of the club chairmen. This will

be to discuss all facets of consultations with the FA on all matters.' In later years, he recollected, 'If we had not fallen out over this particular

issue, it would have been another. I was not even saying anything new,

when I announced a state of war, because the League and the FA have been

laying about each other for the best part of a century. It is a cold war,

of course. No triggers are squeezed, no blood is ever drawn, but it is

a war which has been spitting away ever since the Football Association's

muddled attitude to professionalism back in the 1880s led to the birth

of the Football League. 'The issue was the size of the fee to be asked for televising England's

European championship quarter final with West Germany at Wembley, a decision

which should properly have been made by the FA and League Joint TV Committee.

The fee most of the committee approved was £100,000, which meant that

after negotiation we would probably have got £80,000, but Andrew Stephen

and Harold Thompson, as chairman and vice chairman of the FA, took it

on themselves to accept £60,000. They claimed, in a statement, that they

had been "motivated by the desire to ensure that the enormous public

interest in the match should be satisfied". It was a decision they

took by themselves, contrary to the decision of the Joint TV Committee.

Denis Follows, the FA secretary, was sick at the time, and the Management

Committee had only agreed to go ahead on the clear understanding that

I should negotiate the fee in the temporary absence of Denis. 'Feeling between the two bodies burst into flame and at a special meeting

of League clubs all manner of sanctions One of Hardaker's major preoccupations was the desperate need to reform

the Football League structure. There were few who disputed the need to

change: attendances had been falling steadily since the heights reached

after World War II. Attendances in 1946/47 totalled 35.6m, and they continued

to grow, reaching a peak of 41.3m in 1948/49. By 1977, the total had fallen

to 27m. In 1963, Hardaker brought forward the so called 'Pattern of Football'.

It would have revolutionised the structure of the League, increasing membership

from 92 clubs to 100 and increasing the number of divisions from four

to five, with four up and four down promotion and relegation. He also

suggested the introduction of a new midweek cup competition to replace

the revenue lost by playing fewer League games. Hardaker: 'There was, at that time, no doubt in the minds of the League

Management Committee that the competition needed drastic surgery... The

Management Committee properly saw themselves as the game's trustees, and

the 'Pattern of Football' was their solution. It was their attempt to

strengthen and stabilise the oldest League in the world for generations

to come. They were concerned with the game not only in 1963 but in 1973

and 1983. 'The Management Committee then properly discussed it at great length,

and they were unanimous on all points except one. That was their big mistake.

I believe the omission of one paragraph was the reason the plan was eventually

thrown out. That paragraph was the final one in the plan I submitted.

What it said was this: "The Management Committee have given careful

consideration to all the views expressed by the Clubs and if the recommendations

are not acceptable to the required majority then the Committee can offer

nothing further which would be an improvement on the present arrangements.

They are also of the opinion that all the suggestions are interdependent

and would have no beneficial effect if they were not adopted as a complete

pattern." 'The Management Committee insisted on the deletion of this paragraph.

It was a major tactical error. The paragraph would have made it abundantly

clear that this was their last word on reorganisation. The plan itself

emphasised the seriousness of football's problems and its final few thoughts

would have forced the clubs to think very carefully indeed before rejecting

it. Its message could not be mistaken. It might even have swayed those

clubs who take natural delight in blocking progress. 'The Pattern was then put to League club chairmen at a meeting at St

Annes on 25 March 1963. It lasted two and a half hours and I thought it

was a very, very good meeting. Everyone who had anything to say was allowed

to say it and, while there was criticism of the plan, as a whole and in

part, nobody ridiculed it. 'We voted on the Pattern. Twenty-nine of the forty-nine votes were in

favour of changing the League to five divisions, each of twenty clubs,

and twenty-eight votes were cast for four up and four down promotion and

relegation. I knew the plan would need a three quarters majority - thirty-seven

votes - at the annual meeting, but I felt the way things went at the chairmen's

meeting was enormously encouraging. We had the nucleus of success. Only

nine clubs needed to be persuaded and the reshaping of the League would

be under way. 'All that was needed was a catalyst, an agent to spark off a reaction

- a new line of thought, an indication of united enthusiasm, some clear

speaking, anything that might have gingered these clubs into second thoughts.

