Part 1 A season from Hell - Part

3 - Back from the brink - Part 4 End of

an era - Results and table

The financial crisis that engulfed Leeds United Football Club at the

start of the 21st Century is one of the most amazing stories ever of money

in football.

The April 2004 edition of Four Four Two magazine contained a detailed

and in depth analysis of the story by Chris Britcher, which painted a

tale of misjudgement, negligence and ineptitude beyond belief, and is

reproduced here in full, sickening detail.

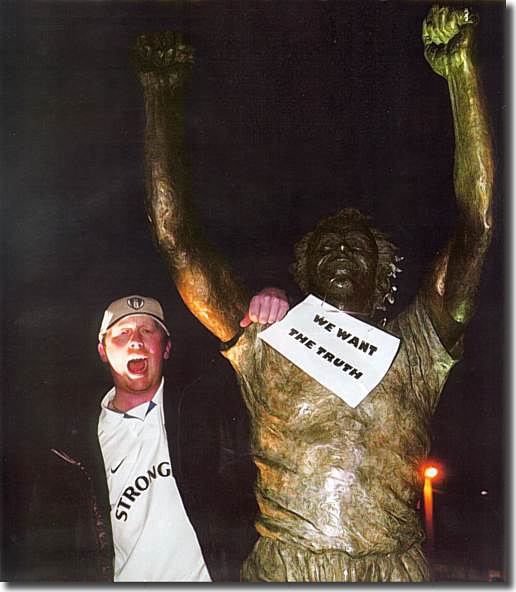

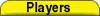

5 February 2003. In the upstairs of a crowded Leeds city

centre pub, Leeds United fans have gathered to hear news of the club's

emerging financial dilemma. Dr Bill Gerard, a professor at the Leeds University

Business School, has been invited by the Leeds United Independent Fans

Association to provide his expert analysis of the problem and address

the audience.

The crowd of several hundred are concerned. The team's form has slumped

and key players are being sold. What is more, the financial situation

at the club is becoming increasingly serious.

Gerard is a season ticket holder and small shareholder in the club he

has followed since moving from Glasgow in the '70s. His expertise in economics,

and football finance in particular, has made him well qualified to explain

what is going on.

Just before he is due to appear, he is handed a letter, signed by the

club's operations director David Spencer. Having worked for the club on

a number of issues over the years, he assumes it is reminding him to respect

confidentiality agreements he has signed. Gerard, who had no intention

of breaching such terms, duly opens the envelope.

To his surprise, it is not a gentle reminder, but a stark warning: should

he decide to use this platform to suggest that the sale the week before

of Jonathan Woodgate to Newcastle United was a result of financial problems

at the club, he will be sued.

Gerard is stunned and insulted. His speech is centred on publicly released

documents. His speech will pull no punches. His speech warns of impending

apocalypse.

One year on, events have proved him absolutely right. So just how did

Leeds United end up in the perilous position they find themselves today?

In 1996, thanks to the summer's Euro 96 tournament, the

football bubble was still being inflated. With Sky money buoying the marketplace,

and transfer fees promising high returns on top talent, owning a leading

football club seemed like route one to untold riches - especially if it

was led by successful businessmen who could exploit the numerous revenue

streams available.

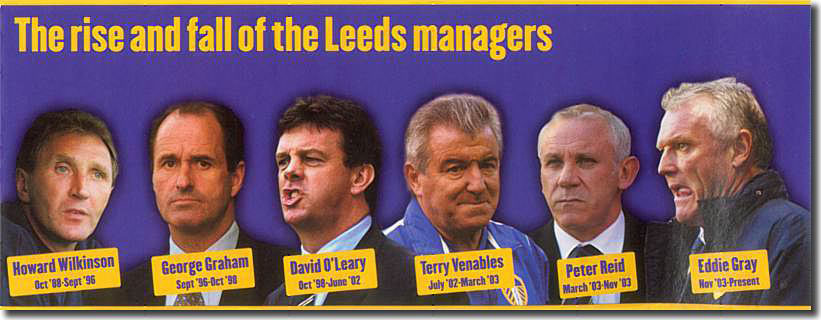

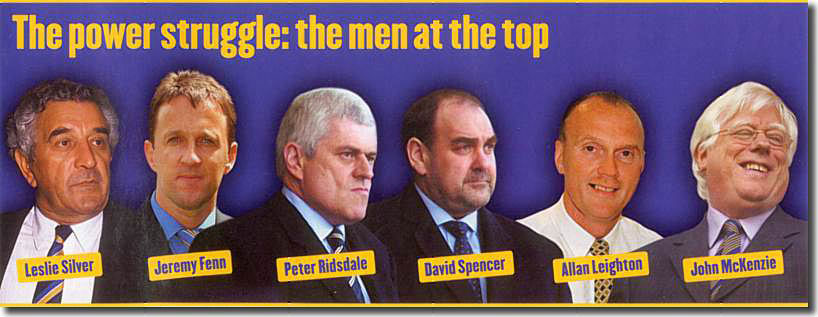

Yet for Leeds United the past three years had been a struggle. The championship-winning

team of 1991/92 had not only failed to build on victory but slipped away.

The fans were growing restless, and after Leeds lost 3-0 to Aston Villa

in the 1996 Worthington Cup final, the man who had led them to championship

glory, Howard Wilkinson, found himself being booed by Leeds fans at Wembley.

Later that summer a small but ambitious media rights company called Caspian,

whose portfolio included the rights to Paddington Bear and The Wombles,

identified Leeds as a perfect example of where a bit of investment and

a buoyant market could result in healthy returns.

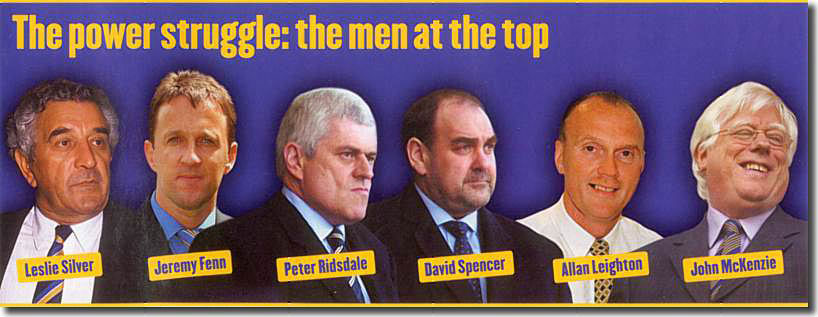

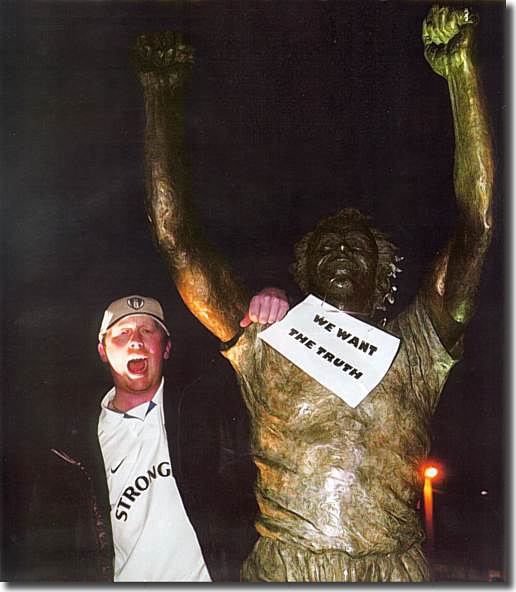

After checking out a number of other clubs, Caspian chairman Chris Akers

and his partners, Jeremy Fenn and former QPR chairman Richard Thomson,

presented the club's owners Bill Fotherby, Leslie Silver and Peter Gilman

with a £16m takeover proposal. The deal was done.

