Part 1 - Off like a train - Part

3 - Colchester, Tinkler and Fairs success - Results

and table

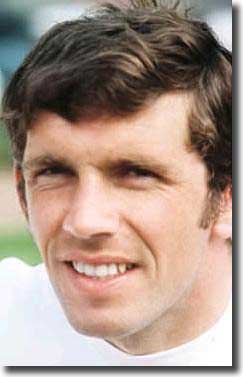

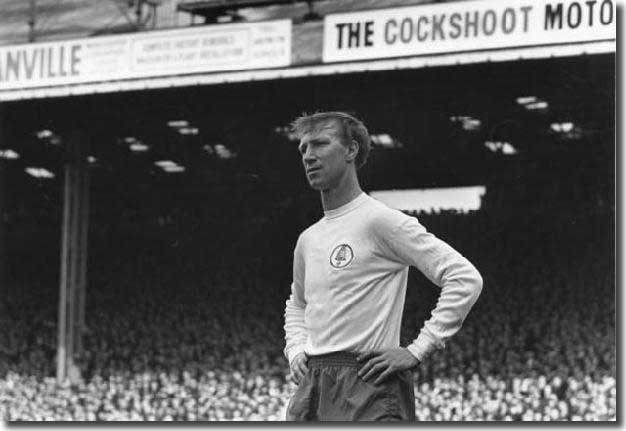

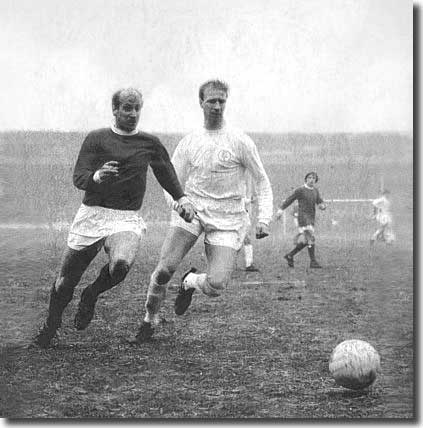

In October 1970, Leeds

United centre-half and senior professional Jack Charlton was involved

in one of the year's great sporting controversies. He had agreed to be

interviewed by broadcaster Fred Dinenage for Tyne Tees Television on Saturday,

3 October. The interview was arranged as part of a pilot programme but

was considered so good that it went out unedited, with Charlton's agreement.

The defender was in high spirits after United's impressive

start to the season. Leeds had beaten Huddersfield earlier in the day

and earlier in the week he had scored twice in a 5-0 defeat of the Norwegians,

Sarpsborg. Much of the interview was a light hearted affair with Jack

playing up to the cameras and the audience, and, according to Geoffrey

Green in The Times, 'Charlton himself emerges as the man he is,

warm, forthright, articulate and honest.'

The following verbatim extracts were the elements that sparked

the controversy.

Question: As wages and incentives have got higher, has the

game got more violent?

Answer: You do what is necessary in the circumstances. That

is one of Alf Ramsey's great sayings. If I was playing in an international

and saw someone getting away with the ball and I could not catch him,

I would flatten him. My job is to stop a man scoring. I would not break

anyone's leg or anything like that, but I would maybe grab him by the

scruff of the neck and stop him running. I think every defender in the

Football League would do it.

Question: You have had your fair share of cuts and bruises.

What is the worst thing that has happened to you, what is the worst foul?

Answer: I cannot mention names but I have a little book

with two names in it and if I get the chance to do them I will. I do not

do what I consider to be the bad fouls in the game such as going over

the top. That is about the worst foul in the game, but I will tackle as

hard as I can to win the ball, but I will not do the dirty things, the

really nasty things. When people do it to me I do it back to them. Because

I am not noted for doing so people don't do it to me, but there are two

or three people who have done it to me and I will make them suffer before

I pack this game up.

Charlton declined to confirm exactly who was on his hit

list, but promised ominously 'they know who they are.'

The programme was originally screened only in the Tyne Tees

region, but like wildfire, quotes spread like wildfire in the media all

over the country, with Charlton painted as the blackest of wrongdoers.

The interview was given a nationwide screening when it was repeated in

full on ITV's World of Sport the following Saturday, 10 October.

Forty years on, it all seems something of a trivial matter.

At the time, however, what became rather po-facedly known as 'The Charlton

Affair' was taken very seriously indeed by the self righteous guardians

of the game's good name.

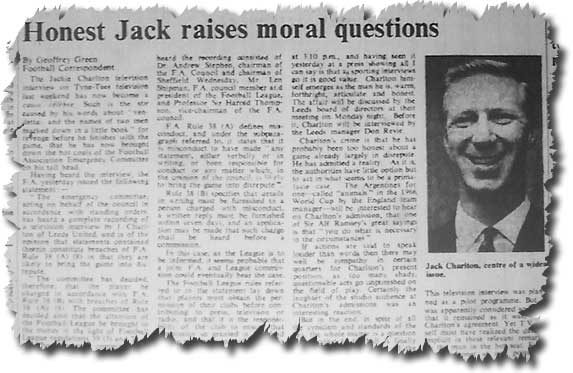

The Football Association announced that they would take

immediate steps to investigate the matter, a spokesman saying, 'The matter

is already receiving attention and early contact will be made with Charlton

through his club. If he admits making the remarks reported, it will be

taken up to the Emergency Committee to decide whether he will have to

face a charge of bringing the game into disrepute.'

