An

appreciation - Part 2 King Charles -

Part 3 Red Dragon - Part

4 The Italian Job - Part 5 End of an Era

An

appreciation - Part 2 King Charles -

Part 3 Red Dragon - Part

4 The Italian Job - Part 5 End of an Era

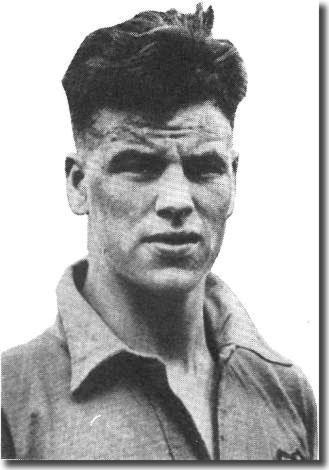

The 1950's had many supreme footballing talents - wing wizards like

Preston's Tom Finney and Stanley Matthews of Stoke City and Blackpool,

the burning, unfulfilled genius of Manchester United's Duncan Edwards,

the cool reassurance of Wolves and England skipper Billy Wright, the

robust Bolton centre forward Nat Lofthouse, but the decade belonged

without question to an awesome lad hailing from the pits and hills of

South Wales.

JOHN CHARLES!

Even today, fully forty years after his peak, the name is whispered

with admiration whenever a list of the greatest ever British talents

is collected together. He rose to being, for a couple of years at the

end of the decade, quite possibly the outstanding football talent on

the planet, adored and feted through most of Western Europe, but especially

so in his adopted home of Turin.

But he came from humble beginnings and developed through unlikely surroundings

in West Yorkshire.

William John Charles was born in Swansea on 27 December 1931. His younger

brother Mel later played alongside him for Wales and had a good career

with Swansea, Arsenal and Cardiff. For youngsters in Wales in those

days, there were only two options - the pit or the pitch and the lad

who was sprouting up as a tall and well built young man had no doubts

about which option he preferred.

He did not consider himself anything special, even though he played

for Swansea Boys before he left school in 1945. He managed to get himself

taken onto the groundstaff of his home town club, Swansea Town, in 1946

as he was approaching his fifteenth birthday. Swansea had joined the

Third Division of the Football League in 1920 and won promotion to Division

Two in 1925. As Charles joined them, they were in the throes of a battle

against relegation which was ultimately unsuccessful and they ended

the season by dropping back into the Southern Section of the old Third

Division.

Nevertheless Swansea was a real hot bed of football at the time, giving

the national team such great servants as Roy Paul, Trevor Ford, Cliff

Jones, Ivor and Len Allchurch and Jack Kelsey.

Charles recalls those early days: 'Nearly all the clubs take on as many

promising youngsters as they can and put them to work on the ground. It

is impossible for them to sign as professionals until they are seventeen,

so these youngsters spend their time doing any odd job around the ground.

They weed the pitch, sweep the terraces, help to keep the dressing rooms

clean and tidy, help to look after the boots of the senior players, and

generally make themselves useful. It is hard work, but for a lad desperately

interested in the game, it is enjoyable work ... the really keen boy can

pick up a host of tips simply by keeping his eyes and ears open, and even

the back breaking job of weeding becomes pleasant if you dream of the

future - of playing for Swansea Town and Wales. I was disappointed I never

got a chance, but you just had your hope to keep you going.'

Charles spent a couple of years at Vetch Field without ever getting the

sniff of a game, but there were interested eyes being cast around the

place.

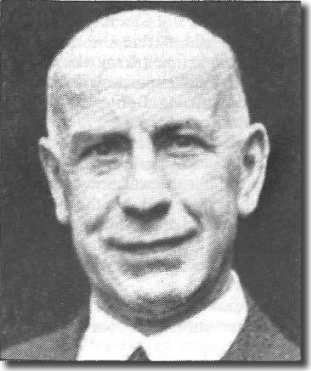

Like Swansea, Leeds had been relegated after the war and the charismatic

Major Frank Buckley, who had built

Wolves from a struggling team into a crack First Division outfit, had

been brought in to revive their fortunes in the summer of 1948. Buckley

had always valued scouting and youth programmes and had quickly instituted

both at Elland Road. Jack Pickard was Buckley's chief scout in South Wales

and he spent much of his time at Swansea.

