Part

1 An appreciation - Part 3 From Sweden to Liverpool

- Part 4 Back from the dead - Part

5 End of the line

Part

1 An appreciation - Part 3 From Sweden to Liverpool

- Part 4 Back from the dead - Part

5 End of the line

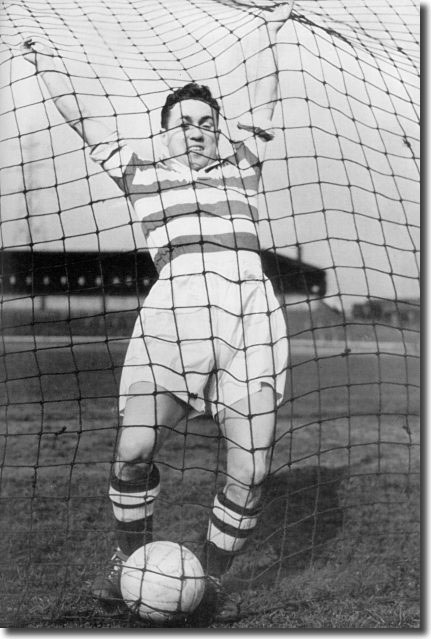

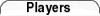

Bobby Collins was one of post-war football's biggest names, bursting

to prominence with Glasgow Celtic in 1949 and becoming one of their favourite

sons. He enjoyed almost a quarter of a century as a professional player,

the first decade of which was in Glasgow, and he achieved legendary status

for his never say die approach.

Born Robert Young Collins in Glasgow on 16 February 1931, he was the

eldest of six children and followed his local club, Third Lanark, as

a boy, often squeezing under the fence to see them play accompanied

by brother Davie.

He was a football fanatic from the very first, recalling later: 'I was

really influenced by players of the era and among a host of Scots we cheered

on were the likes of Jimmy Delaney, Billy Liddell, Archie Macauley, Jimmy

Caskie and two players who went on to manage at the highest level, Bill

Shankly and Matt Busby. England were spoiled for choice and over the years

I saw Eddie Hapgood, Stan Cullis, Joe Mercer, Stan Matthews, Frank Swift,

Raich Carter, Jimmy Hagan and Tommy Lawton display their skills. I played

at every opportunity and growing up I loved hearing about the likes of

Hughie Gallacher, Alex James and Jimmy McMullan who proved that height

did not matter if you are good enough.'

Collins was always on the short side, but never let that deter him,

compensating big style with his football talent and sheer guts. Both

Everton and Celtic chased his signature and the Merseysiders offered

his Pollok club a £1,000 transfer fee. The 17-year-old initially agreed

to the deal, but quickly changed his mind when he heard that Celtic

manager Jimmy McGrory was after him and signed on as a part timer at

Parkhead in 1948 for a weekly wage packet of £8.

The Glasgow giants were among the cream of British football, with 19

Scottish league titles and 15 Scottish Cup wins to their credit since

their formation in 1888. That success was in the past, though, and Celtic

were in a barren spell with only two championships in twenty years, as

arch rivals Rangers eclipsed them, winning the title eleven times over

the same period. Collins may have been joining a footballing super power,

but he did so at one of the lowest points in their history.

Jimmy McGrory had been appointed by club chairman Bob Kelly to bring

back the glory times. He was a Celtic legend in his playing days and

took over from Jimmy McStay in 1945, intent on reviving the club's fortunes.

Bobby Collins was pitched hopefully into this maelstrom of under achievement

as a highly promising 18-year-old. He made his first team debut on 13

August 1949 in a League Cup clash with Rangers. 71,000 Parkhead supporters

saw the youngster perform admirably on the right wing, tormenting Rangers

veteran Jock Shaw.

back to top

Collins: 'I remember going through the middle and Willie Wood fouled

me and we got a penalty. He moaned like hell, but he clipped me. Fortunately,

we won 3-2 and I was never out of the team thereafter. When Celtic played

Rangers you simply had to win and it didn't matter how. If you didn't

win then you knew you wouldn't be able to go out for a while!'

