|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inter Cities Fairs Cup First Round Second Leg - Stadio Comunale, Turin - 26,000

Scorers: None - Leeds United won 2-1 on aggregate

Torino: Vieri, Poletti, Fossati, Puja, Teneggi, Ferretti, Meroni, Ferrini, Orlando, Pestrin, Simoni

Leeds United: Sprake, Reaney, Madeley, Bremner, Charlton, Hunter, Giles, Lorimer, Peacock, Collins, Cooper

In November 1963, Leeds United chairman Harry Reynolds gushed enthusiastically:

'We not only want to be one of the best clubs in England, but in Europe.

We want to be in that Super League if it comes. We At the time, Reynolds' words sounded like the fanatical ravings of an

over enthusiastic geriatric. By the autumn of 1965, though, United were

indeed contemplating their European debut after finishing

runners up in both Cup and League. The season had ended disappointingly,

but coming second in the title race brought the consolation of entry into

the Inter Cities Fairs Cup tournament for 1965/66. The competition was almost as old as the European Cup, although it had

enjoyed a less straightforward history. According to the Encyclopaedia

of British Football, 'In 1950 Ernst Thommen, then vice-president of

FIFA, proposed the establishment of an international competition between

clubs, or city-wide teams, from cities which hosted industrial fairs.

His idea was to give a competitive edge to friendly matches played between

teams during trade fairs. Following a meeting in Basle in 1955 the first

competition eventually got under way in June 1955, with a match between

Basle and London. 'The regulations for the competition were drafted by Sir Stanley Rous.

Essentially these were that only one team from a city could enter, that

matches would coincide with the cities' trade fair, and that the competition

would be called the International Industrial Inter-Cities Fairs Cup. The

trophy was called the Noel Beard trophy. 'Two English teams entered - London, which was made up of the 11 professional

teams playing in the capital, and Birmingham, which was represented by

Birmingham City. The first competition was organised into four mini leagues

with the four group winners qualifying for the semi final. The first competition

was scheduled to last two years, but because of fixture congestion it

took three years to complete. 'The first final was a two-legged affair between London and Barcelona.

Following a 2-2 draw in the first leg, Barcelona won the second leg 6-0

at the Nou Camp in front of 70,000 fans. 'The second Fairs Cup took two years to complete, 1958-60, but henceforth

it would be an annual tournament running parallel with the European Cup

and the newly established Cup Winners' Cup.' Everyone associated with Elland Road was highly delighted when United's

nomination as one of England's representatives in 1965/66 was confirmed.

They were equally pleased with the news that they would be pitted against

Torino, one of Italy's crack teams, in the first round. The Turin club had a long and rich tradition in Italian football, but

were still rebuilding after a tragic end to a glorious period in their

history. A legendary Torino team perished in a terrible air crash in 1949

when their plane hit the church of Superga in the hills over Turin. In

all, 31 people died, on the way back from Jose Ferreira's farewell match

in Lisbon. The crash was the biggest tragedy in Italian sports history,

claiming the lives of a team that had won the Serie A title for four years

in a row, along with the last championship before the war. The club struggled

to recover from the blow and were relegated in 1959 after a decade of

mid table finishes, though they returned at the first attempt after winning

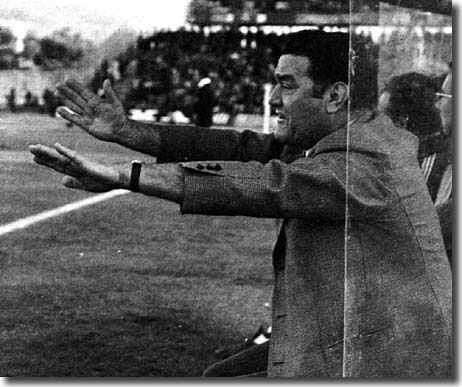

the Serie B title. The Italians were under new management: the redoubtable Nereo Rocco had

Rocco was a renowned coach, the inventor of the legendary Catenaccio

formation. The Guardian: 'Catenaccio - Italian for "doorbolt"

