An appreciation - Part

1 Welsh gold - Part 2 King Charles -

Part 3 Red Dragon - Part

5 End of an Era

An appreciation - Part

1 Welsh gold - Part 2 King Charles -

Part 3 Red Dragon - Part

5 End of an Era

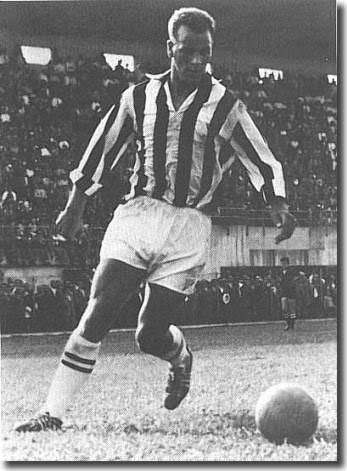

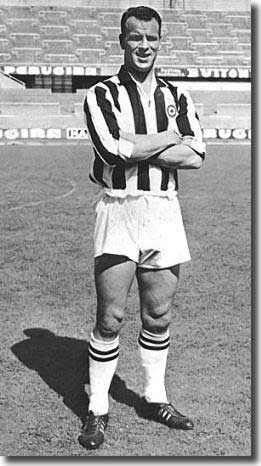

John Charles was one of the outstanding footballers of the 1950's and

his prodigious talents were coveted throughout Europe. It was astonishing,

then, that he remained with Leeds United, a modest Second Division club

from Yorkshire until he was 25 and did not make his debut in the top flight

until 1956, when he spearheaded the club's promotion success.

He took Division One by storm and finished the country's top scorer

with 38 goals, only just failing to break the club record of 42 he had

set three years previously. There had been rumours and newspaper talk

for years of other clubs making a move for the Welshmen, but always

the Leeds United directors had resisted all offers.

Now, though, in the spring of 1957, things had changed. The club's

Elland Road ground had been ravaged by fire the previous September and

the main stand razed to the ground. It had not been adequately insured

and the difference between the pay out which the club received and the

cost of the new stand was around £60,000. Leeds United were in dire

need of money, the sort of money a world class player like John Charles

could fetch.

There were noises from the continent of possible bids and eventually

the directors of the club announced on 10 April that they would not sell

Charles to another British club, but would be prepared to listen to bids

from foreign clubs. Charles takes up the story: 'I was called into the

manager's office and he said "Madrid are looking at you." I

said "Madrid who?" He looked at me and said, "Real Madrid"

and, of course, I'd heard of them. I'd seen them on television and they

were one of the best teams in the world. But I didn't want to go. I was

young and didn't have much experience of going abroad. Soon afterwards,

he called me back in and told me Madrid weren't interested any more. I

thought, fine. Then he said, "Lazio are after you." I said,

"Where's Lazio?" He looked at me and said "It's in Rome."

I asked him if he wanted to let me go and he said he'd have to if the

money was right. So I said alright. But then two days later he called

me into his office and said "Juventus want you." I said, "Who

are Juventus?" and he looked at me once more and said, "They're

one of the best teams in Italy." I'd never heard of them, but it

was different then. You didn't have the television and press coverage

you get now.'

back to top

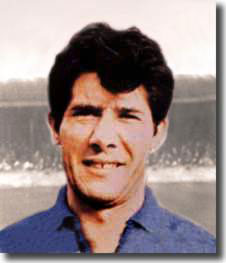

Charles also recalls conversations with Gigi Peronace, an Italian agent,

who was searching for new talent: 'He came round my house and said he'd

like me to go and play in Italy. He was a smashing feller who spoke very

good English. He was nothing like the scouts who huddled on the touchlines

in England. Gigi was a Lazio fan and wanted me to go there but a month

later he came back and said he was now working for Juventus and I should

join them.'

Richard Coomber recorded happenings thus in his book King John:

'The transfer was thrashed out in room 233 of the Queens Hotel in Leeds.

