|

|

|

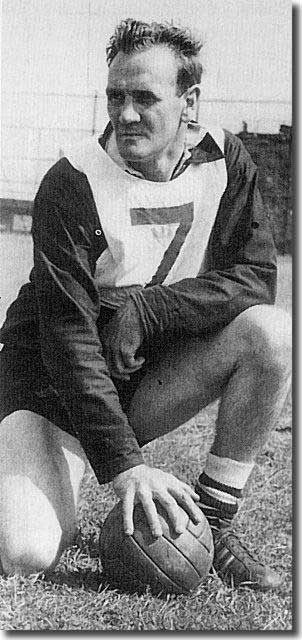

33-year-old former England inside-forward Don Revie was appointed manager

of Second Division Leeds United in March 1961 in an act of some desperation

by the West Yorkshire club. Since the irascible Major

Frank Buckley had departed in 1953, three other managers had come

and gone, with only Raich Carter achieving any

success, riding back to the First Division on the back of the goals of

John Charles. The incompetence of Bill Lambton and the poor

discipline of Jack Taylor had condemned Leeds

to relegation in 1960 and now it was Revie who had accepted the poisoned

chalice of leading a dispirited outfit. He combined the job with occasional

appearances on the field, but his pace had gone and his influence was

marginal. However, his sharp football brain and fascination with systems equipped

him well for the role of manager. He had formed a powerful bond with director

Harry Reynolds, who succeeded Sam Bolton as chairman in December 1961.

The bluff Yorkshireman indulged the whims and fancies of the new man and

supported an improvement in conditions for the players. It was a calculated gamble but enabled Revie to build a dynasty at Elland

Road. The unfaltering loyalty of Reynolds was what really made the difference

as the two men set about attracting the best teenage talent in the country

to enrich the squad. Lambton initiated a youth development scheme in his short spell at the

helm and the promising Scottish winger Billy Bremner was an early product.

If the idea had been his predecessor's, however, it was Revie who exploited

and nurtured the initiative. Revie and Reynolds travelled the length and

breadth of the country in search of new blood and were supremely successful

in the face of considerable opposition. Revie spoke enthusiastically of his plans: 'The long term outlook of

this club must be based upon youth. No players, however well intentioned

and conscientious, can possibly acquire the loyalty that all clubs need

to the same degree as those players who start their life with one club

and develop throughout the teams. We are basing our plans upon securing

the best youngsters there are available, and to that end all schools,

youth and junior representative matches are being watched and reported

upon.' He waxed lyrical about the young men who formed the club's Northern Intermediate

League side: "We think we have a young team well worth watching, but to

get the best out of them, they must be brought along gradually. It is

of course frustrating to a football supporter to be asked repeatedly to

be patient but I am afraid that is what is required ... the history of

football abounds with stories of clubs meeting with success when the days

looked darkest. In every instance it was to be found that the people in

charge were prepared to grasp success when the tide began to flow their

way." Perhaps Revie's biggest discoveries were the gifted Scottish forwards,

Peter Lorimer and Eddie Gray. Andrew Mourant: 'The signing of Peter Lorimer illustrates Revie's determination.

When Revie was tipped off that another club was all set to sign him, he

and Maurice Lindley left by car for Scotland at 8pm heading for Dundee.

They had to reach Queensferry by 11.30 to catch the final ferry across

the Firth of Forth. "Ours was the last car on," Revie recalled.

"At the other side we set off again - and I was stopped for speeding

as we hurtled through Perth in the middle of the night. Fortunately, the

policeman was a football supporter. We arrived at Peter Lorimer's door

at 2am, knocked up the whole house and signed him. At eight o'clock our

rivals turned up only to find they'd been beaten to him."' Eddie Gray: 'By May 1963, the trickle of English and Scottish League

clubs who had made approaches to sign me had become a flood. At the final

count, the total was thirty five, and included Everton, that season's

First Division champions; Tottenham, the 1961 championship and FA Cup

double winners, who were runners up; Manchester United, the FA Cup winners;