- is a defensive style of football created by Padova coach Nereo Rocco

in the early 1950s. It takes the form of a diamond-shaped defence, in

which a midfield "libero" (free man) is accommodated. Rocco

introduced the system to counter the goalscoring of rival Italian clubs

and, once it proved successful, it was used by AC Milan, who won the European

Cup playing Catenaccio in 1963 and 1969.' Rocco enjoyed a stormy relationship with ace goalscorer Jimmy Greaves,

when the two were together at Milan. David Winner describes the episode in Those Feet: A Sensual History

of English Football: 'Under Rocco at AC Milan, Greaves felt "like

a little boy lost". He thought the Italian game "spiteful and

vicious", detested every second of his fourteen-game, nine-goal career

and blamed the experience for turning him into an alcoholic. Years later

he described Rocco as being like Mario Puzo's Godfather and claimed: "The

Italian press murdered me. They could not have done a better assassination

job had they been given a contract by the Mafia." Greaves was paid

a fortune, but lost most of his money to fines as Rocco vainly attempted

to get him to observe the strict Italian codes of sporting behaviour:

no booze, no sex before matches, spartan training camps and obedience

to the coach at all times. Greaves refused to be, as he saw it, "just

another sheep in his flock of highly paid but unhappy footballers".

Rocco despaired of Greaves' late night carousing, one night even nailing

his hotel door shut with planks of wood. It didn't work; Greaves climbed

out of his window three storeys up and crept along a narrow ledge while

his manager waited downstairs watching the main exit.' Torino had already dispensed with two British imports, Denis Law and

Joe Baker, in the summer of 1962, though the goals of another Brit, Gerry

Hitchens, took Rocco's men to third spot in Serie A behind the two Milan

clubs in 1965. It was Torino's best finish since Superga and they also

reached the semi final of the Cup Winners' Cup before losing to 1860 Munich

- they were hot favourites to beat Leeds when the draw was announced. United manager Don Revie flew to

Italy with chief coach Syd Owen to watch Torino play a goalless draw at

home to Cagliari in the week before the tie and commented: "They are a

hard, strong side and will be difficult to beat. Their defence is very

tight and they have several cracking good players. They will be hard to

open out." For all United's lack of familiarity with the subtleties of Continental

competition, the first leg at Elland Road on September 29 saw United take

to the new challenge like a duck to water. Revie sent his forwards out

in mixed up shirt numbers to confuse the Torino marking plan (7 - Peacock,

8 - Collins, 9 - Cooper, 10 - Lorimer, 11 - Giles). Phil Brown in the

Yorkshire Evening Post: 'That little ruse of Mr Revie's nearly

nicked a goal while Torino were sorting it out, but, like the very good

professionals they are, Torino held.' The ruse was quickly rumbled by

the Italians, who resisted United's opening lunges thanks mainly to solid

performances by goalkeeper Lido Vieri and centre-half George Puja. However, they could not hold out for long. Billy Bremner ('the best player

on the field' according to Phil Brown of the Yorkshire Evening Post)

scored the opening goal of the game and United's first in European football

after 25 minutes with a speculative curling shot from the left wing: 'Vieri

could only juggle it into his own net. The crowd were ecstatic and the

goalkeeper surveyed the muddy turf no doubt wishing that it would open

and swallow him.' The Whites came close to increasing their lead as the

interval neared, but it was the 48th minute before Alan

Peacock's header crowned a decent passing move and doubled the advantage.

Later Peacock had a goal disallowed with the referee ruling the ball had

not entered the goal, 'though the centre-forward was afterwards to claim

the ball was a good 18 inches over the line'. Opting to go for a killer third goal rather than sitting on a decisive

2-0 lead, United's inexperience betrayed them. They left themselves exposed

late on and Torino centre-forward Orlando pulled one goal back 12 minutes

from time. Nevertheless, Leeds had played astonishingly well against outstanding

opponents. They earned high praise, with Italian sports writers describing

United as 'the strongest and best team in Britain'. Don Revie was unstinting

in his praise, telling Phil Brown: 'The team has never played better since

I became manager at Elland Road. They were splendid in their skill and

determination, and they gave the lot and a bit more in effort. They had

not a thing left when they came in. How they maintained the pace on a

poor night and soft pitch I do not know. I am the proudest manager in

Britain today. Yet when I went with them into the dressing room after

the game they were so grieved at having won only 2-1 that Bobby

Collins said to me: "Boss, just listen to them! You would think

we had lost 3-1!" I would like respectfully to remind our critics

and our doubters that seven of last night's United side were only 22 or

under. The experience they gained last night against a very good team

under a very good manager should be most valuable to them. But above all

my own feeling is of pride in them after this Continental football baptism.' Nereo Rocco said: 'Leeds were a fine team, but they have a singly magnificent

crowd. They were splendidly fair to us, despite the importance of the

occasion to both teams, and the fire in the play. I must thank them and

hope that our crowd is as fair to their team next Wednesday. Your crowd

The away goals rule had yet to be introduced so it would take a victory

by two clear goals in Turin to put the Italians through, but most independent

experts believed Torino's greater experience would be decisive. Revie

saw things differently: 'We are one of the hardest sides to beat away,

and we will be trying for a quick goal to surprise Torino.' Leeds, enjoying a weekend's rest before the game with England in Home

