Part

1 An appreciation - Part 2 Home grown hero

- Part 4 Back from the dead - Part

5 End of the line

Part

1 An appreciation - Part 2 Home grown hero

- Part 4 Back from the dead - Part

5 End of the line

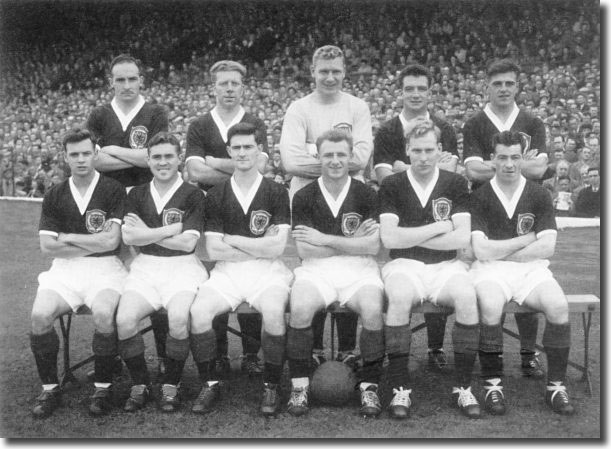

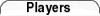

Bobby Collins and the Scottish international team set off for the 1958

World Cup finals in fine heart - Collins' brace brought a 2-1 victory

in their final warm-up match in Poland on 1 June and took his record to

6 goals in his previous eight internationals. The Scots had lost only

once in that run. Bobby was a key member of the team, having played in

all but five of 21 games since his recall in May 1955.

The Scottish FA approached the tournament in Sweden much more professionally

than on previous occasions. The Scots had qualified for the 1950 finals

in Brazil as runners-up in the Home International Championships to England,

but declined to go because they had not finished top. Their participation

in 1954 was a disaster: the squad had been restricted by the SFA to a

team and two reserves. They lost both games (one by 7-0) and manager Andy

Beattie resigned between matches, citing interference from selectors as

the reason.

In 1958 a full 22-man squad travelled to Sweden. The players were rewarded

with £3,250 for their efforts in qualifying, and on the promise of £50

an appearance and £30 as a reserve in the tournament itself. There were

further bonuses on offer for making progress to the latter stages of the

tournament.

Bobby had two Celtic colleagues, Bobby Evans and Willie Fernie, alongside

him in the squad, which also included Tommy Younger, Eric Caldow, Tommy

Docherty, Dave Mackay, John Hewie, Graham Leggat, Stewart Imlach and Jackie

Mudie.

The Scots faced a tough qualifying section, involving Yugoslavia, Paraguay

and France. They kicked off with a match against the Slavs on 8 June but

were cheated out of a triumph by some cynical tactics and inept refereeing,

finishing with a 1-1 draw.

Gair Henderson in the Evening Times: '[Yugoslavia] were adept

at every aspect of obstruction and destruction. They pushed their bodies

between the Scots and the ball at every opportunity, and they were given

a free hand by a referee whose tolerance of these tactics and his intolerance

of the Scottish tackling had to be seen to be believed.'

Hugh Taylor in the Evening Citizen: 'Wee Bobby Collins, playing

his greatest international, came to our rescue. Collins was inspired.

He took command of the game. How the hard men from Titoland knew that.

They tried to crash him out of the game. First right-back Sitjakovic got

him when his back was turned and sent him reeling to the ground. Bobby

got up, shook his head and shook it again when he saw referee Wyssling

wave play on instead of ordering off the Slav. Next Bobby suddenly stopped

short and put his hand to his mouth after Sekularac had elbowed him in

the face. How I admired Collins, criticised so often for his impetuosity,

for his restraint in this match. He paused only to put in more firmly

two loosened teeth, and played even more brilliantly.'

The

draw saw the odds on Scottish qualification shortening sharply. They now

faced Paraguay, who had crashed 7-3 to France in their first group game.

Unfortunately, there was another hard luck story, with a 3-2 reverse being

blamed on one-eyed refereeing and opposition tactics. Collins' goal after

76 minutes only made for a tight finish.

The

draw saw the odds on Scottish qualification shortening sharply. They now

faced Paraguay, who had crashed 7-3 to France in their first group game.

Unfortunately, there was another hard luck story, with a 3-2 reverse being

blamed on one-eyed refereeing and opposition tactics. Collins' goal after

76 minutes only made for a tight finish.

To have any chance of going through, the Scots needed to beat France

in their final match. This was highly unlikely, as the French boasted

the scoring talents of Juste Fontaine, already leading the way with five

goals from two games. Scotland went down 2-1 after missing a penalty,

and were outplayed throughout.