Liverpool, Arsenal and Chelsea. 'A major reason for my decision to join Leeds was Don Revie. His appreciation

of the art of PR was outstanding. When it came to making people feel special,

he thought of everything; he thought about things that I dare say would

go over the heads of a lot of other managers. It was typical of him that

to celebrate the decisions of Jimmy Lumsden and myself to join Leeds,

Don and Harry Reynolds came up to Glasgow and threw a party for us and

our families in the Central Hotel.' The promise of youth would take some time to mature, but in the meantime

Don Revie bought time by bolstering morale and team spirit. He opted for

a bizarre symbol of his ambition, exchanging the club's traditional blue

and gold strip for a pristine all white, with the stated intention of

importing a touch of the Real Madrid magic. It smacked of gimmickry and

was greeted with derision, but Revie would try anything to lift the sights

of his team above mediocrity, commenting later: 'I knew something had

to be done, so I thought we'd improve the image with a new strip, especially

an all white one like Real Madrid's and that gave me the chance to tell

them that I wasn't going to be satisfied until we had reached the same

stature as the famous Spanish club, and there was no future at Leeds for

anybody who didn't think that way. 'I said we had the potential to become a major force in English and European

soccer, though, honestly, just then I didn't think we had a cat in hell's

chance, but they'd got to start believing in themselves, and that was

another reason for the improved travelling plans because you can't tell

a team to aim for the sky, and then put them in a dingy boarding house

whenever they are away from home.' In the short term there was little improvement on the field, and Leeds

struggled against relegation for most of the season. While he was waiting

for his youngsters to emerge, Revie imported some old stagers, with Scottish

keeper Tommy Younger, Sheffield United full back Cliff Mason and Everton's

midfield firebrand Bobby Collins the most notable names. Revie was still

making sporadic appearances on the field, but played his last game that

spring, shortly before the arrival of Collins, and it was Younger who

prompted Revie to hang up his boots, saying: 'When I joined Leeds in September,

they were something like ten points worse off than any other team in the

League. Don was still playing and, as I was an outspoken type, I frequently

told him: "With the club in this state, I don't see how you can successfully

play and manage at the same time." He disagreed at first, but soon

realised he was trying to do far too much. I was sitting next to him on

the journey back to Leeds following a 2-1 defeat by Swansea early in the

season, and he told me: "You were right, Tommy, I've played my last

game for Leeds."' Collins arrived in time to replace Revie on the field and inspired a

closing In the final run in, two drawn games against Bury were vital, but in

later years it was alleged that Revie had tried to offer bribes to his

opponents. Andrew Mourant: 'It was a match that was to have a potent significance

some 15 years later, for around it circled an extraordinary story: namely

that Don Revie attempted to bribe Bury manager Bob Stokoe with an offer

of £500 for his team to forfeit the match in Leeds' favour. 'Chronologically, it was the first in a series of similar allegations

made by the Daily Mirror in September 1977, claiming Revie had,

on several occasions, tried to fix crucial matches in Leeds' favour with

the offer of financial inducements to opposing players. He denied all

of them, though while he initiated proceedings for libel, he never went

to court to clear his name. But Stokoe has no doubts. "I remember

the situation very clearly," he says. "He offered me £500 to

take it easy. There were no witnesses. I said no. And when I said no,

he asked me if he could approach my players. I said under no circumstances

... and reported it to my chairman and vice-chairman." 'Stokoe, an old-fashioned centre-half who had spent 14 years at Newcastle

before joining Bury as player-manager, is known in the game for his honesty.

He found Revie's approach peculiarly repugnant. "I was just starting

out in my managerial career... and I was never motivated by money. Though

anyone who knows Bob Stokoe will tell you he's fiercely competitive. I

have a reputation for being a bad loser. After that match, I lost all

respect for Revie. On that Tuesday night we went to Leeds, Revie never

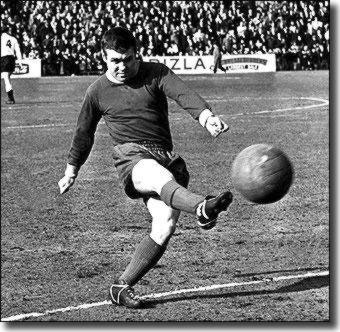

spoke. But I had one of the finest games of my life. We drew 0-0."' The signing of Bobby Collins was to prove a masterstroke for Revie. Everton

manager Harry Catterick discarded the former Scottish international as

he sought to rebuild his team, and rarely has £25,000 been better invested.

