|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

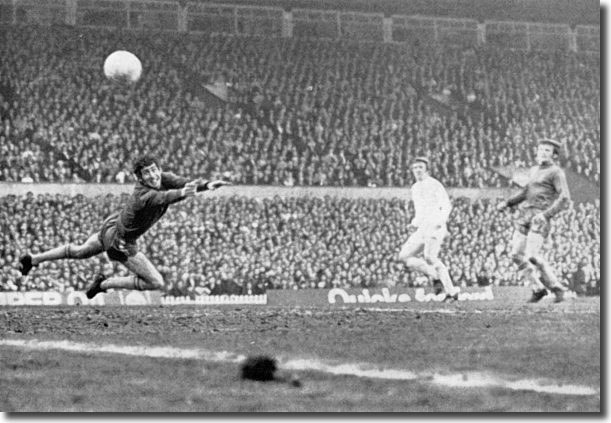

FA Cup final replay - Old Trafford - 62,078

Scorers: Jones

Leeds United: Harvey, Madeley, Cooper, Bremner, Charlton, Hunter, Lorimer, Clarke, Jones, Giles, Gray

Chelsea: Bonetti, Harris, McCreadie, Hollins, Dempsey, Webb, Baldwin, Cooke, Osgood (Hinton), Hutchinson, Houseman

They had given a wonderful exhibition, all the more remarkable taking

into account the appalling state of the pitch. Geoffrey Green of The

Times reported, perhaps overstating the case a little, 'What must

be beyond dispute is that here, technically - remembering the killing

conditions - was the finest Cup final seen at Wembley since the war, better

even than Manchester United and Blackpool of 1948 and lacking only the

emotional impact of the last 20 minutes of the Stanley Matthews fiesta

of 1953.' But, if the game demonstrated a lot that was great about English club

football, the replay that followed two and a half weeks later at Old Trafford

won a reputation for being the dirtiest final ever. Three decades later former referee David Elleray reviewed a DVD of the

match against the standards set by modern day refereeing. He came to the

conclusion that Leeds should have had seven bookings and three dismissals

(Giles, Bremner and Charlton), while Chelsea deserved 13 bookings, including

three each for Webb, Harris and Cooke. The referee in charge of the actual game, Stourbridge's Eric Jennings,

took a laissez faire approach to the contest, offering plenty of leeway

and booking just one player, Ian Hutchinson of Chelsea. Blues midfielder

John Hollins would later say, 'People were standing up to each other,

head-to-head, as they do nowadays except they were hitting each other.

The ref would say, 'Play on, keep going'. He played great advantage. If

he had stopped it, there would have been an incident. The incident didn't

happen because he simply played on.' 47-year-old Jennings was in his last season as a Football League referee

having reached the maximum age in January and had enjoyed sixteen years

as a first class official, running the line in the 1958 Cup final and

officiating in the 1967 Amateur Cup final. He had some history with Leeds:

in November 1963 he had been forced to stop play and call together both

sets of players to appeal for calm when United were involved in something

of a bloodbath against Preston; in May 1966 he had to do the same during

an ill-tempered clash against Burnley at Turf Moor. Johnny Giles: 'There was so much stick flying around, I have to admit

it was pretty horrendous, and I make no excuse for it. But we did have

some strange code of honesty ... I'm sure of two things. One is it that

it was inevitable the game would come to its senses, and that no one who

played or managed the game back then would have had any part of today's

culture of diving. Then you took stick and you handed it out, but you

couldn't imagine faking injury or trying to get a player sent off. Maybe

he would be carried Chelsea's Alan Hudson, who missed both the final and the replay through

injury: 'Tommy Baldwin and Terry Cooper, two of the quietest men in football,

kicking lumps out of one another as the battle began. Tommy, a prolific

goalscorer when given the opportunity, was handed strict orders not to

allow the weaving Leeds full-back to get too far over the halfway line,

if over at all. Ron 'Chopper' Harris did not need any telling. His scything

tackle on the wing wizard Eddie Gray in the opening minutes was chilling.

That set the pattern of the match. It was the only way we could have won

it, by fighting white fire with blue fire, and the outcome was for all

to see. Someone joked that Gray was picking Chopper's studs out of his

shins well after that final whistle. He collected more shrapnel in that

game than a veteran of the Somme in World War One!' The Independent: 'The match provided a lengthy sheet of misdemeanours.