He became an automatic choice, winning rave reviews after his first League

goal, the winner in a 3-2 victory over Hearts. John Jessiman of the Sunday

Express: 'Little Bobby Collins, game as a pebble, built like a Brencarrier,

and in his element at inside-right, crashed home a picture opportunist

goal, fired first time. Away up on the terracing behind the goals, out

flew the green scarves. He brings back to Celtic, this boy, the immortal

fire of Patsy Gallagher. His idea of progress is the shortest way through

… the technique of the electric drill! When he was not hurling himself

at the entire Hearts defence he was back defending. That was Patsy's way.

After the Collins winner, the roar from the Parkhead faithful went on

for five minutes. No wonder!'

He enjoyed a fine debut season, scoring seven League goals, though

Celtic trailed in fifth. Nevertheless it was the club's best finish

since the war. 1951 saw the club slip to a seventh place finish, though

Collins' 15 goals made him top scorer, and included a hat trick in a

6-2 win against East Fife. There was also a first trophy since 1938

as they captured the Scottish Cup. Collins was ever present in the Cup

run, helping the Celts beat Motherwell 1-0 in the final before a 132,000

capacity crowd.

As Collins turned 20, he was making his name as one of the brightest

young stars in Scotland. He recalled later: 'My early games for Celtic

went well and I soon settled into the team's pattern of play … I was expected

to play as a link man in attack as well as a striker who had to get his

share of goals. It was a challenge, but if the manager thought I was capable

of playing in that role then that was fine by me.

'There was no over complication in tactics. Talk never centred on 4-2-4,

4-3-3, diamond formations or sweeper systems, we believed in attacking

football. That was our style of play. If we were on the attack we'd have

five forwards and two wing-halves looking for opportunities and supporting

each other. If we were on the defensive we'd track back to support our

defenders.

'Of course, we had players who could control a game; intelligent footballers

like Bobby Evans, Willie Fernie, Charlie Tully and John McPhail, and with

players of this calibre in the side changing tactics came natural to us

and we were able to adapt. If we had to battle we could and if we were

able to play our natural game we did.'

Collins' outstanding club form caught the eye of the Scotland selectors

and he was called up to the full international squad in the autumn of

1950. Injury forced his withdrawal from a fixture with Switzerland,

but he made his full debut soon afterwards, at Cardiff against Wales

on 21 October 1950. Bobby laid on a cross for Billy Liddell to head

home spectacularly en route to a 3-1 victory. Collins retained his place

for home matches with Northern Ireland, a 6-1 triumph with Billy Steel

scoring four, and Austria. The latter game brought a depressing landmark

with a 1-0 defeat leaving the Scots as the first home international

nation to lose on their own turf to overseas opposition. The setback

prompted a radical rebuilding programme, and it was four and a half

years before Collins regained a place.

Despite winning the St Mungo Cup competition in the autumn of 1951 by

beating Aberdeen in a Hampden Park final, Celtic again finished no better

than mid-table in 1952. They had a bunch of outstanding individuals, including

Collins and the mercurial Charlie Tully, but could not function consistently

as a team, trailing in a hugely dispiriting ninth in an up and down campaign.

The season did have a more positive undertone, though, as Celtic welcomed

a new arrival who was to have a fundamental impact on the club, heralding

a revival in their fortunes.

Jock Stein, a gangling defender, was plucked from the obscurity of Llanelli.

He hailed from a fiercely Protestant family and was approaching 30 when

he arrived at Parkhead in December 1951. He was disowned by his Rangers-loving

father and the move created genuine controversy as he crossed Glasgow's

yawning sectarian divide.

Stein had never pulled up any trees, but Celtic scout and reserve team

trainer Jimmy Gribben was convinced enough of his potential to seek him

out when the Celts required defensive reinforcements, as recalled by Archie

MacPherson in his biography of the Big Man:

'It is not entirely clear what had been retained on the retina of Gribben's

mind's  eye

about Stein. Adam McLean, Stein's [Albion] Rovers colleague, has his own

view: "I remember one night we played a reserve game at Celtic Park.

Celtic had fielded [John] McPhail at centre-forward and he was a handful,

as you would know. Well, Jock never gave him a kick at the ball. He out-headed

McPhail, who was good in the air. All right, it was just a reserve game,

but the way Stein played that night he must have caught somebody's eye."