In the years that followed, Collins brought a new competitive edge to

the team. The Scot was a controversial but key figure as Don Revie's Leeds

United earned a reputation as a difficult team to play against. Jack Charlton: "He was only a little guy, about five feet six inches

tall, but he was a very, very strong, skilful little player. But what

marked him out, and what made the difference to the Leeds sides he played

in, was his commitment to winning. He was so combative; he was like a

little flyweight boxer. He would kill his mother for a result! He introduced

a sort of 'win at any cost' attitude into the team. Probably because we

had a very young side at the time, the other players were very much influenced

by his approach to the game. "Bobby introduced a much more professional attitude to winning. In the

past we'd often score a goal but then let the other side back into it.

Now we'd score a goal and that would be it - we'd lock it up, that was

the end of the game. Our defence was rock solid and we tackled hard. Nobody

liked playing against us. It wasn't very popular, of course. Teams like

Arsenal and Spurs might play to the gallery by chasing bigger scores,

but not Leeds United." Collins was to prove a wonderful signing, but at the start of the 1962/63

season Don Revie pulled off an even more high profile transfer, bringing

former striker John Charles back from Juventus in a startling £53,000

deal. Unfortunately, the move was a disaster and Charles could not come

to terms with a return to English football. After just eleven games for

Leeds, the Welshman was back off to Italy, signed for £70,000 by Roma. From such a bitter experience, however, Don Revie emerged all the stronger,

staking his entire hopes on youth. He brought in four teenagers, Gary

Sprake, Paul Reaney, Norman Hunter and Rod Johnson, for a match at Swansea

that yielded a much-needed victory. The gamble didn't end there as more

teenagers, Mike Addy, Barrie Wright, Jimmy Greenhoff and fifteen-year-old

Peter Lorimer, figured in the first team as Leeds enjoyed a wonderful

season, although a run of defeats in the closing stages saw an unlikely

promotion challenge peter away. The upturn in fortunes and rumours of other clubs courting their manager

were reason enough for the Leeds directors to offer Revie an improved

contract, making him the best paid manager outside the First Division,

and securing his services until 1967. The previous October there had been rumours that Revie was being lined

up as a possible successor The following season saw Leeds United kick off their march to the top

by securing the Second Division title, grinding out the points with a

series of extraordinary defensive performances. They eventually saw off

the challenges of Preston and Sunderland to win the championship, but

their performances were neither pretty nor appreciated by the neutrals.

Led by Collins, the side became uncompromising and notoriously difficult

to beat, earning regular criticism from the newspapers for their hard-edged

approach. Two signings made all the difference. Early in the season Manchester

United's Irish right-winger Johnny Giles arrived in a £35,000 deal, allowing

Billy Bremner to drop back to right-half, thus giving birth to the renowned

Bremner-Charlton-Hunter half-back line. The purchase of Giles was a masterstroke,

adding much needed class and craft to Revie's gang of youngsters. As a late season wobble threatened to derail the promotion push, the

manager got the chequebook out again, splashing £53,000 on Middlesbrough's

England centre-forward Alan Peacock. The striker brought a late rush of

goals (eight in his 14 games, only one of which was lost), calming the

nerves and securing success. The final statistics made interesting reading. The previous

few seasons had resulted in goals conceded of 74, 92, 83, 61 and 53, but

the total in 1963-64 was just 34, with only three defeats suffered, all

in away games. Gary Sprake kept 17 clean sheets in the League. The 63

points earned was a new club record. It might not have made attractive

watching, but Don Revie could look back with satisfaction on a job well

done. It is interesting to note the difference between Revie's approaches as

player and manager. In his days with Leicester, Hull and Manchester City,

Revie had favoured a positive, cultured and progressive approach, but

the need to secure promotion had prompted a rather different outlook,

built on rock solid defence, a stifling midfield stranglehold and doing

just enough to gain a precious lead. With Sprake in goal and a defensive rearguard of Reaney, Charlton, Hunter

and Bell, Leeds United offered few chinks at the back for opponents to

exploit, while Giles, Bremner and Collins formed one of the strongest

midfield combinations in the country, comfortably dominating most rivals.

