An appreciation - Part

1 Welsh gold - Part 2 King Charles -

Part 4 The Italian Job - Part

5 End of an Era

John

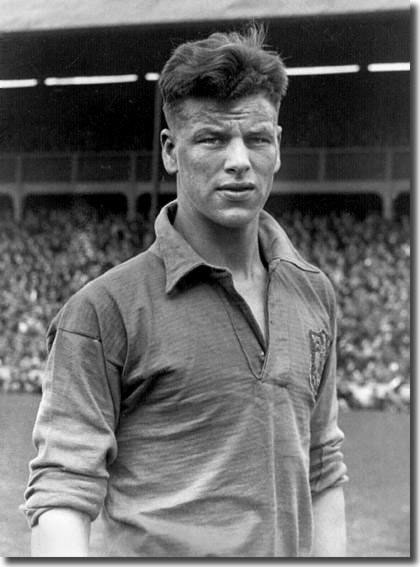

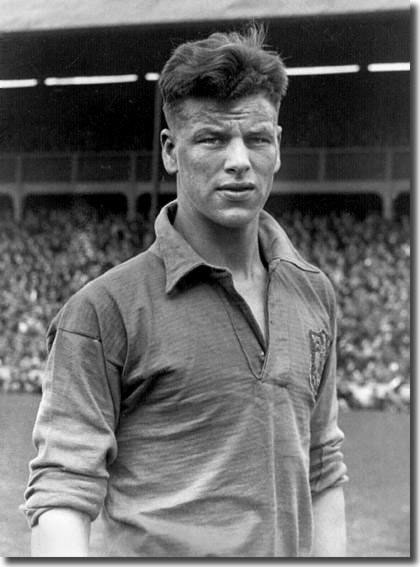

Charles broke through into the Leeds United side as a seventeen year old

in 1949 and earned rave reviews for his performance as an ever present

centre half in the team which ended 1949/50

an impressive fifth in the Second Division.

John

Charles broke through into the Leeds United side as a seventeen year old

in 1949 and earned rave reviews for his performance as an ever present

centre half in the team which ended 1949/50

an impressive fifth in the Second Division.

He gained a personal reward for his outstanding form when he was called

up for the Welsh national side towards the end of that season. At 18

years and 71 days old, he became the youngest player every to appear

for his country. It was not until the appearance of Ryan Giggs in 1992

that the record was broken. His debut came in March 1950 when he turned

out in a 0-0 draw against Ireland. It was a depressing day, however.

Beforehand, he had been touted as the Golden Boy of Welsh football,

yet had a curiously lacklustre game and only played once more in the next

three seasons. The Yorkshire Post made no bones about it: 'Charles

was a complete failure ... he was prepared neither to go in and tackle

nor stand off and wait ... he was lost in helpless indecision.'

The truth of the matter is that Charles simply fell apart under the

weight of expectation and nerves. He was playing for his country alongside

players who had been his boyhood heroes, men like Roy Paul, Trevor Ford,

Ronnie Burgess, Alf Sherwood and Wally Barnes and was in awe to be in

their company.

He said of the matter: 'It seemed like only yesterday that I was a starry

eyed youngster on the ground staff at Swansea, proud to look after the

boots of Roy Paul and Trevor Ford. Now I was playing with them in the

same Welsh international team. It was incredible. But I had reckoned without

the footballer's biggest enemy - nerves. My sturdy legs turned to jelly.

My stomach was devoured by a battalion of butterflies. My vision and judgement

were clouded by worry - worry that I would make a mistake.'

It was a rare setback in a meteoric career and the canny old Leeds

United manager, Major Frank Buckley,

wisely built up his young star, convincing him he would get another

chance.

back to top

He did return to the side, but it took a year. He played against Switzerland

in one of a number of games organised to celebrate the Festival of Britain.

Wales went into a 3-0 lead before Charles experienced what he described

as 'the worst 20 minutes of my life'. The Swiss centre-forward and skipper,

Bickel, started to roam around the pitch, causing the youngster problems

he'd not encountered before, and with ten minutes left the score was 3-2.

'From that moment we had to hang on grimly, and we did,' he recalled grimly.

It was a couple of years before the Welsh selectors gambled on Charles

again, having twice gambled and failed with the youngster.

Early in 1952/53 Leeds manager Buckley

had finally seen experiments with using Charles as a forward come very

good and after hitting a couple of goals against Halifax in the West Riding

Senior Cup Final, he became a fixture as the leader of the Leeds attack,

ending the season with 27 goals.