Charles remembers: "I walked to the hotel to meet the Italians and

saw the Leeds directors Mr Bolton and Mr Westwood who were wearing black

coats and black caps. Mr Bolton came up to me and said 'It's  so

sad that we're losing you, John', but as soon as they got the cheque they

shot off to put it in the bank! When Umberto suggested we should have

a drink to celebrate the deal, they were nowhere to be found."

so

sad that we're losing you, John', but as soon as they got the cheque they

shot off to put it in the bank! When Umberto suggested we should have

a drink to celebrate the deal, they were nowhere to be found."

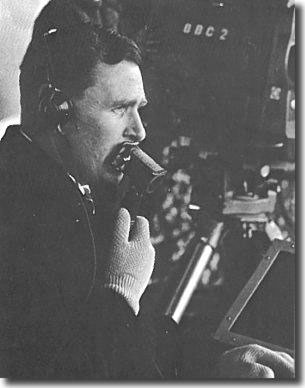

'The negotiations between the clubs were fairly straightforward. Juventus

haggled for a while but even at £65,000 they thought they had a good deal.

Much tougher were the talks over personal terms held just along the corridor

in room 222. For the first time a British player had employed the services

of an agent to do the deal, and Teddy Sommerfield, used to negotiating

with the BBC on behalf of people like Eamonn Andrews and Kenneth Wolstenholme,

was well prepared and ready to strike a hard bargain. With Wolstenholme

there to help him on football matters, Sommerfield went through the contract

item by item.

'Downstairs the press were wondering what was going on - a player's contract

usually took only ten minutes once the clubs had agreed. Twice refreshments

were summoned to the room, brought by an awestruck Italian waiter, who,

once in, was reluctant to leave the scene of such important goings on.

'Finally, agreement in principle was reached just after midnight but

there was still plenty that could go wrong. Charles flew to Italy to approve

the arrangements made for him and his family's accommodation in Turin.

Then there was the matter of a medical, especially on those knees, both

of which had undergone cartilage operations. It was the most thorough

examination Charles had experienced but the doctor, Professor Amilcare

Basatti, declared: "Charles is the fittest man I know playing football,

I have never seen a better human machine in a lifetime in medicine."

'The biggest stumbling block was completely in Juventus' hands. They

were facing the spectre of relegation and if that happened they would

not be allowed to sign their new overseas star striker. Fortunately they

just clung on to their senior status and the deal was done. Charles received

£10,000 signing on fee over the two year period of his first contract,

a modest weekly salary but rich rewards in bonuses as well as a luxurious

way of life. The Association Football Correspondent of The Times

recognised the importance of Charles' transfer. He wrote: "The implications

of the move by Charles are as yet hidden. But after the departure of Firmani,

an Italian by antecedent, from Charlton Athletic to Italy last year, it

may one day prove a lever to greater incentives and rewards for the footballer

at home."

'Four years later, after a massive campaign by the players union and

a stand by George Eastham, the retain and transfer system was changed

and the maximum wage in England was removed.'

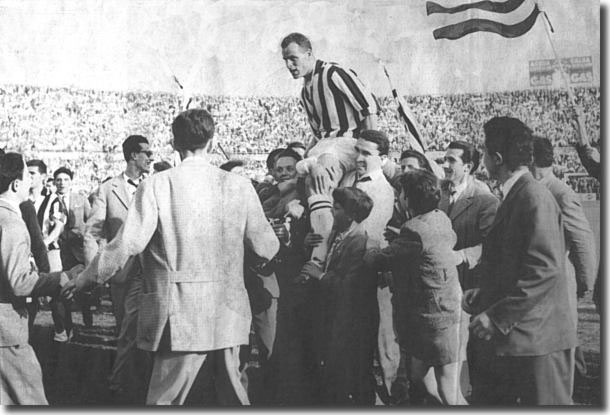

The Welshman's final game before his move to Italy was, fittingly enough,

at Elland Road, with Don Revie's Sunderland side as the visitors and Geoffrey

Winter wrote the following piece in the Yorkshire Post: 'John Charles

left Leeds United's ground for the last time yesterday  in

a blaze of glory and trailing 100 small boys pleading for his autograph.