Charles again: 'We used to train with the senior players on a Thursday

and this fella called Jack Pickard from Leeds United would watch us. He

saw something he liked and sent three of us - me, Bobby Hennings and Harry

Griffiths - up to Leeds. He came to see my mother and father in our village

just outside Swansea. My father was a steel fixer and my mother worked

too. He told them what he wanted and my mother said, "John can't

go to Leeds." Mr Pickard's face dropped and he asked why not. My

mother said, "He hasn't got a passport!" But I went. And I'm

glad I did.'

Charles accepted the invitation to go to Elland Road for a trial. Buckley

saw enough of Charles in the first few weeks to make his mind up and quickly

persuaded him to sign for the club. He offered a £10 signing on fee, a

wage of £6 a week, and a new suit and overcoat as a bonus. It was the

start of a wonderful relationship which saw  Buckley

mould Charles into one of the finest talents of his generation.

Buckley

mould Charles into one of the finest talents of his generation.

back to top

Buckley was an eccentric character and strong willed. He had an innovative

approach to the game and tried out all sorts of unconventional methods,

including the legendary monkey gland treatment. One of his other hobbyhorses

was versatility and he insisted on players being two footed and able to

operate in a number of different roles in order to develop their all round

game.

In those days, Charles was notionally a left-half, but Buckley insisted

on trying him out at right back, although he had moved again, to centre-half,

by the time he made his debut, and later got switched with glorious effect

to the Number 9 shirt.

There are different schools of thought about Buckley's methods. Some

dismissed him as an attention seeking fool, while others saw him as visionary,

anticipating many of the modern footballing developments, such as the

Total Football mastered by the marvellous Netherlands and West Germany

sides of the 1970's. He was certainly successful and Charles is clear

he was 'a great man. He was desperate to win. If we were losing at half

time, he would run through the entire team and say what we were doing

wrong. He had a quick tongue too. One day he said to our centre-forward,

"Frostie - Jesus Christ was a clever man, but if he'd played football

he'd never have found you." He was like that. He had a sense of humour,

but he was a very, very hard man.'

Charles was nervous when he started at Leeds but says: 'I must have done

well because the Major told me he was satisfied and that he would like

me to join the Leeds United groundstaff. He promised to find me good digs

and to give me all the coaching I required. He kept both promises.

'He didn't do much coaching on the training field. Instead he would call

me into his office after a match and say: "Jack" - he always

called me Jack, not John - "you shouldn't have done so and so."

But he'd also tell me what I'd done right and suggest one or two things

I might like to try. I would think about what he said and try to do it

in matches.'

The next few months saw Charles' life change dramatically - the skinny

youngster was filling out and after a dozen or so games at right back,

the Major switched him to centre-half for a Yorkshire League match against

Barnsley. 'By this time I had grown and learned a lot. I was over six

feet tall and I tipped the scales at thirteen stone - quite a change from

the stripling of a boy they knew at Swansea. I could use both feet equally

well, and I had learned much about the art of tackling and positional

play. That game against Barnsley was the turning point in my career. Not

only did I play well enough to please all who saw the match, but I discovered

that I enjoyed playing at centre-half more than wing-half or full-back.

Centre-half, I felt, was my natural position.'

Richard Coomber from his book King John: 'Leeds United

arranged to play a friendly against Queen of the South on Easter Tuesday,

19 April 1949. The Doonhammers were in the Scottish top flight in those

days, but, more importantly from the crowd's point of view, they included

centre forward Billy Houliston who was fresh from Scotland's 3-1 triumph

at Wembley where he had tormented England's finest, Neil Franklin.

'Leeds' veteran first choice centre half, Tom Holley, had an ankle injury,

so Frank Buckley decided that this was the ideal opportunity to blood

the promising Welsh teenager. Dick Ulyatt, of the Yorkshire Post, had

been watching the youngster emerge and was delighted to report the next

day: "I saw another most promising centre-half, Leeds United's 17-year-old

John Charles, play his first senior match - an inter-club fixture against

the Dumfries team, Queen of the South, which was drawn 0-0.  Lacking

the bite of a league fixture, the pace was not so fast as usual for many

of the players. Charles was not one of these, for his opponent was William

Houliston, whose refreshing vigour is welcomed by everyone except goalkeepers

and centre half backs. Young Charles came through the ordeal no worse

than the England players at Wembley a week ago, and from his cool assurance,

his tactical skill and sturdy build, it seemed evident that United's manager,

Major Buckley, had found a player of great promise."