But perhaps even more significant was a game played by Rovers at Celtic

Park in January 1949 when they played for an hour with only ten men. They

were well beaten in the end, 3-0, but it could have been worse and their

defensive performance received wide praise, the Sunday Post identifying

Stein as one of the "heroes". The Sunday Mail noted that

"pivot Stein, along with Muir and English, looked as confident as

if the score had been reversed." That game would possibly have registered

on any football shrewdie like Gribben.

eye

about Stein. Adam McLean, Stein's [Albion] Rovers colleague, has his own

view: "I remember one night we played a reserve game at Celtic Park.

Celtic had fielded [John] McPhail at centre-forward and he was a handful,

as you would know. Well, Jock never gave him a kick at the ball. He out-headed

McPhail, who was good in the air. All right, it was just a reserve game,

but the way Stein played that night he must have caught somebody's eye."

But perhaps even more significant was a game played by Rovers at Celtic

Park in January 1949 when they played for an hour with only ten men. They

were well beaten in the end, 3-0, but it could have been worse and their

defensive performance received wide praise, the Sunday Post identifying

Stein as one of the "heroes". The Sunday Mail noted that

"pivot Stein, along with Muir and English, looked as confident as

if the score had been reversed." That game would possibly have registered

on any football shrewdie like Gribben.

'The news of his December 1951 signing for Celtic was greeted by two

distinct groups of people with almost the same degree of incredulity.

Firstly there were the boys from Burnbank Cross whose sectarian solidarity

was as unflinching as it had always been. They found it hard to comprehend.

Had Stein turned up at the Cross blind drunk and ranting against the evils

of gambling, it would not have caused as great a stir as the news that

he was about to don a green and white jersey. As Harry Steele admitted,

Stein became an outcast. "He lost a lot of pals overnight when he

signed for Celtic. 'Turncoat' was about the kindest thing they said about

him. After a wee while his name just wasn't mentioned at the Cross. And

although he was in and around Burnbank for a long while he never came

back down amongst us to stand and have a blether."

'Then there was the Celtic supporters' reaction. To understand how they

felt you have to understand the state Parkhead was in at that time. Since

the war the club, which enjoyed massive support, had struggled to win

anything … A measure of their inadequacies and the disillusionment of

their supporters came in season 1951/52 when for the first time in 80

years they lost a Scottish Cup replay, on this occasion to Third Lanark

who had beaten them 2-1 at Cathkin. This underlined not only an apparent

lack of ability but the almost spiritless surrender of the only major

trophy they had won in fifteen years, outside the St Mungo Cup. It represented

staggering underachievement for a club that moved whole armies around

the country in its support. Even worse was the fact that they were no

longer the major challengers to Rangers, having been replaced by Hibernian:

since the end of the war the pendulum of success had swung between Ibrox

and Easter Road where the Famous Five Hibs forward line was playing the

kind of football Celtic themselves had always aspired to.

'When Stein joined Celtic, the club had a League record that made their

aficionados wince when they were forced to consider it. They were in twelfth

position in a sixteen-club league with a record of ten points from eleven

matches (three wins, four draws and four defeats). The pain became almost

unbearable, dissent grew thick on the ground, and the supporters wanted

a positive and creative sign from the board that they knew what they were

doing and where they were heading. What they were being informed about

now was that the club had signed a little-known player from a little-known

town in a little-known league in a country that was addicted to a game

where the ball is shaped like an egg. It was not an acquisition likely

to win friends and influence people. If there was incredulity at Burnbank

Cross and its environs, then you might say that on the other side of the

sectarian divide many of the Celtic support were stricken with increased

anxiety and were struggling to make sense of it all.

back to top

'The manager who greeted Stein and was pictured beside him as he signed

on was one of the most self-effacing men in Scottish football, Jimmy McGrory.

His constant geniality, the gentle and polite manner with which he seemed

to exist within the maelstrom of Old Firm politics and his dignified bearing

stood in sharp contrast to the autocratic Kelly. When you met McGrory

inside Celtic Park, nursing his pipe constantly like a life-support system

and invariably greeting you with a broad smile, and didn't know who he

was, you could have mistaken him for some pleasant grandfather who had

been sent in to wait for a ball to be autographed in the dressing room.

According to Sean Fallon, the Celtic captain at that time, McGrory's team

talks hardly evoked the tone of the Gettysburg Address. "It's going

to be a hard game today, lads," was about as much he could summon

up.