So ended a chapter in football history, which will be told and retold

as long as men wear Leeds United favour.

in

a blaze of glory and trailing 100 small boys pleading for his autograph.

So ended a chapter in football history, which will be told and retold

as long as men wear Leeds United favour.

'The black eyes of Signor Gigi Peronace, the Juventus scout, who was

there to take delivery of John Charles when the match was over, glistened

with excitement and satisfaction whenever the great man got possession

of the ball. "That's my boy," they seemed to say...

'There was a disturbing incident in the Sunderland goalmouth in which

Charles, running at his impressive top speed, collided with a player and

hurtled to the ground at the back of the net. The goalkeeper was prone

too. Trainers raced to give first aid and someone shouted: "He's

broken a leg." No one imagined for one moment that he might be referring

to the goalkeeper. Signor Peronace looked particularly anxious and was

no doubt pale under his Mediterranean tan. Fortunately no serious harm

was done to either player.'

A few British players had made the trip to the strange lands of Italy

prior to Charles, but it was undoubtedly he who paved the way for a mass

exodus with an astonishing stay in the country. By the time he returned

to Britain five years later, Charles had made himself a folk idol in Turin,

a bona fide legend, one of the most feted of Juventus' many stars.

Almost single handedly he inspired a magnificent era for the club and

became revered on the continent as a truly world class performer, almost

single handedly turning relegation candidates into world beaters.

It wasn't all plain sailing, however, and there were many new things

that the Charles family had to get used to.

Charles: 'As a family, we weren't what you would call sophisticated back

then. Had I heard of Turin? I doubt if I'd heard of Italy when Juventus

came in for me. It was a complete culture shock because in Leeds I'd been

a bitter-shandy man, suddenly I was presented with red wine at the pre-match

lunch. The first time I was faced with a bowl of spaghetti it went everywhere

but down my bloody throat.'

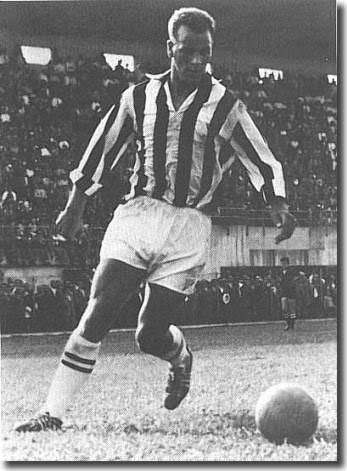

Charles may have been a messy eater in those early days, but in the No

9 shirt he was both a physical colossus and a gentleman; even the fans

of Juventus' bitter city rivals Torino worshipped him.

'I didn't set out to win them over but in my first Turin derby I beat

the centre-half but accidentally struck him with my elbow and knocked

him clean out. I only had the goalie to beat but it didn't seem fair so

I kicked the ball out for a shy so the fella could have treatment.'

back to top

In the modern era of diving, feigning injury and assorted chicanery,

such action would be inconceivable but to Charles it was a question of

honour. 'I can't be doing with a lot of the shenanigans you see out on

the pitch these days.' Didn't you ever, ever, cheat a referee or an opponent?

An emphatic 'No' came the reply.

'Anyway, from that moment on, the Torino supporters always treated me

with great respect. I remember one Sunday afternoon they beat us 3-2 and

I missed a penalty - maybe that's why I was so popular - and I was woken

up about three in the morning by this incredible din of car horns. When

I went out on the balcony there was a traffic jam of Torino fans hanging

out of the windows waving their red flags.'

Typically, Charles invited them in, whereupon they proceeded to drink

his valuable wine cellar dry while trying to persuade him to quit Juventus

and join Torino.