It was a depressing end to a trip that had promised much, and the players

had little to show for the occasion but commemorative jerseys. At the

time, the Scottish FA only awarded caps for games against the other home

nations. Stewart Imlach's son, Gary, later launched a campaign to have

the decision retrospectively changed. Finally, in 2006, the SFA bowed

to pressure and awarded commemorative caps to more than 80 former internationals,

who had never received actual caps. Among the 80 were 1958 squad members

Imlach and Eddie Turnbull.

Collins remembers the tournament as follows: 'We could be proud of our

efforts. Okay, we failed to reach the quarter finals, but that was due

to the opening game when we were extremely unlucky. The refereeing was

questionable to say the least, as it was against Paraguay when we lost.

The French were a class act and possessed the top striker of the tournament

in their side. Not every footballer gets the opportunity to play in the

World Cup. I had and I managed to grab a goal.'

back to top

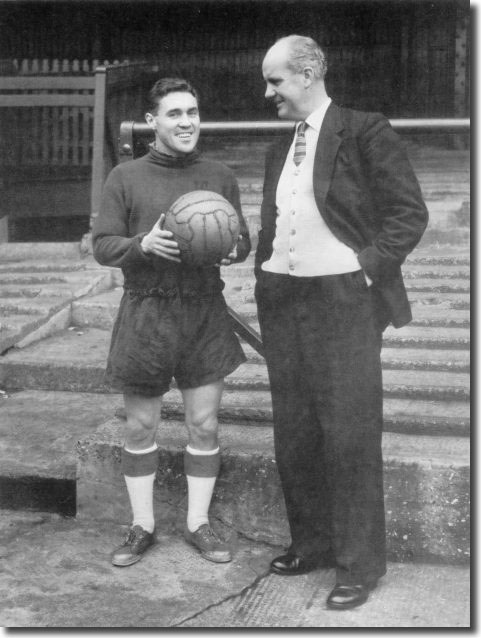

Playing on the international stage had given Bobby Collins itchy feet,

and he requested a transfer from Celtic in August 1958, intent on proving

himself in the English game. He later recalled: 'Behind the scenes things

weren't ideal. Jock Stein, Billy McPhail and Sean Fallon had retired and

Willie Fernie and Charlie Tully would soon depart. The Parkhead team I

was an integral part of was breaking up; we'd had our swan song in the

League Cup final and I felt that I needed to find a new challenge. I'd

been fortunate to play for such a great club because not everyone gets

such an opportunity.

'It was sad because I'd been there nigh on ten years … In my entire time

at the club [manager Jimmy McGrory] only gave one team talk and that was,

"Boys, the turnstiles aren't clicking." That was it. Incredible.

He wanted to get rid of me. I was playing golf at Tower Glen and when

I came off, the secretary said there'd been a call from Mr McGrory and

I was to phone him back. So I did and he said, "Everton are interested

in you, will you go?" It wasn't "Do you want to go?" and

I was never one to stay anywhere if I was not wanted.'