Caspian set about revolutionising the club, heralding their arrival as

a 'new dawn' for the club. Said Fenn at the time: 'The club wasn't in

the best shape when we bought it. Like a lot of football clubs it was

populated by people who were friends of friends; there was no discernible

management structure.'

Although many fans were anxious about the takeover, the Caspian plan

was grounded in sound business sense. Build the club up slowly but surely,

increase revenue streams off the pitch by investing in Elland Road, and

then allow profits to be sensibly spent on building a strong team both

on the pitch and in the boardroom.

back to top

That August, Caspian took the club public, changing its name to Leeds

Sporting to reflect a multi-faceted future. Floating on the stock exchange

is a good way of raising funds in the short term, securing equity in the

long term and becoming more transparent: a public limited company must

publish its accounts and make key news and developments that may impact

on its share price available to the marketplace. As a result of the greater

transparency and assumed tighter business discipline, banks and lending

institutions are more likely to do business. It also gave Leeds United

fans the chance to own a piece of the club - albeit a sliver.

Said Caspian chairman Chris Akers at the time: 'I took the view we had

to build a broader base and only those clubs which had the development

potential on site would be capable of that. They had to be big sites,

big brands with the opportunity to build something beyond pure football.'

For Leeds that meant turning the Elland Road site into a major commercial

hub, with a 250-bed hotel, entertainment and leisure facilities, a conference

centre and even a hockey pitch to expand the sports platform.

But for many fans, Howard Wilkinson was not a name that sprang to mind

when you considered the idea of a new dawn. Despite assurances, his time

at the club was running out. When Caspian first took over it gave him

a modest kitty to prepare for the 1996/97 season. Among those Wilkinson

lured to Leeds were a young Lee Bowyer from Charlton for £2.6m and goalkeeper

Nigel Martyn for £2.25m from Crystal Palace. Both were to play key roles

for the club. One would be instrumental in one of the key moments in the

club's long history and play a significant role in the biggest crisis

it has ever suffered. The other just kept goal.

But the new season continued in much the same vein as the last, and after

a thumping 4-0 home defeat by a Cantona-inspired Manchester United, the

P45 was dug out of the filing cabinet and presented to Wilkinson. George

Graham was drafted in to take the reins - his first managerial position

since leaving Arsenal in disgrace following the bung scandal.

Though

Graham transformed a leaky defence, his team closed up at the other end,

too, scoring just 28 goals in 38 league games and ending in 11th place.

The fans, sensing this cautious approach was worth their patience, remained

positive.

Though

Graham transformed a leaky defence, his team closed up at the other end,

too, scoring just 28 goals in 38 league games and ending in 11th place.

The fans, sensing this cautious approach was worth their patience, remained

positive.

Off the pitch, the new management team were taking things equally cautiously.

Caspian knew a sensible approach to the books would provide a firm footing

for investment and scope for redevelopment of the Elland Road site. They

had also appointed a long-time Leeds United board member to the position

of chairman. Peter Ridsdale, a man well known locally, grasped his new

position with gusto. Finally he was in a position to really shape the

future of his beloved Leeds. He was charismatic, enthusiastic and had

an uncanny ability to make people see things his way. A former managing

director at Burton's Top Man chain, he was vital to securing sponsorship

from the retail brand. He sold himself to the supporters as a life-long

fan, but crucially one with strong business sense in whose hands the club

was safe. With the added promise of developing a team of which the fans

could be proud, he had little difficulty winning them over.

The 1997-98 season saw Graham's dour defensive tactics change and suddenly

Leeds started looking like a team going places. Doubling the previous

season's goal count, Graham steered them to fifth in the league and a

UEFA Cup spot.

It was just what the new regime had hoped for. The club got a bigger

slice of Premier League sponsorship and Sky revenues thanks to their final

position, and had Europe to look forward to. It was all money in the bank.

And the youth system was producing some seriously mouth-watering talent

under the protective wing of former playing favourite Eddie Gray.

At board level, it was all painting a very positive picture for a management

team spearheaded by Fenn as finance director and Adam Pearson as commercial

director, both well-respected businessmen with a key grasp of the basic

'grow slow and steady' strategy. (Akers had already taken a back seat

to move on to his next project - exploiting the dot.com boom with his

Sports Internet Group.)

They set about trying to forge a real brand value in the Leeds United

name - a common mantra on the administrative side of modern football clubs

and not an easy task for a club like Leeds. With a rogue element of supporters

who had dragged their name through the mud on numerous occasions, for

many the Leeds team of the '70s with its 'bite-yer-legs' reputation still

epitomised what the Yorkshire club stood for. But if the hardly squeaky-clean

Manchester United and Liverpool could generate sizeable incomes from enhancing

their image and global appeal, Leeds reasoned they could too, and started

wooing businesses and investing in community projects in a bid to establish

Brand Leeds. Playing the community card was not only a wise move to get

more fans through the turnstiles and spending more money on club merchandise,

but also ensured a positive reaction for ambitious stadium plans in the

pipeline - a crucial part of its long-term strategy.

On

the pitch, meanwhile, the 1998-99 season was disrupted early by the departure

of George Graham back to north London with Spurs. As assistant to Graham,

David O'Leary had shown promise after assuming the caretaker-manager position

and he was offered a full-time contract with Eddie Gray as his assistant.

Unlike Graham, O'Leary was not afraid to introduce young blood to the

Leeds team. At his disposal were the likes of Lee Bowyer, Harry Kewell,

Alan Smith, Ian Harte and Jonathan Woodgate as a balance to experienced

squad members such as David Batty, Lucas Radebe and Gary Kelly. For the

plc, the double-edged bonus was that the young talent would eventually

either deliver riches on the pitch or profits off it courtesy of the still

booming transfer market. Ideally both.

On

the pitch, meanwhile, the 1998-99 season was disrupted early by the departure

of George Graham back to north London with Spurs. As assistant to Graham,

David O'Leary had shown promise after assuming the caretaker-manager position

and he was offered a full-time contract with Eddie Gray as his assistant.