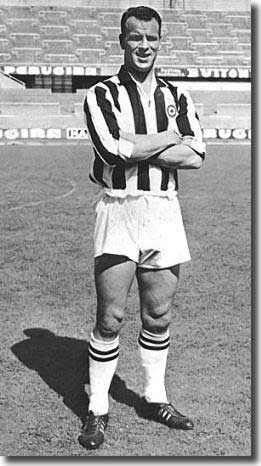

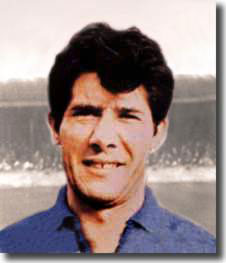

The Juventus side was littered with great players like Giampiero Boniperti

and Argentinian Omar Sivori ('whenever he scored we all used to run away

in the other direction because he was such an ugly bugger no one wanted

to

kiss him'), but it was Il Buon Gigante the supporters embraced to their

collective bosom.

to

kiss him'), but it was Il Buon Gigante the supporters embraced to their

collective bosom.

'Why? Because I scored a few goals, probably,' he reasoned modestly.

A few goals being a total of 93 in 155 Serie A games in his five seasons

in Turin during which Juventus won three league titles and two Italian

Cup finals; a few goals like the flying header against AC Milan in the

San Siro which was still being used in the introduction to Italy's Sunday

night football highlights TV programme in 1978 - 20 years after the deed;

a few goals like the audacious winner he scored in the 1959 cup final

victory against Fiorentina when he cushioned a cross on his forehead then,

as the goalkeeper came out, cheekily nodded the ball over his head like

a sealion toying with a beachball in the circus ring.

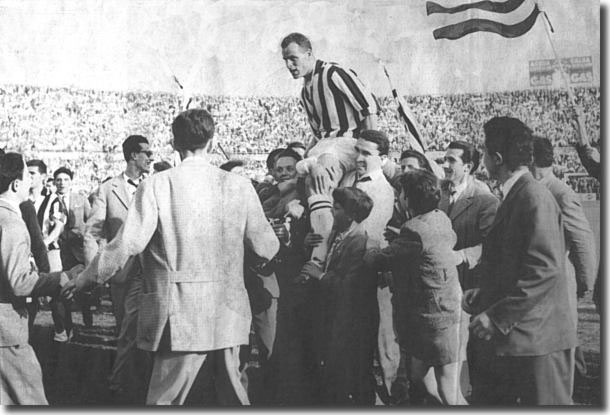

Little wonder when John and Glenda Charles were invited to the Stadio

delle Alpi for Juventus' final game of the season in May 2001, he stood

in the middle of the pitch to a standing ovation as the acclamation for

Gio-vaaa-ni . . . Gio-vaaa-ni . . . Gio-vaaani . . . rained down upon

him from the sweeping grandstands. 'The tears were rolling down my cheeks,'

whispered Glenda. 'They presented us with the most beautiful photograph

album of the occasion and a video.'

'To be honest, I loved the admiration. If you're lucky enough to be born

with a gift as so many people kindly say I was, then you might as well

enjoy it,' Charles added. 'It's lovely to be so well remembered in Italy

after all this time; maybe it's because Italian families tend to be so

close-knit that they still show me such affection.'

Rick Broadbent, in Looking For Eric, told the story of Charles'

stay in Italy this way:

'Italy would be a culture shock for Charles and Peggy. Turin was a different

world and the football was unrecognisable from that which Charles had

been used to in Yorkshire. "Life for a forward in Italy was hell,'

he recalls. 'It was very defensive football over there. If you scored

it was a miracle. The popular formation was 1-8-2 and out and out attackers

were luxuries nobody could afford."

'It was because of this dour philosophy that most British journalists

predicted Charles would flop in Italy. They also questioned whether his

reputation as an unflappable gentleman would survive the strict referees

and the theatrical antics of the players. Charles admits it was difficult.