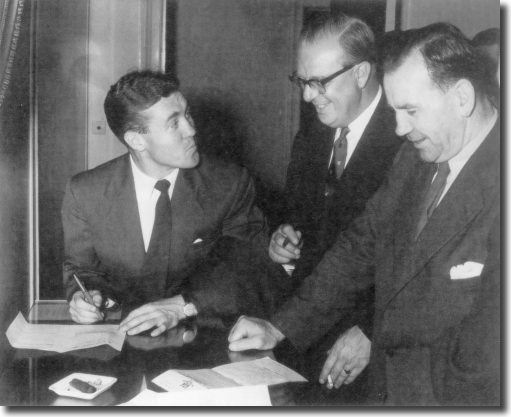

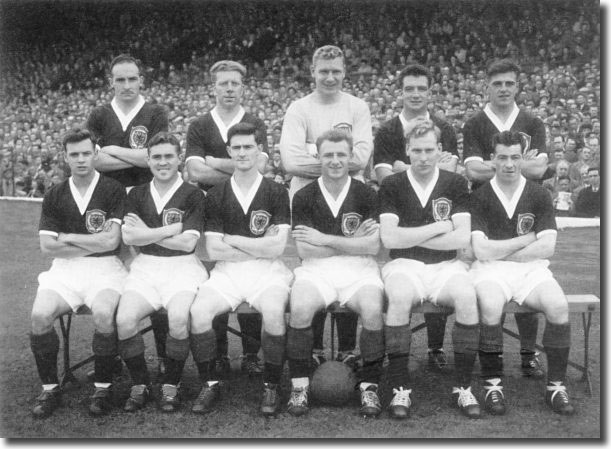

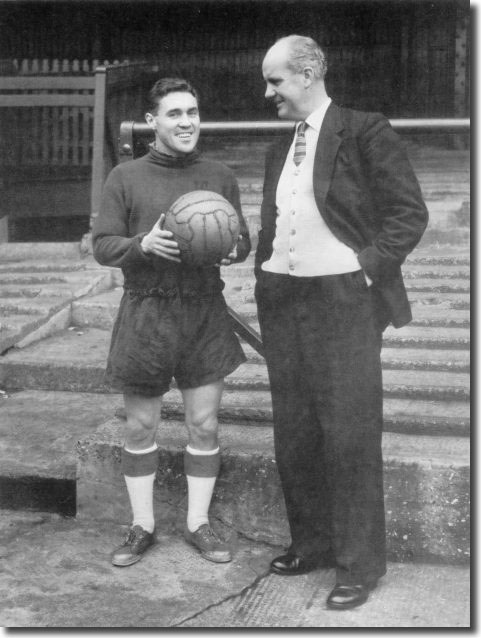

Everton were the first club who made a move and Collins was on his way

to Goodison in a £23,500 deal on 12 September 1958. Everton's manager

at the time was Ian Buchan, but he was sacked shortly  afterwards for poor

results and replaced by former Irish international Johnny Carey. Collins

spoke later of the two men: 'Ian Buchan knew the game but he was too much

of a theorist, having never played the game at the top level. Johnny on

the other hand had a wealth of experience and understood players more

as he had been successful in his own playing career. A great tactician,

he gave you a job and it was down to the player to make it work.'

afterwards for poor

results and replaced by former Irish international Johnny Carey. Collins

spoke later of the two men: 'Ian Buchan knew the game but he was too much

of a theorist, having never played the game at the top level. Johnny on

the other hand had a wealth of experience and understood players more

as he had been successful in his own playing career. A great tactician,

he gave you a job and it was down to the player to make it work.'

As with Celtic when Collins arrived at Parkhead, the Merseysiders were

at a low ebb, having finished 16th, just five points clear of relegation.

They had been without a trophy of any sort since securing the League title

in the last season before World War II.

James Corbett from Everton - The School of Science: 'In the opening

fixture of the 1958/59 campaign … Everton were crushed at Filbert Street.

"Two goals to nil Everton lost at Leicester," reported the Football

Echo. 'But the margin may well have been heavier and that is making

allowance for the desperation of a hard-worked defence." Four days

later they lost 1-4 at Goodison to Preston North End. The next Saturday,

30 August 1958, Newcastle inflicted a 0-2 home defeat, which was greeted

with slow handclapping and angry shouts.

'Soon letters were flooding into the local newspapers. "It is perfectly

obvious that there is something wrong at Goodison. Despite the accent

on youth they have produced nothing worth bragging about. When Mr Buchan

came to Goodison he was quoted as saying that Everton were playing a negative

type of football, I don't know what he calls the type they're dishing

up now. If it were any more negative it would be non-existent," wrote

T Hartley of Little Crosby.

'Preston inflicted a fourth straight defeat (1-3) in the return at Deepdale

before Arsenal visited Goodison on 6 September. Hopes that the miserable

start would come to an end were quickly confounded. Everton were thrashed

1-6. "This was a massacre at Goodison," wrote Michael Charters,

in the Football Echo. "Everton were completely outplayed at

every point by a brilliant Arsenal team who gave them a footballing lesson,

plus goals." Only Temple's consolation five minutes from the end

prevented the record 0-6 Goodison defeats of 1912 and 1922 being equalled.

'The following Monday the board met to decide Buchan's fate. Earlier

claims that Everton had been the fittest team in the division were dismissed

by the chairman, Dick Searle, who stoked controversy when he said: "Everton

are three yards slower than opponents they have met this season."

Yet for three days - which saw Everton's sixth straight defeat (1-3) at

Burnley - there was silence. Then, in quick succession, they announced

three surprises.

'First, Harry Wright, Buchan's first-team trainer, was sacked, and Gordon

Watson stepped up to take over.