Unlike Graham, O'Leary was not afraid to introduce young blood to the

Leeds team. At his disposal were the likes of Lee Bowyer, Harry Kewell,

Alan Smith, Ian Harte and Jonathan Woodgate as a balance to experienced

squad members such as David Batty, Lucas Radebe and Gary Kelly. For the

plc, the double-edged bonus was that the young talent would eventually

either deliver riches on the pitch or profits off it courtesy of the still

booming transfer market. Ideally both.

With a team performing well and playing attractive football, Leeds were

emerging as a major force again. Ridsdale and co. seemed to be vindicated.

back to top

By the end of the 1998/99 season, O'Leary's first in charge, Leeds finished

in fourth place, qualifying for the UEFA Cup. More crucially for the directors,

turnover was rising and profits were on the up.

Although the stated strategy was to grow slowly over the long term, the

team seemed now only one or two league places away from a potentially

lucrative Champions' League spot, which offered a huge temptation to force

the pace. In short, Leeds were drifting towards the verge of a dash for

growth.

According to Jeremy Fenn, Ridsdale - encouraged by an ambitious David

O'Leary - started the push for more player investment: 'In the summer

of 1999, I was still running the club but Peter Ridsdale was getting more

involved in the transfer deals, and it was quite clear there was a desire

on the part of Ridsdale and the manager at the time to spend more money

on players. Things came to a head when there were some stories in the

paper about myself constraining progress at the club through a lack of

desire to open up the chequebook, and I used that as an opportunity to

say this is not for me.'

It

is believed that Fenn, shy of the limelight and more content with simply

handling the behind-the-scenes business operation, was made to feel particularly

uncomfortable when O'Leary stated publicly that some of his moves for

certain players were being stifled by elements on the board. Fenn, who

remains proud of his reputation as a tough negotiator and book balancer,

was to become the first victim of what many saw as Ridsdale's move to

have more control of the club. He quit to reunite with Akers on his Sports

Internet Group.

It

is believed that Fenn, shy of the limelight and more content with simply

handling the behind-the-scenes business operation, was made to feel particularly

uncomfortable when O'Leary stated publicly that some of his moves for

certain players were being stifled by elements on the board. Fenn, who

remains proud of his reputation as a tough negotiator and book balancer,

was to become the first victim of what many saw as Ridsdale's move to

have more control of the club. He quit to reunite with Akers on his Sports

Internet Group.

It was to prove a major turning point in Leeds United's boardroom set-up,

heralding the beginning of the Ridsdale revolution.

'There was a gradual shift in the board,' says Bill Gerard. 'It was not

a coup in the sense of a sudden ousting of Caspian, but there was a move

away from those directors associated with it. I presume Ridsdale was behind

that.'

'The club was in fantastic shape at the end of 1999,' says Fenn. 'We

had a small debt, the club was profitable and we were performing well

on the pitch. We were trying to build the club carefully and sensibly

and part of that plan was to enhance the stadium in conjunction with the

development of an arena and widen the business perspective of the club.

I think we would have continued with a careful approach to building the

club in much the same way as Charlton have achieved with the consolidation

of their position within the Premier League.'

Adds Gerard, 'If the Caspian board had remained at Leeds, then I think

today we would not be in the financial situation that we are. I think

we would be financially stable, but I doubt we would have yet achieved

Champions League football. I think Fenn and Akers' objectives would have

been much more long term with respect to getting the quality of the squad

that we had in 2000.

'Peter Ridsdale realised that the future of football was going to be

a few top clubs who had a massive fan base and were able to maximise their

media income by playing in the Champions' League. He felt that if Leeds

did not get into the Champions' League and establish themselves quickly,

they would be left behind.'

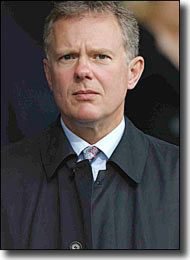

Adam Pearson followed Fenn out of the gates of Elland Road just 18 months

later. Today  chairman

at Hull City, he is convinced this period was crucial in Leeds' financial

downfall: 'It was a change of culture. Obviously I had been appointed

by Jeremy Fenn as commercial director at the football club and we had

built the club up on basic business premises which were to build the business

and keep the costs low. And obviously that culture changed considerably

over the coming years. I think we had just about maximised the turnover.

But then I could see the costs started to creep up and, after Jeremy's

departure, the way the club was run changed.'

chairman

at Hull City, he is convinced this period was crucial in Leeds' financial

downfall: 'It was a change of culture. Obviously I had been appointed

by Jeremy Fenn as commercial director at the football club and we had

built the club up on basic business premises which were to build the business

and keep the costs low. And obviously that culture changed considerably

over the coming years. I think we had just about maximised the turnover.

But then I could see the costs started to creep up and, after Jeremy's

departure, the way the club was run changed.'

That summer of 1999 Ridsdale became master of all he surveyed. As CEO,

and chairman of both the plc and the club, he was in control.

Following the departure of Fenn in July he recruited to the board those

loyal to him - in particular promoting Stephen Harrison to the post of

finance director and David Spencer to operations director. Soon to join

them as non-executive directors would be Allan Leighton and Richard North,

both highly respected in the City. A former chairman of Royal Mail and

non-executive director at BSkyB, Leighton's role at the club reinforced

the image of a strong, ambitious management team, driving Leeds into a

profitable future. 'The fans thought the club was in safe hands,' says

Gerard. 'They completely trusted Peter and the other board members.'

Other reasons to be optimistic were a £13.8m partnership with BSkyB,

whereby the media giant took a 9.9 percent stake in the team. Strongbow

signed up as shirt sponsors for 2000 in a £5m three-year deal, and Nike

agreed a new four-year kit and licensing deal.

By the time the team kicked off for 1999/2000

the strength of the side was obvious. They made it to the semi-finals

of the UEFA Cup before losing to Galatasaray, and finished third in the

league after spending many weeks on top, ensuring entry into the next

season's Champions' League. But then events began to overtake the plan.