Most referees were homers and there was always an undercurrent of corruption,

as shown when one Italian club president bought all the league referees

lavish Christmas presents. The players, too, had some dubious habits.

Though they were less physical - "powder puff tackling" as Charles

calls it - and shocked by what they considered the barbarism of the English

game, they were already honing their diving and shirt pulling tactics.

Charles believes both styles have their merits. "Don't, for goodness'

sake, make it a game for cissies, but don't let it become a dangerous

game either." In 1962 he summed up his feelings by saying: "The

continentals will have to accept that soccer is a man's game, but the

British have to accept that soccer is an art."

'It is not difficult to see why Charles was such a success in Italy.

He threw himself into Italian society, bought a stake in a restaurant

in the centre of Turin, learned the language and always respected the

fact he was the foreigner. "The supporters were fanatical,"

he says. "I picked up the lingo, which you have to if you are living

in a foreign country because it means you can go out and enjoy the new

life you've got. The people there were fantastic to me. The Italians are

lovely  people,

very warm, very much like the Welsh. 'I admit I didn't know where Turin

was, originally, but I was determined to make it work. To start off with,

I was lucky because I met a player who could speak English better than

I could Italian. I got homesick, but I was determined to stick it out

and I enjoyed it. It was a terrific era. Omar Sivori, a little Argentinian

fella who was European Footballer of the Year in 1961, came at the same

time as me and we mixed well. Then we had a big inside right called Giampiero

Boniperti as our captain and he was a fantastic player."

people,

very warm, very much like the Welsh. 'I admit I didn't know where Turin

was, originally, but I was determined to make it work. To start off with,

I was lucky because I met a player who could speak English better than

I could Italian. I got homesick, but I was determined to stick it out

and I enjoyed it. It was a terrific era. Omar Sivori, a little Argentinian

fella who was European Footballer of the Year in 1961, came at the same

time as me and we mixed well. Then we had a big inside right called Giampiero

Boniperti as our captain and he was a fantastic player."

'Charles and Sivori would score 250 goals between them for Juventus,

but the "ugly little bugger", as Charles refers to his former

strike partner, did present some problems. On one occasion Sivori was

threatened with a Mafia bullet if he scored in the next game. In the bumbling

manner of a Latino Mr Bean, Sivori did score when a ball ricocheted off

the back of his head into the goal. Fearing a sniper's bullet, Charles

and his team-mates formed a protective cortege around the little Argentinian

and shuffled into the tunnel. Sivori flew back to Turin immediately. Meanwhile,

the game went on and Charles scored the winner, only for the referee to

disallow the strike. When Charles asked why the goal had been ruled out,

the referee said: "Like Mr Sivori, I want to get home safely."

'Such nuances of Italian sporting life were still to be discovered by

Charles as he attended his first training session with his new club. He

also made the mistake of buying a Citroen car, which was not the wisest

of moves considering the Agnelli family owned the Fiat empire and provided

free cars for every Juventus player.

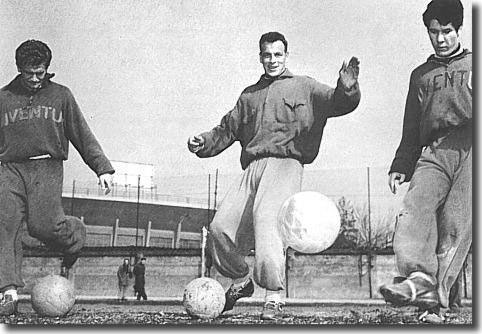

'Despite such faux pas, it took Charles just three weeks to conquer Italy.

His debut came on 8 September 1957 against Hellas Verona. Goals from Boniperti

and Sivori had made the score 2-2 when up popped Charles to score the

winner. The following week he scored the only goal in the victory over

Udinese and he then hit the decisive strike in a 3-2 victory over Genoa.