Don Warters reported in the Yorkshire Evening Post:

'The man who was England's World Cup centre-half in 1966 has a reputation

throughout the game as a gentlemanly character on the field, hard enough,

yet fair enough, but for those who know him off the field he is a man

who will speak his mind without fear or favour. I have a great respect

for anyone who speaks his mind, but there are times when it is better

to bite the tongue.

back to top

'Jack Charlton is the elder statesman of the Leeds United

side, but his remarks ... were hardly diplomatic. They may have been true

... but they have not done the image of football both in this country

and abroad the slightest bit of good.

'Charlton has played the game a long time, and while he

would be the last person to want to wrongly influence youngsters taking

up the game, his outburst will not have gone unnoticed by boys who look

upon such as Charlton as idols and also for guidance.

'Jack Charlton may only have said publicly what other players

will admit privately - that vendettas in top soccer do go on - but this

surely was an instance where Big Jack should have fallen into line and

kept his thoughts and his intentions to himself.'

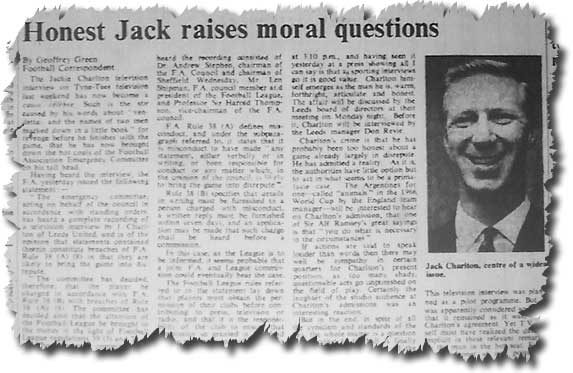

By the end of the week, the FA had charged Charlton with

having made remarks likely to bring the game into disrepute, issuing a

statement which read: 'The Emergency Committee, acting on behalf of the

council in accordance with standing orders, has heard a complete recording

of a television interview by Jack Charlton, and is of the opinion that

statements contained therein constitute breaches of FA Rule 38 (A) (8)

in that they are likely to bring the game into disrepute. The committee

is decided, therefore, that the player be charged in accordance with FA

Rule 38 (8) with breaches of Rule 38 (A) (8).  The

Committee has decided also that the attention of the Football League be

brought to the matter in the light of Football league regulations 39 (3)

and 74. The Emergency Committee has further decided that until the matter

has been resolved the England team manager should be informed that Charlton

won't be eligible for selection for any FA representative teams.'

The

Committee has decided also that the attention of the Football League be

brought to the matter in the light of Football league regulations 39 (3)

and 74. The Emergency Committee has further decided that until the matter

has been resolved the England team manager should be informed that Charlton

won't be eligible for selection for any FA representative teams.'

That last part effectively ended Charlton's England career,

although, at 35 and with Alf Ramsey intent on rebuilding for 1974, he

was no longer in contention anyway.

Charlton was roundly booed by the home supporters when playing

at West Bromwich Albion on 10 October, though he said at the time: 'I

must thank the supporters of West Brom ... for the wonderful way they

treated me. It was the most nerve-wracking game of my life, which covers

a lot of ground, but I was allowed to settle into it without trouble.

They treated me strictly on merit during the game.'

The FA's investigation took almost a month to complete.

On 4 December, The Times reported the outcome: 'Jackie Charlton,

of Leeds United and England, has been admonished by the Football Association

after his black book interview on television last October when he said

that he would do two players whose names he had in a book if he had the

chance. A three-man commission in London yesterday also advised him to

be more careful in future when commenting on the game.

'A statement, made by the FA secretary, Denis Follows, said

that Charlton expressed regret that anything he said could have been construed

in such a way as to bring the game into disrepute. He felt that certain

remarks he made might have been better expressed.

'The commission accepted that Charlton had been speaking

in a light hearted manner for a television audience; also that he might

not have realised the serious effect which his statement would have on

the public, or that the reaction was likely to bring the game into disrepute.

The commission decided that because of his length of service in football

and his established position as a senior player and an international,

certain remarks were ill considered.'

Charlton devoted his Saturday column for the Yorkshire

Evening Post a couple of days later to the matter. 'When I asked the

FA for complete privacy at my hearing, the last thing I expected was that

it would be effective. The whole little black book affair, as it had become

known, had been about as private as a goldfish bowl.

'For two weeks people were calling at my home and on my

telephone. There was hardly a minute free from it wherever I went. Yet

at the hearing there were no reporters, no photographers, no television

cameramen, nobody from the film companies. The ironic thing was that of

all places to have the meeting, it took place in the London offices of

Tyne Tees Television!

'The reason for having it there was that the commission

had agreed to see the television interview all the fuss was about before

passing judgement.

'The reaction next day was in complete contrast to all this

hullabaloo. I would have thought the people who knocked me would at least

have had the decency to complain about me getting off with such a mild

caution. Most of them seemed conveniently to have forgotten about it all.

Maybe the truth is they were all a bit shame faced.

'People I have known for years kept on at me while the name

Jack Charlton was being criticised and generally mauled about. They wanted

me to justify what I had said on television but I refused to discuss it

with anyone who had not seen it for themselves. I kept telling them the

words, taken out of context and out of the atmosphere in which they were

said, gave the wrong impression. Those who did go away to see it never

came back on the subject and that surely  was

the most significant thing.

was

the most significant thing.