Such form also enabled Charles to force his way back into the international

reckoning after his disastrous first two appearances. He finally made his mark on 15 April 1953 when he played

in Belfast against Northern Ireland.

two appearances. He finally made his mark on 15 April 1953 when he played

in Belfast against Northern Ireland.

The Welsh team had just taken a frightful 5-2 thrashing from England,

but Ray Daniel at centre-half and Trevor Ford at centre-forward were first

choices, so John Charles was drafted in as inside-right.

Danny Blanchflower led his Irish team adroitly and inspired them to

a lead after twenty minutes. The Welsh team of the time, however, was

full of players with skill and fight and fought their way back into

the game. Harry Griffiths, who had travelled to Leeds with Charles from

Swansea but been rejected, was on the left wing and on the half hour

he hooked the ball into the area, allowing Charles to slam a powerful

left foot shot home. Terry Medwin crossed from the right not long afterwards

and Charles headed in his second.

Charles came close to a hat trick, but selflessly set up Trevor Ford

for a third goal. He had done enough, however, to stamp his ability

on the memory of the Welsh selectors, and he was rarely out of the side

after that triumph, spearheading a particularly glorious time in Welsh

footballing history.

Six months later, Wales faced England at Cardiff and gave them a fearsome

run around, despite going down 4-1, and Charles had another supreme game.

Dick Ulyatt, the Yorkshire Post reporter who had enthusiastically

followed the player's glorious development at Elland Road, was gleeful

in celebrating the potential that was finally being realised in a red

jersey: 'All the Sunday newspapers I read yesterday commented that England

were lucky to win. Most of them said that the result was a travesty of

justice, some said this was the worst England side ever selected. All

said that John Charles was the outstanding player. One even said he must

be: "Written down as the greatest and most  artistically

efficient since Dean led the England attack. If it is insisted, as it

may be, that Lawton was as good as Dean, then Charles must be accounted

better than either."

artistically

efficient since Dean led the England attack. If it is insisted, as it

may be, that Lawton was as good as Dean, then Charles must be accounted

better than either."

'I quote that because for four years I have been saying much the same

of this genial giant who will not be 22 until the end of December and

any further praise from me may be accounted fulsome. I write it with great

satisfaction because when in the spring of 1950 Charles played at centre

half for Wales after I had cracked him up as the best centre half of my

time, he gave such a pathetically feeble exposition that the London critics

looked at me out of pitying and contemptuous eyes. This time I was able

to smile and say: 'I told you so' as they gobbled up all the details I

could give them of the great Charles' career and habits.

'Charles was as magnificent as the few soccer enthusiasts there are in

Leeds know he can be. He beat the sturdy centre-half Johnston nine times

out of ten in the air and nearly as often on the ground.

'A dozen times his headers or shots were either inches wide or saved

by the superb Merrick. He dummied to go to the left, passed to the right

and Davies pushed the ball on for Allchurch to score Wales' goal. He put

two passes at the feet of Davies which ought to have been shot into the

goal instead of high over it. At that stage it was unbelievable Wales

would lose; if it really had been Charles' day he would have scored five

or six goals and made several others.'

Ulyatt continued to be one of Charles' greatest champions and was glowing

in his praise again when Charles made his debut at Wembley in another

game against England in November 1954. The Welshmen were once more in

the ascendancy, but this time saw injuries to a couple of players leave

them vulnerable to an England fightback and a final 3-2 defeat. Roy Bentley

scored all three England goals but Ulyatt had eyes for only one performance:

'His second goal, which was the middle one of three scored in six minutes

during the second half, was an entirely different affair (from the tapped

in first), the ball going squarely to him from the touchline and John

taking it along the penalty area line with such deliberation that I thought

he would lose it. Eventually he transferred it to his right foot and then

cracked in a shot along the ground which had Wood beaten before he could

move.'

back to top

Those two fortunate England victories were avenged in October 1955 when

Wales won 2-1 at Cardiff to record their first victory against their opponents

since before the War. Wales took a two goal lead before Charles headed

in an own goal. He was overjoyed at the result and said of the error:

'Even that couldn't spoil the day. It is a day that will live long in

the memory of every Welshman who saw the match or played in it.'

Ulyatt again covered the match for the Yorkshire Post and was

as positive as ever: 'If there was an outstanding personality in this

game it was the young master - John Charles. He had Lofthouse under his

thumb; his coolness when others about him were losing their heads must

have been an inspiration; his poise as he cut out high centres with his

head left 60,000 Welshmen gasping with admiration. Charles today is the

uncrowned monarch of Welsh football. That he should give England their

goal when he headed a long cross by Byrne into his own net early in the

second half would have been football's greatest irony had it cost Wales

victory.'

