Part 2 Home grown hero - Part

3 From Sweden to Liverpool - Part 4 Back from

the dead - Part 5 End of the line

Part 2 Home grown hero - Part

3 From Sweden to Liverpool - Part 4 Back from

the dead - Part 5 End of the line

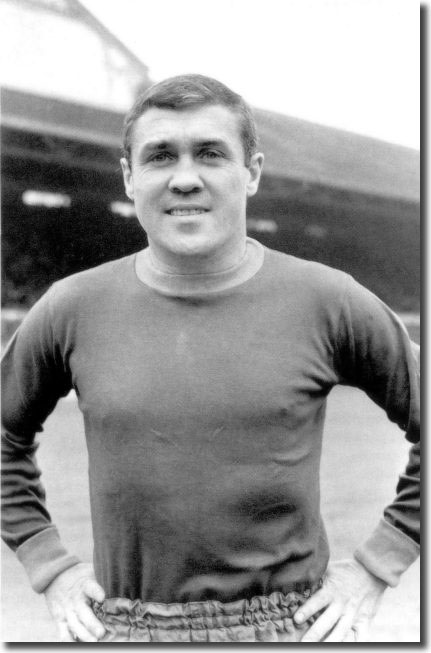

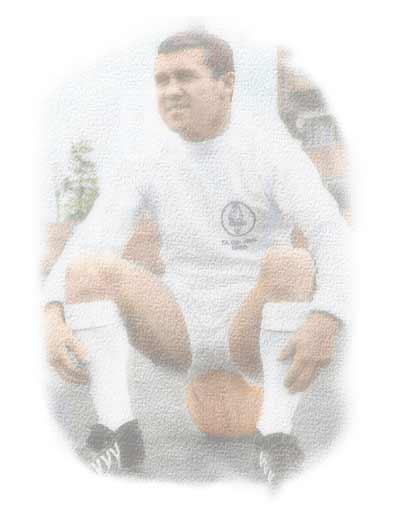

Don Revie might have been the

visionary architect behind Leeds United's rise to footballing eminence,

but it's a fair bet that had Revie not had the wit, foresight and downright

good fortune to bring Bobby Collins to Elland Road his grand design

would have been smothered at birth.

When Collins arrived at the club in March 1962, United were adrift

at the bottom of Division Two and staring the ignominy of the Third

Division starkly in the face. Five years later, as he departed for Bury,

Leeds were the most feared club in England and well on their way to

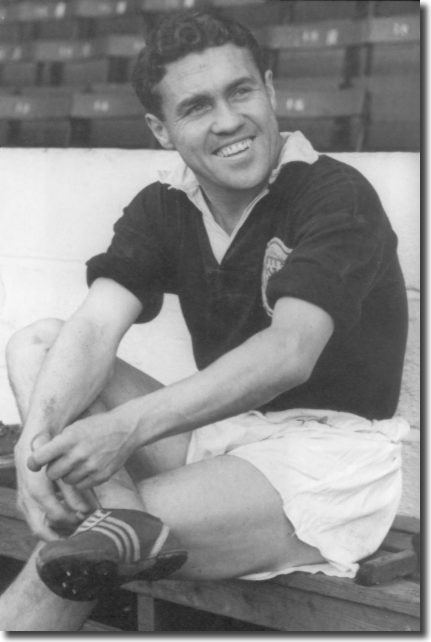

repeating the trick in Europe. The pocket-sized Napoleon - at his peak

he stood 5ft 4in, weighed 10 stone and wore size four boots - was almost

single-handedly responsible for the revival of a club that had been

going nowhere fast.