Don Weston and Jim Storrie were workmanlike forwards, but the one player

of flair was the South African winger, the pacy and skilful Albert Johanneson,

who enjoyed a wonderful season. United could rely on him to buy them time

when the going got really tough. In truth, however, led by Collins, their

formidable enforcer, who 'pulverised the opposition with his resourcefulness,

vision and low cunning', Revie's eager young men rather relished squeezing

the life out of opponents after successfully intimidating them by dint

of their stamina and strength. Bagchi and Rogerson: 'In the early 1960's roughhouse tactics 'It's important to recognise that the team was not unaware of their growing

infamy - but neither did they glory in it. Indeed, the reputation did

some of the hard work, as teams would already be apprehensive about meeting

them weeks before a match. 'Not one of Revie's players will admit that their manager ordered them

to use violence to get their way. The strongest hint is Jack Charlton's

memory of Revie 'murmuring approvingly' as Jimmy Lumsden, a young apprentice,

told how he'd dished out "a real beauty" in a recent match.

The truth is that Revie didn't need to tell them. He encouraged ultra-competitiveness

on the training ground, saw that his own players were uncomfortable on

the receiving end of hard tackling and let them draw their own conclusions.

It was more moral ambivalence than depravity: he didn't tell them to do

it but he didn't stop them either.' Don Revie was unrepentant of his team's approach, seeing it as a necessary

evil: 'Bill Shankly once made an apt summing up of what Division Two football

is all about when he said: "You can't play your way out. You've got

to claw your way out." It hurts me to admit now, but Leeds certainly

clawed their way out of Division Two. Our championship success that season

was due to a defensive, physical style which made us probably the hardest

team to beat in the League. Once we got a goal I would light a cigar,

sit back on the trainers' bench and enjoy the rest of the game, secure

in the knowledge that it would need a minor miracle for the other side

to equalise. Maybe we did not exactly endear ourselves to the soccer purists

in those days, but we had to be realistic. Had we attempted to produce

the uninhibited, constructive football which is a hallmark of today's

Leeds team, we would probably still be languishing in Division Two.' There were questions asked in the summer, about whether such low tactics

would work against the more accomplished sides of the First Division -

most pundits expected Revie's raw youngsters to struggle. The manager

himself had few doubts, telling his men they had nothing to fear. He declined

to strengthen his squad, stating 'I intend to give the present team a

run in the First Division and am very confident about them in that division.' Jim Storrie: 'After winning promotion, most managers would talk in terms

of consolidation. He spoke in terms of finishing in the top four. He said,

"We will come up against some world class players but we will be

the best team in the league." So he had the optimists among the lads

thinking we would win the League and even the pessimists thought we might

finish halfway up.' Whether there were any doubts or not, the players gave no hint of uncertainty

on the field, opening up with a salvo of three straight wins, including

one against champions Liverpool. It steadied what nerves did exist, and

the rigorous preparation of Owen and Revie emphasised how to make life

difficult for opponents. By now, the legendary dossiers that were eventually

both notorious and derided had become a way of life for Revie's players. Don Revie: 'Towards the end of the 1963/64 season, I heard some good

reports about a young player, so I sent Syd Owen along to run the rule

over him. Well, the report that landed on my desk the following Monday

was a masterpiece! I had never before seen such a detailed breakdown of

a footballer. Syd had left nothing to chance. He outlined how good the

player was on his right and left side; the angles or lines along which

he tended to run with the ball; the shooting positions he favoured, and

so on. 'It struck us that a report like this would be invaluable if applied

to the teams we met each week, and it all started from there. Each week,

either Syd, Maurice Lindley or myself would watch our opponents for the

following Saturday. The report was typed on the Monday morning and we

would spend the rest of the week working on it with the players. 'On many occasions, we held practice matches in which the reserve players

adopted the same style of play as the team in question, and the first

team lads had to try and break it down. For example, if the opposition

did not read the game well at the back, we would practice decoy runs designed

to pull their defenders forward so that balls played over their heads

for Leeds players to run onto, that type of thing.' Jason Tomas included some excerpts from the dossiers in his 1971 book,