'So Kelly was the dominant figure, even when it came to selecting the

team. John McPhail, years after he left Celtic, told me that in those

days there was a specific ritual when it came to away games. "What

would happen when we were away from home is that Bob Kelly and Jimmy McGrory

and maybe another director or two would go into the toilet in the dressing-room

and shut the door. We would all sit around waiting for the team announcement.

Out they would come, and Jimmy would read out the names. That was it.

Just the names read out and then you got on with it. There was one day

when I knew in my bones I wouldn't be playing. It was a cert. I had been

playing badly and I was putting on weight. Well, that day, to my utter

surprise, Jimmy read out my name in the team. I noticed then the chairman

hadn't come out of the toilet and I discovered later that he was answering

the call of nature for he had something wrong with his stomach that day.

The team Jimmy read out wasn't the one they had selected in the toilet.

He made a mistake naming me, and since the chairman wasn't at his elbow

there was nobody there to correct him. I had stripped off like everybody

else and was out on the park before Bob Kelly realised it. Celtic won

that day, by the way, and I got to play because of the chairman's diarrhoea.

I know it sounds incredible now, but that was the way the club was run

in those days."'

Jock Stein's merits were plain enough to Bobby Collins, who offered his

endorsement: 'Some supporters threatened to boycott games if he was selected,

which was incredible. Jock may have been turning professional at the age

of 28, but you had to give him a chance. Fortunately the manager did give

him an opportunity and Jock soon settled into the team.

'Jock read the game well, could spot danger and opportunities quickly

and as a player we all respected him, but it was as a captain that you

really saw his credentials. He was always encouraging and demanding more

effort, and got it. Nobody escaped praise when it was warranted or a sharp

word where necessary.'

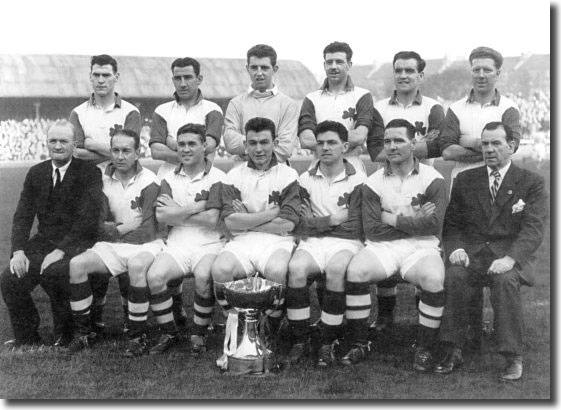

Steadied by the influence and leadership of Stein, Celtic won the Coronation

Cup in 1953, defeating Arsenal, Manchester United and Hibs on the way.

Collins' goal direct from a corner was the only score in the game against

the Gunners and he remained one of the club's most regular goalscorers,

despite their inconsistency.

1954 saw Celtic finally recapture both consistency and the championship.

They began the season tentatively, though Collins was on fine form. He

became one of the few players ever to manage a hat trick of penalties

in the same game, helping Celtic beat Aberdeen in September. The Glaswegians

spent most of the season in the wake of table topping Hearts and it seemed their chance had gone when they lost 3-2 at Tynecastle in February, leaving

the Edinburgh club seven points clear at the top.

their chance had gone when they lost 3-2 at Tynecastle in February, leaving

the Edinburgh club seven points clear at the top.

However, Celtic had become a resolute team under Stein, and they won

their final nine games on the bounce to end the season champions by five

points, securing a first title for 16 years.

Collins played in all but five games, though an injury suffered against

Hearts meant that he missed the Scottish Cup final, which saw his club

secure the Double by beating Aberdeen with a Sean Fallon goal.

Collins: 'It was really disappointing to miss out on the Cup final, but

I was delighted for the lads. I'd been injured for around ten weeks, but

after battling back to fitness I'd hoped to be in contention. It wasn't

to be though, and I couldn't complain because the team had played well

and reached the final without me. I had to wait for my chance to get back

into the first XI. I was just delighted to play and score in the final

League game two days after the Cup final and enjoyed all the celebrations.

Our fans were ecstatic. It was a wonderful achievement because the team

had been in inconsistent form for a number of years so it was fantastic

to put a run together. Overcoming Hearts was a great effort by the squad.'