Revie was the brains behind the Leeds United resurrection, but Collins

was the heart and soul, the rousing, restless, ferocious spirit that made

sure the manager's game plan was translated into bloody action when the

players entered the arena, the Don's enforcer. Had the Scot not been there

to make the difference it is conceivable that Revie and United would have

faded into obscurity, and the point was never lost on the manager. Collins

was always one of his favourites and he never tired of singing his praises,

saying in The Leeds United Story:

'He's the perfect example of what we in the game call a professional's

professional. Bobby's aim was always to do things simply and quickly in

the field, he never tried to be too clever on the ball for the sake of

his own glory. I have never come across anyone with such a fierce will-to-win

and dedication to the game … Bobby regarded it as a personal insult to

be beaten - we had numerous kicking bouts when I played against him for

Manchester City! As manager of Leeds, I had been searching for some time

for a midfield general with the character and skill really to motivate

the team, and Bobby fitted the bill perfectly.'

Bobby Collins will always be remembered as a street fighter, a bruiser

capable of starting a scrap in a telephone box, and he refused to let

even the mightiest of opponents get one over on him. Rangers captain and

Scotland team mate George Young was at least ten inches taller than Collins,

but that did not deter Bobby, as recalled by his lifelong friend Tommy

McGrotty: 'Celtic supporters just loved his skill, power and commitment

and still talk about him today. One incident summed up Bobby for me. Celtic

were playing Rangers in a really tight match and Bobby went into a 50-50

ball with big George Young. George was slightly off balance and ended

up on the running track. You could see by the look on his face that he

was not pleased, but that was Bobby: total commitment and his efforts

will never be forgotten by Celtic fans.'

Jack Charlton: 'He was only a little guy

… but he was a very, very strong, skilful little player. But what marked

him out, and what made the difference to the Leeds sides he played in,

was his commitment to winning. He was so combative, he was like a little

flyweight boxer. He would kill his mother for a result!  He

introduced a sort of 'win at any cost' attitude into the team. Probably

because we had a very young side at the time, the other players were very

much influenced by his approach to the game.

He

introduced a sort of 'win at any cost' attitude into the team. Probably

because we had a very young side at the time, the other players were very

much influenced by his approach to the game.

'We went to stay the few days before the Cup final at a hotel near London,

the Selsdon Park in Crystal Palace. I remember playing a little five-a-side

game on the Friday. Norman Hunter volleyed the ball, and it hit Bobby

on the face, making his nose bleed a little. It was clearly an accident,

not deliberate or anything. Then the game restarted, and when Norman got

the ball Bobby just flew at him. It was obvious Bobby meant to do him

harm. I yelled, "Norman!" - and he looked up and turned just

as Bobby hit him in the middle with both feet. Bobby finished up on top

of Norman, punching him. I yanked him off, and I had to hold him at arms'

length because he started trying to whack me. "Come on, Bobby, calm

down," I said, "we've got a Cup final tomorrow." But that

was Bobby, you couldn't stop him when he got worked up.'

Rob Bagchi and Paul Rogerson, in The Unforgiven, described the

Scot as 'a man who exhibited grit to an almost psychopathic degree … Collins

knew that fear worked. If a player is intimidated, the likelihood is that

he will give his opponent more time - a footballer's most precious commodity.

Collins took it further than most would dare, far too far for some tastes,

but it was highly effective.'

Everton's Colin Harvey: 'If you stepped out of line in training, then

he would do you, no danger.'

Eddie Gray: 'Bobby was a strange person in some ways. He was very aggressive

and confrontational - even to his team mates or those who professed to

be close to him … Forget the fact that he was hardly built like a giant,

when he was riled - a situation that could be sparked by literally anything

- he was not a man to mess with. Bobby attributed this aspect of his game

to the general macho nature of professional football in his impressionable

development years. "It was a hard game in those days," he would

say, the sub text being that if players did not learn to look after themselves,

they would go under. I remember him talking about the first time he played

against Tommy Docherty when he was with Everton and Docherty was with

Arsenal. The Doc was one of his closest friends but, according to Bobby,

this counted for nothing during the game. When they challenged each other

for the ball near the touchline, Bobby found himself being propelled by

the Doc towards row Z of the stand. Thus Bobby was brought up in football

with what he described as a "kill or be killed" mentality.

'To an extent, the respect he had from the younger players at Leeds was

based not just on his skill and his record in the game, but also on the

fear factor. Whenever he instructed us to do something, we would jump.