Lacking

the bite of a league fixture, the pace was not so fast as usual for many

of the players. Charles was not one of these, for his opponent was William

Houliston, whose refreshing vigour is welcomed by everyone except goalkeepers

and centre half backs. Young Charles came through the ordeal no worse

than the England players at Wembley a week ago, and from his cool assurance,

his tactical skill and sturdy build, it seemed evident that United's manager,

Major Buckley, had found a player of great promise."

'According to Holley, Houliston told him afterwards that Charles was

"the best centre-half I have ever met" and Major Buckley was

clearly delighted because he picked John to make his league debut at Blackburn

Rovers the following Saturday.'

Leeds were in the bottom half of the Second Division, but were safe enough

and Buckley decided to blood the youngster, at centre-half, on April 23,

1949. Ulyatt reported thus in the Yorkshire Post: 'The game was

17-year-old Charles' Football League debut. He held Blackburn's reserve

centre-forward, Fenton, and Fenton's second half deputy, Priday, showing

accuracy of kick, tackle and heading. There could be nothing but satisfaction

for United in the boy's form.'

Charles did well enough in a goalless draw at Ewood Park to keep his

place for the final two games of the season, another 0-0 draw, at home

to Cardiff City, and then for a trip to the far off city of London, which

saw Leeds lose 2-0 to QPR.

back to top

Charles had made a good start to his career and was in the side to stay.

Injuries apart, he was never out of the Leeds side again while he was

at the club. He was an ever present in the team that did exceedingly well

the next season, 1949/50. They finished

in an impressive fifth spot and beat Spurs 3-0 to end the powerful London

club's 22 match unbeaten run. The biggest game of the season was against

Tottenham's fierce London rivals, Arsenal. For once, Leeds had a decent

Cup run and made it all the way through to a Sixth Round tie at Highbury.

Leeds lost 1-0 in an enthralling match and Charles was the lynch pin of

an outstanding performance which had pushed the eventual Cup winners to

the limit.

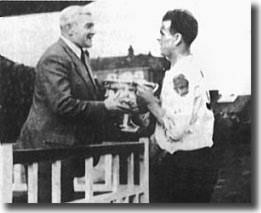

Charles gained a personal reward for his form that season when he was

called up for the Welsh team and became the youngest player to appear

for his country when he turned out in a 0-0 draw against Ireland. It was

a depressing day, however.

Beforehand, he had been touted as the Golden Boy of Welsh football, yet

had a curiously lacklustre game and only played once more in the next three seasons. The Yorkshire Post

made no bones about it: 'Charles was a complete failure ... he was prepared

neither to go in and tackle nor stand off and wait ... he was lost in

helpless indecision.' It was a rare setback in a meteoric career and Buckley

wisely built up his young star, convincing him he would get another chance.

only played once more in the next three seasons. The Yorkshire Post

made no bones about it: 'Charles was a complete failure ... he was prepared

neither to go in and tackle nor stand off and wait ... he was lost in

helpless indecision.' It was a rare setback in a meteoric career and Buckley

wisely built up his young star, convincing him he would get another chance.

He did return to the side, but it took a year. He played against Switzerland

in one of a number of games organised to celebrate the Festival of Britain.

Wales went into a 3-0 lead and things were going well. However, the tide

turned thereafter and Charles got another rude awakening during what he

later described as 'the worst 20 minutes of my life'. The Swiss centre-orward

and skipper, Bickel, started to roam around the pitch, causing the youngster

problems he'd not encountered before, and with ten minutes left the score

was 3-2. 'From that moment we had to hang on grimly, and we did,' he recalled

grimly. It was a couple of years before the Welsh selectors gambled on

Charles again.

His international disappointment didn't harm Charles' club form, however,

and 1950/51 saw Leeds have another

successful season, although with less glory. They finished fifth again,

although they never looked to be promotion contenders. The end of the

season, however, was to mark a turning point in a fledgling career.

There was an injury crisis as Leeds came to play Manchester City over

Easter and the Major's solution was a shock for Charles: 'He told me,

"There are two centre-forwards injured - you'll have to play there

- I haven't got anyone else to put in." I went in the side and we

got beaten 4-1. When he told me I'd have to play there again at home to

Hull City on Easter Monday, I said, "You saw me, I didn't get a kick."

Anyway I did play and I got two goals. Next day, the Major said, "Well

done, lad, you'll stay at centre-forward." I don't know how I did

it. Things just went right for me.'