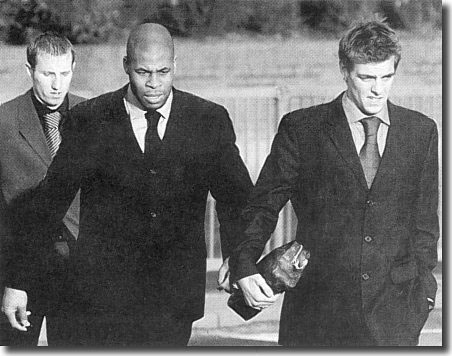

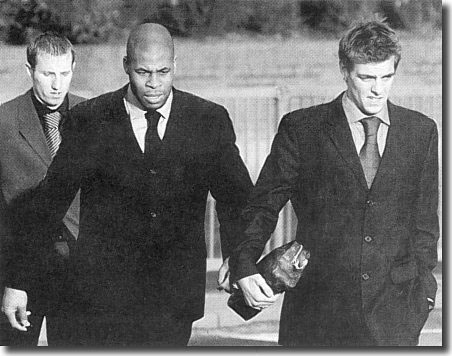

In January 2000, Lee Bowyer and Jonathan Woodgate, along with friends,

had attended the Majestyk nightclub in City Square, Leeds. Outside, trouble

had broken out and the pair found themselves arrested after student Sarfraz

Najeib was left in a bloody heap with a broken nose and cheekbone, fractured

leg and a bite on the cheek. Both protested their innocence. The

court case would not finally conclude until almost two years later,

with devastating results for all concerned.

Meanwhile, the stabbing to death of Christopher Loftus and Kevin Speight

after innocently getting caught up in running battles in Istanbul before

the Galatasaray match in April 2000 generated more negative headlines.

The football world united behind Leeds, with both Ridsdale and O'Leary

winning praise for their handling of the situation. Thrust into the spotlight,

Ridsdale became more synonymous than ever with the club.

back to top

Off the pitch, Ridsdale's strategy appeared to be working to perfection.

In October 2000 the club published figures which showed annual pre-tax

profits up a whopping 75 percent courtesy of the good UEFA Cup run and

sell-out crowds. Leeds Sporting reported pre-tax profits of £1.24m compared

to £0.7m the year before. To the outside world, Ridsdale was on a roll,

especially when the 2000/01 season maintained the momentum.

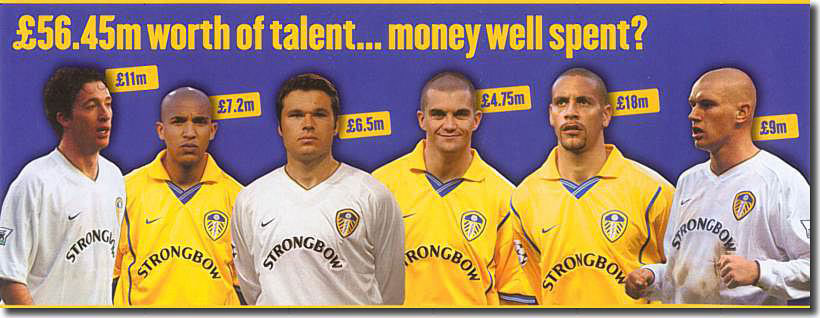

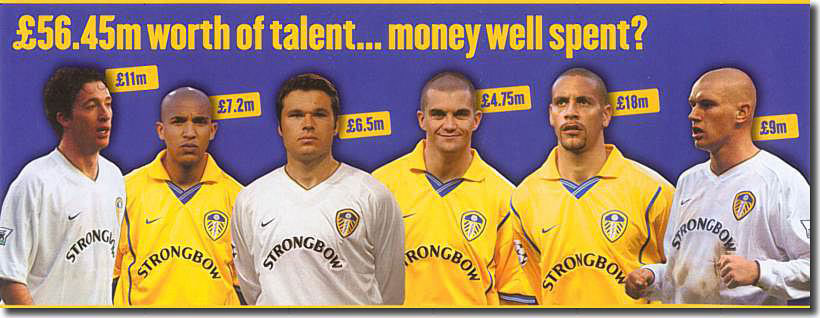

With a good run in the Champions' League as the prize, the push for more

players picked up pace. Before the end of the year, O'Leary had brought

in Mark Viduka (from Celtic) for £6.5m, Olivier Dacourt (Lens) for £7.2m,

Dominic Matteo (Liverpool) for £4.75m and, the piece de resistance, Rio

Ferdinand (West Ham) for £18m - a deal six months in the making and at

the time a world record price for a defender.

Crucially, the purchase of many of these players was conducted through

a company operated by former Manchester City full-back Ray Ranson. Registered

European Football Finance (REFF) allowed clubs to buy players on a hire-purchase

style agreement, which effectively saw Leeds rent their services. Although

Ferdinand was owned outright by Leeds, according to Ridsdale, Viduka and,

it is assumed, others were not. Leeds were not alone in using REFF, but

when the transfer market slumped they were suddenly left massively out

of pocket. Today Leeds still owes REFF some £20m.

But with a strong team built on homegrown talent and reinforced with

expensive young acquisitions, the view of the Leeds board was that should

they stumble, they could at least recoup the money through reselling their

players. Despite warning signs elsewhere in Europe, Leeds were not alone

in assuming the transfer market would continue booming.

On the pitch, meanwhile, a strong Premier League season was enhanced

by a Champions League campaign which will stay long in the memory of fans.

After victories against AC Milan, Besiktas, Anderlecht and Deportivo,

they blazed a trail for English clubs, going one step further than Arsenal

and Manchester United to reach the semi-final. For the board it was proof

the investment was all worthwhile. They had started out on a route to

riches - their Champions' League success

generated close to £10m from prize money and UEFA's lucrative marketing

pool alone. Brand awareness across Europe and increased sponsorship could

multiply that by several factors.

But despite the great performances in Europe, Leeds failed to make an

immediate return to the Champions League after coming fourth in the Premier

League. A blip rather than a disaster, the club would simply ensure that

by the end of the next season it was again preparing to kick-off a Champions

League campaign.

When the 2000-01 financial figures were released in October 2001 they

painted an interesting picture. Turnover was up 65 percent to £86.3m with

operating profits prior to player trading up a colossal 273 percent to

£10.1 m. But after taking  into

account the big buying, Leeds United plc - it had switched from its Leeds

Sporting name during the summer - posted a £7.59m loss against a £1.24m

pre-tax profit.

into

account the big buying, Leeds United plc - it had switched from its Leeds

Sporting name during the summer - posted a £7.59m loss against a £1.24m

pre-tax profit.

The results were good news for the directors. Richard North and Allan

Leighton rewarded Ridsdale with a £270,000 bonus on top of his £320,000

salary. Ridsdale took the opportunity of the finance figures to make it

clear what the club's future strategy would be: 'The absence of Champions'

League football this season will inevitably have a short-term impact on

operating profit. Rejoining the Champions' League at the earliest opportunity

is our top priority.'

It was a blinkered all-or-nothing approach, a gamble on immediate and

continuing Champions' League football, whose stake was a massive £60m

loan secured on the back of future season ticket and corporate hospitality

revenues predicated on a money-spinning new stadium. There was no Plan

B.

So the scene was set. Ridsdale and O'Leary had spent heavily on players.

There would be no Champions' League in 2001/02, but everything would be

done to achieve it by the end of the season.

The cracks were beginning to appear in the Ridsdale boardroom. Some suggest

North and Leighton were kept out of the loop when it came to the reality

of the situation. They would find out too late.