As soon as you saw his finger go up, pointing at someone, you knew that

person was in trouble.

back to top

'I got on well with him although I was left in no doubt that this could

change dramatically if ever he had cause to feel that I had let him down.

One of my most embarrassing experiences at Leeds was when, at fifteen

or sixteen, I was in Bobby's team for pre-season training. There were

four teams in all, each comprising eight or ten players. Points were awarded

for our performances in various fitness exercises and the sessions were

extremely competitive. As I was regarded as one of the best runners at

the club, Bobby felt that victory for the team in the cross-country race

- and with it a score of 10 points - was virtually a foregone conclusion.

The only threat came from Jim Storrie, the Scottish

striker bought from Airdrie in 1962. Sure enough, half a mile from the

end, Jim and I were at the front; it was between him and me. I felt I

had loads of power in reserve but as I was thinking of unleashing it,

Jim said, "Eddie, we don't need to race. If we stay together, we

will both get ten points." I fell for it hook, line and sinker -

how naïve can you get? About 100 yards from the line, Jim, a real character

with a tremendous sense of humour, sprinted flat out to win. Bobby was

not amused. When he heard what had happened, he strode over to me and

gave me a cuff around the head, like a father admonishing a naughty child.

That tells you something about how much winning meant to him.'

Norman Hunter: 'In this game at Preston  I

was detailed to mark their big No 6 at set pieces - I didn't know his

name and I never did find out - and very early on he gave Bobby a kick.

Some time later they won a corner. Bobby came over to me and told me to

mark his man and leave the man I should have been marking to him.

I

was detailed to mark their big No 6 at set pieces - I didn't know his

name and I never did find out - and very early on he gave Bobby a kick.

Some time later they won a corner. Bobby came over to me and told me to

mark his man and leave the man I should have been marking to him.

'"But, Bobby, the Gaffer will give me a right rollicking if I don't

mark the man I'm supposed to mark," I protested, to which he replied,

"Do as I effing tell you. Take my man and I'll take yours."

'So I did. When the ball came over from the corner, Jack Charlton got

up and headed it away. Bobby leapt up, too, and launched himself with

everything he had at the big No 6, who went down as though he had been

pole axed - which I suppose in a way he had. Then Bobby was off like a

shot to the halfway line. You couldn't see him for dust. I was left standing

near the No 6 sprawled out on the ground and everyone thought I'd done

it. I took the blame while Bobby was inside the centre circle smirking.'

Collins could often be seen at Elland Road in the days when David O'Leary

managed one of the most exciting young teams in the country, and was particularly

taken with their approach of the period, seeing many similarities with

the brash young team he had led in the 1960s.

Rick Broadbent in Looking For Eric: 'It is the morning after Leeds'

1-0 victory over AS Roma in the fourth round of the UEFA Cup at Elland

Road … It was an intoxicating night in front of a packed house. Harry

Kewell scored the solitary goal and both Collins and I were there to witness

it. We also witnessed two Roma players being sent off for headbutts in

the dying moments after substitute Alan Smith successfully riled the Latin

defence. "I like Smithy," says Collins with a devilish flicker.

"He's got a lot of aggression and he puts himself about, which some

of the others don't. I like to see that. You've got to be able to play

as well, but a bit of both is ideal. I like this Leeds team a lot. The

only thing they don't do is pick up. Take last night. They knew Totti

was the danger man for Roma, but he had 30 yards of space in the middle

of the bloody field. Luckily, his shooting was awful. The thing you could

always say about the side I played in was that if we went a goal up then

that was that. Game over. We'd shut up shop. Some people didn't like it,

but we were good at it and successful. The good thing about the side they've

got down there now is they have a great attitude. They are all in it together.

It's all for one and one for all."'

There was much, much more to Bobby Collins, though, than mere thuggery

- he could not otherwise have sustained a playing career of almost 25

years. He was one of the finest British inside-forwards of the post war

era, a master of all the requisite arts - passing, shooting, ball control

and, of course, thunderous tackling. He marked out his own distinctive

chapter in football's history book, enjoying two decades at the very top

with Celtic, Everton and Leeds United, whilst also featuring in the 1958

World Cup finals with Scotland.