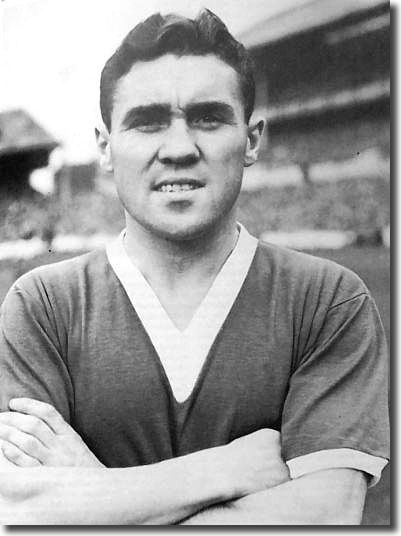

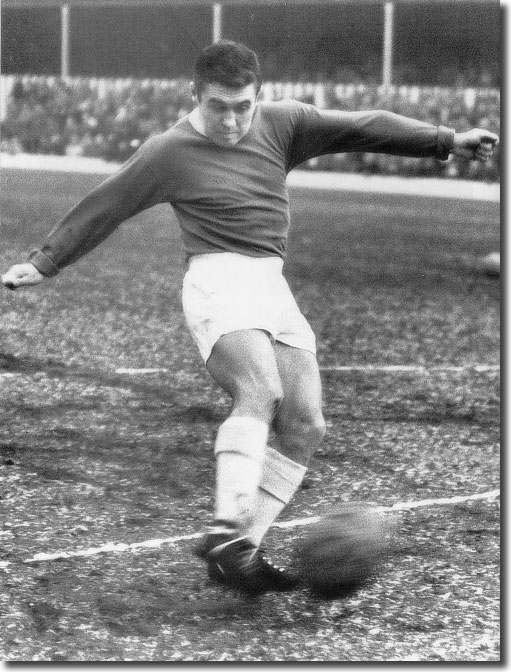

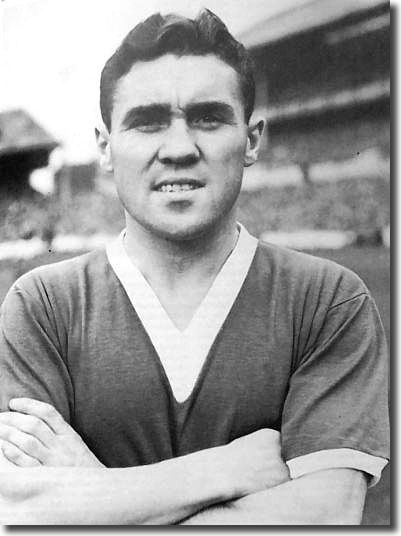

'Then Celtic's Bobby Collins was signed for £24,000. He was five foot

four inches of tenacious skill, biting aggression and impish brilliance,

and his arrival made front page news on Merseyside. Despite the abysmal

start to the season, the Liverpool Echo's Leslie Edwards was optimistic

that the new signing could help Everton rise from the depths of the First

Division: "Everton will find that the £24,000 they have spent will

be repaid fully by a player Scotland will be sorry to lose." Twenty-four

hours later, Collins had inspired Everton to their first win of the season:

a 3-1 victory over Manchester City, and Edwards was singing the new boy's

praises in the Football Echo. "First appearances suggest that

Collins will be well worth every penny of his transfer fee and although

one man may not be the complete answer to Everton's troubles, he can go

a great part of the way to restoring Everton's glamour." Two minutes

before the end of the game Collins had produced a '"-book finale",

with a shot so powerful it slipped through the goalkeeper's grasp and

into the net to make the score 3-1 in Everton's advantage.

'His influence at Goodison rallied his team-mates and they began to pick

up valuable points. A ferocious tackler, Collins earned the nicknames

the "Little General" and "Pocket Napoleon" and was

more than capable of rattling the bones of any giant who got in his way.

Not only were his goals and tackling vital to the team, but he was at

the creative heart of an inconsistent Everton side. He could pass with

deadly accuracy to colleagues in dangerous positions and such was his

influence that, more than 35 years after his departure, Brian Labone still

had cause to present him to a half-time Goodison crowd as "the man

who single-handedly saved Everton from relegation - twice".

'Days after the Manchester City win, it was revealed that Blackburn Rovers'

manager, Johnny Carey, was to be appointed Everton boss. Carey, a soft-spoken

Dubliner, had captained Manchester United's post-war side, helping them

to league runners-up in three consecutive seasons and also to the FA Cup

Final, which they won in 1948. His first taste of management was at Ewood

Park where he led Blackburn to the top flight in the 1957/58 season, and

he was seen by the Everton directors as the ideal successor to Ian Buchan.

Carey immediately put his free-flowing football principles into practice

at Goodison, his motto being "Only the keeper stops the ball."

'However, it was four weeks before he could take up the managerial reins:

he had agreed - always a man of honour - to serve out a four-week notice

period at Ewood Park. Before that time could elapse, Everton had suffered

their record defeat on 11 October 1958 to Tottenham Hotspur: 1-6 down

at half-time, they went on to lose 4-10, even though Jimmy Harris scored

a hat-trick. The last time 14 goals had been scored in a top-flight match

was in 1892 when Aston Villa beat Accrington Stanley 12-2. "Comment

is superfluous," wrote the Football Echo.

'Following his October arrival, Carey steadied the ship, leading Everton

from the relegation spots to the relative respectability of sixteenth.