'More than 400 people wrote to me. Most of those who were

with me had seen it and wanted to say how much they enjoyed it. There

were six letters against me, but only one of the half dozen writers had

seen what he was writing about. It was a bit of an effort but I wrote

back to them all, personally.

back to top

'Looking back ... I now realise I was wrong to say the things

I said, the way I said them. It's not because of the fact that Jack Charlton

was hurt. That's nothing. But it gave people the opportunity to hurt through

me the game I love. I regret that very much.

'The truth is there was never any little black book. It

was just my way of saying there are a couple of players who have had an

unfair go at me at one time or another.

'People criticised me for saying too much. The trouble I

feel now is that I didn't say enough. I thought I had qualified all I

had said so there could be no misunderstanding. Obviously I was wrong.

'If I was hurt it doesn't show now. Apparently people don't

dislike me as much as they did. At any rate I have never been better received

to my face. Maybe they say other things behind my back, but I'll never

know about that.

'The darkest part was the ignominious end to my international

career. I knew it was over anyway. It was logical if, as I said the other

day, you look at the England team in a way that makes the distant future

all important. But after 35 caps, goodness knows how many representative

matches, as well as months spent training with the England lads, to be

evicted in that way...

'Now, they say I am available again for selection by England.

I know I won't be picked again, but just to be free to be chosen again

is a great thrill!

'I apologised to the FA Commission. I told them any offence

I had caused was wholly unintentional. The interview was recorded. I could

have dropped it or any part of it, but it never occurred to me it would

be wrongly construed.

'What this has taught me is to pick my friends with a little

more care, and not to say things in a way that they might be misunderstood.

I was lucky. It was something I needed to learn at this stage of my career.

There are going to be times when I have to say things that are in my mind,

but I'll take greater care to make sure I put them in the right way.'

Leo McKinstry in Jack & Bobby - A story of brothers in

conflict: 'It was Jack's almost brazen honesty that was to land him

in the greatest controversy of his career. In October 1970, Tyne Tees

Television conducted an in-depth interview with him about the realities

of life as a top professional footballer. It was a far more thorough,

interesting job than most of the dreary, cliche-ridden, 'boys-done-good'

interviews that are served up today for public consumption. The first

reaction to the programme was highly positive. In the Tyne Tees building,

the studio audience watching the live filming of Charlton's performance

laughed and applauded. Amongst their number were Cissie and Bob Charlton,

who rose to his feet with pride and declared his brother to be a man's

man.

'As usual with such sagas, it was not the interview itself

which provoked the outrage, but the interpretation of it in the press.

Several reporters, attending the Tyne Tees preview, picked up Jack's remarks

and relayed them to their national offices. The moment they appeared in

print, there was a national outcry. Macaulay famously wrote in 1843 that

there is "no spectacle so ridiculous as the British public in one of its periodical fits of morality"

and it was exactly one such fit which now had Jack Charlton at its centre.

"These sickening comments," ran the headline in the Daily

Express, above an opinion piece by sports editor John Morgan which

called for Charlton to be sacked by Leeds: "The damage caused by

the words Charlton used cannot be estimated in the effect it will have

on hundreds of youngsters. The damage abroad will show in the inevitable

repercussions years hence." In the Daily Mirror Peter Wilson

asked: "Have these petulant, primping, over-paid, under-principled

gladiators no responsibility?"

ridiculous as the British public in one of its periodical fits of morality"

and it was exactly one such fit which now had Jack Charlton at its centre.

"These sickening comments," ran the headline in the Daily

Express, above an opinion piece by sports editor John Morgan which

called for Charlton to be sacked by Leeds: "The damage caused by

the words Charlton used cannot be estimated in the effect it will have

on hundreds of youngsters. The damage abroad will show in the inevitable

repercussions years hence." In the Daily Mirror Peter Wilson

asked: "Have these petulant, primping, over-paid, under-principled

gladiators no responsibility?"

'As he had always done on the football field, Jack displayed

remarkable calm under pressure. He refused to retract any of his comments

and rightly said he was only speaking the truth about what went on in

professional football. He told the Yorkshire Evening Post on 5

October, "I have no regrets. I stand by what I said during the interview.

I have been in this game a long time and I am not a dirty player, but

what I referred to in the interview does happen. Everyone knows what goes

on but no-one has ever said it before. I was asked a question and I answered

it honestly." What particularly annoyed him was the way the journalists

rushed to condemn him without actually having viewed the film. "The

press have knocked me terribly about something they know nothing about.

It has been taken completely out of context. Everything I said was qualified."

With the loyalty that was his hallmark, manager Don

Revie supported him. Having viewed the film, he said he could not

see what all the fuss was about.

back to top

'Other, less feverish voices in the media put the row into

some context. Ian Wooldridge in the Daily Mail praised Jack for

breaking "a conspiracy of silence" over vendettas in professional

sport. "Vendettas did not start with Jack Charlton. They are as old

as Dixie Dean." Wooldridge then recounted the story of how the 16-year-old

Dean had lost a testicle to a particularly vicious defender while playing

for Tranmere. Dean had told Wooldridge, "17 years later, I saw him

in a pub in Chester. I waited for him to leave, followed him down the

road and then, in a quiet corner I beat the living daylights out of him."