He had been the matchwinner in his first three games. Small wonder the

likes of Vittorio Fioravanti were won over.

back to top

'"It went from there and in the first year I was there we won the

championship. We were promoted from the Second Division with Leeds, but

that was as far as it went. In Italy we won three championships and two

cups." In the stifling world of limpet-like defenders and the conservative

style the Italians called catenaccio, Charles had also defied all the

doubters by scoring an incredible 28 goals in 34 games, including a trio

of hat tricks, against Atalanta, Sampdoria and Lazio. It was enough for

him to be voted Italian Footballer of the Year.

'At the time Britain's highest paid player was Fulham's Johnny Haynes

who was making £5,000 a year. That figure had caused the same sort of

shockwaves as Roy Keane's demands would some 40 years later, but Charles

suggested there would be a national strike if Italians were forced to

play for such a pittance. In his final season in Turin, Charles' basic

salary was £7,000 a year, but he made a small fortune from bonuses. "Sometimes

the supporters would get together  after

a game and themselves pay a bigger bonus to the players," he recalls.

"On one occasion the Roma players were offered £300 each to beat

Juventus. It varied all the time. Say the chairman had won a bet with

the chairman of Inter Milan, it was not uncommon in those circumstances

for each player to get a £500 bonus." Unlike Britain, there was no

maximum wage in Italy and individual salaries varied. There were also

lucrative signing-on fees. "When I first went to Italy I was getting

£18 a week, which was less than I was getting at Leeds; but I got a £2,000

signing on fee and a luxury apartment. I was lucky. Some of the other

clubs were struggling to pay their players, and there were stories going

around that people were having to wait two months to get their wages."

after

a game and themselves pay a bigger bonus to the players," he recalls.

"On one occasion the Roma players were offered £300 each to beat

Juventus. It varied all the time. Say the chairman had won a bet with

the chairman of Inter Milan, it was not uncommon in those circumstances

for each player to get a £500 bonus." Unlike Britain, there was no

maximum wage in Italy and individual salaries varied. There were also

lucrative signing-on fees. "When I first went to Italy I was getting

£18 a week, which was less than I was getting at Leeds; but I got a £2,000

signing on fee and a luxury apartment. I was lucky. Some of the other

clubs were struggling to pay their players, and there were stories going

around that people were having to wait two months to get their wages."

'There were plenty of other differences between Leeds and Turin and

England and Italy. Whereas most British clubs were limited companies,

Italian clubs were run by wealthy directors, who gained their position

through money rather than votes. Charles believed that, despite the undemocratic

approach, they were more effective. At the time he said: "Don't think

for a moment that I am subscribing to the popular image of an English

director - a half stupid slave driver whose ever increasing avoirdupois

is covered by an antiquated gold watch chain and whose knowledge of football,

if it ever existed, deserted him years ago; but there are directors who

try to run the whole show themselves and haven't the qualification to

do so."

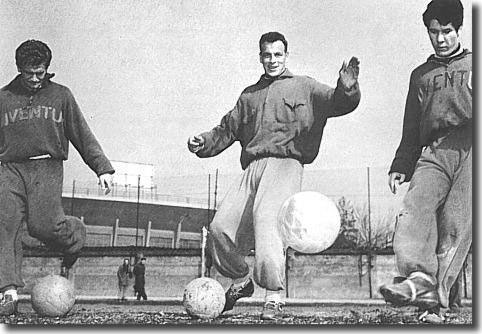

'Training was also different. Fitness was viewed to be of paramount importance

in Britain, but ball skills were valued more highly in Italy. The theory

in Britain was that if you starved a player of a ball during the week,

he would be chomping at the bit come Saturday afternoon. Again Charles

sided with his new country. "I have often found the British system

makes a player, even if he is hungry for the ball, completely incapable

of using it when he gets it."

'Social rules were another eye opener for Charles. "Young people

are not allowed the same freedom as our young people are," he wrote

in 1962. "If any young lovers are found necking in public, in the

parks or cinema, they are hauled off by the police and fined. The girl

can then get a reputation as being a loose young hussy."

