|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

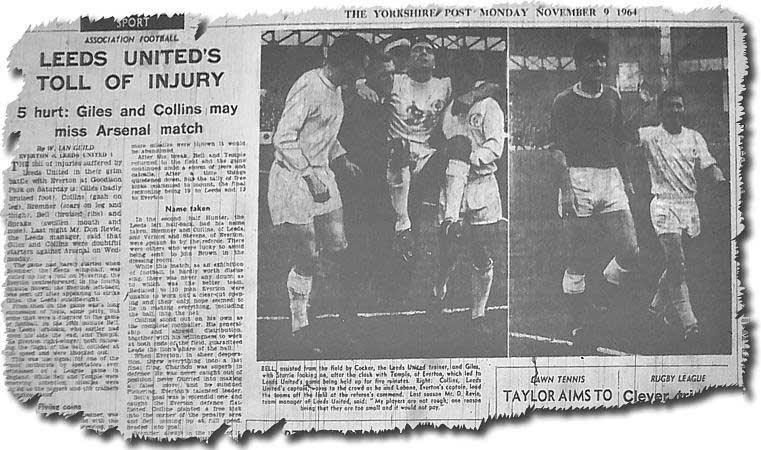

First Division - Goodison Park - 43,605

Scorers: Bell

Everton: Rankin, Rees, Brown, Gabriel, Labone, Stevens, Temple, Young, Pickering, Vernon, Morrissey

Leeds United: Sprake, Reaney, Bell, Bremner, Charlton, Hunter, Giles, Storrie, Belfitt, Collins, Johanneson

Certainly, the reputation of the club was well established by the end

of 1964. During October, the Elland Road crowd had struck up with a chant

of 'Dirty Tottenham … Dirty Tottenham', ironically mocking the castigation

that United regularly suffered, as Spurs had four players booked in a

3-1 defeat. Whatever the truth, there was one specific day in the late autumn of

1964 that ranks very prominently in the development of the legend - Leeds

United's clash with Everton on 7 November 1964 has gone down in the annals

of English football as one of its most notorious confrontations. It took

both sides to generate the heat that ruined the day, but it certainly

cemented the reputation of the Whites for provoking controversy and rancour. It's a moot point as to whether Don Revie set out with the deliberate

intention of his men kicking their way to success. The man himself always

strenuously denied any such thing, choosing instead to lay the blame at

the door of opponents, referees, commentators … anybody outside the confines

of Elland Road would do, as long as it wasn't his charges who took the

blame. However, there are simply too many examples of the Yorkshiremen

being involved in appalling scenes for all his protestations of innocence

to carry much credibility. Jack Charlton provided a telling

hint of the Elland Road approach, whilst denouncing it, in his 1996 autobiography:

'We made a lot of enemies in that 1964/65 season. I remember lying on

the treatment table in the Leeds dressing room with one of the young lads,

Jimmy Lumsden. He was talking about a reserves match the night before,

and he told me that he had gone in over the top of the ball to a guy who

had then had to be taken off. "I gave him a beauty," Jimmy said.

Don murmured something approvingly. "Jimmy," I told him, "Jimmy,

you live by the sword, you die by the sword. That guy might some day play

against you again, he will remember you and he might just go over the

top to you when you're not expecting it. You might finish up breaking

your leg."' Irish playmaker Johnny Giles earned himself a darker name after his arrival

at Elland Road. He was unequivocal about the reality of the professional

game: 'You had to establish a reputation that would make people think

twice about messing with you … I have certainly done things on the football

field then that I am embarrassed about now, but one has to put them into

the football climate that existed then. It was a different game then,

much more physical than it is today - vicious even - and people like Bobby

Collins and myself were targets … Now you either took it or you responded

to it, and Bobby and I responded to it … you had to get respect in the

sense that people could not clog you without knowing that they would be

clogged back. People might say, 'Oh, that's not right - it's not sporting,'

but that's the way it was, a fact of life.' The jutting-out chins, brash arrogance and shameless attitude of United's