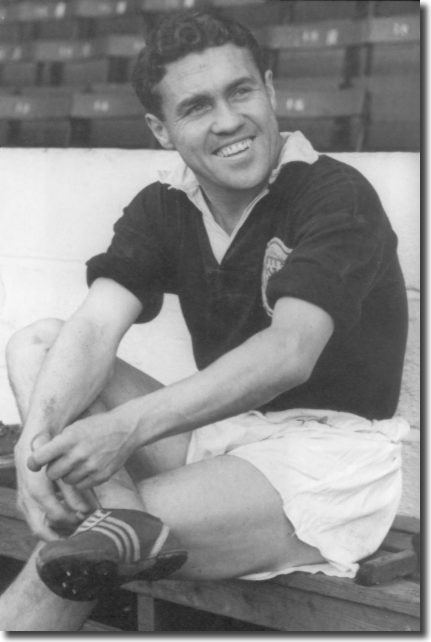

David Saffer wrote thus in the introduction to his biography of Collins:

'The Wee Barra, as he was affectionately dubbed by Celtic followers, endeared

himself to both players and supporters alike with his all action game.

A brilliant tactician and motivator, Bobby was a supreme passer of the

ball and possessed a thunderous strike, bamboozling many a goalkeeper

with his trademark banana shot. Though one of the smallest players around,

Bobby made his presence known in every game and never shirked a tackle.

His reputation preceded him, but there was little opponents could do.

Playing with and against the great stars of a golden era, Bobby held his

own against the elite.'

Everton's Roy Vernon: 'I have never played with a more talented, complete

inside-forward, a greater bundle of tricks and a more powerful powerhouse

than this diminutive Scot. Nor have I ever played against an inside-forward

of any other club who has left me with a feeling that here is somebody

even better than Collins. He is a buy in a lifetime. Where he gets his

boundless energy from I don't pretend to know. He never complains at hard

work, rather does he thrive on it. It is a gift that some players have,

which others cannot acquire if they play for years, the ability to take

the game by the scruff of the neck and play it at the tempo required.

There are times when games seem to go mad with players scurrying around

at breakneck speed, making their work much more difficult and the margin

for error ever so much greater. How useful it is at a time like this to

have a man, who almost imperceptibly applies the brake and becomes the

dictator.'

Eric Stanger on United's return to the First Division with victory against

Aston Villa in August 1964: 'Collins, still from the stand looking like

a schoolboy who has strayed into a grown ups' game, was as ever an inspiration

and a comfort to his colleagues. If there was a hole to be filled because

a man had either strayed or been drawn out of position, Collins filled

it. His capacity for work was enormous and he was desperately unlucky

not to score with one of his characteristic banana shots, which swerved

away to strike a post. It was Collins who bolstered the Leeds defence

in the first half when Reaney and Bell were a little

shaky and Charlton was often beaten in the air by Hateley.'

W Ian Guild, reporting the battle of Goodison

with Everton in November 1964 for the Yorkshire Post: 'Collins

stood out on his own as the complete footballer. His generalship and shrewd

distribution together with his willingness to work at both ends of the

field, guaranteed Leeds the lion's share of the ball.'

Those reports could have come from any period during Collins' illustrious

career. He was consistency personified and constantly centre stage, prompting,

cajoling and driving his men forward, never willing to accept anything

less than the very, very best.