Although Everton had scored 71 goals, their defence let them down, conceding

87. It was the pattern of things to come.'

Collins had a stirring debut season for the Blues and retained his international place, scoring 3 times in six

appearances, though defeat in Portugal in June 1959 seemingly marked the

end of his Scotland career, as he lost his place thereafter.

the Blues and retained his international place, scoring 3 times in six

appearances, though defeat in Portugal in June 1959 seemingly marked the

end of his Scotland career, as he lost his place thereafter.

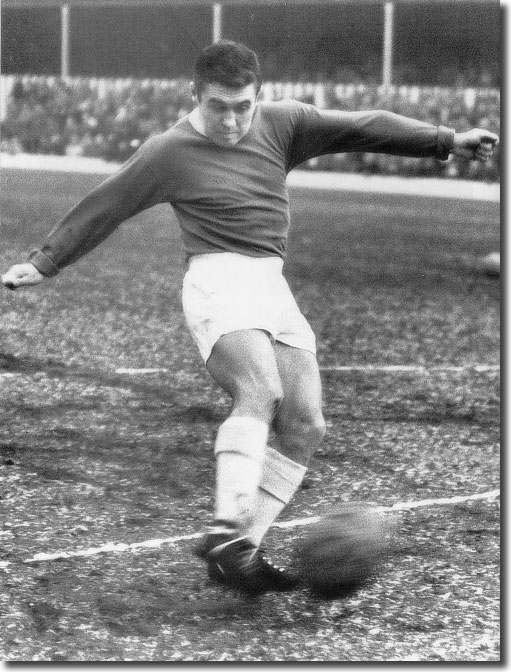

At Goodison, the Scot went from strength to strength, assuming the club

captaincy after fans' favourite, centre-forward Dave Hickson, crossed

the city to join Liverpool. It took Everton seven games to record their

first win in 1959-60, with Collins' third goal of the season coming in

a 6-1 win against Leicester. From then on, it was a roller coaster season,

punctuated by heavy defeats and easy victories, though for the most part

the Merseysiders struggled. They finished fifteenth, only three points

from relegation in a tight finish that saw just 6 points covering the

clubs between 11th placed Blackpool and Leeds United, relegated in 21st

spot

back to top

Collins stood out as the shining star in a dismal season, as noted by

Derek Wallis in the Daily Mirror: 'Bobby Collins has made nonsense

of all transfer fees. You couldn't buy Johnny Haynes for that, Jimmy McIlroy

or Albert Quixall. I cannot remember a greater display of all the inside-forward's

subtle skills since the war than the torture of Chelsea by Collins.'

The schemer, now 29, had successfully adapted to the English League and

was among the best players around, even though his team were struggling.

The club's fortunes were soon to improve as Everton began to thrive thanks

to the financial backing of John Moores, founder of the Littlewoods organisation,

who was elected chairman in the summer of 1960. The club could now afford

to buy the best, and secured such talents as Roy Vernon, Jimmy Gabriel,

Billy Bingham, Tommy Ring and Alex Young. The new players brought refreshed

optimism.

James Corbett: 'By Christmas 1960, Everton were third and being talked

of as genuine title challengers. It was a stark contrast to any season

in the 13 that had passed since the war, but Carey's side were entertainers,

not winners. They were the sort of side who could thrill with a 3-1 win

at Burnley on Boxing Day 1960, then lose miserably (0-3) to the side in

the return fixture at Goodison just 24 hours later. Indeed that same defeat

marked the onset of a run of 10 losses in 13 games. It was not catastrophic

and Everton fell only as far as sixth, hut it was enough to convince Moores

that Carey would never be a winner He recognised that Carey's team often

lacked discipline or the killer touch.

'When the end of March came, speculation was rife about Carey's future.

It intensified when Harry Catterick, now manager of Sheffield Wednesday

but rumoured to be of interest to the Everton board, resigned unexpectedly.

Wednesday were in second place.

'Then, on Friday 14 April 1961, Carey and Moores travelled to London

for an FA meeting. Even though Everton had beaten Newcastle United 4-0

at St James's Park the previous Saturday, speculation was more intense

than ever about Carey's future. Wanting clarification, he demanded a meeting

with his chairman. Moores suggested that they reconvene and the two men

took a taxi to the Grosvenor House Hotel. During that journey, Carey repeated

his request for clarification on his future. Moores, always a man of principle,

went straight to the point. He told Carey that he was being replaced.'

Harry Catterick was introduced as manager two days after Carey's removal.

Collins was sad to see the Irishman go, but hinted at the reasons: 'Johnny

insisted that we enjoyed our football. The only flaw he had was that he

wasn't hard enough with the players and some did take liberties. Discipline

was not tight enough and this stopped him from becoming a great manager.

Top managers need a ruthless streak, as players do, if they want to make

it at the highest level.'

Collins missed just two games as Everton ended the season fifth, and

finished second top scorer to Roy Vernon in the league with 18 goals.