players brought out the worst in others, provoking them to outdo Leeds

at their own game. As often as not, uptight opponents would forget to

play football in their eagerness to fight fire with fire and that usually

spelled their downfall: United had gained the upper hand, earned the right

to dictate terms and usually finished off their opponents with equal measures

of skill and brutality. It mattered not which weapon was required, Revie's

men were as adept with both bludgeon and rapier. The mood in the autumn of 1964, as Leeds made their way in football's

top flight, was uncompromising. The paranoid siege mentality that so often

characterised Revie as a manger came spilling over when he heard the news

that the Football Association had named his beloved players as 'the dirtiest

side in the country'. The FA were determined to take firm action against

the game's worsening discipline and the Association's official journal,

the FA News, carried an article in August examining the disciplinary

records of its membership. Leeds United were highlighted as the Football

League club with the worst record for players cautioned, censured, fined

or suspended. United reacted angrily to the article, pointing out that it was not the

first team, but the junior sides, that were responsible for the bulk of

the numbers. Revie told Phil Brown of the Yorkshire Evening Post:

'We did not have a single first team player sent off last season and we

had only one suspended, Billy Bremner, after a series of cautions, which

is a lot more than many clubs can say. The majority of our offences were

committed by junior second team players or boys. For that I blame the

tension which permeated the whole club in the long and hard drive for

promotion in a very hot Second Division. It was a time of very great strain

for us all, and the club spirit being as wholehearted as it is from top

to bottom.' United prepared a formal response to the FA, warning ominously: 'We Revie feared an over reaction from the teams that United played. Certainly,

that was how it worked out in the fierce clash at Goodison Park. Leeds were the form team of the two, sitting fourth in the table, on

the back of four straight victories. Everton were eighth, without a win

in a month. They remained a class act, though, and were eager to put United

in their place. John Moores, after making a fortune with the Littlewoods organisation,

took over as chairman of the Merseyside club in 1958 and financed their

rebuilding plans under new manager Harry Catterick, appointed in 1961.

The Toffeemen won their first title for 24 years in 1963, twelve months

after Bobby Collins forsook Goodison for Elland Road. They were now one

of the country's finest teams, boasting such talent as centre-half Brian

Labone, Dennis Stevens (who took Collins' place in the team after arriving

from Bolton), Scottish international right-half Jimmy Gabriel, goalscorer

Roy Vernon and the fans' favourite, 'The Golden Vision', Alex Young. Everton had a number of players unavailable for the game, including Scott,

classy utility player Brian Harris and Scottish international full-back

Alex Parker. United had their own injury worries and former England centre-forward

Alan Peacock had missed the entire

season. Young Rod Belfitt, just turned

19, continued to deputise up front, scoring three goals in six appearances

prior to the game. Everton's players expected a battle and were patently aware of United's

reputation. Indeed, only those cast adrift in the Arctic for the preceding

two years could have been unaware of their record - the autumn had seen

Leeds implicated in several highly controversial moments. Richard Ulyatt of the Yorkshire Post: 'On 12 September, Gibson

of Leicester City was sent off the field when playing on Leeds United's

ground … On 17 October, four Tottenham players had their names taken by

the referee … On 31 October, Badger, the Sheffield United full-back, was

sent off … Sheffield were so incensed that their programme comments for

last Saturday's home match against Chelsea included passages they may

eventually regret. It described the Leeds match as a "travesty of

soccer". It was said "Badger was fouled and needlessly hacked"

(a free kick was awarded against Sheffield, not Leeds) and it was added:"'It

is significant that this incident was not the only flare up there has

been at Elland Road in recent weeks. Further comment is unnecessary."

That was comment by a club not the press.' The atmosphere was tense in Liverpool that day. Goodison Park has never

been exactly placid; Jack Charlton rated the Everton crowd as 'the worst

before which I have ever played … there always seems to be a threatening

attitude, a vicious undertone to their remarks.' United had tangled with Everton in the FA Cup nine months earlier, and

had taken them to a replay before going out in a ferocious clash. For

many of his former team mates, memories of Bobby Collins' readiness to

take liberties were still fresh, and they awaited Leeds United with a

mixture of anxiety and antagonism. Life with the Yorkshiremen always carried

menacing undertones and Everton were on a short fuse, fully wound up and

all ready to go. The game was only seconds old when Everton centre-forward Fred Pickering

was fouled Rob Bagchi and Paul Rogerson: 'Jack Archer of The People called

it a "spine-chilling" game, one littered with a long procession

of fouls, the type Charlton described as "sneaky things - going in

over the top, boots hanging in late". In only the fourth minute Giles

and Sandy Brown, the Everton left-back, had jumped into a tackle just

outside the Everton penalty area. Brown, incensed by the vigour of Giles'

challenge and subsequently complaining of "stud marks in the chest",

got up and threw a left hander at Giles and was predictably sent off.