That lead ought to have come from the Management Committee, of course.

They gave the Pattern their blessing, but they did not follow it up with

some determined selling. This was why the Pattern was rejected at the

annual meeting at the Cafe Royal the following June. The plan received

twenty-nine votes - eight short of the required three quarters majority

- because, quite simply, all the clubs stuck to their first opinion. They

had been given no reason or encouragement to change it. 'The debate on the Pattern was therefore pointless. It had as much spontaneity

as a familiar play. We listened to the same words and heard the same voices.

Those who were previously against the Pattern were still against it. Those

in favour had always been in favour. And, at the end of it all, surprise,

surprise, the Pattern was still eight votes short of getting its chance

to revitalise English League football.' The League framework was not changed, but the Football League Cup was

born; without the other changes, this only worsened fixture congestion.

The new competition was not a great success until its final was switched

to Wembley in 1967 with a place in Europe awaiting the winners. In December 1972, Hardaker pushed the reform agenda again with a document

entitled New Look for Football. Club chairmen were called to meetings

in London the following month to consider some far reaching proposals. Hardaker: 'It stressed the fact that gates were falling, offered eight

major points for discussion and invited comment. These points included:

five - or even, if they preferred, four - divisions of twenty clubs each;

the length of the season; promotion and relegation ... television; and

several ways of making the League more interesting, e.g. counting goal

difference instead of goal average, points for goals, and changing the

offside law. 'There was more talk, more heated disagreement, but this time one proposal,

or at least a variation of a proposal, did become a rule. Four up and

four down was proposed by Derby County at the annual meeting in June 1973,

but the Management Committee, by way of compromise, also proposed three

up and three down. Their feeling was that if the clubs rejected fours,

they might accept the lesser proposition; and, faced with a choice, that

is exactly what the clubs did. I think the committee were wrong. If they

had gone wholeheartedly for four up and four down (with no hint of compromise),

I think it would have gone through. But, once again, the Management Committee

wanted to 'Inevitably, there was soon criticism of three up and three down. It

was pointed out that the change simply meant more clubs were worried about

relegation, and that this, in turn, meant a loss of adventure and an increase

in fear and tension. Survival, it was argued, had become more important

than ambition. It is a point, but there is another side to the argument.

Three up and three down has injected new interest into games that would

otherwise mean nothing in the closing stages of the season; and so while

there may be more fear at the bottom, there is certainly less complacency

in the middle. And most spectators may feel that fear is the lesser of

the two evils. 'Football is now paying for the mistakes it made years ago. One of the

high hurdles has been the three quarters majority rule. Democracy works

slowly and carefully, and this can be good; but it sometimes holds things

up which need doing urgently. The main trouble, however, has been that

too many clubs never think about tomorrow. 'I still think something is going to have to be done even if it is later

rather than sooner. The game's problems will otherwise become completely

unsolvable. My fear is that nothing will be done until people themselves

change. If that is so, we must not hope for too much.' In June 1971, Hardaker was awarded an OBE in recognition of his services