'The board all bought into the strategy and we put our trust in the executives,

whose day-to-day job it was to do these things,' explains Leighton. 'We

all thought the strategy was right at the time. Sometimes you get things

right and sometimes you don't.'

Falling into the latter category was a £20m punt on two players who would

embody all that was wrong with the inflated transfer market. Seth Johnson

was snapped up for £9m from Derby and Liverpool released Robbie Fowler

for £11m, bringing O'Leary's spending close to £100m in just three years,

much of it financed by funds raised for the proposed new stadium. Said

Ridsdale at the time: 'A lot has been made of whether this club is being

run effectively as a company. This is a public company and is being run

for its shareholders. The plc board are ensuring that the club is on a

sound financial footing and we are only investing in players who can keep

us near the top of the Premiership and in Europe.'

But by the turn of the year, all the investment still appeared to be

delivering the goods and the boardroom continued to buzz with anticipation

of what was to come. They were, said Ridsdale famously, 'living the dream'.

Inspired, the Leeds team took to the top of the table and all was well.

'Football is all about performance on the pitch, and performance had

been good,' recalls Allan Leighton. 'We'd strengthened the squad and the

view of the manager was that we would secure Champions' League. But that's

the frustrating thing about football - unlike any other business, you

cannot control the bit that makes the difference. All you can do is invest

in the strategy and hope it works.'

What was not needed at this delicate stage in proceedings was the attention

generated by  the

Bowyer/Woodgate trial. With one trial already called off after a Sunday

newspaper was guilty of contempt of court, it was not until December that

the jury got to make a decision - close to two years after the incident

involved. Ridsdale had decided to stick by the players until a verdict.

While Bowyer was cleared at Hull Crown Court of causing grievous bodily

harm with intent and affray, Woodgate was given 100 hours of community

service after being found guilty of affray. Their friend Paul Clifford

received six years for GBH. Evidence during the case painted a less than

pretty picture of both players.

the

Bowyer/Woodgate trial. With one trial already called off after a Sunday

newspaper was guilty of contempt of court, it was not until December that

the jury got to make a decision - close to two years after the incident

involved. Ridsdale had decided to stick by the players until a verdict.

While Bowyer was cleared at Hull Crown Court of causing grievous bodily

harm with intent and affray, Woodgate was given 100 hours of community

service after being found guilty of affray. Their friend Paul Clifford

received six years for GBH. Evidence during the case painted a less than

pretty picture of both players.

For all the efforts of the Caspian management board and subsequent development,

the brand name and image of Leeds United was once again tarnished. This

would cost more than anyone could have anticipated.

back to top

If that was not bad enough, David O'Leary then published a book just

days after the verdict. Leeds United On Trial was a look back at

the 2000/01 season - but its timing and comments on the team and the Bowyer

and Woodgate case were devastating to both the club and dressing-room

morale. It seemed Leeds were pressing the self-destruct button.

With a number of big name absences, and Bowyer being transfer listed

after a contract row, form started to slide. From being top at the turn

of 2002, Leeds eventually finished fifth - once again missing out on Champions'

League football. With the transfer market now in a slump, it was a catastrophe

which left the club stranded with no way of recouping its outlay. For

the first time the boardroom atmosphere dipped. 'The original strategy,

if the marketplace hadn't changed, was robust,' says Leighton. 'It was

a combination of missing the Champions' League, investing in a squad we

thought would put us in the Champions' League and then the change in the

transfer market - the introduction of transfer windows and fees dropping.'

Worse, the wage bill was sky-high. Determined to keep a strong squad

together after the first Champions' League success, Ridsdale had got many

of the highest paid squad members to commit to long-term deals - again,

all paid for with the money secured on the Elland Road redevelopment.

To make matters worse, the fans were beginning to sense something was

up, especially after transfer rumours about a string of their biggest

stars - Mark Viduka, Danny Mills, Harry Kewell, Olivier Dacourt and Robbie

Keane - started appearing in the press with increasing frequency.

Behind the scenes, O'Leary was being told to sell. The gamble he had

bought into and initiated was not delivering. He had spent too much and

another season without Champions' League income was too much to bear.

Rio Ferdinand and Manchester United started being mentioned more and more

often in the same breath. Alex Ferguson had made no secret of his interest

in the player. Ridsdale saw the chance of making some cash.

O'Leary, however, was anxious not to break up a team he still felt was

capable of delivering the goods - in particular he wanted Ferdinand to

stay.

Ridsdale was at the point of no return. In June, while everyone was watching

the World Cup in Korea and Japan, Ridsdale sacked O'Leary. After four

years and close to £100m spent in the transfer market, Leeds' trophy cabinet

had not been opened once.

The terms of O'Leary's  settlement

would run into seven figures and rumble on for months to come. For now,

Ridsdale had to focus on hiring a new manager. A phone call to his Spanish

holiday resort pulled Terry Venables out of TV punditry and back into

management as Leeds confirmed him as O'Leary's successor just 11 days

later. He would become Leeds boss in an initial two-year deal. His first

mission was to talk to Bowyer who had put himself on the transfer list

following his trial and turned down a five-year deal. Venables also had

to persuade Ferdinand to stay. Said Venables at the time: 'This is a team

destined for greatness and maybe this season we will witness the O'Leary

Babes coming of age.'

settlement

would run into seven figures and rumble on for months to come. For now,

Ridsdale had to focus on hiring a new manager. A phone call to his Spanish

holiday resort pulled Terry Venables out of TV punditry and back into

management as Leeds confirmed him as O'Leary's successor just 11 days

later. He would become Leeds boss in an initial two-year deal. His first

mission was to talk to Bowyer who had put himself on the transfer list

following his trial and turned down a five-year deal. Venables also had

to persuade Ferdinand to stay. Said Venables at the time: 'This is a team

destined for greatness and maybe this season we will witness the O'Leary

Babes coming of age.'

Ridsdale was finding the balancing act of increasingly desperate chairman

and friend-of-the-fan more and more difficult to maintain. Despite peace

talks with Venables, Bowyer was committed to leaving - and was given permission

to discuss a £7m (rising to £9m on appearances) deal with Liverpool. As

for Ferdinand, Ridsdale publicly announced he was not for sale, a position

that was repeated in his first press conference as Leeds boss by Terry

Venables - while admitting that he would still have to raise £15m, a sum

he expected to bring in by off-loading the likes of Bowyer, Dacourt and

Keane. He added that he hoped 'sooner rather than later' he would be able

to start spending again.

Just two weeks later Ferdinand was sold for another record fee - this

time an astonishing £30m to Manchester United. It was a rare piece of

fantastic business for Leeds. 'I remain amazed that United paid that much

for Ferdinand,' says Bill Gerard. 'They must have known the situation

Leeds were in; they must have known they could have got him for less.