From then on the frenzied atmosphere saw both sets of players flying into

tackles with the crowd baying for retribution.' Some extraordinary things went on that afternoon and there were no prisoners

taken by either side. The temperature climbed in the white-hot cauldron

of Goodison - professional footballers forgot this was a sport and instead

pitched themselves into fully fledged combat. Somewhere amidst the fearsome conflagration, though, there was actually

a little football being played and after fifteen minutes Leeds took a

priceless lead. They won a free kick far out on the right wing. Bobby

Collins swung the ball high into the heart of the Everton goal area. Full-back

Willie Bell came running up at speed

from far out to find space in the box and met the ball perfectly. His

header flashed into the net with the home defence helpless. It was a well-worked

goal and evidence of the defender's willingness to supplement the attack. The home crowd had been incensed by Brown's dismissal and now they became

uncontrollable. Any Leeds player who was foolish enough to come within

throwing distance ran the risk of being struck by missiles - for Gary

Sprake there was no hiding place as his goal was pelted mercilessly by

a hail of coins throughout the game. Things came to a head after 36 minutes. Bell and Everton right winger

Derek Temple were following the flight of the ball and seemingly unaware

of each other. They collided at full speed, laying each other out. That

was the signal for the crowd to get completely out of hand. While Bell

and Temple were receiving attention, missiles rained down on the players

and the trainers attending them. Les Cocker and referee Ken Stokes were

struck by flying coins. Desperate to quell a potential riot, Stokes promptly decided on drastic

action - he ordered both sets of players to the dressing rooms to give

them and the crazed crowd time to cool off. It was some minutes before Bell came round sufficiently for Les Cocker

and his team mates to carry him off, while Temple required a stretcher. The referee laid down the law to the players during the halt in proceedings.

Jim Storrie: 'He came into each team's

dressing room and said that if we didn't stop kicking each other and start

playing football, he would report us to the FA.' The game resumed after a ten-minute gap 'on a pitch festooned with the

cushions and rubbish thrown by the crowd … amid a storm of jeers and catcalls'.

Both Bell and Temple were back in action, seemingly none the worse for

wear. The break did little to soothe the fury of fans or players. After the resumption, some of the tackling, particularly by Norman Hunter

and Roy Vernon, was brutal in the extreme and the match continued to seethe

with an undercurrent of barely concealed aggression. Hunter was booked,

and the referee lectured Bremner, Collins, Vernon and Stevens for dangerous

play. A number of players were fortunate to avoid joining Brown in the

dressing room. Bobby Collins became more dominant, seemingly relishing the kind of hostile

environment in which he thrived. Ian W Guild: 'Collins stood out on his

own as the complete footballer. His generalship and shrewd distribution,

together with his willingness to work at both ends of the field, guaranteed

Leeds the lion's share of the ball.' He ensured that United made the most

of their man advantage, exhorting his troops to stretch the game and force

Everton to work hard for any possession. Jack Charlton proved what a resolute and accomplished stopper he had

become and received steadfast support from Bremner, Hunter, Bell and Reaney.

United manfully resisted the Merseysiders' closing assault as they went

all out for an equaliser. Everton were kept at arm's length as United

squeezed out a 1-0 result. The Yorkshiremen had to contend not only with

some breakneck football from the home side in the closing minutes, but

also with fierce antagonism from the 40,000 Scousers in the crowd. Collins said later: 'It was diabolical … they blamed us, yet some Everton

players were going over the ball time and time again. But the referee

is in control of the game … it is up to him. When Sandy Brown got sent

off, it was like a fuse on a bomb being lit … it really got a bit nasty

and brutal. There were a lot of hard challenges that day. But you can't

turn the other cheek or they'll kick you.' Bagchi and Rogerson: 'After the game an angry, booing crowd had to be

dispersed by mounted police from the streets surrounding the stadium.