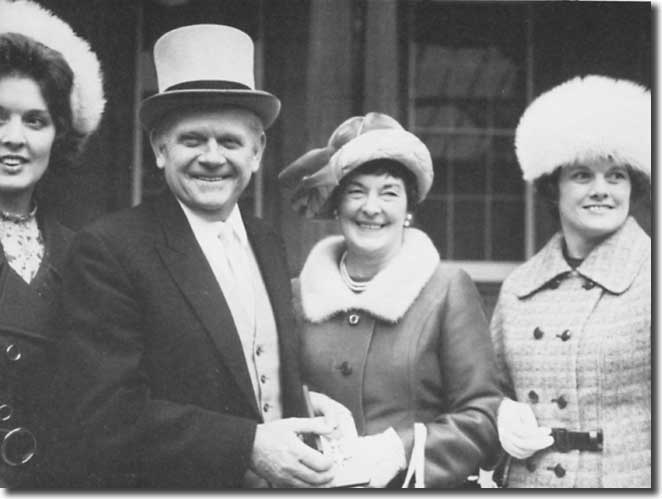

to the League. In 1979 he formally retired as secretary and was made Director

General of the Football League, with the brief of working on special projects,

one of which was a blueprint for football in the 1980s. He continued to be very active and remained so until his death from a

heart attack on 4 March 1980. He left a widow and four married daughters

and an estate valued at £58,838. Leeds

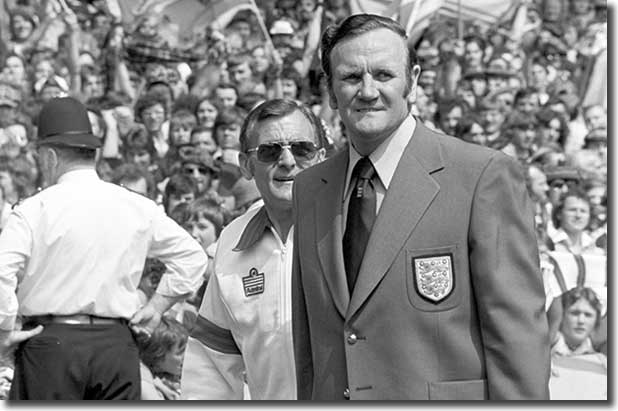

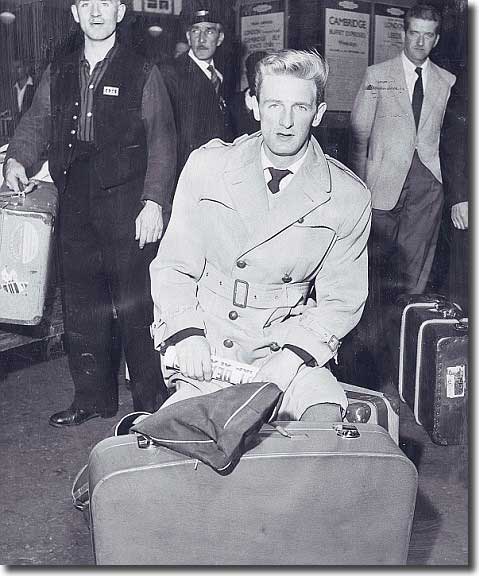

United manager Don Revie made a number of enemies during his career in

football, but there were few in whom he inspired greater irritation than

Alan Hardaker, the irascible Yorkshireman who served as secretary of the

Football League from 1957 to 1977.

Leeds

United manager Don Revie made a number of enemies during his career in

football, but there were few in whom he inspired greater irritation than

Alan Hardaker, the irascible Yorkshireman who served as secretary of the

Football League from 1957 to 1977. and

enormously hardworking. But I also know him, in a football sense, to be

totally ruthless, selfish, devious and prepared to cut corners to get

his own way, It is the rare combination of all these qualities which has

made him one of the game's outstanding managers.

and

enormously hardworking. But I also know him, in a football sense, to be

totally ruthless, selfish, devious and prepared to cut corners to get

his own way, It is the rare combination of all these qualities which has

made him one of the game's outstanding managers. Saudi Arabian national side: 'I can only hope he can quickly learn to

call out bingo numbers in Arabic.'

Saudi Arabian national side: 'I can only hope he can quickly learn to

call out bingo numbers in Arabic.' "he wondered if some arrangements could be made for a change."

I replied, not for the first or last time, that in no circumstances were

clubs allowed to pick their own referees.