He made his first class debut at 18  for

Celtic on 13 August 1949 against Old Firm rivals Rangers, and bowed out

as a 42-year-old for Oldham Athletic against Rochdale in April 1973, totting

up more than 800 appearances and 200 goals. With Celtic, he won a Scottish

League title in 1954 and the Scottish Cup in 1951. He led Leeds to the

Second Division title in 1964 and saw them finish Double runners up in

1965, when he was voted Footballer of the Year. He scored ten goals in

31 full internationals for Scotland, including one in three World Cup

appearances in Sweden in 1958.

for

Celtic on 13 August 1949 against Old Firm rivals Rangers, and bowed out

as a 42-year-old for Oldham Athletic against Rochdale in April 1973, totting

up more than 800 appearances and 200 goals. With Celtic, he won a Scottish

League title in 1954 and the Scottish Cup in 1951. He led Leeds to the

Second Division title in 1964 and saw them finish Double runners up in

1965, when he was voted Footballer of the Year. He scored ten goals in

31 full internationals for Scotland, including one in three World Cup

appearances in Sweden in 1958.

back to top

The playing career of Bobby Collins was an outstanding one, though he

never made it as a manager, operating in various roles at Oldham, Huddersfield,

Leeds, Hull, Barnsley and Blackpool. Despite this, Collins will always

be remembered as a remarkable footballer and a wonderful man.

For Leeds United, Bobby Collins was a mercurial catalyst, seizing control

of the club's immature and unfocused young troops and blending them into

a fighting force that carried all before them. He brought stature and

acted as a rallying point while the old lags were weeded out and then

he led his callow foot soldiers in a march on football's upper echelons.

Collins' arrival at Elland Road in 1962 allowed Don Revie to hang up

his boots and concentrate instead on shaping campaign plans. Relegation

to Division Three was headed off with a nine game unbeaten run that saw

just four goals conceded. Collins had achieved his first goal of making

United the toughest of nuts to crack.

1962 brought the short lived

return of John Charles to Elland Road before

Collins assumed the club captaincy that he was born for, driving his men

in pursuit of an unlikely and unsuccessful promotion challenge. The following

year Collins inspired a rough-hewn title triumph and United's return to

the First Division.

In his 34th year, the Scot enjoyed his

greatest ever season, elected Footballer of the Year and regaining

his international place as United launched a bracing assault on the twin

fronts of league and Cup. It was a year of near things, marking a personal

triumph for the midget Glaswegian, dubbed 'Shrinking Violent' by Rick

Broadbent. He had completed the job Don Revie had signed him for in double

quick time. He even had the chance to make his European debut before his

Leeds career was effectively ended on

Italian soil by a scything foul.

Showing his customary determination, the Scot recovered from a horrific

thigh fracture to return to United's first team, though he would never

again be the same player. He eventually moved on to Bury, but could look

back with satisfaction on a job well done.

It was not so much what Collins achieved with Leeds that was so remarkable,

but the way he did it. When, at 31, he was declared surplus to requirements

by Everton manager Harry Catterick, many good judges thought he was over

the hill, doomed to see out his dotage in the lower divisions. Legendary

Liverpool supremo Bill Shankly was narrowly beaten to Collins' signature

by Don Revie,  with

two of the best judges in football convinced there was life in the old

dog yet.

with

two of the best judges in football convinced there was life in the old

dog yet.

Neither of them, though, could have anticipated the impact the old master

was to have - the phrase 'Indian summer' could have been coined for Bobby

Collins. The autumn of his career was a glorious one indeed.

Celtic forward Bertie Auld followed Collins into the Glasgow team's ranks

in the late Fifties and offered this affectionate tribute in his foreword

to The Wee Barra:

"Bobby Collins was a model footballer and a major influence on me during

my career. He was in the Celtic team when I broke into first team football

and was a member of the Scotland XI when I won my first cap against Holland.

'Bobby made me feel so welcome at Celtic from the start. I remember him

giving me his Adidas boots from the 1958 World Cup finals. They were slightly

big for him at the time but they were my first major manufacturer's pair.

I was the envy of all the younger players breaking through in the squad!

Bobby was great with the young kids at Celtic. In the late Fifties there

were no full time coaches as such, we had a manager who selected the team,

although he was influenced by the chairman, and we had a physio. The coaches

were the more experienced players. The club had a particular dress code

and Bobby looked the part both on and off the pitch. He was always immaculately

dressed and a model professional. Everyone admired him.

'We got on really well both on and off the park. Bobby made you feel

so important because he realised that the reserves today were the first

team players tomorrow. A number of us at the club, Billy McNeill, Steve

Chalmers and myself, went on to become part of the Lisbon Lions. Others

such as Pat Crerand starred at Manchester United. Bobby helped us all.