Clearly the Fifties was a marvellous period for Wales but it was down

to the spirit and skill of some marvellous individuals who were motivated

and blended well by Manchester United assistant manager Jimmy Murphy,

who worked closely with Matt Busby at Old Trafford. Murphy was a wonderful

asset to the team with his inspirational approach, but the same could

not be said of the rest of the officials who ran the international side.

Few of them had a clue about football or knew the players in the Welsh

side. John Charles recalls the matter well and tells a tale about the

aftermath of a 3-1 defeat by Scotland at Hampden: 'We were sitting in

a lounge having a cup  of

tea after the game when one of our selectors came in and said: "Well

done, lads. You were far too strong for us today." We laughed and

said: "But Mr Owens, we're the Welsh team." On another occasion

we were flying off to a match when they found there weren't enough places

on the plane, so the officials all got on and made one of the players

wait for a later flight.'

of

tea after the game when one of our selectors came in and said: "Well

done, lads. You were far too strong for us today." We laughed and

said: "But Mr Owens, we're the Welsh team." On another occasion

we were flying off to a match when they found there weren't enough places

on the plane, so the officials all got on and made one of the players

wait for a later flight.'

The lack of organisation or know how only served to bring the players

closer together and they amazingly managed to make it to the finals

of the 1958 World Cup finals, held in Sweden. They did not do so, however,

without a degree of good fortune.

Wales, strictly speaking, only made it to the finals by default. They

had finished second to Czechoslovakia in their qualifying group. However,

in another qualifying group all of Israel's rivals refused to turn out

against them because of political objections. FIFA decided that the names

of all the group runners up should be put in a hat and one drawn out to

play the Israelis in a two-legged qualification tie. Wales were the lucky

team drawn out and they managed to win both legs 2-0, thus booking their

tickets to the biggest tournament in the world.

By now, of course, John Charles had exchanged the grimy streets of West

Yorkshire for the sunnier aspect of Turin in Italy, following a world

record transfer to Juventus in the close season of 1957.

Having laid out a fortune on their new star performer and seen him come

good almost immediately, the Italian club were understandably reluctant

to run the risk of excursions with Wales leading to injuries. The Welsh

team's management seemed apprehensive and timid about asking the Italians

to release Charles for the tournament and tried to get the player to sort

things out himself.

A stalemate dragged on and on and it was just four days prior to Wales'

opening game in the tournament, with Hungary, before he arrived in Scandinavia

to join his countrymen.

When Charles eventually landed in Stockholm after a badly disrupted flight,

it was the middle of the night and none of his country's representatives

were there to meet him, or even tell him where he needed to go. Charles

struggled helplessly at the airport for over an hour to find out where

he needed to go before a journalist took pity on him and gave him a lift

to the Welsh party's hotel.

However, his eventual arrival at Wales' headquarters brought fresh hope

to his countrymen and lifted everyone's spirits, as his brother Mel Charles

recalled in When Pele Broke Our Hearts by Mario Risoli: 'I'll never

forget it. John walked in. He looked like a Greek god because he was so

tall and bronzed. The selectors saw him, threw down their knives and forks,

stood up and started singing "For he's a jolly good fellow, for he's

a jolly good fellow." It was like a kids' party.'

The warm feelings didn't extend to the Hungarian players whom Wales faced

in their opening group match. They had clearly identified Charles as the

key man in their opponents' line up and set about kicking him out of the

tournament, with no regard as to the fairness of their tactics. They had

not figured, however, with the patience of Charles who steadfastly refused

to rise to their bating. He had the last laugh when he headed home an

equaliser to tie up the game. Hungary had started clear favourites and

had only four years previously been seen as the best side in the world

after their demolition of England and luckless challenge for the World

Cup in Switzerland.

The surprise success led to some complacency in the Welsh ranks for the

next game against an unrated Mexican team. Wales took the lead but allowed

their opponents to equalise a minute from time.

They were not too downheartened by the result, although they were naturally

disappointed. They had to face the hosts Sweden in the decisive final

game. Manager Jimmy Murphy took the view  that

a goalless draw would be enough to secure a play off place and set his

tactics for that result, withdrawing Charles first into midfield and later

the defence to stunt the Swedes' attack. It was ruthlessly unattractive

but totally effective in securing the point and indeed Wales did face

a play off with Hungary to go through to the last eight, a totally unexpected

achievement.

that

a goalless draw would be enough to secure a play off place and set his

tactics for that result, withdrawing Charles first into midfield and later

the defence to stunt the Swedes' attack. It was ruthlessly unattractive

but totally effective in securing the point and indeed Wales did face

a play off with Hungary to go through to the last eight, a totally unexpected

achievement.

