|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

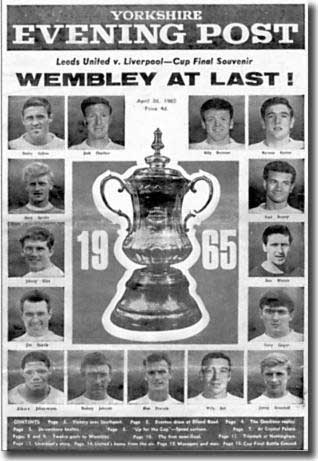

FA Cup final after extra time - Wembley Stadium - 100,000

Scorers: Bremner

Liverpool: Lawrence, Lawler, Byrne, Strong, Yeats, Stevenson, Callaghan, Hunt, St John, Smith, Thompson

Leeds United: Sprake, Reaney, Bell, Bremner, Charlton, Hunter, Giles, Storrie, Peacock, Collins, Johanneson

The Yorkshiremen retained one final chance of silverware, having won

their way through to an FA Cup final appearance on 1 May against reigning

champions Liverpool. It was the first time that United had come near a

sniff of FA Cup glory, and, with the Anfield club never having won the

Cup, it was certain there would be a new name on the famous trophy. Liverpool had surrendered their league title meekly, trailing in a disappointing

7th, 17 points behind Leeds, but they had done well in their European

Cup debut season. They beat FC Cologne on the toss of a coin in a quarter

final play off, and now faced mighty Inter Milan at Anfield three days

after the FA Cup final. Under legendary manager Bill Shankly, the Anfield club were emerging

as one of the new powers of the English game and would be stern opponents.

Their run to the Cup final had seen them defeat West Bromwich Albion,

Stockport County, Bolton Wanderers, Leicester City and new League Cup

winners Chelsea. Leeds had the fortune to be drawn against lower division opponents Southport,

Shrewsbury Town and Crystal Palace on the way to Wembley, although they

had also ousted 1963 champions Everton and Manchester

United, requiring replays on both occasions. Liverpool's only absentee was England wing-half Gordon Milne, who had

damaged his knee ligaments over Easter. Strangely, Milne's father had

missed the 1938 final for Preston North End when he broke a collarbone

a fortnight before the final against Huddersfield Town. Coincidentally,

Leeds were the first Yorkshire club since then to have made it to the

final. It was an enormous disappointment for Milne, whose dynamic, probing style

had been a key feature of Liverpool's season, but offered an unexpected

opportunity for Geoff Strong, who had been signed for £40,000 from Arsenal

six months previously. The rest of Shankly's line-up was much as expected: Scot Tommy Lawrence, 'The Flying Pig', was in goal, 21-year-old Chris

Lawler had ousted Ronnie Moran at right-back and Gerry Byrne was in his

normal place on the left. Gigantic Scottish centre-half Ron Yeats skippered

the side and was supported by young Tommy Smith, sweeping up despite wearing

the No 10 shirt. Willie Stevenson had been a fixture at left-half since arriving from

Rangers for £20,000 in October 1962 and Ian Callaghan was a reliable performer

on the right flank. Liverpool's key threat, though, lay with their three

other forwards: Roger Hunt, Ian St John and Peter Thompson. England striker

Hunt had been the Reds' goalscoring talisman ever since arriving at the

club as a 20-year-old in May 1959; the £37,500 signing of Scottish international

St John from Motherwell was one of Shankly's greatest ever deals; Thompson

had so impressed with his wing play for Preston in an FA Cup clash with

the Reds in 1962 that Shankly returned to capture him a year later. For Leeds, Albert Johanneson,

Jim Storrie and Willie

Bell had all recovered from injury and were available for selection.