From the safety of their coach, which had to withstand another barrage

of missiles, the Leeds players must have reflected on the ill feeling

that had almost overwhelmed them. How far had they been responsible for

provoking it? … When faced by teams willing to stand toe to toe with them,

Leeds always tended to incite the wrath of opposition supporters because

to them the game would appear one long succession of Leeds' fouls. In

fact, the foul tally in the Everton match shows Leeds committing twelve

to Everton's nineteen - but it was the manner in which Leeds carried themselves.

United never seemed to care about their reputation, they never retreated

when the opposition attempted to turn the tables and they knew just how

far to wind up the opposition without winding up the referee. It didn't

matter if the match statistics exonerated them; they were such perfect

villains.' The frightening scenes provoked some predictably hysterical press coverage. The Times: 'For the first time in the history of the Football

League both sides in a match on Saturday were ordered off the field for

a space of five minutes to allow the tempers of both the crowd and the

players to cool … Such an event has occurred frequently enough abroad

... It happened even here a year ago when the referee abandoned an international

at Hampden Park as the Austrians got out of control against Scotland.

It happened, too, lower down the supposed social football scale in 1959

when the teams of both Dartford and Gravesend were given communal marching

orders. Those were isolated incidents within these isles, roundly condemned

at the time. But for supposedly civilised senior British players now to

follow suit against each other is something new and menacing. The image

of the game, already damaged in other ways, cannot stand much more of

this. 'The front line of battle now was Merseyside. Goodison Park has already

gained an unsavoury tribal reputation for vandalism. Leeds United, too,

more recently have earned black marks for ill temper on the field. The

marriage of these two dangerous elements sparked off the explosion. But

the whole business goes much deeper. At a time of national remembrance

one remembered the old days when play certainly was equally rough, if

not physically rougher. Yet now the modern sophisticates can be more sinister,

more subtle in their methods. The high rewards at stake, the financial

incentives, have brought new, more savage pressures. 'For all those who love the game this brings a deep sense of pain. But

it is no use burying sensitivity in the sands. Stern, practical steps

must be taken now to cure the malaise of a minority that can spread dangerously.

Grounds should be closed; players should be soundly punished where it

hurts most - in their pockets.' Don Revie fell back on his favourite ruse of pointing the finger at others:

'After the incidents of this weekend I must defend my club and my players

after all the bad things that had been said about them. I feel it started

last season when we were in the Second Division when we were tagged as

a hard, dirty side by the press. 'I am disgusted by these attacks on us and I ask that we be judged fairly

and squarely on each match and not on this unfair tag that we have got

… we The incidents at the game raised the hackles of football's establishment

- the patriarchal, cigar-smoking president of the Football League, Barnsley's

Joe Richards, hinted at firm action to follow: 'I think the time has come

to investigate the whole question of these ugly scenes and rows. They

are bringing a bad image to football ... Something must be done and we

must find out the causes. We shall certainly look at it from the bonus

point of view and find out whether that is causing the trouble. Competition

is healthy and we must have promotion and relegation, but things seem

to be getting too keen. It may be that players are getting too much money

for points. It is all very disappointing, because players are getting

good wages compared with people in industry, but this trouble is happening

too regularly.' Richards was the man forced to back down by PFA chairman Jimmy Hill over

football's maximum wage in January 1961. Previously, a maximum of £20

a week in season and £17 in the summer had been the rule - Hill

brought a long and protracted dispute to a head by threatening a players'

strike, forcing the Football League and the clubs to relent. Richards served as League President from 1957 until 1966. League

secretary Alan Hardaker wrote of him: 'Joe Richards was a small, dapper

man, a tough old bird who learnt the business of life in the Yorkshire

coalfields. His only language was honest Yorkshire but he seemed able

to make himself understood no matter what country he was in. The impression

he left was always lasting and favourable.' Richards, however, had been clearly scarred by the memory of the players'

revolt and was convinced that the growing preoccupation with money was

at the root of all football's ills. He had earlier used his own resources

to pay for the Football League Cup trophy to be manufactured when Hardaker

came up with the idea for the new competition in 1960. In the end, despite all of Richards' vehemence and ire, the only punishment

meted out by the FA was against Everton. Sandy Brown was suspended for

two weeks and Everton were fined £250 for the behaviour of their supporters.