Celtic failed to defend either trophy in 1955, losing out to Aberdeen

in the title race, though they ended the season with more points than

the year before. They reached the Scottish Cup final but could only draw

1-1 with Clyde.

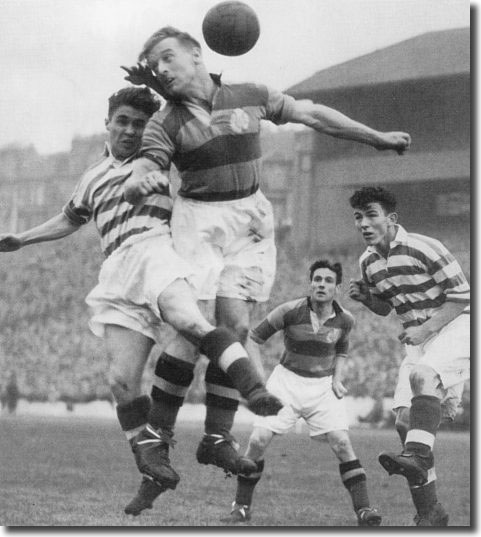

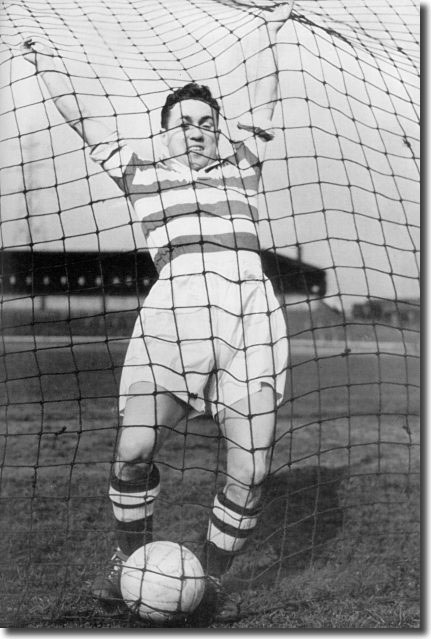

Archie MacPherson: 'Celtic should have had the Cup won in the first half

hour of the game when they swamped the Clyde defence. Bobby Collins was

demonstrably the most influential player up front, and like all wee men

who perform like that he had the crowd backing him, like a favourite jockey

leading the pack. He was also throwing his small but sturdy frame around

and was particularly heavy on one occasion with Clyde's South African

goalkeeper Hewkins. That was significant for what was to occur later.'

Jimmy Walsh put Celtic ahead after 38 minutes and it was expected that

the goal would be decisive. However, two minutes from time a corner from

Clyde's Archie Robertson was blown into goal by the Hampden swirl and

the Bully Wee had snatched an unlikely draw.

Archie MacPherson: 'What … occurred thereafter was to trigger in Stein's

mind the need for inviolate managerial control over a team. Those next

few days before the replay, particularly the team announcement for the

game just before kick off, preyed on his mind in the days leading up to

his decision to go back to Parkhead as manager in 1965. He never forgot

it … what happened next was a shambles. Collins was dropped. Mochan, who

had scored nine goals in seventeen league matches that season, was kept

in the stand. Walsh's position was changed unaccountably from inside-left

to the right wing. McPhail, who had played centre, was moved to inside-left

and Sean Fallon, famed for his rumbustious style, was brought back after

a long spell of injury to lead the line. The changes were in themselves

odd, but the dropping of Collins in the light of what was to happen was

simply a provocation to the Celtic legions. The wee man had certainly

indulged in uncompromising challenges in the first game and it was clear

that Bob Kelly had taken a dim view of his demeanour, so Collins was not

to play.

'Stein never said an unkind word about Bob Kelly, that I know, but he

as much as admitted to me that he had witnessed manager Jimmy McGrory

being starkly ignored, ridden over and eventually, in terms of the loss

of the replay, ultimately humiliated … Harry Haddock, Clyde's cheery and

mobile full-back captain, read out the Celtic team in the Clyde dressing-room

with astonishment and with a renewed feeling of confidence. It was not misplaced. On a miserably wet evening, with only 68,831 in attendance

… Tommy Ring scored the only goal for Clyde seven minutes after half-time.'

misplaced. On a miserably wet evening, with only 68,831 in attendance

… Tommy Ring scored the only goal for Clyde seven minutes after half-time.'