Joe Mercer, the hugely respected manager of Manchester City, put forward

the widely held view in the football world that Jack was not a dirty player:

"He is no soccer hard man. He's a good professional. He's a sportsman

who loves to win. But he is not an assassin on the field who must win

at all costs. I can tell you straight that none of my Manchester City

players have any fear of Charlton." For the Professional Footballers

Association, Derek Dougan gave this balanced verdict: "I have played

against Jack at club and international level and have found him a very

fair competitor. I wouldn't say he wasn't hard, but I don't think I have

ever had any sort of injury when playing against him. He may be justified

in saying this because in the past one or two players may have taken liberties

against him."

'Football's administrators, however, felt they had to respond

to the public mood and immediately imposed a temporary ban on Jack playing

for England, a meaningless punishment given that Jack had told Ramsey

on the plane back from Mexico that he wished to retire from international

football. A special joint disciplinary committee was then organised by

the Football League and FA to hear the charge against Jack of bringing

the game into disrepute. Ably supported by Revie, Jack persuasively argued

his case and was, effectively, exonerated. There was to be no suspension

or fine, and Jack was only required to make an apology for his remarks.

This he did in the most adroit way, managing a not-too-subtle dig at the

media: "I apologise that, through me, the press were given an opportunity

to knock football."

'It was ironic that Jack Charlton should be the focus of

such a controversy over dirty play, given that ... there were many in

his own Leeds side who were far more guilty. Indeed, Jack strongly opposed

the cynical, sour professionalism of the Leeds approach as John Giles,

confirmed to me. "Jack would get stuck in, do his job and do it well,

but that was it. Bobby Collins,

for instance, was a great player, but he was also very aggressive and

Jack didn't like that. Now in the Sixties, football was a violent game.

If you were a skillful player, other teams would try to put you out of

the match. If you didn't give it back, you were a soft touch. My attitude

was that I had to respond in order to play. So I responded, Bobby Collins

responded and it could be very vicious. Jack knew what I was doing, and

he never approved of that. So we had a few rows about it."

'Alan Gowling, who played as a striker for Manchester United

from 1968 before he joined Newcastle, gave me this perspective on facing

Jack: "I personally always found him very fair. He was physically

very strong, dominant in the air, tough to play against but he was not

dirty. He could handle himself but he would not resort to the kind of

off-the-ball tactics that a lot of Leeds players went for. I can always

remember one occasion when we were at Elland Road. Jack had got the ball

with his back to me. I tried to get past him and caught him on the leg.

He turned round as if he was going to throw this great punch at me. And

then he saw it was me and realised I was not someone who would normally

kick him just for the sake of it. He said, 'It's a good job it was you.'"

'The hypocrisy of the game in 1970 was that both officials

and journalists whipped up a frenzy over Jack while doing little about

far worse offenders. The idea that Jack was some sort of thug, working

his way through a hit list, was just absurd, as John Giles says: "The

black book was just a joke in the Leeds dressing room. But Jack got in

trouble because he never saw anything wrong in speaking his mind."

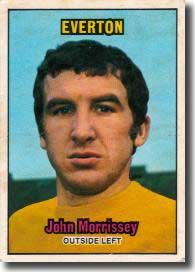

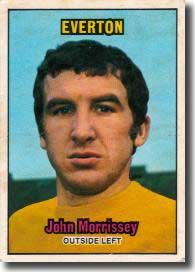

'Later, Jack revealed the names of several of the players

he particularly despised - Bertie Auld of Celtic, George Kirby of Southampton

("a player always liable to hurt you") and John Morrissey, the

Everton winger. Brian Labone, Morrissey's Everton colleague, understands

why Jack felt strongly about him: "John was a dirty little bugger.

He was about half the size of Jack and when he was around, you had to

look out."

'Perhaps the most interesting aspect of this whole sorry

business was the way it provided the first glimpse into the tensions within

the Charlton family. Despite their distance, both the brothers had always

been loyal to each other in their public pronouncements, but on this occasion,

Bobby - who, coincidentally played his 500th game for United during the

week of the broadcast - decided to go on the attack. In an article on

7 October 1970 in the Daily Express, under the headline "Explain

Yourself Brother Jack," Bobby said: "The remarks on the record

would not come well from a lad of 20 or 21 who had been in the game five

minutes. But the effect is that much worse when they come from someone

of Jack's experience and prestige. Jack must know what effect this business

is having, that it is not doing the game any good. But he appears to be

sticking to his guns. This is Jack all right. He is as stubborn as they

come.' The New Zealand journalist  Norman

Harris was in Jack's house at the time of the crisis and, in a diary piece,

described the reaction to Bobby's article: 'There is now some dissension

in the family, and unpleasantness in a phone conversation between the

two brothers." Then Cissie took up the cudgels against Bobby, no

longer the favourite son since his marriage to Norma: "I am amazed

at our Bobby," she told the Daily Mail, "he's in the

same position as all of Jack's other critics. He hasn't seen the television

programme." And she added, in defence of Jack, "Everyone knows

Jack is not a dirty player. Where has everyone's sense of humour gone?"