It was so unexpected, in fact, that it caught the Welsh officials by

surprise - they had been sure that Sweden would beat Wales and had booked

flights home for after the game. They had to fly back from London the

next day after their monstrous gaffe and total lack of faith in an extraordinary

team.

back to top

Charles' devotion to his country's cause had made him only too happy

to play deep against Sweden, but he received an eye injury and had to

have four stitches before the game against the Hungarians who once again

dished out the treatment to him. It was a glorious performance, however,

and Wales came from a goal down to equalise through a 25 yarder from Ivor

Allchurch before Terry Medwin scored the winner. Charles played his part,

but a rough game had put paid to his World Cup. He finished the match

hobbling and was unavailable for the quarter-final against a brilliant

Brazilian side, boasting a bright 17-year-old called Pele among their

forwards.

It was Pele who toe poked home the only goal of the game, his first in

the World Cup finals. The famous Brazilian always referred to the goal

as 'the luckiest and most forgettable goal I ever scored'.

Many felt that it was the absence of Charles which was the deciding factor

and that if he had been fit to play there would have been a completely

different outcome. Tottenham's Welsh winger Cliff Jones: 'We had a very

good team in Wales in those days. John, Ivor Allchurch, with Terry Medwin

and me on the wings, Mel Charles at half back, Jack Kelsey in goal. I

look back at it and think we should have done a lot better than we did.

Individually we were quite as good as any other team but collectively

we couldn't quite put it together. I don't know why.

'I still think if John had played in the quarter final against Brazil,

we could have beaten them. People think I'm joking but I'm convinced of

it. I had my best game of the World Cup in that match, and Terry and I

provided plenty of service with crosses. Colin Webster came in at centre

forward. He was a good player but he was not John Charles. John would

have got on the end of one of those crosses. It's a certainty. And he

would have been very, very dangerous.'

Charles: 'Missing the Brazil match was the biggest disappointment of

my career, but playing for Wales was always very special for me. I always

wanted to pull on the shirt and represent my country. It was an honour.'

Unfortunately, the sad end to his World Cup career also marked the last

major highlight of his international days. He was still good enough to

play for his country for another six years, but neither Wales nor their

centre-forward ever again rose to their 1958 heights on the international

field. But for a time at least, in that golden period, Charles and his

glorious Wales side could as equals rightfully rub shoulders with the

best the world had to offer and not be found wanting. It was the most

wonderful and exciting time in Wales' footballing history.

An appreciation - Part

1 Welsh gold - Part 2 King Charles - Part

4 The Italian Job - Part 5 End of an Era

back to top

John

Charles broke through into the Leeds United side as a seventeen year old

in 1949 and earned rave reviews for his performance as an ever present

centre half in the team which ended 1949/50

an impressive fifth in the Second Division.

John

Charles broke through into the Leeds United side as a seventeen year old

in 1949 and earned rave reviews for his performance as an ever present

centre half in the team which ended 1949/50

an impressive fifth in the Second Division. two appearances. He finally made his mark on 15 April 1953 when he played

in Belfast against Northern Ireland.

two appearances. He finally made his mark on 15 April 1953 when he played

in Belfast against Northern Ireland. artistically

efficient since Dean led the England attack. If it is insisted, as it

may be, that Lawton was as good as Dean, then Charles must be accounted

better than either."

artistically

efficient since Dean led the England attack. If it is insisted, as it

may be, that Lawton was as good as Dean, then Charles must be accounted

better than either." of

tea after the game when one of our selectors came in and said: "Well

done, lads. You were far too strong for us today." We laughed and

said: "But Mr Owens, we're the Welsh team." On another occasion

we were flying off to a match when they found there weren't enough places

on the plane, so the officials all got on and made one of the players

wait for a later flight.'

of

tea after the game when one of our selectors came in and said: "Well

done, lads. You were far too strong for us today." We laughed and

said: "But Mr Owens, we're the Welsh team." On another occasion

we were flying off to a match when they found there weren't enough places

on the plane, so the officials all got on and made one of the players

wait for a later flight.' that

a goalless draw would be enough to secure a play off place and set his

tactics for that result, withdrawing Charles first into midfield and later

the defence to stunt the Swedes' attack. It was ruthlessly unattractive

but totally effective in securing the point and indeed Wales did face

a play off with Hungary to go through to the last eight, a totally unexpected

achievement.

that

a goalless draw would be enough to secure a play off place and set his

tactics for that result, withdrawing Charles first into midfield and later

the defence to stunt the Swedes' attack. It was ruthlessly unattractive

but totally effective in securing the point and indeed Wales did face

a play off with Hungary to go through to the last eight, a totally unexpected

achievement.