He was popularly acknowledged as the catalyst for the club's improving

fortunes, as noted in a local paper:

'He is the greatest thing that has happened at Goodison Park since Dixie

Dean. This dynamo of a man, better than a dynamo because he never runs

down, arrived here in the Ian Buchan era when Everton's position was pretty

desperate and some general was urgently needed to take command of their

attack.

'Everton's climb began from the day he arrived … initially, Collins found

he was wanted as much in defence as he was in attack. Now, with the side

more balanced, he can concentrate on his real mission, getting the side

on the offensive and keeping them there.

'Wee Bobby lacks nothing in courage either. He'll tackle the biggest

and strongest and will come out, more often than not, with the ball at

his feet. Collins makes goals or takes them with equal facility. He, more

than anyone, has helped his club to win back thousands of lost spectators

by ensuring that they will get 90 minutes  of

effort and football entertainment.'

of

effort and football entertainment.'

Johnny Carey had said that his aim was 'to give Everton entertaining

and, if possible, winning football'. It was clear that Catterick's approach

was absolutely the other way round, and he would stand no nonsense from

the players. Roy Vernon was sent home from an end of season tour to America

for breaking a curfew.

The Toffees kicked off the 1961/62 season with an impressive 2-0 win

against Villa with goals from Young and Bingham, but then lost by the

same score at West Bromwich. Collins sustained a knee ligament injury

that kept him out of the next eight games, only three of which were won.

He returned for a match at Goodison against Arsenal, which Everton won

4-1, the first of an impressive run of performances. Alex Young was the

inspiration.

James Corbett: 'Young was quickly emerging as a favourite at Goodison,

wowing the crowd with his delicate flashes of genius. His "effect

on the team was enormous", Labone claimed later, "particularly

on the defence. We felt that here was a man you could give the ball to

in any situation. He could give us a breather by keeping the ball up there,

occupying all the attention of the opposition, giving us time to regroup."

Impressive though he undoubtedly was, Young still had to stake his claim

for immortality. It wasn't long in coming.

'At the end of the first week of October 1961 tenth-placed Everton played

Nottingham Forest, who held fourth position. Though Everton had won the

same fixture 6-1 less than two years earlier, few Evertonians could have

anticipated a repeat of that hiding, or the way in which Young dominated

events from start to finish. Jimmy Gabriel scored first, running on to

Young's sideward header and steering the ball past Grummitt for his second

goal in successive matches. Vernon added a second on 33 minutes. Young

raced down the wing and into the Forest penalty area. His perfectly calculated

pass was controlled by the unmarked Welshman, who lashed the ball home.

Then, Young's well-directed header from Fell's cross made it 3-0 a minute

after half-time, and he returned the compliment 10 minutes later, playing

in Fell for the first goal of his Everton career.

'Young was now on fire and the Forest defence were finding it impossible

to check the Scot's brilliance. He was inspiring Everton to exhibition-like

football and started the move for Everton's fifth goal. Picking up the

ball by the half way line he swerved past a Forest defender and dribbled

down the right before flicking the ball to Bingham. His cross was accepted

by Collins on the penalty spot and he controlled the ball, then imperiously

back-heeled it into the path of Fell, who tapped home his second from

four yards. Then, on 76 minutes, Young lobbed the ball in for Bingham

at the far post, headed across the goal and Vernon side-footed home his

second and Everton's sixth.

'It was, noted one observer, "The finest exhibition of centre-forward

play since the days of Dixie Dean and Tommy Lawton - that is how I rate

the performance of Alex Young ... His trademark was on all six goals and

it was not his fault there were not three or four others." The Liverpool

Echo's Leslie Edwards said of Young: '"t is not necessary for

a player with his extraordinary gifts to play a blood and guts centre-forward

game. With a slight feint of the shoulders he gets them going the wrong

way. Then he drifts past them almost lazily. Like Matthews and other men

of football genius he always seems to have time to think and space in

which to move. He won't get a packet of goals, but he'll make hundreds

of others."'

back to top

Bobby Collins picked up another injury that meant he missed the excellent

3-0 win over Double winners Spurs at the beginning of November, but returned

in time to help the Blues beat Manchester United 5-1. He started the rout

with his first goal of the season, from an 18-yard drive.

Unfortunately, Harry Catterick seemed to have set his mind against the

schemer and was critical of his form. Collins scored twice against Fulham

on 23 December, yet was roundly berated, as he recalled: 'After scoring

two against Fulham, Catterick  told me I was not the player I used to be.

I was not happy and told him so. I'd been the best Everton player that

day and I'd got a rollicking. I knew that my days were numbered.'

told me I was not the player I used to be.