Collins was devastated by his exclusion, saying: 'It was really disappointing.

I wonder in the modern game how many chairmen would have taken that decision.

I was not happy.'

back to top

His mood was lifted by a recall to the Scottish ranks as the season drew

to a close.

The Scots had enjoyed a pretty dire couple of years, losing both games

in the 1954 World Cup finals, including a 7-0 reverse against reigning

champions Uruguay. A disastrous 7-2 defeat against England at Wembley

in 1955 had concluded a depressing run of just four victories in 15 games.

The humiliation against the Auld Enemy prompted a major overhaul, with

9 changes for the following match, which brought a 3-0 victory against

Portugal. Collins was recalled for the next game against Yugoslavia in

Belgrade on May 15.

David Saffer: 'In a battling display the Scots twice came from behind

to draw 2-2 and were somewhat unfortunate not to win when they were denied

a last-minute penalty. Four days later national pride was restored after

a thumping 4-1 win in Vienna.

'Played four days after Austria had gained full independence, after concluding

a peace state treaty with wartime occupying powers, the atmosphere was

hostile throughout. Scotland controlled the match for long periods, scoring

in the opening and closing minutes of the game. Clearly frustrated, and

no doubt in mind of the historical importance, home players engaged in

fist fights throughout the game, and twice hundreds of fans invaded the

pitch. The only surprise was that only one Austrian player was sent off,

Barschandt, for persistent fouls on Scotland captain Gordon Smith. Smith

was escorted off the field at the end by police, as was the Scottish team

coach when they left the ground.'

Alec Young of the Scottish Daily Mail: 'This was a great Scottish

victory. No team has been asked to do more and no team had made such a

magnificent response as our lads did in this amazing "Battle of Prater

Stadium". In the midst of all the excitement of this clash it was

a matter of light relief to see Bobby Collins, a lion heart terrier, repeatedly

being pushed aside, yet repeatedly coming back again and even squaring

up to six footers when as often happened football science was forsaken

for the fistic arts.'

Collins retained his place for the final tour match, which the Scots

lost 3-1 to Hungary. Nevertheless, it had been a splendid return for Collins,

who declared: 'It was wonderful to be back and part of a really successful

tour, which gave us tremendous confidence for the battles ahead.'

1955/56 brought more disappointments in the league as Celtic trailed

in fifth behind champions Rangers. They reached the Scottish Cup final

once more, but yet again Collins missed out on the big day, this time

with a knee injury, as Celtic lost 3-1 to Hearts. Collins: 'I could barely

believe it when I was ruled out of a major final for the third year running.

Losing was bad enough, sitting on the sidelines unable to help made it

even more frustrating.'

There was some compensation, though, with two Collins goals helping Celtic

beat Rangers 5-3 in a Hampden replay to win the Glasgow Cup.

Collins sustained a broken leg in a league match against Dundee and missed three months of the 1956-57 season, though he scored

a goal as Celtic beat Partick Thistle 3-0 to win the League Cup.

Dundee and missed three months of the 1956-57 season, though he scored

a goal as Celtic beat Partick Thistle 3-0 to win the League Cup.

He continued to feature for the international team and was a key part

of Scotland's plans for World Cup qualification. Their campaign started

with a clash against Spain at Hampden on 8 May 1957.

The Spaniards had Alfredo Di Stefano in their ranks, but the Scots had

the spirit and the goals of Jackie Mudie, whose hat trick was the telling

factor in a 4-2 triumph. Scotland built on the good start by battling

back from a goal down to win 2-1 in Switzerland. Collins' 72nd minute

decider was his first international goal.

Even better was to come as Bobby contributed a brace when Scotland beat

world champions West Germany 3-1 in a friendly in their own back yard.

Douglas Ritchie: 'Scott and Ring sizzled the ball from wing to wing and

the outside-left turned his final cross low in front of goal. Szymaniak

slipped going to clear and Collins darted in to score. Collins struck

again after 56 minutes. The wee Scot waltzed past a defender and sent

in an atomic shot that almost ripped the roof of the net. The tiny knot

of sore throated Scots in the vast crowd loved that one and even the Germans

couldn't help cheering.'