It was a great deal for Ridsdale.'

back to top

Gerard is convinced Leeds United would not have survived as long as they

have without that sale. Rivals they may be, but Manchester United's money

may have saved Leeds.

The required £15m was generated and Venables prepared for the new season.

The breakdown of talks for both Dacourt and Bowyer was suddenly not so

crucial, Venables believed. An August sale of Keane generated £7m - some

£5m less than Leeds paid.

Ridsdale, meanwhile, was preparing to man the emergency pumps while maintaining

that the club was waterproof. 'We set ourselves targets via a cash injection

and we have exceeded those targets, post these numbers, by selling Rio

Ferdinand and Robbie Keane,' he said in September 2002. 'There is therefore

no further requirement to reduce those players Terry Venables sees as

part of his ongoing first-team plans.'

But Leeds were about to have their cover blown.

That month Bill Gerard saw the figures for the financial year ending

30 June 2002 and started doing the sums. What he discovered frightened

the life out of him.

'I just could not believe what I saw,' he says. 'I looked at the balance

sheet and I looked at the cash flow, and I was astounded to work out that

just to make it to the end of the 2003 season would require £14m.'

The key headline figures Gerard focused on made sober reading: 'The figure

that was most frequently quoted in the media was net debt of £77.9m. This

represents the total borrowings net of the cash reserves. So what was

the problem? The bottom line was that the club's debt was not sustainable

given its operating losses. The year before, the club had a net operating

deficit of £5.7m before transfer expenditures and interest payment. Any

business that cannot generate operating surpluses to at least cover its

interest payments is in a very precarious position.'

Gerard took his findings to the City and showed them to the investors.

They immediately demanded a change in the board, telling him in November

2002 to consult with Allan Leighton to ensure the board acted quickly.

Though Gerard believed that Ridsdale was probably more responsible than

anyone for the mess, the majority of fans still trusted him, and just

weeks after the City was alerted to what was happening, Ridsdale was re-elected

to the board at the club's AGM with 96.7 percent of the shareholders'

votes.

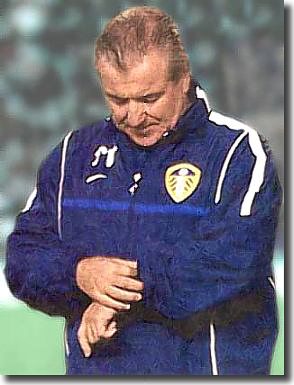

On the pitch the 2002/03 season had not

started well and by October pressure was beginning to build on Venables.

When in November Leeds were hit by two injury-time goals to have a 1-0

lead overturned by Sheffield United, thus ending their Worthington Cup campaign, the fans began to turn.

thus ending their Worthington Cup campaign, the fans began to turn.

Just over a week before the AGM, Ridsdale told Venables that a January

buying spree must be paid for by the sale of at least six players; the

club, he said, could not support a squad of 36 and the playing staff had

to be slashed to 30.

Days later, after losing at Spurs made it six defeats out of nine, Ridsdale

warned Venables results must improve or he must face the consequences.

And he had to do that with a squad including 11 players out injured and

whose big names were unsettled by transfer talk.

But Ridsdale's own power base was now threatened by shareholders insisting

a new chief executive was hired in the New Year.

With Bowyer leaving for just £100,000 to West Ham, and Robbie Fowler

to Manchester City for £3m in January 2003, Ridsdale was at pains to reassure

Venables that at least Woodgate, at the heart of the defence, was going

nowhere. Until, that is, Newcastle made a £9m bid, accepted at the end

of the month. Woodgate's departure was a hugely significant one. It publicly

undermined Venables, and publicly exposed not only the perilous state

of Leeds' finances but the quality of Ridsdale's stewardship.

back to top

'I didn't go public with my findings initially because Ridsdale still

had huge backing,' explains Gerard. 'By January nothing had changed and

the situation was getting worse so I finally made my concerns known after

the Jonathan Woodgate sale.'

It was at this time that Gerard received his letter from the plc warning

him not to suggest the Woodgate sale was a sign of a bigger problem. A

devoted fan, Gerard takes no pleasure in being proved right and still

bristles at the nerve of the club to pen him such a letter. 'It was absolutely

stupid. Because everything I was talking about was based on the publicly

released figures.'

Gerard carried on regardless and made it clear to the gathered audience

where he believed the blame lay: 'Ultimately there has been a governance

failure by which I mean a failure of accountability and transparency with

respect to key decisions. Control of the club and the company has been

vested in the senior executive management. We as fans are now having to

deal with the consequences of their actions. It is not a question of the

chairman's sincerity as a fan. We know he loves the club. But ultimately

he must accept responsibility for the business failures that have resulted

in the enforced sale of Woody. The business has been run honestly but

ultimately wrong decisions have been made.'

Behind

the scenes the board was responding to the shareholders' demands. A detailed

review of the organisation and structure of Leeds was completed: a managing

director was to be appointed, David Spencer was to leave the company with

immediate effect, and Professor John McKenzie, a non-executive director

with responsibility for pushing the Leeds brand into the Far East, was

to play a more hands-on role. Non-football costs were to be cut by £3

m a year.

Behind

the scenes the board was responding to the shareholders' demands. A detailed

review of the organisation and structure of Leeds was completed: a managing

director was to be appointed, David Spencer was to leave the company with

immediate effect, and Professor John McKenzie, a non-executive director

with responsibility for pushing the Leeds brand into the Far East, was

to play a more hands-on role. Non-football costs were to be cut by £3

m a year.

But by March, frustrated at being fed a line by Ridsdale and the board

and with a team failing to perform on the pitch, Venables quit just eight

months after taking over. Leeds were just eight points off the relegation

zone. Peter Reid was drafted in with the express purpose of avoiding relegation,

his success in this being rewarded by a permanent contract by the close

season. But the message was now clear. All the excited talk of new dawns

and Champions' League in the end amounted to this: avoiding relegation.

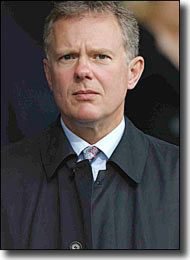

Ten days after Venables left, Peter Ridsdale bowed to the inevitable

and quit as chairman. With the fans now aware he was at least in part

responsible for gambling with their future, he had few allies. 'Ridsdale

had gambled the house, but it wasn't his to gamble,' says Gerard. 'The

Leeds fans trusted him. When they realised what he had done, it fuelled

their hatred towards him.'

Ridsdale blamed others for forcing him out and turning him into a non-executive

director. And he turned on the fans: 'In a high-profile role, when results

are not up to expectation levels, you rightly expect criticism. This comes

with the territory. But when this becomes so intense that it affects your

family and health it requires clear reflection on the right way forward.

The intensity of personal criticism has led me to conclude that the best

decision for myself, my family and the company is that I step down as

chairman of the plc and football club and relinquish all executive responsibilities.