"he wondered if some arrangements could be made for a change."

I replied, not for the first or last time, that in no circumstances were

clubs allowed to pick their own referees. before

internationals. I was simply objecting to Don Revie talking out of turn

and putting the League and myself in an impossible situation. Don knew

exactly what he was doing.

before

internationals. I was simply objecting to Don Revie talking out of turn

and putting the League and myself in an impossible situation. Don knew

exactly what he was doing. professional

terms in 1936, as he had progressed to the position of Lord Mayor's secretary.

He was the youngest holder of such a post in the country.

professional

terms in 1936, as he had progressed to the position of Lord Mayor's secretary.

He was the youngest holder of such a post in the country. it gave me background. It was a short cut to experience in a field about

which I knew very little.

it gave me background. It was a short cut to experience in a field about

which I knew very little. Committee

decide who my successor is going to be. I'm going home." That was

how Fred Howarth's twenty-three years as League secretary ended.

Committee

decide who my successor is going to be. I'm going home." That was

how Fred Howarth's twenty-three years as League secretary ended. and,

at best, a nine days' wonder. It took them just fifteen minutes to decide

that they did not want Chelsea ... to take part in the first European

Cup.

and,

at best, a nine days' wonder. It took them just fifteen minutes to decide

that they did not want Chelsea ... to take part in the first European

Cup. another.

They forgot all about the subject.

another.

They forgot all about the subject. foresight brought it upon them.'

foresight brought it upon them.' fought from deeply entrenched positions. Minds were closed and there was

no place for compromise ... There was blindness in both corners and football

is still counting the cost.'

fought from deeply entrenched positions. Minds were closed and there was

no place for compromise ... There was blindness in both corners and football

is still counting the cost.' slowly

advanced, the clubs slowly retreated, and in the middle, its teeth drawn,

was the Management Committee. Its members had been elected by the clubs

to do a job of work but were then prevented by those same clubs from doing

it.

slowly

advanced, the clubs slowly retreated, and in the middle, its teeth drawn,

was the Management Committee. Its members had been elected by the clubs

to do a job of work but were then prevented by those same clubs from doing

it. wage they also insisted that the retain-and-transfer system would have

to stand as "an integral part of the League's organisation".

Joe Richards told the players bluntly: "This is the final word of

the clubs." The players were not impressed and the strike notice

stood.

wage they also insisted that the retain-and-transfer system would have

to stand as "an integral part of the League's organisation".

Joe Richards told the players bluntly: "This is the final word of

the clubs." The players were not impressed and the strike notice

stood. to

take part in the FA Cup, you would not get any FA Cup final tickets, and

you would not receive any FA minutes. But that's about all.' Even if clubs

resigned from the FA, they would still be affiliated to their County Football

Associations and this would be their licence to continue playing football

in England.

to

take part in the FA Cup, you would not get any FA Cup final tickets, and

you would not receive any FA minutes. But that's about all.' Even if clubs

resigned from the FA, they would still be affiliated to their County Football

Associations and this would be their licence to continue playing football

in England. were

discussed, including, the most extreme, a boycott of the FA Cup. There

was another suggestion that the FA should pay for the privilege of having

League clubs in its knock out competition. A figure of £100,000 was mentioned.

The issue became so emotional that when we held another meeting it was

described in the papers as a 'war cabinet'. Fortunately, even though war

had been formally declared, no bullets were fired.'

were

discussed, including, the most extreme, a boycott of the FA Cup. There

was another suggestion that the FA should pay for the privilege of having

League clubs in its knock out competition. A figure of £100,000 was mentioned.

The issue became so emotional that when we held another meeting it was

described in the papers as a 'war cabinet'. Fortunately, even though war

had been formally declared, no bullets were fired.' be sure they were on a winner. It proved that compromise is by no means

always a sign of strength.

be sure they were on a winner. It proved that compromise is by no means

always a sign of strength.