I was not happy and told him so. I'd been the best Everton player that

day and I'd got a rollicking. I knew that my days were numbered.'

The Scot was later upbraided by chairman John Moores during a clear the

air meeting: 'As captain I was first to receive his opinions and I was

not happy when Mr Moores inferred that I wasn't giving my all. Nobody

criticises my work rate, winning was everything to me. I was fuming and

let him know. After the meeting without thinking I told a journalist the

whole story. The next day I had a frank discussion with Mr Moores and

told him if he didn't think I was giving everything he could get rid of

me. I soon realised how much the club meant to him. His critical words

were aimed to get the team fired up again and we parted on good terms.

By the weekend, however, my chat with the journalist was headline news.

I apologised to the chairman because details of the team meeting should

have stayed within the club, and credit to him, he realised that my actions

were in the heat of the moment and that was the end of the matter.'

The chairman might have held no grudge, but Harry Catterick had decided

that it was time to move Bobby Collins on. Catterick had not yet dabbled

in the transfer market, but was now ready to do so. Athletic Blackpool

keeper Gordon West arrived and made his debut in a 4-0 thrashing of Wolves

on 3 March. The game marked Collins' finale in Everton colours. Denis

Stevens had been signed from Bolton and was earmarked for Collins' inside-right

slot. It was suggested that Bobby should fight it out for a place on the

right wing with Billy Bingham. He rejected the idea and decided to pursue

his career elsewhere.

Everton were flying high at the time and on the way to a fourth place

finish, their highest since 1939, but Collins' mind was made up: 'I had

an idea my days were numbered. I still knew I could play. I just thought,

fine, there's something wrong here. If they don't want me, I'll leave.'

Brian Labone was Everton centre-half at the time and recalls: 'Bobby

Collins made the biggest impact on me during my career. When I broke into

the side on a regular basis in 1959, Bobby was skipper and the key player

in the first team. Football coverage in the media during the 1950s was

very different to now. Of course, I'd heard of Bobby because he was a

Scottish international and had played for Celtic, but it wasn't until

I saw him in training that I realised just how good he was.

'Bobby was the ultimate professional … He taught me a lot during the

early stages of my career. I remember challenging him for a ball during

a training match. I was over six foot, so you'd think it would be a mismatch

going in against Bobby, but he went in hard and took me out. I was amazed

by his strength, aggression and desire. Next time I went in a lot firmer

and he said with a wry smile, "you're learning, son," but that

was Bobby, no quarter was given on or off the pitch. I learned a lot from

him.

'When I got into the first team we were in a bad position. During a difficult

couple of seasons he kept us up and transformed Everton. Most sides had

a Scot who brought a touch of iron to the side. Tottenham had Dave Mackay,

we had Bobby and he got us out of trouble time and again. He also weighed

in with crucial goals.

'Harry Catterick had a policy of selling players before their sell by

date. He usually got it right, but he got it wrong with Bobby Collins.'

A number of clubs expressed an interest in the Scot when news of his

availability broke, but it was Leeds United, struggling at the foot of

the Second Division, and their young manager Don

Revie, Collins' senior by just four years, who were the keenest. United

trainer Les Cocker watched Collins in the FA Cup defeat at Burnley on

17 February and recommended a move, which went through on 8 March.

Don Revie: 'A journalist tipped me off that Everton might be willing

to let Bobby go, so after we got confirmation of this from their manager,

Harry Catterick, I travelled to  Goodison the following morning, with two

of our directors, to open negotiations. I spent an hour with Bobby after

training and he told me in no uncertain terms that he felt that he still

had a lot to offer as a First Division player, didn't fancy going to a

club with one foot in the Third. We left it that he would think it over

for a couple of days and get back to me. But as we headed home, I decided

to have another chat with him. I remember, we arrived at his house at

2 pm and waited in the car no less than five hours before he turned up.

We didn't leave until 2.30 am the next morning, but by that time, Bobby

had agreed to join us.'

Goodison the following morning, with two

of our directors, to open negotiations. I spent an hour with Bobby after

training and he told me in no uncertain terms that he felt that he still

had a lot to offer as a First Division player, didn't fancy going to a

club with one foot in the Third. We left it that he would think it over

for a couple of days and get back to me. But as we headed home, I decided

to have another chat with him. I remember, we arrived at his house at

2 pm and waited in the car no less than five hours before he turned up.

We didn't leave until 2.30 am the next morning, but by that time, Bobby

had agreed to join us.'

Collins: 'Don Revie was a lovely fella and was a good talker. He outlined

his plans and he offered me the same money as I was on at Everton. Considering

Leeds were in the Second Division, I thought that was something. It showed

a bit of faith. I knew they had some good players, too. What I didn't

know was they were second bottom of the Second Division at

the time. It was like that when I went to Everton too. I knew they

were a big club, but I had no idea they'd played six games and lost six.