The Leeds United Story: '15 August 1964: Liverpool 2 West Ham United 2. Liverpool took the field

first and proceeded towards the Spion Kop end. This being the end they

prefer to defend in the first half, an advantage may be gained by getting

out first when we play there. Shankly has devised his team tactics to

cover some deficiencies in his playing strength. Both full-backs lack

pace and our wingers must seek the ball behind them. Liverpool depend

a great deal on centre-half Yeats, who sticks like glue to the centre-forward

and clears his lines decisively at all times. In this game both wing half-backs

played a very stereotyped game and should one go on attack, the other

stays back, even when an opportunity may arise to move with ease into

a position to change the point of attack. The Liverpool defence play square

with both full-backs endeavouring to keep close to the wingers even when

a strike is made through the inside positions. It was noticeable that

West Ham's inside-left Hurst was on to a number of balls behind the Liverpool

right-back in the first fifteen minutes and I could not figure out why

this approach was not sustained because it proved highly dangerous in

the early period. Balls into this area will probably be more productive

because of the two wing half-backs. Right-half Milne tends to advance

more than Stevenson. It was Yeats who was moving out to challenge Hurst

on most occasions.' The full report went on for pages and pages and pages and offered detailed

analyses of all the individual players. Some of the reports are particularly

scathing in their criticism of individuals: 'His whole attitude is wrong.

He lacks courage, has no desire to work and appears to treat his profession

as a big bore!' Leeds chose not to vary their style for the First Division, although

they had to start without Alan Peacock, missing until late February after

a cartilage operation. Peacock's absence robbed them of a vital goal supply, but Storrie and

Weston managed enough between them to propel the team into a surprisingly

high position, confounding the doubters. However, there was a noticeable

cloud on the horizon. Andrew Mourant: 'The season was less than two months old, and Leeds United

about to run into their richest vein of form yet, when, on 16 October,

a newspaper story leaked out that Revie was preparing to abandon Elland

Road for the managerial vacancy at Sunderland. The following day there

was, for its time, a vociferous and impassioned demonstration of Leeds

supporters after the 3-1 home defeat of Tottenham. That evening Harry

Reynolds was injured in a car crash returning from another match in Yorkshire.

Revie was among the first of his hospital visitors. While the Leeds manager

was later to be saddled with a reputation for greed, Reynolds' daughter,

Mrs Margaret Veitch recalls him saying: "It's not about the money."

As much as anything, Revie appeared to crave recognition. From his bedside,

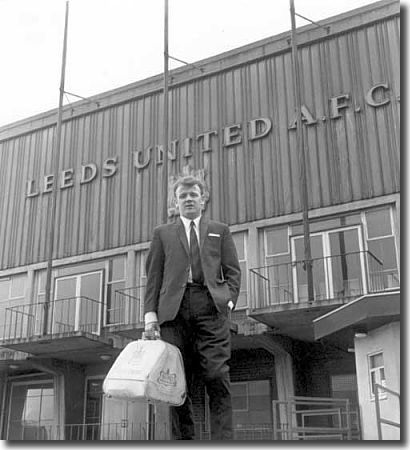

Reynolds, who favoured Revie winning an improvement in his Revie had applied for the vacancy at Roker Park because the Leeds board

would not grant him a five-year contract, but changed his mind before

they could even reconsider. He claims: 'I had landed the Sunderland job,

and was walking into the locker room at Leeds to collect my kit when I

came face-to-face with a group of newly-signed apprentices. Believe it

or not, they had tears in their eyes when I told them I was leaving, and

that touched me. It might seem trite to say that I looked upon my players

as sons, but this is true. Most of them had been with the club since they

left school, and I promised their mothers and fathers I would look after

them. I had repeatedly stressed the importance of loyalty to these lads

and thought: "They've been loyal to you, so it's up to you to show

the same loyalty in return."' The United team was involved in a number of notorious onfield battles

that season as they sought to assert their authority. Leeds were usually

painted as the aggressors, the outlaws, the kickers, the barbarians, but

there were other players who were equipped to dish out the violence and

on many occasions the Whites simply escalated a conflict that others had

provoked. In November Bobby Collins led his team to Everton for his first return

to the club he had left in 1962. The match was chaotic and spiteful from

the off with Jack Charlton a victim of a foul in the opening sixty seconds

and Goodison full-back Sandy Brown dismissed after five minutes for a

foul on Johnny Giles. Willie Bell headed Leeds ahead after 15 minutes,

provoking outright hostility from the home supporters and an increasingly

fractious contest. Bell and Everton forward Derek Temple clashed on the

wing ten minutes before the interval and a full on battle commenced, forcing

referee Roger Stokes to send the teams from the pitch to cool down. The contest remained confrontational and bitter but there were no more

goals and Leeds had won the fifth in a sequence of seven straight victories.