Chelsea's hard men systematically targeted Gray, and Harris finally nailed

him late in the first half with a malicious kick on the back of the left

knee. Moments later, Charlton headbutted

and kneed Osgood after the Chelsea striker had tackled him from behind.

Wherever you looked on the field there was mayhem, as players kicked,

gouged and butted each other with impunity. The next morning, one paper

summed up with the banner headline "Robbery With Violence"'. The game was awaited with great anticipation following the excitement

of the first contest, but Chelsea set their stall out to prevent Leeds

from enjoying the dominance they had at Wembley. Eddie Gray had given

David Webb a roasting and now manager Dave Sexton switched Webb and Harris,

lining the famous Chelsea hard man up against Gray with the intention

of kicking him out of the game. Webb's reckless challenges were more easily

compensated for in the centre of defence, where his colleagues could offer

him greater protection. It was clear from the first seconds that Harris would be closely shadowing

Gray, denying him the time and space that he enjoyed at Wembley. Conversely,

Lorimer and Jones were far more dangerous than in the first game, pulling

defenders all over the place and constantly threatening. Sexton also switched the roles of Peter Houseman and Charlie Cooke. As

Geoffrey Green wrote, 'It will be Cooke's job now to ferret and supply

his forwards from the rear, joining into attack himself, of course, as

the situation warrants, and leaving Houseman to float down the left flank

in his accustomed fashion. It was Cooke's astute reading of the situation

last time, when he sustained Chelsea's flagging spirits by doubling back,

supplementing midfield and dribbling cleverly to win time and space that

helped to save the day for the south. It was this, no doubt, that influenced

Dave Sexton, the Chelsea manager, to rethink his line-up.' For Leeds the only change was reserve goalkeeper David Harvey coming

in for Gary Sprake, who had been injured in the European

Cup semi-final against Celtic. Harvey commented, 'I'm very sorry for

Gary, and I hope I don't let him or the side down.' Heavy rain fell for hours on the Old Trafford pitch on the day of the

game, and Don Revie smiled, 'I am

happy to see the rain. The ground will suit us much better if it is soft.'

He went on, 'Naturally we are very confident but we must put the Wembley

match right out of our minds. We cannot use that as a yardstick for what

will happen at Old Trafford. We must treat both matches as entirely separate

events.' With a television audience estimated at 32m watching the game live, Leeds

kicked off and were instantly onto the attack - within the first minute

Lorimer's cross hit Dempsey and the deflection almost took it into the

Chelsea net. Then Gray had a sprint down the left touchline and used his

pace to go round Harris; he managed to get in a smart low cross before

the tackle came in. Mick Jones flicked the ball on with Webb unable to

get to him and Bonetti got down well to touch the effort wide. After 12 minutes Chelsea had another escape. Cooper's long centre swung

away from Bonetti and Lorimer turned it back across goal. Gray could have

shot but returned it to Lorimer. He went for the spectacular and only

succeeded in sending the ball miles wide of goal. United continued to press and for the ten minutes up to the half hour

they ratcheted up the pace, forcing Chelsea back onto desperate defence.

There was an exchange of punches between Hunter and McCreadie as tempers

frayed and with the crowd's attention diverted, Gray took the opportunity

to run into space, his shot running narrowly wide. In the 25th minute, Dempsey attempted a back pass to Bonetti with the

keeper miles away from his station. Lorimer beat him to the ball, only

to see his shot from an acute angle saved on the line by McCreadie. It required a tremendous Dempsey tackle to prevent Clarke capitalising

on a long ball from Lorimer. In turn the Scot hammered a right-footed

drive narrowly wide. Jones got into the action by putting an effort into

the side net from close range after Giles had combined with Gray down

the left to create the opportunity. On the half hour Bonetti was injured in an aerial clash with Jones as

the two went for a steepling Madeley centre from the right. There was

a mass protest from Chelsea at what they saw as flagrant foul play. Action

was held up for three minutes for the keeper to get treatment and he was

badly limping when he restarted. The handicap didn't stop him from continuing

to substantiate his long-held status as arch nemesis of Leeds United forwards. Chelsea responded furiously to what they saw as intimidation by launching

an all out assault on the United goal. It cost them heavily, for in the

36th minute Leeds took a deserved lead after coolly playing themselves

out of trouble. Harvey's throw out of his goal area was picked up by a Chelsea man who