Championship action against Wales, fielded the same eleven that beat Blackburn

3-0 on 25 September and saw the Italians off in the first leg. Terry Cooper

continued to deputise for the injured Albert

Johanneson, while youngsters Paul Madeley and Peter Lorimer demonstrated

the worth of Revie's youth policy. Leading the attack was the in form

Alan Peacock, fresh from restoration to the England team after three years'

absence. Along with Jack Charlton

and Gary Sprake, Peacock had played in the goalless draw between England

and the Welsh in Cardiff. In contrast to United's settled roll call, the Italians rang the changes

for the match in Turin, with Fossati, Teneggi and Meroni coming in for

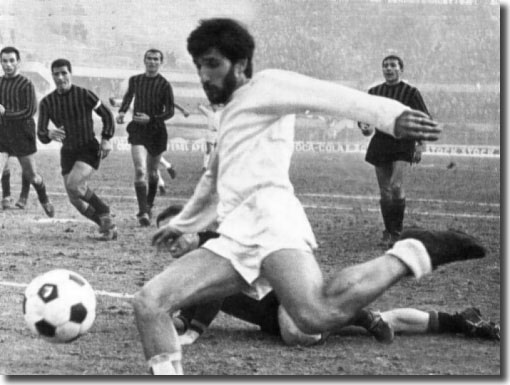

Rosato, Bolchi and Schulz. The return of Gigi Meroni on the right flank

was particularly crucial. The 22-year-old, nicknamed La Farfalla Granata,

the 'Grenade Butterfly', was a Continental equivalent of George Best.

Torino's record buy (£130,000 from Genoa in 1964), he was a prodigious

talent, 'a first-rate dribbler and expert at nutmegging his opponents'. Meroni, all 'elusive running', and George Ferrini, 'a strong and incisive

player', were prominent as Torino took the game to United in the early

stages in the Stadio Communale. Leeds, though, manufactured the first

chance of the game. Jack Charlton: 'We could have been a goal up after only thirty seconds,

but Peter Lorimer's shot was clutched safely by goalkeeper Vieri; then

Vieri clawed a header from me as the ball was sneaking under the bar;

and Norman Hunter, put through after a great Lorimer run, missed his kick

in front of an open goal.' The openings for United were scarce as they devoted their first half

for the most part to maintaining their slim advantage. Peacock was left

to plough a lone furrow up front with his fellow forwards supplementing

a packed midfield. Phil Brown in the Yorkshire Evening Post: 'Charlton

held the middle from the first minute and Bremner and Hunter covered acres

on their flanks, challenging, intercepting, tackling, forcing men to part

with the ball unsuitably and taking all the danger out of Torino's attack.

But the half-back line even in top form still needed help, for Torino

sometimes attacked with 10 men in the second half, and they got it. Giles,

Lorimer, Peacock and Cooper all came back in defence, with Collins likewise

while he was on, and all did their share.' The overlapping full-backs, Reaney and Madeley, often presented the greatest

threat, freed by the smart passing of Giles to counter swiftly from defence.

Eric Stanger wrote in the Yorkshire Post: 'Right from the start

Torino made the running to wipe out the goal lead which Leeds had from

the first leg, but their neat progressive football was countered by the

immaculate Leeds defence. Leeds, indeed, came nearer to scoring with their

quick breakouts.' In the last five minutes of the half, United had a decent spell, prompted

by skipper Bobby Collins. He collected smartly from Peacock and sent in

a shot which skimmed a post, before dispossessing Ferrini with a wonderful

tackle and swiftly turning deep defence into dangerous attack. Suitably revived by their captain's example, Leeds took their break in

good heart with the first challenge successfully negotiated. They had

been outmanoeuvred and penned in, but had proven their defensive solidarity.