They lost the next match 3-1 at West Ham, but remained unbeaten in the

next 18 games in the League to propel themselves into astonishing championship

contention. They also proved particularly durable in the FA Cup, as they

battled their way through to a semi-final against Manchester United, also

their biggest threat for the League title. The match at Hillsborough was another torrid, violent affair, punctuated

by a series of spiteful, irritable individual battles. The contest between

Jack Charlton and Denis Law was particularly heated, with Law going off

missing most of his shirt, while Billy Bremner and Paddy Crerand were

nip and tuck throughout. Albert Johanneson limped through the majority

of the game after Nobby Stiles hammered him early on. The battle finished

without a goal. Four days later the replay in Nottingham was also drifting towards a

0-0 stalemate in a slightly less ferocious encounter until Leeds broke

the deadlock in the 89th minute. Bremner, with his back to goal, contrived

to flick home a Giles free kick with his head to give Leeds a place at

Wembley against Liverpool. As commentator Kenneth Wolstenholme noted,

"Don Revie's gone mad," ecstatic with the joy of taking his team to the

showpiece occasion. The mood was less buoyant, however, when Leeds lost 1-0 at home to their

greatest rivals in the League to relinquish the advantage that they had

so manfully earned. Despite recovering from the setback, Leeds relinquished

their challenge during Cup final week when they allowed lowly Birmingham

to take a 3-0 lead. Elsewhere Manchester United were winning 2-1 against

Arsenal and still had a game in hand, so Revie signalled for his players

to take the foot off the throttle and save their energy for the Cup final,

resigned to the knowledge that their title ambitions were over. Amazingly,

Leeds fought their way back and snatched a thrilling 3-3 draw, with only

the post denying Norman Hunter an injury time winner. The title was lost, although Leeds were confirmed as runners-up, second

only on goal average, in the most hotly contested title battle for years.

The points total of 61 was the greatest ever for a team coming second,

but that was no consolation, as Leeds ended the season with nothing to

show for their efforts. They never settled at Wembley against Liverpool,

with too many players freezing on the day and lost 2-1 after extra time,

despite Bremner equalising after being pushed forward. Bobby Collins was elected Footballer of the Year, surprisingly, perhaps,

after all the rancour of his performances throughout the season. It at

least left some mark on a remarkable year when Leeds United had come closer

than they had ever done to success at the highest level. Don Revie had

every reason to be content. Remembering his own disappointments as a player with Manchester City

a decade earlier he raised his squad's spirits, pointing out how far they

had come and that there was always another year. The players were still

learning their trade and had frightened the life out of the game's higher

echelons, onfield and off. The manager had the intense satisfaction of

knowing that his men had qualified for European competition and the chance

to compete on foreign fields. The second place finish had brought an Inter Cities Fairs Cup place and

Leeds kicked off with a difficult challenge against the strong Italian

side Torino. The first leg was at Elland Road and Leeds emerged with a

2-1 victory. It seemed unlikely that the European novices could survive

the second leg, particularly when Collins was viciously removed from the

game by Poletti who leaped on him in an off the ball incident, shattering

his femur. The incident caused a near riot as the Leeds players protected their

skipper from the attempts of the Italians to have him dragged screaming

from the pitch. The ten men could have been forgiven for wilting under

the pressure, but they rallied and defied their opponents for the remaining

40 minutes to earn a goalless draw and a place in the next round. The loss of Collins was a grievous one. Revie's answer to the problem,

part luck, part sound judgement, was to move Johnny Giles from the right-wing

into Collins' playmaking role and promote Jack Charlton to captain. He

filled the right-wing berth vacated by Giles by buying Huddersfield Town's

England winger Mike O'Grady, and also brought Paul Madeley, Terry Cooper

and Peter Lorimer through from his junior ranks, subtly changing the shape

and approach of his side, as form and injuries restricted the contributions

of Albert Johanneson and It would have been understandable if such disruption had led to a loss

of momentum, but United once again finished runners-up in the League,

this time to Liverpool, although in reality Leeds were never close enough

to present a serious threat. It was a different story, however, in the

Fairs Cup as the team belied its inexperience in this strange European

environment by working their way through to the semi-finals. Their route to that stage brought further evidence of the violent nature

of life with Leeds. Andrew Mourant: 'The third round Fairs Cup tie against Valencia at Elland