tried to He slipped the ball short to Jones 40 yards out and let his partner carry

the move on. The centre-forward set off on a storming run, coming away

from Hollins and Harris and resisting intense pressure from McCreadie

to make his way into the right hand side of Chelsea's area. From there

he hammered a thunderous right-footed shot across Bonetti and into the

net. Geoffrey Green in The Times: 'It was a goal from the past, as

old-fashioned as the horse and carriage. It revived memories of Ted Drake

in his heyday.' Leeds took that well-deserved lead into the break. Almost immediately after the resumption Cooke and Clarke started kicking

seven bells out of each other. Referee Jennings turned a blind eye, as

he had throughout the first half, but finally, there came an incident

which even he could not ignore. Charlton and Osgood were involved in a

scramble near the touchline and the striker took Charlton out. The big

man completely lost it, got to his feet, stormed after Osgood and scythed

him mercilessly to the ground. Even then Jennings merely gave them a severe

talking to and no names were taken. It was the 65th minute before the

referee's tolerance was finally tested too far. Osgood and Bremner tangled

and when the Scot appeared to be hacking at the fallen Chelsea man, the

referee thought it worth only another cool glance. So Hutchinson rushed

up impetuously to push Bremner to the ground and was cautioned. It was

the only booking of the night. Around the same time Harvey confirmed his worth as Sprake's deputy. He

had given a brave and effective performance whenever called upon and his

save from a close range Baldwin header after Madeley had failed to prevent

the opportunity was outstanding. But Leeds still drove forward, pressing to increase their lead. Hunter

won a ball from a Chelsea defender 25 yards from the Blues' goal line

and slipped it to Gray out wide on the left. He flicked it back to Cooper

who played the ball forward and twisted and turned round two defenders

to catch it and loft over a cross from the byline. Jones challenged a

defender in the air and the ball ran out to the edge of the area for the

onrushing Giles to strike low for the bottom corner. It was deflected

by a Chelsea man and scraped the post and the side netting with Bonetti

stranded. Cooper, as if intent on exorcising the ghost of Celtic's Jimmy Johnstone

and the personal nightmare that was the European Cup semi-final, was in

superb attacking form throughout the game. Moments later, he set off on

another storming run through the heart of the Chelsea defence to hammer

a shot right-footed from the edge of the area which Bonetti could only

push away. Geoffrey Green: 'By now Osgood, Cooke and Hollins had begun to play beautifully,

moving the ball smoothly in flowing moves of unexpected angle. Suddenly,

they began to burn some magic fuels. Here was the echo of Wembley again.

Having been largely overplayed there for a long period, as now, they began

to come at the right moment. The change in the tide, and the feeling it

communicated to the packed company, gave 'Where once the great steam roller of Leeds had driven forward, with

Giles and Bremner putting Jones, Gray and Lorimer into full stride, and

with Clarke adding some highly cultured and sensitive touches, it had

all been one way. Now it was the elegant Osgood, the elusive Cooke and

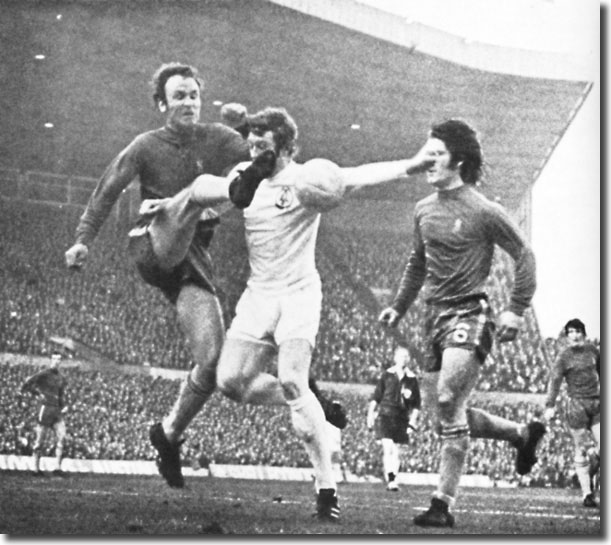

the non-stop Hollins who oiled Chelsea's wheels at last. 'With 10 minutes left they suddenly were level. Theirs, too, was a beautiful

goal: more complicated, more finely ingrained, more liquid and created

virtually out of nothing. Here was the poetry of football and it came

with a magical exchange of passes between Hollins, Hutchinson, Osgood

and then the hard-running Cooke. Over came Cooke's perfect chip and there

was Osgood infiltrating from the left to the blind side to head a magnificent

goal.' There was a clear lack of concentration in United's defence; Osgood found

a huge gap with five United defenders stood round him looking on and querying

pathetically who was picking the striker up. For a team with the mean

defensive reputation of United, it was an astonishing lapse. Jack Charlton: 'I blame myself for that goal. I'd been waiting on their

goal line for a corner kick when one of the Chelsea players - someone

who'd better remain nameless - whacked me in the thigh with his knee.