'For those of us who believe Italians to be a bunch of oversexed Lotharios,

wearing leather jackets and Latin scowls as they drive around on their

Lambrettas nicking old ladies' handbags, such a picture of moral rectitude

sounds unlikely. But it was there, in Article Seven of the Football Clubs'

Regulations, stating that the player should always "conduct himself

in a correct manner everywhere and live a decent moral and physical life".

Charles adds: "They bought you lock, stock and barrel. The rewards

were high, but you had to behave well. It was an education living over

there." Presumably, those rules had been waived by the time Paul

Gascoigne arrived in the early 1990's.'

On the official Juventus website there is a page headed 'John Charles:

Juve's finest ever forward'. It reads: 'Devastating is the adjective that

springs to mind  when

you recall the power of Welsh international John Charles. Charles was

the greatest - and not only in terms of stature - centre forward in Juventus

history. World class strikers have come and gone. Deserving of special

mention here are "Farfallino" Borel, John Hansen, "Bobby-go!"

Bettega, Jose Altafini, Petruzzu Anastasi and Paulo Rossi. They were all

great in their own right but there was no one quite like Charles.

when

you recall the power of Welsh international John Charles. Charles was

the greatest - and not only in terms of stature - centre forward in Juventus

history. World class strikers have come and gone. Deserving of special

mention here are "Farfallino" Borel, John Hansen, "Bobby-go!"

Bettega, Jose Altafini, Petruzzu Anastasi and Paulo Rossi. They were all

great in their own right but there was no one quite like Charles.

'For anyone who saw Charles play in the late 1950's and early 1960's

when he was at his peak, the Welshman was the stuff of legends. There

is a famous photo of him scoring yet another header and the goalkeeper

is clinging on to him while two defenders try in vain to stop him. Another

picture shows the dreadnought striker leaping above Vieri in a derby match

and even at full stretch, the Torino keeper is nowhere near him.

'John Charles was more than the proverbial battering ram. He was blessed

with the ability to hang in the air and, as if suspended in motion, he

would use his momentary advantage to decide whether to head for goal or

lay the ball off for a colleague to apply the coup de grace. His unselfish

play won him many admirers.'

Such fond affection was fully justified by the contribution that Charles

made to the history of Juve. In the five years he spent in Turin, Juventus

won three championships and two Italian Cups. Charles was Italian Footballer

of the Year and played for the Italian League. In 1958 and 1959 he was

in the top three in the polls for European Footballer of the Year. He

scored an unheard of 108 goals in 155 games for the club.

In 1960 he scored 23 goals in 34 games as Juventus clinched the League

and Cup double. The following season he scored 15 goals in 32 appearances

as the title was successfully defended. So why leave?

'My wife wanted to come back and I bowed to her wishes,' he says. At

the time Charles elaborated more freely on his reasons. He cited his sons'

education, the fact his wife was from Leeds, and their shared homesickness

as the causes for his request to leave Turin.

After four years of unqualified glory, Charles decided the time was coming

when he would want to return home so, despite tremendous pressure from

Juventus, he signed only a one year extension to his contract and announced

that he would return to the Football League.

The news that Charles was open to offers from England filtered back to

Elland Road. The club had fallen back into the Second Division and were

now managed by former player Don Revie, a friend and many times rival

on the field of Charles. The Leeds United Board sensed the pressure from

their supporters and resolved to arrange a homecoming.

An appreciation - Part

1 Welsh gold - Part 2 King Charles - Part

3 Red Dragon - Part 5 End of an Era

back to top

An appreciation - Part

1 Welsh gold - Part 2 King Charles -

Part 3 Red Dragon - Part

5 End of an Era

An appreciation - Part

1 Welsh gold - Part 2 King Charles -

Part 3 Red Dragon - Part

5 End of an Era so

sad that we're losing you, John', but as soon as they got the cheque they

shot off to put it in the bank! When Umberto suggested we should have

a drink to celebrate the deal, they were nowhere to be found."

so

sad that we're losing you, John', but as soon as they got the cheque they

shot off to put it in the bank! When Umberto suggested we should have

a drink to celebrate the deal, they were nowhere to be found." in

a blaze of glory and trailing 100 small boys pleading for his autograph.