Dick Ulyatt recorded the Hull game for the Yorkshire Post: 'Interest

was divided at Elland Road yesterday between the form of John Charles,

Welsh international centre-half now playing as Leeds United's centre-forward,

Neil Franklin's clash with him, and the referee's determination to finish

the match despite a heavy ground which eventually became covered in snow.

'Charles scored twice and thereby justified United's experiment. Franklin

played delightful football, and but for him United might have won by six

or seven goals, and the referee beat the snow.

'Franklin confirmed previous impressions that he is rapidly settling

down. He had to cover all parts of his half of the field and he did it

well. He was not once at fault when Charles scored or again when the young

Welshman

had a shot blocked on the line by Hassall. Charles got his goals by moving

about the field; here was no orthodox down the middle centre forward but

a man with a football brain, able to sense the right position to take

up.

Welshman

had a shot blocked on the line by Hassall. Charles got his goals by moving

about the field; here was no orthodox down the middle centre forward but

a man with a football brain, able to sense the right position to take

up.

'Charles is not yet as good a centre-forward as he is a centre-half-back;

all his footballing life he has had the ball coming to him, now it is

rolling with him and needs a different technique, but when he has mastered

that he may be very good indeed. Both his goals were well taken.'

Neil Franklin was an England defender and the Hull side contained international

inside-forwards Raich Carter and Don Revie, both of whom later managed

Charles at Elland Road.

From 1950 until 1952 Charles was away on National Service with the 12th

Royal Lancers at Carlisle. The Army allowed him to turn out for Leeds

but also saw to it that he played for them, and in 1952 Charles skippered

his side to the Army Cup. It was during this period that he had operations

to repair cartilages in both knees.

Surgery meant Charles missed a large chunk of the 1951/52

season. When he returned in December, and for most of the next season

and a half, Buckley decided he needed him more at the back. Charles pulled

on the No 9 shirt for only the last three games of the season, without

scoring. The manager, however, was convinced that the Welshman could make

a go of it and was to finally see his faith reap its reward in 1952/53.

An appreciation - Part

2 King Charles - Part 3 Red Dragon - Part

4 The Italian Job - Part 5 End of an Era

back to top

An

appreciation - Part 2 King Charles -

Part 3 Red Dragon - Part

4 The Italian Job - Part 5 End of an Era

An

appreciation - Part 2 King Charles -

Part 3 Red Dragon - Part

4 The Italian Job - Part 5 End of an Era Buckley

mould Charles into one of the finest talents of his generation.

Buckley

mould Charles into one of the finest talents of his generation. Lacking

the bite of a league fixture, the pace was not so fast as usual for many

of the players. Charles was not one of these, for his opponent was William

Houliston, whose refreshing vigour is welcomed by everyone except goalkeepers

and centre half backs. Young Charles came through the ordeal no worse

than the England players at Wembley a week ago, and from his cool assurance,

his tactical skill and sturdy build, it seemed evident that United's manager,

Major Buckley, had found a player of great promise."

Lacking

the bite of a league fixture, the pace was not so fast as usual for many

of the players. Charles was not one of these, for his opponent was William

Houliston, whose refreshing vigour is welcomed by everyone except goalkeepers

and centre half backs. Young Charles came through the ordeal no worse

than the England players at Wembley a week ago, and from his cool assurance,

his tactical skill and sturdy build, it seemed evident that United's manager,

Major Buckley, had found a player of great promise." only played once more in the next three seasons. The Yorkshire Post

made no bones about it: 'Charles was a complete failure ... he was prepared

neither to go in and tackle nor stand off and wait ... he was lost in

helpless indecision.' It was a rare setback in a meteoric career and Buckley

wisely built up his young star, convincing him he would get another chance.

only played once more in the next three seasons. The Yorkshire Post

made no bones about it: 'Charles was a complete failure ... he was prepared

neither to go in and tackle nor stand off and wait ... he was lost in

helpless indecision.' It was a rare setback in a meteoric career and Buckley

wisely built up his young star, convincing him he would get another chance. Welshman

had a shot blocked on the line by Hassall. Charles got his goals by moving

about the field; here was no orthodox down the middle centre forward but

a man with a football brain, able to sense the right position to take

up.

Welshman

had a shot blocked on the line by Hassall. Charles got his goals by moving

about the field; here was no orthodox down the middle centre forward but

a man with a football brain, able to sense the right position to take

up.