Their inclusion was never in serious doubt, although it meant that the

promising Terry Cooper, who had done so well in covering for both Bell

and Johanneson in the second half of the campaign, missed out. Gary Sprake, Paul Reaney, Jack Charlton

and Norman Hunter were automatic choices in a cast iron defence, while

Billy Bremner, newly installed Footballer of the Year Bobby

Collins and Irish winger Johnny Giles made up a diminutive, but redoubtable

midfield combination. Former England World Cup centre-forward Alan

Peacock completed the line up after fully recovering from a serious

knee injury that had kept him out of the side until the end of February. While Leeds were generally rated narrow favourites, there were far more

red colours in the Wembley crowd than white, and Don

Revie's still relatively unproven young side was apprehensive as they

came out of the tunnel. Bill Shankly turned to his old Merseyside adversary,

Bobby Collins, and asked him how he was. Collins responded, "I feel awful,"

capturing the mood of his team. Collins: 'You've got little chance of winning at Wembley unless most

of your players have played there previously, and know what to expect.

Leeds allowed themselves to be caught up in the hullabaloo surrounding

the final and the youngsters especially found it very difficult to relax.

On the Friday a week before the Cup final, we played at Sheffield; we

left Sheffield on the Monday to go to Birmingham, then went to London

to prepare for the final on the Wednesday. So the players had slept in

three different beds in five days, and allowed this to have an unsettling

effect. 'Mind you, despite being one of Leeds' most experienced players, my form

at Wembley left a lot to be desired, too! I don't know why, but this has

always been a bit of a jinx ground for me; the prospect of playing at

Wembley has never thrilled me as it does most fellows.' The skipper also chose to forsake the new socks most of his teammates

wore: 'I preferred woollen to nylon because I felt more comfortable; the

only trouble was that with constant washing they turned yellow. Throughout

the campaign I'd worn my yellowing socks and for the final we had bright

new white ones, which I was not happy about. After explaining this to

Don, being incredibly superstitious himself, he insisted I wear my old

discoloured socks that had served me so well during the season. I thought

that would be the end of the matter, but the media picked it up and even Fellow Scots Collins and Ron Yeats came forward for the toss, and there

were fully twelve inches between the heights of the giant and the midget.

The United captain called correctly, opting to change ends and allow the

Reds to kick off in overcast conditions. Almost from the start, the pattern of play was established. Liverpool, battle hardened from three years in the top flight and twelve

months of European competition, were assured, fluid and flexible. They

played within themselves and were always more concerned with the certainty

of possession than the gamble of a panicky forward pass. Their formation

alternated smoothly between 4-4-2 and 4-2-4, founded on the calm midfield

platform given them by the control of Strong and Stevenson. Their four

forwards were in constant shuttle between midfield and attack, offering

width and the constant comfort of a short square pass. Their movement

allowed them to develop clear and precise passing triangles round pedestrian

opponents. The speed and ease with which St John and Hunt combined in

slick and smooth one-twos left Charlton and Hunter nonplussed and slack

jawed. United, in contrast, were as rigid and static as the stance of Alan Peacock,

constantly outthought and outmanoeuvred. Their defence, tantalised by

Liverpool's patterns and movement, insisted on lying deep, entrenched

constantly on the edge of their penalty area; Bremner, Giles and Collins

clustered tightly in midfield, content to move as a unit but with only

the long through ball as an outlet; Johanneson, strangely out of sorts,

and Storrie, rendered immobile and ineffective by early injury, made only

fitful contributions out wide, leaving Peacock alone and exposed down

the middle, dominated almost completely by the looming Yeats. While the midfield trio had their moments, they were either caught too

far upfield, leaving Liverpool an acre of room to exploit and their back

four dreadfully exposed, or too remote from their forwards to bring them

into the game in any meaningful way. It was dreadfully disappointing and Leeds looked one dimensional and

emasculated. For Albert Johanneson, the stage had been all set for him

to deliver the sort of performance that Goalkeeper Gary Sprake was the one Leeds player to shine, though Billy

Bremner ran his heart out in the United cause. Sprake saved countless

efforts and kept his team in the contest far longer than they deserved

with one of his greatest games. Rob Bagchi and Paul Rogerson in The Unforgiven talk of the club's

preparations for the day, and the less than ideal impact on the players:

'This was Revie's special time, the time he loved most. Secluded with

his players in the Selsdon Park Hotel near Croydon, … he could escape

the distractions of running the whole club and indulge himself in organising

his famously innocent diversions of indoor bowls and dominoes. But on

this occasion it was counter productive. The consensus among his squad

was that they should have been allowed to go home instead of being holed

up in a Surrey hotel for days on end with nothing to do. Bored and out

of sorts, they became over focused on the technicalities of their game

plan and overwhelmed by the magnitude of the task ahead.' Jack Charlton: 'We went to stay the few days before the Cup final at

a hotel near London … I remember playing a little five-a-side game on

the Friday. Norman Hunter volleyed the ball, and it hit Bobby (Collins)

on the face, making his nose bleed a little. It was clearly an accident,

not deliberate or anything. Then the game restarted, and when Norman got

the ball Bobby just flew at him. It was obvious Bobby meant to do him

harm. I yelled, "Norman!" - and he looked up and turned just

as Bobby hit him in the middle with both feet. Bobby finished up on top

of Norman, punching him. I yanked him off, and I had to hold him at arms'

length because he started trying to whack me. "Come on, Bobby, calm

down," I said, "we've got a Cup final tomorrow." But that

was Bobby, you couldn't stop him when he got worked up.' The match as a whole fell far short of its billing, but that was unsurprising.

Few teams were better equipped to drive the colour out of an occasion

than Leeds and Liverpool. Both clubs had made their mark on the First

Division with their system and method football, which the physical rigours

of Division Two had demanded. They were spearheading a grim trend in the

English game, as denounced in one quote at the time: 'The leaden football of the first 90 minutes has earned the 1965 Cup

final a reputation as the worst final for years. This is the price the

public must pay for the success it demands. Gates for years have shown

that the fans will not settle for brave losers; they ought not now to

complain of the way victories are won. Leeds 'Like it or loathe it, this was the football that got them there. I am

astonished to find so many surprised at the style and standard of the

play. Almost alone on Saturday, I warned that this method football would

come strange to the taste of many. Too late, the English are finding that

you cannot have the prize without that play. It is like a man swapping

his battered sports car for the efficiency and comfort of a saloon, then

complaining he misses the exhilarating rush of wind in his face.' The opening minutes of the contest were untidy, with the most active

men being the two trainers. In the third minute, Hunter badly injured his ankle in a tackle out on

the left as he nailed his man. Seconds later Collins stamped into a challenge

on Byrne. Play was held up for almost two minutes as Hunter and Byrne

received treatment. At the time, Hunter's looked the more serious problem,

but Byrne suffered the greater damage, recalling later: 'I went in for

a tackle with Bobby Collins. He put his foot over the ball and turned

his shoulder into me. I'd never broken a collarbone before, so I wasn't

aware of what damage had been done straight away. It didn't cross my mind

to leave the field and I played on with my arm dangling motionless by

my side.' The full-back hid his discomfort so well that no one knew until the end

that he had broken a bone. In fact, he gave a wonderful performance, slick

and assured, earning himself the time and space to avoid further damage. Charlton, Bremner and Storrie also required Les Cocker's attention within

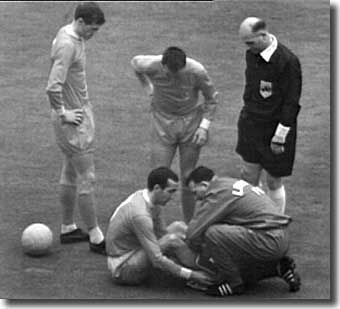

ten minutes of the start. Storrie's damaged left ankle eventually left

him a hobbling passenger on the right wing. Only once in the first 20 minutes did Leeds threaten. Bremner won the

ball and released Johanneson wide on the left. He made some progress and

the overlapping Bell then won a corner, but Peacock's header was aimless

and wide. The telling pass from Bremner was a rarity from United's midfield.