'I'd been to see Don and was happy with things, but when I got home my

brother-in-law told me some fella had been on the phone a few times asking

for me. He said he was Scottish, but he wouldn't leave a name. I thought,

fine, and left it at that. I didn't think any more of it. The next day

the phone went again and this voice growled, "Son, is it true, ye've

signed for Leeds?" I could only say, "Yes, Mr Shankly,"

and to his credit, he said, "Ah well, orra best anyway, son."

Who knows what might have happened if he'd rung a day earlier.'

A £24,000 fee was agreed and Bobby Collins became a Leeds United player

in one of the best bits of business that Don Revie ever did. Nevertheless,

it was a record for both clubs at the time.

In the days following the move, Collins had some second thoughts, as

he recalls: 'I was so keen to get away from Everton that I accepted Leeds'

offer without really weighing up all the pros and cons. Don allowed me

to stay on living in Aintree and just to go to Leeds a few days a week

for training, but I didn't think this was practicable, not for me nor

the club. At the same time, I didn't want to uproot my family from Aintree,

and so it seemed the only solution to the problem would be a move to a

club nearer Liverpool. I had a long chat with Don, and he persuaded me

to give the whole business a longer trial. We did move to Leeds - and

I never looked back.'

Part 1 An appreciation - Part

2 Home grown hero - Part 4 Back from the dead

- Part 5 End of the line

back to top

Part

1 An appreciation - Part 2 Home grown hero

- Part 4 Back from the dead - Part

5 End of the line

Part

1 An appreciation - Part 2 Home grown hero

- Part 4 Back from the dead - Part

5 End of the line  The

draw saw the odds on Scottish qualification shortening sharply. They now

faced Paraguay, who had crashed 7-3 to France in their first group game.

Unfortunately, there was another hard luck story, with a 3-2 reverse being

blamed on one-eyed refereeing and opposition tactics. Collins' goal after

76 minutes only made for a tight finish.

The

draw saw the odds on Scottish qualification shortening sharply. They now

faced Paraguay, who had crashed 7-3 to France in their first group game.

Unfortunately, there was another hard luck story, with a 3-2 reverse being

blamed on one-eyed refereeing and opposition tactics. Collins' goal after

76 minutes only made for a tight finish. afterwards for poor

results and replaced by former Irish international Johnny Carey. Collins

spoke later of the two men: 'Ian Buchan knew the game but he was too much

of a theorist, having never played the game at the top level. Johnny on

the other hand had a wealth of experience and understood players more

as he had been successful in his own playing career. A great tactician,

he gave you a job and it was down to the player to make it work.'

afterwards for poor

results and replaced by former Irish international Johnny Carey. Collins

spoke later of the two men: 'Ian Buchan knew the game but he was too much

of a theorist, having never played the game at the top level. Johnny on

the other hand had a wealth of experience and understood players more

as he had been successful in his own playing career. A great tactician,

he gave you a job and it was down to the player to make it work.' the Blues and retained his international place, scoring 3 times in six

appearances, though defeat in Portugal in June 1959 seemingly marked the

end of his Scotland career, as he lost his place thereafter.

the Blues and retained his international place, scoring 3 times in six

appearances, though defeat in Portugal in June 1959 seemingly marked the

end of his Scotland career, as he lost his place thereafter. of

effort and football entertainment.'

of

effort and football entertainment.' told me I was not the player I used to be.

I was not happy and told him so. I'd been the best Everton player that

day and I'd got a rollicking. I knew that my days were numbered.'

told me I was not the player I used to be.

I was not happy and told him so. I'd been the best Everton player that

day and I'd got a rollicking. I knew that my days were numbered.' Goodison the following morning, with two

of our directors, to open negotiations. I spent an hour with Bobby after

training and he told me in no uncertain terms that he felt that he still

had a lot to offer as a First Division player, didn't fancy going to a

club with one foot in the Third. We left it that he would think it over

for a couple of days and get back to me. But as we headed home, I decided

to have another chat with him. I remember, we arrived at his house at

2 pm and waited in the car no less than five hours before he turned up.

We didn't leave until 2.30 am the next morning, but by that time, Bobby

had agreed to join us.'

Goodison the following morning, with two

of our directors, to open negotiations. I spent an hour with Bobby after

training and he told me in no uncertain terms that he felt that he still

had a lot to offer as a First Division player, didn't fancy going to a

club with one foot in the Third. We left it that he would think it over

for a couple of days and get back to me. But as we headed home, I decided

to have another chat with him. I remember, we arrived at his house at

2 pm and waited in the car no less than five hours before he turned up.

We didn't leave until 2.30 am the next morning, but by that time, Bobby

had agreed to join us.'