Norman

Harris was in Jack's house at the time of the crisis and, in a diary piece,

described the reaction to Bobby's article: 'There is now some dissension

in the family, and unpleasantness in a phone conversation between the

two brothers." Then Cissie took up the cudgels against Bobby, no

longer the favourite son since his marriage to Norma: "I am amazed

at our Bobby," she told the Daily Mail, "he's in the

same position as all of Jack's other critics. He hasn't seen the television

programme." And she added, in defence of Jack, "Everyone knows

Jack is not a dirty player. Where has everyone's sense of humour gone?"

'As with so many press-inspired squalls, this one disappeared

almost as soon as it had blown up. The lurid predictions of a collapse

in the standing of the game never materialised. Nor was there any real

long-term damage to Jack's reputation. Indeed, if anything, he was respected

all the more for his plain speaking in the twilight of his career.

'Jack's tough physical approach was seen by many as the

embodiment of the worst of Leeds' aggressive footballing culture. Jack

was once speaking at a dinner in Newcastle, alongside the film director

Colin Welland. As Welland started his speech, he picked up a mysterious

heavy object, wrapped in newspaper, and took it over to Jack. He handed

this strange parcel to Jack with the words: "There you are, Jack.

There's something you always wanted."

back to top

'Jack, looking puzzled, opened it up and there was a bone

covered with blood and some remains of meat.

'"Colin, what the hell's this?" asked Jack.

'"Derek Dougan's shin bone," joked Welland, to uproarious

laughter. But that was the way much of the public thought of Jack.

'To be fair to Jack, he was a robust player but never a

dirty one. His offences, like his shirt-ripping against Denis Law, were

all too obvious and usually reflected an intemperate spirit. But he was

incapable of the sort of insidious, cynical challenge that characterised

other members of the Revie side. Ian St John says he never had "that

nastiness, that villainous outlook", while Peter Lorimer told me

that Jack "hated the dirty players, the guys who went over the top.

He would fight and compete for every ball but he never believed in tackles

that could break someone's leg. He had his rules about how the game should

be played."

'For all his dislike of nasty play, he was not averse to

ignoring the law. Ian Storey-Moore, once of Forest and Manchester United,

says, "He was an awkward bugger to play against, to be honest. If

you got past him, then you would pretty quickly feel the tug of the shirt.

I don't think he was too averse to bringing you down. I think he would

have many more bookings if he had been playing today." Jack was regularly

at the centre of trouble because of his short fuse. "I have always

been terribly fond of Jack," says Brian Glanville. "But  there

is a violence within him." Again, Storey-Moore argues that, though

"Jack was not the worst of the Leeds, team, he did have a violent

temper. If someone upset him in a game, I think he would certainly make

sure he left his mark on that player."

there

is a violence within him." Again, Storey-Moore argues that, though

"Jack was not the worst of the Leeds, team, he did have a violent

temper. If someone upset him in a game, I think he would certainly make

sure he left his mark on that player."

'In a European Fairs Cup-tie against Valencia at Elland

Road in the 1965/66 season, he went so berserk that the intervention of

the Yorkshire constabulary was required. Jack recalls that after one corner,

he was kicked on the ankle by the Valencia left-back. "I looked across

at him. He started to run away round behind the goal. I went after him.

Next thing I was surrounded by Valencia players. The full-back stood behind

them, cowering for protection. I had more or less calmed down when, right

from the back, their goalkeeper leaned through and punched me straight

on the mouth. As I wiped the blood away, the players opened up and I could

see the keeper a few yards away. I went running after him but a policeman

threw himself on top of me, driving his knee into my thigh." Not

surprisingly Jack and the full-back were sent off, while the goalkeeper,

terrified of the wrath of Jack, had jumped over the fence and hidden amongst

the spectators. At a subsequent FA hearing the referee, Leo Horn from

Holland, said that he has never seen such madness as was in Jack's eyes

that night. As Peter Lorimer puts it, "That Valencia game showed

Jack's temper. The keeper had a choice, jumping into the crowd or facing

Jack. He chose the crowd. I would have done the same." Jack was subsequently

fined £50 with £30 costs.'

Jack Charlton in his autobiography: 'I felt the interview

went well, and they seemed quite pleased with it at the time. It was just

about football, about the realities of the game. I mentioned that if a

player did something nasty or unnecessary to me, I wouldn't forget it.

His name would go down in my black book. If the chance of retaliation

came, I'd tackle him as hard as I could. I'd kick him five yards over

the touchline if I had the opportunity. But I'd do it within the laws

of the game, when the ball was there to be played.

'Note that phrase "within the laws of the game".

I didn't say I'd deliberately kick the guy in the air in any circumstance.

What I did say was that if the opportunity presented itself, I'd pay him

back, in a hard but perfectly legitimate tackle. You can be as hard as

you like in the game of football. There is no rule to say you cannot tackle

as hard as you want - but within the laws of the game, when the ball is

there to be played.

'The purpose of the remark was not to shout my mouth off

about what a hard man I was. I was merely explaining some of the professional

practices prevalent in the game at the time ... But then this local reporter

in the Newcastle area is invited to a preview of the programme, takes

my remarks out of context, and puts a lot of quotes on the wire to all

the news agencies in London - things like "Jack Charlton says he

would kick a player five yards over the touchline", "Jack Charlton

says he has got a black book with names in it of players he will get before

he finishes his career" - quotes like that. Suddenly the tabloids

are running stories with headlines like "Kick Jack Charlton Out Of

Football" or "Ban This Man For Life." All those journalists

who hated Leeds United had a wonderful opportunity to bad mouth us. I

got so much press, it was ridiculous. For about two weeks I got pilloried

in every newspaper in the world.

back to top

'None of these journalists had even seen the programme.