Road on 2 February 1966 erupted into spectacular violence 15 minutes from

time with the tie at l-l. Jack Charlton had advanced in support of a Leeds

attack when he was kicked by a Spanish defender. Then he was punched;

and then, in his own words, he lost his head. The brawl that ensued brought

police on to the pitch, and, for the second time in little over a year,

Leeds and their opponents were taken off the field by the referee so that

rage and fury might subside. The match ended with Charlton and two Spaniards

being sent off. 'The controversy rumbled on long after the final whistle. In its midst

were Revie and Dutch referee Leo Horn who, in Peter Lorimer's view, had

lost control of the game. According to Horn, Revie had begged him not

to send Charlton off with the words: "Do you know what you are doing?

He is an international." Revie denied the exchange ever took place.

In any event, Mr Horn did not referee the return leg in Spain, for which

forecasts of horrific combat had been made. Instead, there was a disciplined

performance by Leeds whose 1-0 victory emphasised a growing maturity.' The semi-final draw paired Leeds with another powerful Spanish team,

Real Zaragoza. Johnny Giles was dismissed near the end of the first away

leg, but the sides could not be separated, and the tie went to a replay

before the Spanish team eventually despatched their opponents to leave

United once more with nothing to show for their season long efforts. Don

Revie again accentuated the positives. The lack of trophies troubled him,

however. There was little improvement in 1967, despite Jack Charlton's election

as Footballer of the Year. Leeds suffered many problems with injuries

and also had to withstand the departure of Bobby Collins, freed to Bury.

They finished fourth in the League, and bowed out of the League Cup on

the wrong end of a 7-0 mauling by West Ham, a result that cut Don Revie

to the quick. He rounded on his shattered team and drove them on in the

other two Cup competitions. He often refused to accept their pleadings of injury and forced many

to play when they were walking wounded, Billy Bremner particularly so,

as the new captain noted: 'Over the years, a good 70 per cent of the lads

have played in games where they shouldn't have done. I remember the Cup

game against Sunderland that season. I had had my knee ligaments done

at Southampton the previous Saturday. A week for knee ligaments is impossible

... there is no way you can do it. When the team went up on Friday and

I was on the team sheet, I thought: "I don't believe this." 'We went up to Sunderland the night before. At ten o'clock in the morning,

Les Cocker came to my room and said: "Billy, we're going to have

a fitness test." We went down and Les did a couple of block tackles

on me and nearly killed me. I came off and said: "There's no way

I can play, honestly." But the Boss said: "I'd rather have you

with one leg than anybody else with two." So I went out and played,

and I tell you, I had a disaster. I stayed out on the right-wing most

of the game. After, the Boss said: "I didn't have you out there to

play you know." I said: "For Christ's sake, what did you have

me out there for?" Leeds endured desperate fortune in the FA Cup semi-final battle against

Chelsea, when referee Ken Burns disallowed Peter Lorimer what looked like

a legitimate equaliser. The Londoners were leading through a Tony Hateley

header, when Leeds were awarded a free kick in the closing seconds. Johnny

Giles squared it to Lorimer who thrashed it home, only for referee Ken

Burns to order him to retake it, claiming that the Chelsea wall was not

ten yards from the ball. Revie and his men were apoplectic were rage,

but all their protests were waved aside by a steadfast official. Don Revie: 'I could have understood him not allowing the goal had Johnny

taken the free kick immediately. But after studying films of the incident,

it is noticeable that several seconds elapsed between Burns awarding the

kick and Johnny taking it. He left plenty of time for the Chelsea lads

to get back, and they must have felt the goal was fair because from where

I was sitting, no one appealed. In fact, one or two of them clasped their

heads in their hands in disappointment. We were sick - all football professionals

should take these things in their strides I suppose, but let's face it,

Wembley is their Mecca. It's terrible to lose your chance of playing there

in such an unsatisfactory manner. For about half an hour after the final

whistle, I felt completely numb. But the remorse really began to hit me

when I met my son, Duncan, outside the ground. He was sobbing - and I

felt like sitting down and crying with him.' Leeds went a stage further in the Fairs Cup, battling their way through