Most of their contributions were long and aimless, pumped down the middle

for the head of Peacock, and easily snuffed out by Yeats. Had his colleagues

learned from Bremner's example, or had Johanneson been more effective

with the little possession he enjoyed, Leeds might have fared better,

but neither came to pass. In stark contrast, St John and Hunt, prompted by the canny control of

Stevenson, cleverly exploited the space in front of United's back four

and carved out decent opportunities. Leeds had to thank Sprake on several

occasions for keeping them in the contest. Rain began to fall heavily after 25 minutes, making the conditions difficult,

but Liverpool continued to have the better of things. Liverpool grew more dominant after the break and came close several times,

forcing Sprake into action time and again. On occasions the United defence

were camped in their own area. Liverpool's slick pass and move game pinned

Leeds back and kept them stretched to the limit of their abilities. Bremner pushed forward in the latter stages as Storrie grew more and

more uncomfortable, and brought some much needed fire, though few opportunities. Liverpool seemed a little tentative, a little too ready to hold possession

as they shifted crablike across the field, but they were always able to

forge an opening. Charlton and Hunter blocked many efforts, and Sprake

was outstanding, but the Reds had enough chances to have won easily. Hunt headed Callaghan's centre over the bar; Charlton blocked a 10-yard

drive from St John; Stevenson fluffed his shot after a free kick bounced

clear; Callaghan fired into the side netting from long range out on the

right before Thompson went even closer after bursting in from the other

wing. Surely, Leeds would concede sooner or later? But they didn't, and somehow they managed to reach 90 minutes with a

blank scoresheet. They had never come close to a goal themselves, despite

all Bremner's urgency, with Peacock, Johanneson and Storrie bystanders,

yet they were proving a durable nut to crack. It was the first time since 1947 that extra-time had been required, and

the way things were going there was a suspicion that there might be the

first replay since 1912, so resolute was the rearguard action from Leeds. United kicked off the extra 30 minutes with Bremner conspicuously leading

the attack and Johanneson now switching wings. Soon the big talking point

was the onset of cramp among the players, and most noticeably Giles, who

after a minute was down on the edge of the Leeds box needing lengthy attention

from Les Cocker. When play restarted with a Liverpool throw in on the right, it seemed Liverpool should have safely seen out time with their possession football,

but Leeds contrived to create their best opening of the day after nine

minutes of extra-time. Giles brought down a lofted Liverpool clearance out on the left touchline,

playing it to Peacock who fed Hunter. The defender, advancing to the edge

of the centre circle, launched the ball into the penalty area for Charlton

to nod it back. The advancing Bremner met the dropping ball perfectly

on the volley and fired it into the open net to his right. Leeds were

back in it, against all expectations. There were no more goals in the first period of extra-time, but Liverpool

launched a number of assaults as play resumed. Sprake saved Strong's shot

from the right hand corner of the penalty area and then Hunter volleyed

clear for a corner when St John got away inside the box. Leeds couldn't

hold out, however, and after six minutes of the second period, Liverpool

regained the lead. Thompson gained possession far out on the Reds' left before playing the

ball infield to Smith, who shipped it on to Callaghan, socks rolled down

to his ankles, on the right flank. He rounded Bell, skipped to the byline

and centred the ball for the plunging St John to net in fine style. Leeds broke back and for once Johanneson made a decent surge only for

Bremner to be flagged up for offside, signalling the end of United's effort. Just afterwards Charlton lost possession to Thompson as he was carrying

forward, and the winger broke away at speed, shadowed by a couple of defenders.

He advanced to the edge of the area and jinked left to create some space,

before letting fly. His shot brought the The tired limbs of the United players could offer no more resistance.

Liverpool saw out the remaining

minutes comfortably to earn their first Cup triumph, sending Leeds back

to Yorkshire with nothing to show for a wonderful season. Billy Bremner: 'Having drawn level, we should have pulled everyone back

into defence and concentrated on getting a draw. We would then have been

able to polish up our game before the replay - I am sure that we couldn't

possibly have played so badly a second time. But that equaliser prompted

us to go for victory, and in doing so, I feel we handed victory to Liverpool

on a plate.' Don Revie promised his players they would be back, telling Bremner: 'Don't

let it worry you, Billy. We will be back and next time you'll be skipper

and we'll win.' But for now his players were alone with their disappointment. Jack Charlton offered this analysis of the defeat: 'What went wrong with