After the corner was cleared I started to chase him, way over to the right.

Then the ball was knocked in long to our box and I started to run back,

but I was still hobbling after the whack in the thigh and I couldn't get

there in time to stop Peter Osgood heading his goal.' Charlton's defensive partner, Norman Hunter, writing in his autobiography,

also accepted the blame for allowing Osgood a free run, despite a shouted

warning from Paul Reaney from the sidelines. In the normal time that remained there was some fierce and frenetic action.

Bremner was heavily involved: United had justifiable claims for a penalty

ignored when McCreadie appeared to be intent on decapitating his Scottish

international colleague. For the umpteenth time Cooper went racing down the left wing and lofted

in a high centre. It bounced out from an aerial challenge and McCreadie

leapt up feet first into a wild and dangerous high kick that took Bremner

in the forehead. The Scot was left writhing on the ground holding his

head for what Referee Jennings saw Cooper pick up the ball and shape for a shot. He

played advantage but none was taken as Chelsea blocked the chance. Osgood

and Hutchinson went away to fashion an opportunity which ran narrowly

wide of Harvey's post. Bremner required lengthy treatment from trainer

Les Cocker before he was anywhere near fit to carry on. Following that he tangled heavily with Hutchinson and received a rebuke

from Jennings; and finally he was sent crashing to the ground as he raced

in on goal, reacting angrily when more penalty claims were refused. Jones nearly snatched an injury time winner with a flying header at a

Lorimer cross but the ball went narrowly wide. 210 minutes of football had failed to produce a decision and the two

teams thus had to line up for another 30 minutes of hard labour. Don Revie sought valiantly to rally his men to one last effort in an

extraordinary season, imploring them for one final push. He got a response,

despite the tired limbs and minds, but it was the Londoners who rose to

the occasion at the last to get their noses in front. One minute before the end of the first period of extra time, Chelsea

broke the deadlock, taking the lead for the first time in this marathon

contest. The goal was created by one of Hutchinson's trademark whirlwind long

throws from Chelsea's left touchline 30 yards out. Charlton met the ball

at the front post but could only succeed in allowing the ball to flick

off his head in a lofty and inviting arc across the face of his own goal.

Harvey had tried to come through and punch clear but couldn't find an

avenue past Charlton. In the melee that followed Webb rose above Gray

and Cooper at the back post to bundle the ball home with his head. That reverse should have been enough to kill off any fight that remained

in the exhausted Leeds men, but they forced themselves into a final throw

of the dice, throwing everything into desperate,

headlong attack. It was a wild eyed attempt to claw something from an

amazing season that, when once so much glory had beckoned, now

promised to leave them empty handed. Osgood was replaced with That was a rare excursion upfield for Chelsea as virtually the entire

fifteen minutes were played out in and around the Londoners' area. Leeds could not turn their late domination into a goal and were left

distraught at the end of four hours of combat. Charlton stormed off the

field ahead of anybody else - not bothering to collect his runners up

medal - furious that Leeds had lost. He said later, 'The disappointment

was incredible. I went straight to the dressing room and kicked open the

door. I've never been more upset over losing a game, maybe because it

was partly my fault. Nobody else came into the dressing room, and I just

sat there and sat there for ages, before all of a sudden the lads started

to drift in with their losers' medals. It was only then I realised I hadn't

collected my own medal. To this day I'm not sure if I ever got it - though

I suppose I must have done.' It was the most galling and inequitable of setbacks for a club that had

become hardened by a succession of near misses over the previous six years. The Yorkshire Post: 'Victors take the plaudits, losers only consolation

in Cup football, but Leeds can draw justified solace from an unqualified

success last night - in their ability to entertain. Leeds' manager, Don

Revie, promised a more adventurous, more attractive Leeds United at the

start of the season and their last match bore indelible testament to the

fruition of his aim. Leeds went forward as though they had never learned

how to defend - by necessity in the final analysis but from choice for

most of the match - and wove into their determination strains of admirable

skill and invention from Gray, Clarke, Bremner and Cooper. 'They had entertained magnificently; they had achieved more in failure

than most clubs in success, but the league championship had eluded them,

the European Cup had eluded them, and now the FA Cup had slipped away.