A 4-1 reverse in the return in Spain was a body blow, but the Scots were

still in pole position and well set for a place in the finals. By beating

the Swiss 3-2 at Hampden in November 1957, Scotland confirmed their place

in the 1958 tournament in Sweden, and Bobby Collins was set to prove his

worth on the biggest stage of all.

He set off for the finals after an outstanding season for Celtic, notching

a career best 19 goals in 30 League games as the Celts finished third,

a distant 16 points behind champions Hearts. The high point came with

an amazing victory over Old Firm rivals Rangers in the Scottish League

Cup final. Bobby sealed the place in the final with a man of the match

performance against Clyde in the semis.

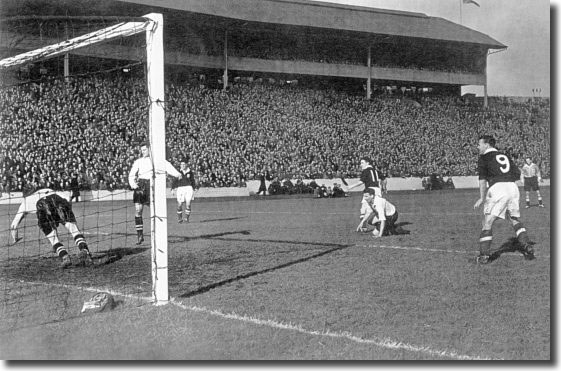

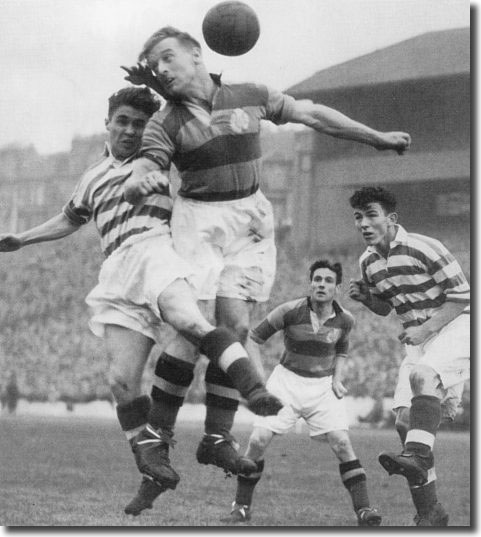

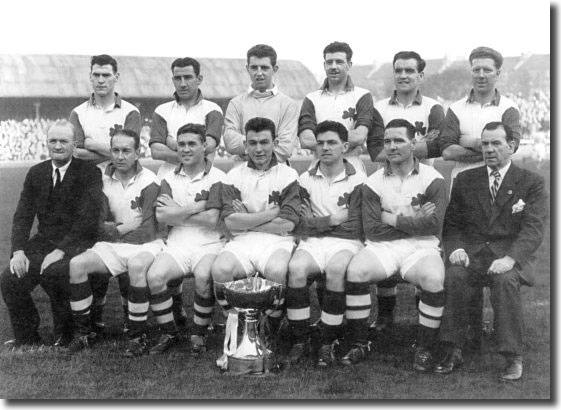

The final was to go down in Celtic folklore as the ultimate humbling

of Rangers. Collins recalls the 7-1 thrashing:

'It was a dream of a game for us, but it must have been a nightmare for

Johnny Valentine. Rangers had signed the big centre-half from Queens Park

at the start of the season but he simply hadn't clicked. On this day at

Hampden, I don't know if Valentine had no faith in George Niven or Niven

had no faith in Valentine, but ultimately they had no faith in themselves,

something you can sense very quickly on a football field, and inevitably

the game became a rout.

'Valentine was covering Billy McPhail and McColl and Davis were covering

Valentine, which left three of our men with the freedom of Hampden. Rangers'

defenders were standing on their heels when Sammy Wilson slammed home

goal number one in 22 minutes. They were standing on their heads when

Neilly Mochan rammed in number two just before half time. They say Rangers'

mistakes in the first half were because of too much sun in their eyes, but the truth is there had been too much Celtic in their

eyes!

in their eyes, but the truth is there had been too much Celtic in their

eyes!