This I am doing.

'The ongoing challenge will continue to be to get the cost base into

line with anticipated revenue streams. Further action will be needed in

the coming months to achieve this.'

Weeks later Stephen Harrison quit too. The Ridsdale power base, it seemed,

was finally at an end.

One of the new chairman John McKenzie's first major moves was to reveal

publicly the extravagant spending which had led to their mounting losses.

The interim finance figures for the second half of 2002 showed the club

lost £17.2m before tax, while the total net debt to the end of the year

was £78.9m. Among the headline-grabbing details were:

- 5.7m in compensation pay-outs to former managers O'Leary and Venables

- £70,000 for private jets for directors and senior management - in

one year alone

- £500,000 a year on the wages of former striker Robbie Fowler - despite

his sale to Manchester City

- £20 a month on goldfish for Peter Ridsdale's office

Yes, even Ridsdale's pets enjoyed the high life at Leeds.

McKenzie described the scale of the operation as 'like an oil tanker

heading straight for the rocks and now the shareholders have put someone

else on board to turn it around'. To help cut costs, McKenzie made a mass

of redundancies. A new chief financial officer, Neil Robson, from accountancy

giants Ernst & Young was brought in. The mission now was simple: survival.

Back on the pitch, Peter Reid was not having the best of times either.

As the set-up of the club collapsed around him, he had a huge falling

out with striker Mark Viduka, who had played such a crucial role in keeping

the club from relegation the season before. By November, and following

a 6-1 thrashing by newly promoted Portsmouth, Reid had his name added

to the 'managers requiring compensation' list. Loyal servant Eddie Gray

was drafted back in as manager. The previous month, Leeds United made

what many believe to be their best signing throughout the whole sorry

affair.

Having been instrumental in bringing Roman Abramovich to Chelsea, former

Liverpool player Trevor Birch was brought in as chief executive officer.

He would run the day-to-day business while McKenzie would concentrate

on the strategic development of the club, working part-time as a non-executive

chairman with new financial chief Neil Robson on refinancing and restructuring.

With his good relationship with the City, Trevor Birch was immediately

able to open negotiations to try to give Leeds more breathing space.

'Thank God we got Trevor Birch,' says Gerard. 'He knows what he is doing

and is working for the good of the club. If anyone can get us out of this

situation then Birch can.'

But it's a very big if. For the year ending 30 June 2003, Leeds made

pre-tax losses of £49.5m, while debts remained at £78m. The club was at

least buoyed by a £4.4m cash injection split between Allan Leighton and

the ARM Holdings Group.

By December the newspapers were full of stories about possible takeovers

of the club. In particular speculation was rife that a member of the Bahrain

royal family was considering a bid.

back to top

By the end of December, McKenzie announced he would not seek re-election

to the board, heightening belief he could be about to mount his own bid.

Without at least £5m the club would not survive until the end of the

season. Creditors began closing in and a number of deadlines were put

in place to avoid the club being forced into administration.

As we go to press, the story is not over, nor may it have a happy ending.

So who is the villain of the piece?

'As chairman you have to take responsibility,' says Peter Ridsdale, now

chairman of Leeds' neighbours Barnsley. 'I was the representative of the

board and have  to

take the rap for it. But what upsets me is that it is assumed every decision,

every spending decision, was taken by me on some personal crusade or emotional

whim, which is simply not the case. Every decision to buy or sell a player

was taken after consultation with every board member. Only with approval

did we proceed.'

to

take the rap for it. But what upsets me is that it is assumed every decision,

every spending decision, was taken by me on some personal crusade or emotional

whim, which is simply not the case. Every decision to buy or sell a player

was taken after consultation with every board member. Only with approval

did we proceed.'

The £60m gamble

When Caspian took over Leeds United they were partially attracted by

the redevelopment potential of the Elland Road site. Their vision included

a hotel, indoor hockey arena, exhibition centre and a range of other leisure

facilities. All the revenues would drive monies back into the club and

provide long-term security for the group.

As the original Caspian management team left, Peter Ridsdale took over

the reins of the project. By 2001 he had changed the plan from refurbishing

Elland Road to moving to a new site altogether and building a state-of-the-art

50,000-capacity stadium on the outskirts of the city.

Ridsdale's plan was simple. To finance the new stadium Leeds United would

sell Elland Road for £20m. It would then find a naming rights sponsor

for the new venue who would secure a long-term deal for £40m.

The club would then secure a loan for £60m - with funds coming from a

bond secured against future season ticket and corporate hospitality sales

- with which to invest in the squad. The securitisation deal would see

banks lending Leeds the money over 25 years, with repayments accruing

from ticket and hospitality package sales.

The benefit of this type of financing for the borrower is that the rates

are low, and the risks for the lender are reduced as existing or forecast

revenue streams are utilised and channelled to repay the loan.

It was fundamentally a good business move. It meant an injection of funds

to help them push towards constant Champions' League qualification, while

allowing the club to develop value bricks and mortar assets in terms of

the new development. After putting the £60m proposal to shareholders,

Ridsdale won support to push ahead with his plans. The group issuing the

bond include M&G, MetLife, Teachers and Gerling.

Crucially, however, Ridsdale and the board believed they could sell the

all-important naming rights to the stadium themselves, rather than recruiting

a specialist agency. They failed, blaming the economy post-9/11, but a

more likely cause is the bad publicity surrounding the Woodgate/Bowyer

case.

But at some point during 2002, the board quietly dropped plans for the

new venue. With no new stadium, there are no new revenue streams. Nor

did Elland Road ever become the entertainment centre of Leeds. So with

no revenues to repay the debt, the future of the club now rests with its

major creditors, the fund managers of the bond.

'The bond issue, you must remember, was agreed by our shareholders,'

says Allan Leighton. 'But the point is that in hindsight we can see it

did not work. The issue now is to deal with the future.'

That's assuming, of course, that Leeds United has a future.

The Four Four Two feature emerged at a key point in the story

of United's financial crisis, as the very future of the club hung in the

balance. Eventually, administration was avoided, but only after one of

the most fraught periods in Leeds United's entire history.

back to top

Part 1 A season from Hell - Part

3 - Back from the brink - Part 4 End of

an era - Results and table

Though

Graham transformed a leaky defence, his team closed up at the other end,

too, scoring just 28 goals in 38 league games and ending in 11th place.

The fans, sensing this cautious approach was worth their patience, remained

positive.

Though

Graham transformed a leaky defence, his team closed up at the other end,

too, scoring just 28 goals in 38 league games and ending in 11th place.

The fans, sensing this cautious approach was worth their patience, remained

positive. On

the pitch, meanwhile, the 1998-99 season was disrupted early by the departure

of George Graham back to north London with Spurs. As assistant to Graham,

David O'Leary had shown promise after assuming the caretaker-manager position

and he was offered a full-time contract with Eddie Gray as his assistant.