There is nothing so cruel as melted visions of what might have been ...' Don Revie, clearly dejected after the game, admitted, 'This is the biggest

disappointment of all. Coming after two defeats and after we had put the

pieces together it is bitterly disappointing - more so for the players

than for myself. I thought we played as well in the first half as we did

at Wembley, despite Chelsea's tactical moves, and they didn't score until

their first real attack. 'We were pushing the ball around well and might 'David Harvey did an excellent job for us. We have the type of players

with the character to come back next season, and if anyone says to me

at the start of next season that we can finish second in the League and

runners up in the Cup final I will be well satisfied. 'I am sick and disappointed more for the players than for myself. Now

we'll have to start all over again. I think it was bound to catch up on

us. There have been no easy matches.' Geoffrey Green in The Times: 'Leeds, like Sisyphus, have pushed

three boulders almost to the top of three mountains and are now left to

see them all back in the dark of the valley. 'Should it be any consolation to them, Leeds have now probably won something

more in defeat as good losers than they would have done in many hours

of victorious celebrating - universal public sympathy. They have done

their image good.' Leeds

United failed to defeat Chelsea in the 1970 FA

Cup final at Wembley on 11 April, but in every respect other than

the scoreline, they were streets ahead of their fierce London rivals,

striking the woodwork on three occasions and dominating the game. They

also had the consolation of finally doing themselves justice in a Wembley

final, expunging the dire memories of 1965

and 1968, when they had played in two of the

worst games in the stadium's history.

Leeds

United failed to defeat Chelsea in the 1970 FA

Cup final at Wembley on 11 April, but in every respect other than

the scoreline, they were streets ahead of their fierce London rivals,

striking the woodwork on three occasions and dominating the game. They

also had the consolation of finally doing themselves justice in a Wembley

final, expunging the dire memories of 1965

and 1968, when they had played in two of the

worst games in the stadium's history. off,

but that would be another matter.'

off,

but that would be another matter.' set up a chance. A United defender nicked the ball and Gray brought

play away via a cool one-two with Giles before feeding on to Clarke, ten

yards inside his own half on the left touchline. He set off on a wonderful

diagonal run, escaping three heavy challenges from different Blues men.

Each time it looked like he would be clattered but a combination of pace

and deft feints and swerves took Clarke through the eye of a needle and

left the defenders sprawling in his wake.

set up a chance. A United defender nicked the ball and Gray brought

play away via a cool one-two with Giles before feeding on to Clarke, ten

yards inside his own half on the left touchline. He set off on a wonderful

diagonal run, escaping three heavy challenges from different Blues men.

Each time it looked like he would be clattered but a combination of pace

and deft feints and swerves took Clarke through the eye of a needle and

left the defenders sprawling in his wake. out an intense radiation. It

almost dislocated the senses.

out an intense radiation. It

almost dislocated the senses. seemed an age.

seemed an age. eight minutes to go by Hinton as the Londoners

manned the defensive barricades, but he set up an opportunity for Hutchinson

before he departed, with Harvey left unprotected as his team chased a

late equaliser. Hutchinson put the chance away but the goal was disallowed

for offside.

eight minutes to go by Hinton as the Londoners

manned the defensive barricades, but he set up an opportunity for Hutchinson

before he departed, with Harvey left unprotected as his team chased a

late equaliser. Hutchinson put the chance away but the goal was disallowed

for offside. have had more goals.

Chelsea marked Eddie Gray much tighter this time but we moved him inside

and he got into the game. I have nothing but admiration for the lads because

this was their 64th game of the season and everyone has been full of tension.

They have worked hard, trained hard and played well yet at the end of

the road there has been nothing for them.

have had more goals.

Chelsea marked Eddie Gray much tighter this time but we moved him inside

and he got into the game. I have nothing but admiration for the lads because

this was their 64th game of the season and everyone has been full of tension.

They have worked hard, trained hard and played well yet at the end of

the road there has been nothing for them.