United chairman Harry Reynolds noted chirpily, 'I can make no comment,

for the decisions do not concern us.' The events of November 7 cemented the reputation of Revie's United in

the minds of many for years to come - they were a bunch of thuggish yobs

who would stop at nothing to win a football match. While there was certainly

some truth in that conclusion, Everton were the greater offenders on the

day, and the FA's criticism three months before did much to create an

atmosphere of tension and a readiness to 'get your retaliation in first'. Leeds came out of the game vilified and unloved, pilloried for their

readiness to remove the gloves. They had ruffled the feathers of the football

hierarchy and were in vigorous pursuit of an improbable League title.

For a team who had never come within a country mile of any major honours,

the success of the Leeds juggernaut in securing points was much more important

than being loved … Don Revie would look back in later years and wince

at the approach, but at the time his judgement was swayed by the astonishing

success of his men's physical and mental aggression. There is no way of pinning down exactly when the infamous myth of

'Dirty Leeds' began: it could have been the day in early 1962 when Glasgow

street fighter Bobby Collins answered

the call of Don Revie, thereby importing

an aggressive streak the size of the M1 into Elland Road; it might have

been over Christmas 1963, when United clashed twice with promotion rivals

Sunderland and players on both sides indulged in onfield thuggery of the

worst kind; or perhaps the month before, when United entertained third

placed Preston North End and the aggression was so intense that the referee

halted the game after an hour to give the players a final chance to calm

down and get themselves under control.

There is no way of pinning down exactly when the infamous myth of

'Dirty Leeds' began: it could have been the day in early 1962 when Glasgow

street fighter Bobby Collins answered

the call of Don Revie, thereby importing

an aggressive streak the size of the M1 into Elland Road; it might have

been over Christmas 1963, when United clashed twice with promotion rivals

Sunderland and players on both sides indulged in onfield thuggery of the

worst kind; or perhaps the month before, when United entertained third

placed Preston North End and the aggression was so intense that the referee

halted the game after an hour to give the players a final chance to calm

down and get themselves under control. would also maintain that the Dirty Team tag, which was blown up by the

Press, could prejudice not only the general public but the officials controlling

the game, and to put it mildly, could have an effect on the subconscious

approach of both referee and linesmen, to say nothing of the minds of

spectators, especially some types who are watching football today. It

could lead to some very unsavoury incidents.'

would also maintain that the Dirty Team tag, which was blown up by the

Press, could prejudice not only the general public but the officials controlling

the game, and to put it mildly, could have an effect on the subconscious

approach of both referee and linesmen, to say nothing of the minds of

spectators, especially some types who are watching football today. It

could lead to some very unsavoury incidents.' by Billy Bremner. Seconds later Jack Charlton suffered a similar fate

at the hands (or feet, rather) of an opponent. That was that - the battle

lines were drawn: this was going to be a tasty affair.

by Billy Bremner. Seconds later Jack Charlton suffered a similar fate

at the hands (or feet, rather) of an opponent. That was that - the battle

lines were drawn: this was going to be a tasty affair. For

a time, nobody knew whether the game had been suspended or abandoned.

Shortly, the loudspeakers announced that play would restart in five minutes,

although Stokes warned that the match would be called off if more missiles

were thrown.

For

a time, nobody knew whether the game had been suspended or abandoned.

Shortly, the loudspeakers announced that play would restart in five minutes,

although Stokes warned that the match would be called off if more missiles

were thrown. were

wrongly labelled by the press and then by the Football Association. The

result has been that opposing teams have gone on to the field keyed up,

expecting a hard match. I think the number of opposing players sent off

in our matches proves it.'

were

wrongly labelled by the press and then by the Football Association. The

result has been that opposing teams have gone on to the field keyed up,

expecting a hard match. I think the number of opposing players sent off

in our matches proves it.'