They didn't take the trouble to check if I had been quoted correctly.

Acting as judge and jury, they rushed to condemn me. I refused to speak

to any of them. I'd say, "If you see the programme, I'll talk to

you. Ask the questions about the programme, but see the programme first."

None of them could be bothered - or perhaps they didn't want to know the

truth.

'At the time, there were in the Football League a lot of

players whom the critics liked to call hard men. I suppose I was one of

them. But I was never what you consider a dirty player - in my position

I couldn't afford to be, because you can't afford to give away free kicks

near the box.

'Everybody thinks that defenders are the dirty ones in a

side. That's not true - defenders are committed to getting the ball, that's

what they're there to do. Defenders have to be more careful, because if

a defender commits a silly foul in the box, he can give away a penalty.

In fact, giving away a free kick anywhere around the box is not likely

to please the manager.

'In my experience, it wasn't the big lads who were the culprits.

People like Tommy Smith were as hard as nails - but they were never nasty.

They usually tackled hard, but providing the ball was there to be won

and their timing was right, that was OK. The ones you had to watch out

for were the little fellows, the ones who normally played on the wings

or in midfield. They were invariably late in the tackle, always leaving

something there for you to hit. A guy has left his foot there, and when

you follow through, you hit six studs with your shin. Let me tell you

something, it doesn't half hurt.

'Referees and linesmen follow the play, and very often miss

the incident which happens a split second after the ball has been struck.

'There was a spell in the Football League when full-backs

were getting sent off regularly for attacking wingers. And nobody in authority

ever questioned the reason. But those of us playing the game knew what

was happening. And it had to do with incidents like the one I've just

mentioned.

'And there were other nasty ploys in the game. As a centre-back,

my job was to pick up a position for a cross, challenge for the ball and

win it. But the opposing centre-forward didn't necessarily have to win

the ball, and the number of times people have clattered into me late with

their heads or their elbows doesn't bear recounting. You finish up with

your face slashed, elbows in your eye, fingers stuck up your nose, and

so on. I tell you, you get a few headaches. In a lot of cases, the guy

hitting you knows exactly what he's doing. It isn't accidental.

'When I first went to Leeds, I played with a lad called

Albert Nightingale. He was an inside-forward who used to play alongside

John Charles. Albert was notorious in the six yard area. As the ball was

being played into the box, he would tap his opponent on the ankle, the

fellow would howl and grab his foot - and our Albert would be free to

knock the ball into the net. Nine times out of ten, the referee didn't

spot it because he was following the ball, but the other players knew

exactly what had happened, and I saw them chasing him around the pitch

or complaining to the ref.

'Clarkey was a bit like that. Off field he was a great lad

- but he could be a little bit sneaky, with a bit of a mean streak in

him. He would leave the boot in just a bit longer than he should have

done. It caused us loads of aggravation - suddenly all the other side's

defenders would come running after him and we'd have to go and bail him

out. Tommy Smith used to say to Clarkey, "I'll break your back."

'John Giles used to do some awful things to players, too.

We would have rows about it in the dressing-room. I once said to him,

"What do you do it for, John?" And he said, "Well, I once

got my leg broken, and I'm gonna make sure nobody ever does it again,"

meaning that he was going to do everybody before they did him. I said,

"Sure, every bugger in the league is going to get punished because you once got

your leg broke." But it wasn't just them, it was us he was putting

at risk. John caused us a lot of hassle at Elland Road over the years.

It was all so unnecessary, because he was such a skillful player.

every bugger in the league is going to get punished because you once got

your leg broke." But it wasn't just them, it was us he was putting

at risk. John caused us a lot of hassle at Elland Road over the years.

It was all so unnecessary, because he was such a skillful player.

'Playing as a kid of seventeen in the Yorkshire League had

taught me that if you didn't learn how to take care of yourself on a football

pitch, you'd soon get run over. The reality of the game at the time was

that you were responsible for looking after yourself, first and foremost,

and then you looked to the referee for protection. And watching referees'

performances these days, I sometimes get the impression that they think

they are officiating at an amateur game. They frequently miss the mean

fouls, the professional fouls. It begs the question of why more professional

players are not encouraged to become involved in refereeing. I'll tell

you why because the powers that be just don't want to know ex-pros. The

way the system is currently structured, a guy with an uncle on the Northumberland

FA or some other FA has more chance of becoming a Football League referee

than a player with a dozen England caps. It's sometimes who you know,

not what you know, that counts.

'Sports like cricket or rugby league use former players

as officials. I think it's high time that young professional players with

no obvious future on that side of the game were encouraged to take up

refereeing. That way, a lot of the unseemly things we see in the game

today would not go unpunished, while at the same time referees would be

more understanding of the realities of the game, having experienced it

themselves as players.

back to top

'These were the sort of points I emphasised in the Tyne

Tees interview. And I confirmed that there were, of course, vendettas.

When a player's gone and nearly broken your leg, you don't forget it.

When somebody does something that is nasty, you don't forget it. And when

the chance of retribution comes, you take it.

'Any one of a hundred players could have told the FA that,

but still I'm summoned to London to explain myself. Don Revie and the

club solicitor accompanied me. We took a tape of the television programme

with us. As a point of principle, we refused to go to Lancaster Gate.