Leeds, the power-and-method team which had made such an impact upon the

First Division all through the season? I think part of the answer was

that we had a lot of youngsters in our side, and the occasion of playing

such a show game as the FA Cup final perhaps overawed some of them. I

believe I'm right in saying that only Bobby Collins and myself had played

at Wembley before - and my experience was limited to one game for England

a few months earlier. Liverpool, on the other hand, had been in the big

time three or four seasons; they were hardened not only to the long grind

of a 42-game First Division slog but inured to the atmosphere of games

like the final, where emotional outbursts by the fans can have such a

tremendous effect upon the players. 'The disappointing thing about the final, I think, was not that we failed

to win - but that we lost so dully. Every player, I believe, wants to

be associated with a classic final … and our display was so out of keeping

with our ability that it really hurt.' Jim Storrie: 'At the finish, the Leeds players felt sorrier for Revie

than themselves. We were sitting with our heads bowed when he came into

the dressing room, and someone said: "We're sorry boss ..."

He replied: "You've run your guts out all season, have nothing to

show for it, and you're sorry for ME? Don't be so bloody daft. Get dressed,

we're going back to the hotel for a booze up."' In the Liverpool dressing room, someone asked Bill Shankly: 'Why do you

think Leeds failed this season?' 'Failed?' Shankly replied incredulously. 'Second in the championship;

FA Cup finalists; ninety per cent of the managers in the English League

pray every night for "failures" like this!' Leeds

United were shock challengers for the League title in 1965 but their remarkable

chase for the championship ended disappointingly. After a formidable showing

on their return to the First Division, the Whites

dropped a point in a 3-3 draw at relegated Birmingham City while Manchester

United beat Arsenal 3-1 at Old Trafford to settle matters, with Leeds

finishing runners up by dint of a much inferior goal average.

Leeds

United were shock challengers for the League title in 1965 but their remarkable

chase for the championship ended disappointingly. After a formidable showing

on their return to the First Division, the Whites

dropped a point in a 3-3 draw at relegated Birmingham City while Manchester

United beat Arsenal 3-1 at Old Trafford to settle matters, with Leeds

finishing runners up by dint of a much inferior goal average. the Duke of Edinburgh noticed them and pointed it out when he was introduced

to the teams before the game!'

the Duke of Edinburgh noticed them and pointed it out when he was introduced

to the teams before the game!' would

take the cause of the black footballer in Britain to fresh heights. He

could have cemented his reputation as one of the most exciting wingers

in the game, but he seemed overwhelmed by the occasion. He was the one

player in the Leeds eleven who could excite crowds, but Liverpool handled

him superbly, with Lawler sitting deep and waiting for the South African

to commit himself. The normal outcome was the ball bouncing loose and

Lawler picking off his man.

would

take the cause of the black footballer in Britain to fresh heights. He

could have cemented his reputation as one of the most exciting wingers

in the game, but he seemed overwhelmed by the occasion. He was the one

player in the Leeds eleven who could excite crowds, but Liverpool handled

him superbly, with Lawler sitting deep and waiting for the South African

to commit himself. The normal outcome was the ball bouncing loose and

Lawler picking off his man. and

Liverpool did not play like this because they were at Wembley. Rather,

they were at Wembley precisely because they play like this.

and

Liverpool did not play like this because they were at Wembley. Rather,

they were at Wembley precisely because they play like this. It

never seemed likely, though, that there would be a goal in a drab first

half.

It

never seemed likely, though, that there would be a goal in a drab first

half. that the break had disturbed United's concentration. Stevenson slipped

through a number of tackles as he danced deftly towards the edge of the

Leeds area. He slid a delightfully incisive through ball to the overlapping

Byrne on the left. The full-back's clipped ball from the byline was met

by a stooping Roger Hunt, who nodded it in to send the Reds' fans into

raptures. The police carried one of their supporters off after he celebrated

a little too enthusiastically.

that the break had disturbed United's concentration. Stevenson slipped

through a number of tackles as he danced deftly towards the edge of the

Leeds area. He slid a delightfully incisive through ball to the overlapping

Byrne on the left. The full-back's clipped ball from the byline was met

by a stooping Roger Hunt, who nodded it in to send the Reds' fans into

raptures. The police carried one of their supporters off after he celebrated

a little too enthusiastically. best out of Sprake, doing wonders

to tip it round the post as he dived to his right.

best out of Sprake, doing wonders

to tip it round the post as he dived to his right.