So ended a chapter in football history, which will be told and retold

as long as men wear Leeds United favour.

in

a blaze of glory and trailing 100 small boys pleading for his autograph.

So ended a chapter in football history, which will be told and retold

as long as men wear Leeds United favour. to

kiss him'), but it was Il Buon Gigante the supporters embraced to their

collective bosom.

to

kiss him'), but it was Il Buon Gigante the supporters embraced to their

collective bosom. people,

very warm, very much like the Welsh. 'I admit I didn't know where Turin

was, originally, but I was determined to make it work. To start off with,

I was lucky because I met a player who could speak English better than

I could Italian. I got homesick, but I was determined to stick it out

and I enjoyed it. It was a terrific era. Omar Sivori, a little Argentinian

fella who was European Footballer of the Year in 1961, came at the same

time as me and we mixed well. Then we had a big inside right called Giampiero

Boniperti as our captain and he was a fantastic player."

people,

very warm, very much like the Welsh. 'I admit I didn't know where Turin

was, originally, but I was determined to make it work. To start off with,

I was lucky because I met a player who could speak English better than

I could Italian. I got homesick, but I was determined to stick it out

and I enjoyed it. It was a terrific era. Omar Sivori, a little Argentinian

fella who was European Footballer of the Year in 1961, came at the same

time as me and we mixed well. Then we had a big inside right called Giampiero

Boniperti as our captain and he was a fantastic player." after

a game and themselves pay a bigger bonus to the players," he recalls.

"On one occasion the Roma players were offered £300 each to beat

Juventus. It varied all the time. Say the chairman had won a bet with

the chairman of Inter Milan, it was not uncommon in those circumstances

for each player to get a £500 bonus." Unlike Britain, there was no

maximum wage in Italy and individual salaries varied. There were also

lucrative signing-on fees. "When I first went to Italy I was getting

£18 a week, which was less than I was getting at Leeds; but I got a £2,000

signing on fee and a luxury apartment. I was lucky. Some of the other

clubs were struggling to pay their players, and there were stories going

around that people were having to wait two months to get their wages."

after

a game and themselves pay a bigger bonus to the players," he recalls.

"On one occasion the Roma players were offered £300 each to beat

Juventus. It varied all the time. Say the chairman had won a bet with

the chairman of Inter Milan, it was not uncommon in those circumstances

for each player to get a £500 bonus." Unlike Britain, there was no

maximum wage in Italy and individual salaries varied. There were also

lucrative signing-on fees. "When I first went to Italy I was getting

£18 a week, which was less than I was getting at Leeds; but I got a £2,000

signing on fee and a luxury apartment. I was lucky. Some of the other

clubs were struggling to pay their players, and there were stories going

around that people were having to wait two months to get their wages." when

you recall the power of Welsh international John Charles. Charles was

the greatest - and not only in terms of stature - centre forward in Juventus

history. World class strikers have come and gone. Deserving of special

mention here are "Farfallino" Borel, John Hansen, "Bobby-go!"

Bettega, Jose Altafini, Petruzzu Anastasi and Paulo Rossi. They were all

great in their own right but there was no one quite like Charles.

when

you recall the power of Welsh international John Charles. Charles was

the greatest - and not only in terms of stature - centre forward in Juventus

history. World class strikers have come and gone. Deserving of special

mention here are "Farfallino" Borel, John Hansen, "Bobby-go!"

Bettega, Jose Altafini, Petruzzu Anastasi and Paulo Rossi. They were all

great in their own right but there was no one quite like Charles.