It had to be a neutral venue for the meeting, away from the eyes of the

media.

'And the first thing which struck me when I walked into

the room was the pile of newspaper cuttings in front of the FA Secretary,

Dennis Follows. It must have been six inches high! "I'm not having

that," I said. "I'm not going to be judged by the reports of

newspaper people acting on second hand information." Don and the

solicitor agreed with me. We told the FA officials that if they wished

to adjudicate fairly, they'd have to watch the film. At that time, television

evidence was inadmissible in FA hearings. But in this instance, we weren't

prepared to budge. They sent us out of the room for almost an hour while

they talked the matter over among themselves. Eventually, we were called

back in to be told, yes, they would watch the film.

'That set a precedent which would soon become standard. Of course, having watched it, they could

only come to the conclusion that my remarks had been taken out of context,

that I had been unfairly reported in the press.

which would soon become standard. Of course, having watched it, they could

only come to the conclusion that my remarks had been taken out of context,

that I had been unfairly reported in the press.

'But still they insisted I apologise. "What for?"

I asked. I hadn't done anything wrong. They'd just gone through the television

evidence and exonerated me. And now they wanted an apology! We must've

sat there for another hour discussing whether I should apologise. "The

people who should apologise," I said, "are the guys who wrote

that pile of crap in front of you." Anyway, we had a little meeting

outside, and Don said, "We've got to apologise in some way."

He said it was in my best interests to make some kind of gesture. I'd

have stayed there for ever rather than give in to them, but eventually

I agreed.

'Only Don could have got me to do that. As a manager, he

was never better to me than at that time, when I was under a lot of pressure

and I needed sound advice. He stood with me through the whole episode

- and I shall always remember him for that.

'What I had to do was to find a way of apologising without

admitting that I'd done anything wrong. And I remember to this day the

final statement that was sent to the newspapers, the same newspapers which

had made headlines of the story for weeks: "I apologise for the fact

that through me, the press was given an opportunity to knock football."

That was the apology we sent to the press - and you can imagine where

they printed it.

'The FA tried me, and I was found not guilty. I was never

fined, never suspended - though I'd suffered two weeks of being pilloried

and having my name blackened all over the world. This was virtually the

start of the sort of bloody journalism we have now. If I pick up the phone

and find there's a journalist that I don't know from one of those papers

on the line, I just put the phone down.

'Unfortunately, there was no big news to take the pressure

off me. On a personal level, the black book incident earned me a reputation

as someone who speaks his mind, someone who says things when he feels

it's necessary to say them. Now, whether I've been naive in this over

the years or not, I don't know, but personally I don't think I have. I

think I've come through my career with a reputation as an honest, straightforward

guy who doesn't pussyfoot around. And I think that's the image most people

have of me.

"And the names in the book? I didn't mention any names in

the programme, and I don't really want to start mentioning names now.

As I've said, I didn't really have a black book - but I did have perhaps

five or six players in mind who had committed nasty tackles on me and

whose names I wouldn't forget in a hurry. You always remember the names

of people who have done you wrong, you never forget them. I'd get them

back if I could. But I would do it within the laws of the game.

back to top

'A lot of people thought that Peter Osgood topped the list

in my black book, but that wasn't the case. Ossie and me did have some

good battles - but I don't remember doing anything untoward in my duels

with him and I can't recall him ever doing anything untoward to me. The

same was true of Denis Law, who's always been a good pal of mine. I've

got two or three of Denis' shirts at home that I ripped off his back.

'Still, I couldn't say the same for Peter's Chelsea club

mate, who did me in the sneakiest way possible in the 1970 FA Cup final

replay when I wasn't even watching him. I haven't caught up with him yet,

so I won't give you his name. As I've said, there was no reason for it

except that I was doing my usual thing of standing on their goal line.

He got away with it at the time, and I can assure you, that rankled for

a while.

'George Kirby, a very competitive centre-forward at Southampton,

was another you had to watch out for, frequently a split second late with

the header and always liable to hurt you. I didn't like that kind of player,

and I remember walking off at the end of a game at the Dell with a bad

headache. Looking back, they were still treating him on the pitch.

'It's more than twenty-five years since the black book was

news, and it wouldn't serve any useful purpose now to start trotting out

names. I'll give just one more example, purely because the player involved,

John Morrissey of Everton, knows the score. We were playing at Goodison

Park one day and John, a short, stocky little lad, was on the wing. I

came across to make the tackle, he went through me, and I ended up having

my foot put in plaster after the game. I still wouldn't have given the

tackle much thought had I not encountered him again on the way out of

the ground.

'Picture the scene - my foot is in plaster, and I'm hobbling

towards the coach with the aid of a stick. He's stood at the door asking,

"How's the leg then, big fella?" And I look across at him and

see this cynical smile on his face - and I nearly flipped. I mean, if

I could have done him then, I would have. "I'll tell you something,"

I said, "if it takes me ten f***ing years, I'll get you back for

this." And I did. But then he got me back, and I got him back, and

so it went on till we finished playing.

'I suppose you could say that I was a bit short tempered.

If somebody did something to me which I thought was unnecessary, I would

react very quickly. That Fairs Cup game

against Valencia was a case in point. I was being abused by some of the Spanish players and I wasn't having that.

being abused by some of the Spanish players and I wasn't having that.