'By the time we came out for the second half we had sensed that 'something'

was on. We could scarcely put a foot wrong. The ball sped from toe to

toe. Donnelly to Fernie, Fernie to Tully, Tully to me, over to Mochan

and so on. Just to vary things, the ball often stopped at Willie Fernie.

Willie kept the entertainment going. And every now and then we slotted

in another goal.

'Billy McPhail took a joint gift from Niven and Valentine to make it

three. A good flying header by Billy Simpson reduced our lead, but somehow

it didn't seem to matter. We just carried on, playing our football and

we scored another four.

'Twice I hit the bar with 30-yard free kicks. McPhail nodded in to make

it 4-1. Neilly Mochan duffed a kick, yet still saw his shot enter the

net. Billy McPhail stepped in to complete his hat trick, then with the

last kick of the game, Willie Fernie got his own souvenir of the occasion.

Shearer fouled McPhail … penalty! Fernie took the kick. The ball landed

low in the net. The time up whistle blew.

'It was the biggest ever victory to be chalked up in a competitive Old

Firm game and as a special favour, the Celtic players were allowed to

keep their jerseys as a souvenir of the great day.'

It was a truly memorable occasion for Celtic and Bobby Collins and the

perfect springboard for his footballing summer.

Part 1 An appreciation - Part

3 From Sweden to Liverpool - Part 4 Back from

the dead - Part 5 End of the line

back to top

Part

1 An appreciation - Part 3 From Sweden to Liverpool

- Part 4 Back from the dead - Part

5 End of the line

Part

1 An appreciation - Part 3 From Sweden to Liverpool

- Part 4 Back from the dead - Part

5 End of the line  eye

about Stein. Adam McLean, Stein's [Albion] Rovers colleague, has his own

view: "I remember one night we played a reserve game at Celtic Park.

Celtic had fielded [John] McPhail at centre-forward and he was a handful,

as you would know. Well, Jock never gave him a kick at the ball. He out-headed

McPhail, who was good in the air. All right, it was just a reserve game,

but the way Stein played that night he must have caught somebody's eye."

But perhaps even more significant was a game played by Rovers at Celtic

Park in January 1949 when they played for an hour with only ten men. They

were well beaten in the end, 3-0, but it could have been worse and their

defensive performance received wide praise, the Sunday Post identifying

Stein as one of the "heroes". The Sunday Mail noted that

"pivot Stein, along with Muir and English, looked as confident as

if the score had been reversed." That game would possibly have registered

on any football shrewdie like Gribben.

eye

about Stein. Adam McLean, Stein's [Albion] Rovers colleague, has his own

view: "I remember one night we played a reserve game at Celtic Park.

Celtic had fielded [John] McPhail at centre-forward and he was a handful,

as you would know. Well, Jock never gave him a kick at the ball. He out-headed

McPhail, who was good in the air. All right, it was just a reserve game,

but the way Stein played that night he must have caught somebody's eye."

But perhaps even more significant was a game played by Rovers at Celtic

Park in January 1949 when they played for an hour with only ten men. They

were well beaten in the end, 3-0, but it could have been worse and their

defensive performance received wide praise, the Sunday Post identifying

Stein as one of the "heroes". The Sunday Mail noted that

"pivot Stein, along with Muir and English, looked as confident as

if the score had been reversed." That game would possibly have registered

on any football shrewdie like Gribben. their chance had gone when they lost 3-2 at Tynecastle in February, leaving

the Edinburgh club seven points clear at the top.

their chance had gone when they lost 3-2 at Tynecastle in February, leaving

the Edinburgh club seven points clear at the top. misplaced. On a miserably wet evening, with only 68,831 in attendance

… Tommy Ring scored the only goal for Clyde seven minutes after half-time.'

misplaced. On a miserably wet evening, with only 68,831 in attendance

… Tommy Ring scored the only goal for Clyde seven minutes after half-time.' Dundee and missed three months of the 1956-57 season, though he scored

a goal as Celtic beat Partick Thistle 3-0 to win the League Cup.

Dundee and missed three months of the 1956-57 season, though he scored

a goal as Celtic beat Partick Thistle 3-0 to win the League Cup. in their eyes, but the truth is there had been too much Celtic in their

eyes!

in their eyes, but the truth is there had been too much Celtic in their

eyes!