to the final where they were to face Dinamo Zagreb, among Europe's elite

clubs. Revie's caution got the better of him on the big occasion. The

first leg, away from home ended in a 2-0 defeat. Many managers would have

gone for broke in the return match, but Revie was different. According

to Mike O'Grady: 'He was really cautious, despite the away result. For

one thing, he had Paul Reaney on the right wing but also he filled our

heads with the opposition. I was a winger yet he was warning me about

the other winger ... expecting me to operate defensively as well as up

front. You'd be sitting there thinking: "God, just let us play!"' In the end, it mattered little as Zagreb played a perfect possession

game at Elland Road, offering few chances and securing a goalless stalemate,

thus winning the trophy on aggregate, leaving United empty handed once

more. It might have been better for Leeds if they had not been quite so consistent.

The very fact that they were continually in at the death of so many competitions

undoubtedly cost them results through sheer fatigue. It was not in Revie's

make up to admit defeat at anything and he insisted that they treat all

fixtures with the utmost seriousness. If anything, the breadth of the

challenge was even wider in 1968, as they battled to the death for four

different trophies. However, they would finally be more than bridesmaids. Part 1 An Appreciation - Part

2 Learning the ropes 1927-51 - Part 3 Centre

stage with City 1951-56 - Part 4 Shuffling off

stage 1956-61 - Part 6 The agony and the ecstasy

1967-74 - Part 7 Inn-gerland! 1974-77 - Part

8 Disgrace and despair 1977-89 Part

1 An Appreciation - Part 2 Learning the ropes

1927-51 - Part 3 Centre stage with City 1951-56

- Part 4 Shuffling off stage 1956-61 - Part

6 The agony and the ecstasy 1967-74 - Part 7

Inn-gerland! 1974-77 - Part 8 Disgrace and despair

1977-89

Part

1 An Appreciation - Part 2 Learning the ropes

1927-51 - Part 3 Centre stage with City 1951-56

- Part 4 Shuffling off stage 1956-61 - Part

6 The agony and the ecstasy 1967-74 - Part 7

Inn-gerland! 1974-77 - Part 8 Disgrace and despair

1977-89 unbeaten

run which was enough to stave off the drop, although a last day win at

Newcastle was required to confirm survival.

unbeaten

run which was enough to stave off the drop, although a last day win at

Newcastle was required to confirm survival. to

Walter Winterbottom as England's team manager. Revie had said at the time:

"As far as I am concerned it is ridiculous even to mention me for the

job. I am very happy at Leeds - even with all the ups and downs. What

I want to do is put Leeds back on the Soccer map."

to

Walter Winterbottom as England's team manager. Revie had said at the time:

"As far as I am concerned it is ridiculous even to mention me for the

job. I am very happy at Leeds - even with all the ups and downs. What

I want to do is put Leeds back on the Soccer map." were accepted practice, and there was a thin line between standing up

for oneself on the pitch and getting your retaliation in first. What Leeds

set out to do was not nihilistic: it was a hyper-aggressive game plan

destined to flourish by pushing the very limits of the law. The suspicion

that Revie dictated all this is the fundamental impediment when football

aesthetes discuss his credentials for "greatness".

were accepted practice, and there was a thin line between standing up

for oneself on the pitch and getting your retaliation in first. What Leeds

set out to do was not nihilistic: it was a hyper-aggressive game plan

destined to flourish by pushing the very limits of the law. The suspicion

that Revie dictated all this is the fundamental impediment when football

aesthetes discuss his credentials for "greatness". terms

and conditions, was pleased to hear of the volatile scenes at Elland Road.

These would, he felt, help sway board members who possibly valued their

manager less highly than he did.'

terms

and conditions, was pleased to hear of the volatile scenes at Elland Road.

These would, he felt, help sway board members who possibly valued their

manager less highly than he did.' Alan

Peacock.

Alan

Peacock. He

said it was to gee the other lads up, that they would have dipped without

me. I thought: "What a load of bullshit!"'

He

said it was to gee the other lads up, that they would have dipped without

me. I thought: "What a load of bullshit!"'