'There was another incident, I think it was in Rome or in Naples, when one

of their guys just turned round and gobbed in my face. I couldn't help myself;

I punched him right in the mouth, and he went down. The referee turned and

saw the guy lying on the floor - you know the way they do, rolling and holding

his face - and he ran back and looked at me as if to ask: what happened?

I didn't say anything, I just pointed to my face. He could see the gob still

there, and he said, "OK, free kick," and he just left the guy

lying there.

'You have these moments of madness when you let fly or go

chasing somebody all over the park after they've done something nasty

to you - until somebody grabs you and slaps you on the face and says,

"Hey, settle down." People forget that in football you're 100

per cent concentrated on the game, you're looking at the game, you're

reacting to the game, your position changes as the ball moves around -

and then somebody does something really nasty, and it snaps your concentration.

That's what happened to me in the 1970

Cup final replay.

'It's just hypocrisy to pretend that a professional footballer

can just forget when somebody does something like that to him. In no way,

shape or form can any pro just forget when somebody's nearly broken his

leg, or split his eye, or smashed his forehead. You know in a split second

if it's deliberate. And as I've said, if you have a chance to get even

later on, you take it. Everyone in the game knew that - except, apparently,

the FA.'

Part 1 - Off like a train - Part

3 - Colchester, Tinkler and Fairs success - Results

and table

The

Committee has decided also that the attention of the Football League be

brought to the matter in the light of Football league regulations 39 (3)

and 74. The Emergency Committee has further decided that until the matter

has been resolved the England team manager should be informed that Charlton

won't be eligible for selection for any FA representative teams.'

The

Committee has decided also that the attention of the Football League be

brought to the matter in the light of Football league regulations 39 (3)

and 74. The Emergency Committee has further decided that until the matter

has been resolved the England team manager should be informed that Charlton

won't be eligible for selection for any FA representative teams.' was

the most significant thing.

was

the most significant thing. ridiculous as the British public in one of its periodical fits of morality"

and it was exactly one such fit which now had Jack Charlton at its centre.

"These sickening comments," ran the headline in the Daily

Express, above an opinion piece by sports editor John Morgan which

called for Charlton to be sacked by Leeds: "The damage caused by

the words Charlton used cannot be estimated in the effect it will have

on hundreds of youngsters. The damage abroad will show in the inevitable

repercussions years hence." In the Daily Mirror Peter Wilson

asked: "Have these petulant, primping, over-paid, under-principled

gladiators no responsibility?"

ridiculous as the British public in one of its periodical fits of morality"

and it was exactly one such fit which now had Jack Charlton at its centre.

"These sickening comments," ran the headline in the Daily

Express, above an opinion piece by sports editor John Morgan which

called for Charlton to be sacked by Leeds: "The damage caused by

the words Charlton used cannot be estimated in the effect it will have

on hundreds of youngsters. The damage abroad will show in the inevitable

repercussions years hence." In the Daily Mirror Peter Wilson

asked: "Have these petulant, primping, over-paid, under-principled

gladiators no responsibility?" Norman

Harris was in Jack's house at the time of the crisis and, in a diary piece,

described the reaction to Bobby's article: 'There is now some dissension

in the family, and unpleasantness in a phone conversation between the

two brothers." Then Cissie took up the cudgels against Bobby, no

longer the favourite son since his marriage to Norma: "I am amazed

at our Bobby," she told the Daily Mail, "he's in the

same position as all of Jack's other critics. He hasn't seen the television

programme." And she added, in defence of Jack, "Everyone knows

Jack is not a dirty player. Where has everyone's sense of humour gone?"

Norman

Harris was in Jack's house at the time of the crisis and, in a diary piece,

described the reaction to Bobby's article: 'There is now some dissension

in the family, and unpleasantness in a phone conversation between the

two brothers." Then Cissie took up the cudgels against Bobby, no

longer the favourite son since his marriage to Norma: "I am amazed

at our Bobby," she told the Daily Mail, "he's in the

same position as all of Jack's other critics. He hasn't seen the television

programme." And she added, in defence of Jack, "Everyone knows

Jack is not a dirty player. Where has everyone's sense of humour gone?" there

is a violence within him." Again, Storey-Moore argues that, though

"Jack was not the worst of the Leeds, team, he did have a violent

temper. If someone upset him in a game, I think he would certainly make

sure he left his mark on that player."

there

is a violence within him." Again, Storey-Moore argues that, though

"Jack was not the worst of the Leeds, team, he did have a violent

temper. If someone upset him in a game, I think he would certainly make

sure he left his mark on that player." every bugger in the league is going to get punished because you once got

your leg broke." But it wasn't just them, it was us he was putting

at risk. John caused us a lot of hassle at Elland Road over the years.

It was all so unnecessary, because he was such a skillful player.

every bugger in the league is going to get punished because you once got

your leg broke." But it wasn't just them, it was us he was putting

at risk. John caused us a lot of hassle at Elland Road over the years.

It was all so unnecessary, because he was such a skillful player. which would soon become standard. Of course, having watched it, they could

only come to the conclusion that my remarks had been taken out of context,

that I had been unfairly reported in the press.

which would soon become standard. Of course, having watched it, they could

only come to the conclusion that my remarks had been taken out of context,

that I had been unfairly reported in the press. being abused by some of the Spanish players and I wasn't having that.

being abused by some of the Spanish players and I wasn't having that.