Unlike Graham, O'Leary was not afraid to introduce young blood to the

Leeds team. At his disposal were the likes of Lee Bowyer, Harry Kewell,

Alan Smith, Ian Harte and Jonathan Woodgate as a balance to experienced

squad members such as David Batty, Lucas Radebe and Gary Kelly. For the

plc, the double-edged bonus was that the young talent would eventually

either deliver riches on the pitch or profits off it courtesy of the still

booming transfer market. Ideally both.

On

the pitch, meanwhile, the 1998-99 season was disrupted early by the departure

of George Graham back to north London with Spurs. As assistant to Graham,

David O'Leary had shown promise after assuming the caretaker-manager position

and he was offered a full-time contract with Eddie Gray as his assistant.

Unlike Graham, O'Leary was not afraid to introduce young blood to the

Leeds team. At his disposal were the likes of Lee Bowyer, Harry Kewell,

Alan Smith, Ian Harte and Jonathan Woodgate as a balance to experienced

squad members such as David Batty, Lucas Radebe and Gary Kelly. For the

plc, the double-edged bonus was that the young talent would eventually

either deliver riches on the pitch or profits off it courtesy of the still

booming transfer market. Ideally both. It

is believed that Fenn, shy of the limelight and more content with simply

handling the behind-the-scenes business operation, was made to feel particularly

uncomfortable when O'Leary stated publicly that some of his moves for

certain players were being stifled by elements on the board. Fenn, who

remains proud of his reputation as a tough negotiator and book balancer,

was to become the first victim of what many saw as Ridsdale's move to

have more control of the club. He quit to reunite with Akers on his Sports

Internet Group.

It

is believed that Fenn, shy of the limelight and more content with simply

handling the behind-the-scenes business operation, was made to feel particularly

uncomfortable when O'Leary stated publicly that some of his moves for

certain players were being stifled by elements on the board. Fenn, who

remains proud of his reputation as a tough negotiator and book balancer,

was to become the first victim of what many saw as Ridsdale's move to

have more control of the club. He quit to reunite with Akers on his Sports

Internet Group. chairman

at Hull City, he is convinced this period was crucial in Leeds' financial

downfall: 'It was a change of culture. Obviously I had been appointed

by Jeremy Fenn as commercial director at the football club and we had

built the club up on basic business premises which were to build the business

and keep the costs low. And obviously that culture changed considerably

over the coming years. I think we had just about maximised the turnover.

But then I could see the costs started to creep up and, after Jeremy's

departure, the way the club was run changed.'

chairman

at Hull City, he is convinced this period was crucial in Leeds' financial

downfall: 'It was a change of culture. Obviously I had been appointed

by Jeremy Fenn as commercial director at the football club and we had

built the club up on basic business premises which were to build the business

and keep the costs low. And obviously that culture changed considerably

over the coming years. I think we had just about maximised the turnover.

But then I could see the costs started to creep up and, after Jeremy's

departure, the way the club was run changed.' into

account the big buying, Leeds United plc - it had switched from its Leeds

Sporting name during the summer - posted a £7.59m loss against a £1.24m

pre-tax profit.

into

account the big buying, Leeds United plc - it had switched from its Leeds

Sporting name during the summer - posted a £7.59m loss against a £1.24m

pre-tax profit. the

Bowyer/Woodgate trial. With one trial already called off after a Sunday

newspaper was guilty of contempt of court, it was not until December that

the jury got to make a decision - close to two years after the incident

involved. Ridsdale had decided to stick by the players until a verdict.

While Bowyer was cleared at Hull Crown Court of causing grievous bodily

harm with intent and affray, Woodgate was given 100 hours of community

service after being found guilty of affray. Their friend Paul Clifford

received six years for GBH. Evidence during the case painted a less than

pretty picture of both players.

the

Bowyer/Woodgate trial. With one trial already called off after a Sunday

newspaper was guilty of contempt of court, it was not until December that

the jury got to make a decision - close to two years after the incident

involved. Ridsdale had decided to stick by the players until a verdict.

While Bowyer was cleared at Hull Crown Court of causing grievous bodily

harm with intent and affray, Woodgate was given 100 hours of community

service after being found guilty of affray. Their friend Paul Clifford

received six years for GBH. Evidence during the case painted a less than

pretty picture of both players. settlement

would run into seven figures and rumble on for months to come. For now,

Ridsdale had to focus on hiring a new manager. A phone call to his Spanish

holiday resort pulled Terry Venables out of TV punditry and back into

management as Leeds confirmed him as O'Leary's successor just 11 days

later. He would become Leeds boss in an initial two-year deal. His first

mission was to talk to Bowyer who had put himself on the transfer list

following his trial and turned down a five-year deal. Venables also had

to persuade Ferdinand to stay. Said Venables at the time: 'This is a team

destined for greatness and maybe this season we will witness the O'Leary

Babes coming of age.'

settlement

would run into seven figures and rumble on for months to come. For now,

Ridsdale had to focus on hiring a new manager. A phone call to his Spanish

holiday resort pulled Terry Venables out of TV punditry and back into

management as Leeds confirmed him as O'Leary's successor just 11 days

later. He would become Leeds boss in an initial two-year deal. His first

mission was to talk to Bowyer who had put himself on the transfer list

following his trial and turned down a five-year deal. Venables also had

to persuade Ferdinand to stay. Said Venables at the time: 'This is a team

destined for greatness and maybe this season we will witness the O'Leary

Babes coming of age.' thus ending their Worthington Cup campaign, the fans began to turn.

thus ending their Worthington Cup campaign, the fans began to turn. Behind

the scenes the board was responding to the shareholders' demands. A detailed

review of the organisation and structure of Leeds was completed: a managing

director was to be appointed, David Spencer was to leave the company with

immediate effect, and Professor John McKenzie, a non-executive director

with responsibility for pushing the Leeds brand into the Far East, was

to play a more hands-on role. Non-football costs were to be cut by £3

m a year.

Behind

the scenes the board was responding to the shareholders' demands. A detailed

review of the organisation and structure of Leeds was completed: a managing

director was to be appointed, David Spencer was to leave the company with

immediate effect, and Professor John McKenzie, a non-executive director

with responsibility for pushing the Leeds brand into the Far East, was

to play a more hands-on role. Non-football costs were to be cut by £3

m a year. to

take the rap for it. But what upsets me is that it is assumed every decision,

every spending decision, was taken by me on some personal crusade or emotional

whim, which is simply not the case. Every decision to buy or sell a player

was taken after consultation with every board member. Only with approval

did we proceed.'

to

take the rap for it. But what upsets me is that it is assumed every decision,

every spending decision, was taken by me on some personal crusade or emotional

whim, which is simply not the case. Every decision to buy or sell a player

was taken after consultation with every board member. Only with approval

did we proceed.'