The players' mood was buoyant, although any degree of complacency was

dissipated five minutes after the resumption. Bobby Collins had been United's fulcrum since his arrival in 1962, and

in Turin he was again the heartbeat of a fiercely defiant display. Unfortunately,

he would not see out the hour. Norman Hunter: 'I can still remember the tackle that put him out of the

game and left us to battle for forty-five minutes with only ten men. Bobby

and I were both well up the field when I saw a big defender coming towards

him. Bobby was extremely quick over five to ten yards and he knocked the

ball forward and accelerated after it but the big guy didn't pull up.

He kept on running and his knee went right into Bobby's thigh. When I

got to Bobby, his leg was waving around at the top because the bone was

snapped high up the leg. It was horrendous.' Jack Charlton: 'I remember it very vividly - Bobby was lying there, the

referee wanted to move him off the park, and the Turin players were trying

to bundle him off. I wouldn't let them move him; I knew that if Eric Stanger: 'For a few minutes tempers flared in a game which up to

that point had been cleanly fought. Meroni kicked Bremner, Giles and Pestrin

clashed, but Mr L Roomer, the Dutch referee, kept a firm hand and very

soon had things under control again.' Billy Bremner, for whom Collins was an idol, was incensed and the guilty

man, left-back Fabrizio Poletti, needed no interpreter as the Scot bitterly

promised, 'I'll kill you for this.' The mythology surrounding the game paints Poletti as some kind of cold

blooded assassin, but at the time there was a more restrained reaction,

as typified by Phil Brown: 'Italian journalists assured me that Poletti

has no name for fouls, and indeed it was the only one he committed in

the game. He was a clean player at Leeds last week, too. But in the fever

heat of the tie I think Poletti lost his head. He is only 22, and he has

been to see Collins to apologise deeply.' Poletti seemed genuinely remorseful, saying, 'It happened so quickly.

He was going so fast. It has been a shock to me, and I am sincerely sorry.' After the dust had cleared, United were left to withstand 40 minutes

of all out pressure by one of Europe's best attacks with just ten men.

Substitutes had been introduced for Football League games at the start

of the season, but were still some way off for European competition. What

followed was a remarkable performance, quite possibly the greatest rearguard

action that Don Revie's Leeds United ever fought. In the first period they had played disciplined, controlled football,

laying down an ironclad wall across the pitch, denying their classy opponents

time and space and harrying them out of their poise. The absence of Collins

seemed merely to reinforce the players' spirit. Eric Stanger: 'Now came Leeds United's finest half-hour. Every man gritted

his teeth and shouldered the extra burden imposed on him by the loss of

Collins. Torino grew more and more worried, as they found out they just

could not shake off these brave fighters. Their football became ragged.

The crowd whistled in disapproval as the Leeds tentacles gripped tighter

and tighter, with every man refusing to give an inch or admit defeat.' For all their ability, the Italians could find no chinks in the United

armour. Gary Sprake made a couple of decent saves, but for the most part

the men in front of him, working like drones, shielded him from danger. The Italians' football grew increasingly frenetic as the end approached,

and United came close to snatching a remarkable victory at the death when

Bremner burst clear from midfield, beat the defence and saw The home crowd turned on their team during the final quarter. The game

ended in a 'gale of whistles of contempt and the fans lit 20 bonfires

on the terraces at the end - another gesture of thumbs down. United left

the field to a round of applause and it was nice to see them turn and

see 200 odd Leeds supporters who were there, for those supporters had

let the Italians hear "Leeds Leeds Leeds" and "Ilkla Moor"

in grand style.' The game finished without a goal, leaving United in the second round

by virtue of the 2-1 aggregate score. It was a memorable evening, and the triumph in adversity proved a turning

point in the history of Leeds United. Their football, for so long reviled

in England, seemed perfectly designed for the European game and they were

generously praised by the Italian press. 'Leeds know how to defend themselves - Torino eliminated' was the headline

in Milan's Gazzeta Della Sport. The piece ran on: 'Leeds built

its remarkable play on the Bremner-Collins diagonal - at least until the

game turned into a brawl - without giving up attack in advance, but with

vigorous defensive tactics, continuously dotted by violent counter attacks.