'On the park, if things were going wrong, he was always encouraging and

a great source of inspiration. It was brilliant being in the same team

as Bobby, but a nightmare for opponents! He never stopped you from expressing

yourself, and if you had a bad game or made a mistake he would be the

first to offer alternatives. You could not help but admire him.

'Bobby was a winner. He was also a manager's dream because he could play

in various positions, but in my opinion he was devastating at inside-right.

Bobby was physical and a wee bit robust but he was not a dirty player.

His all action game meant that he picked up injuries that would have finished

most players, but Bobby always came back stronger, His strength of character

was astonishing.

'There were so many games when Bobby had a major impact. I remember when

Celtic won 4-1 at Rangers in a Cup match. Bobby controlled the game from

start to finish; he was immense, and then in my first international against

Holland he was again outstanding. One other game that has to be recalled

was again against Rangers, this time in the 1957 League Cup final, when

we won 7-1. Unfortunately for me after playing in all the earlier rounds,

I missed out on that famous occasion and had to play in a reserve match

against Queen of the South, but I've seen a film of the game and it was

one of those days when everything went right and Bobby was at the hub

of everything positive. He was incredible.

'Whenever Celtic supporters recall great stars from the Fifties, they

nominate the Wee Barra. The term "legend" is used far too much

these days, but not in the case of Bobby Collins, both as a team player

and as an individual. His name is up there with the very best, and I know

it's the same at both Everton and Leeds United where he was just as sensational.

'Bobby Collins could have graced a team in any era; he was one of British

football's greatest stars.'

Part 2 Home grown hero - Part

3 From Sweden to Liverpool - Part 4 Back from

the dead - Part 5 End of the line

back to top

Part 2 Home grown hero - Part

3 From Sweden to Liverpool - Part 4 Back from

the dead - Part 5 End of the line

Part 2 Home grown hero - Part

3 From Sweden to Liverpool - Part 4 Back from

the dead - Part 5 End of the line

He

introduced a sort of 'win at any cost' attitude into the team. Probably

because we had a very young side at the time, the other players were very

much influenced by his approach to the game.

He

introduced a sort of 'win at any cost' attitude into the team. Probably

because we had a very young side at the time, the other players were very

much influenced by his approach to the game. I

was detailed to mark their big No 6 at set pieces - I didn't know his

name and I never did find out - and very early on he gave Bobby a kick.

Some time later they won a corner. Bobby came over to me and told me to

mark his man and leave the man I should have been marking to him.

I

was detailed to mark their big No 6 at set pieces - I didn't know his

name and I never did find out - and very early on he gave Bobby a kick.

Some time later they won a corner. Bobby came over to me and told me to

mark his man and leave the man I should have been marking to him. for

Celtic on 13 August 1949 against Old Firm rivals Rangers, and bowed out

as a 42-year-old for Oldham Athletic against Rochdale in April 1973, totting

up more than 800 appearances and 200 goals. With Celtic, he won a Scottish

League title in 1954 and the Scottish Cup in 1951. He led Leeds to the

Second Division title in 1964 and saw them finish Double runners up in

1965, when he was voted Footballer of the Year. He scored ten goals in

31 full internationals for Scotland, including one in three World Cup

appearances in Sweden in 1958.

for

Celtic on 13 August 1949 against Old Firm rivals Rangers, and bowed out

as a 42-year-old for Oldham Athletic against Rochdale in April 1973, totting

up more than 800 appearances and 200 goals. With Celtic, he won a Scottish

League title in 1954 and the Scottish Cup in 1951. He led Leeds to the

Second Division title in 1964 and saw them finish Double runners up in

1965, when he was voted Footballer of the Year. He scored ten goals in

31 full internationals for Scotland, including one in three World Cup

appearances in Sweden in 1958. with

two of the best judges in football convinced there was life in the old

dog yet.

with

two of the best judges in football convinced there was life in the old

dog yet.