What we saw was once again a very fine team, entirely worthy of continuing

its march in the Cup. 'After their well deserved win in Britain, they succeeded in controlling

a Torino that was in fine shape and determined to play to the end. And

in the second half Leeds, with only 10 men, succeeded in resisting the

forcing play of their opponents. Left without schemer Collins, the Leeds

players turned into defenders, forming a barrier in a strong and energetic

way but without any fouling.' Vittorio Pozzo, who coached the Italian national team to World Cup victory

in 1934 and 1938, wrote in Turin's La Stampa: 'This was the fastest game for a long time in Italy. Leeds are a robust,

determined team, full of willpower and with exceptional ability. This

team had said a word about British soccer which for years had not been

heard and which convinced the crowd. The whole team seemed to be spurred

by fire, but the work performed by inside-left Collins and right-half

Bremner will not be forgotten soon by those who watched the game.' For Bobby Collins, however, there was only the fear that, as he neared

35, his playing career might be at an end: 'The pain was agonising and

I knew immediately that my leg was badly broken. Les Cocker came on and

supervised as I was carried off to be taken to hospital. Willie

Bell, who had been in the squad but was watching in the stadium, escorted

me and helped keep the stretcher and my leg steady. 'The only fortunate thing, though I didn't realise it at the time, was

that I was seen at a local hospital that 'The Professor assessed the injury and operated immediately. When I came

round, he told me that he had reset my

shattered thigh bone with a fifteen inch pin and was confident that I

would play again with the pin inside, which was very reassuring. 'Leeds flew Beryl and Robert out to be with me, and throughout my two

week stay at the hospital, I had plenty of visitors, including the entire

Torino side. Poletti was particularly apologetic, but it didn't stop him

injuring another player in the next match! 'The flight home wasn't the most comfortable as I had a special cast

devised only for reclining seats, but they didn't recline. 'Back home I immediately began my rehabilitation under Les (Cocker) and

Doc Adams. The pin was hollow, which enabled it to stay in my leg as I

regained fitness. It stayed there for two years, before Mr Archie McDougall,

an orthopaedic surgeon in Glasgow, removed it. The injury effectively

ended my career at Leeds.' Shorn of his pocket general, Don Revie gave Irishman Johnny Giles his

head as play maker, thereby creating a midfield partnership with Billy

Bremner that would inspire United's success over the decade that followed.

Revie secured the services of Huddersfield

Town's England winger Mike O'Grady to fill Giles' berth on the flank

and saw his men emerge from the shadow of Bobby Collins to become a truly

great team. The injury was not quite the end of the road for Collins, and astonishingly

he was back for the season's climax, a draw with Manchester United that

secured runners-up spot for a second successive year. The return was a short one, however. Collins made the United team for

the start of the next campaign, but joined Bury on a free transfer in

February 1967, marking the end of a remarkable liaison between player

and club. It had been a match made in heaven, although many of Collins'

opponents might have muttered that it was forged somewhere less pleasant! Billy Bremner: 'I learned many great lessons from Bobby Collins, not

the least being able to take the knocks as well as hand them out and always

play the game as a man. They say that one man doesn't make a team - but

Bobby Collins came nearer to doing it than anyone else I have ever seen

on a football field.'  do

not just wish to get into the First Division but to win it and get into

the European Cup.'

do

not just wish to get into the First Division but to win it and get into

the European Cup.' deserted

AC Milan after leading them to a European Cup triumph in 1963 and had

taken up the reins at Torino.

deserted

AC Milan after leading them to a European Cup triumph in 1963 and had

taken up the reins at Torino. has

a splendid team. They should have scored four or five goals in the first

half.' Some of the wily Italian's comments were made purely for the benefit

of public consumption, and he was confident of recovering the tie at home.

has

a splendid team. They should have scored four or five goals in the first

half.' Some of the wily Italian's comments were made purely for the benefit

of public consumption, and he was confident of recovering the tie at home. Bobby

Collins wouldn't get up, he must have something broken. I stood over him,

whacking one Italian and punching another to keep them back, until eventually

the referee realised that Bobby must be seriously hurt and called for

a stretcher.'

Bobby

Collins wouldn't get up, he must have something broken. I stood over him,

whacking one Italian and punching another to keep them back, until eventually

the referee realised that Bobby must be seriously hurt and called for

a stretcher.' his shot scrape

the post.

his shot scrape

the post. specialised in repairing shattered

limbs. Surrounded by mountains, they had gained a reputation in this field,

having dealt with many ski and mountaineering casualties, They had perfected

techniques for all kinds of fractures. The medical team was headed by

a world-renowned surgeon, Professor Re. I could not have been in better

hands.

specialised in repairing shattered

limbs. Surrounded by mountains, they had gained a reputation in this field,

having dealt with many ski and mountaineering casualties, They had perfected

techniques for all kinds of fractures. The medical team was headed by

a world-renowned surgeon, Professor Re. I could not have been in better

hands.