|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

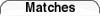

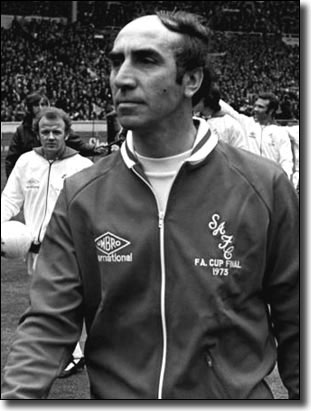

FA Cup final - Wembley - 100,000

Scorers: None

Leeds United: Harvey, Reaney, Cherry, Bremner, Madeley, Hunter, Lorimer, Clarke, Jones, Giles, E Gray (Yorath 77)

Sunderland: Montgomery, Malone, Guthrie, Horswill, Watson, Pitt, Kerr, Porterfield, Halom, Hughes, Tueart

'Everything points to a United victory' read the unusually

confident headline of Don Revie's

column for the Yorkshire Evening Post the Saturday before the final.

The Leeds manager was in buoyant mood, writing: 'Leeds United's experience

of playing at Wembley is likely to prove the decisive factor in next Saturday's

FA Cup final against Sunderland … As far as the FA Cup final is concerned,

I consider the Sunderland players will suffer to a certain extent as none

of them has played at Wembley previously. 'This will be Leeds' fifth Wembley Cup final in eight years

(including the 1968 League Cup final against Arsenal).

Apart from this, most of the players have also appeared on this ground

in international matches. With such a background, they are less likely

to be affected by the tension of the occasion. Playing on the Wembley

turf for the first time can prove a tremendous ordeal … as, indeed, I

discovered when making my FA Cup final debut for Manchester City against

Newcastle United in 1955. 'I found it almost impossible to relax in the weeks leading

up to the final, when City were caught up in the traditional Wembley ballyhoo.

During this period, all the players are inundated with requests to attend

special functions, endorse various products and do newspaper, radio and

TV interviews and it is always difficult to know where to draw the line

if you haven't encountered this type of problem before. 'Any player who has appeared in the Cup final will no doubt

confirm that the most nerve wracking moment comes about 20 minutes before

the kick off. You feel the sweat waiting in the tunnel for the signal

to take the field. Believe me, those 'I was very tense during the early part of the game, when

my legs felt as heavy as lead and I just couldn't get going. This was

true of all the City players and Newcastle, slightly the more experienced

of the two teams, took advantage by going ahead in the first minute. They

eventually won 3-1. 'No doubt, Sunderland's manager Bob Stokoe, ironically Newcastle's

centre-half against City in 1955, will spend a lot of time next week telling

his players what to expect … but I doubt whether his advice will fully

compensate for their lack of experience. 'This final will present a tremendous challenge to the Leeds

players as, since the war, only two clubs have won the FA Cup for two

years in succession, Newcastle (1951-52) and Tottenham (1961-62). If only

because of our big match know how I must rate our chances of becoming

the third.' The experience upon which Revie laid such heavy emphasis

was epitomised by his Irish schemer, Johnny Giles, making a fifth appearance

in the Wembley showpiece. He was only the second player in 60 years to

do so, repeating the feat of Joe Hulme, who did the same for Huddersfield

and Arsenal. Giles commented, There is nothing quite like reaching the

FA Cup final. Playing in such a game at Wembley is fantastic. There is

nothing really to rival the feeling of Cup final day when you are taking

part. I am looking forward to this game against Sunderland just as much

as I did my first final when I was at Manchester United. I am as excited

now as I was then.' Away from the frothy veneer of the media's Cup final previews,

there was a darker story of revenge and mind games unfolding. Bob Stokoe,

appointed as Sunderland manager in November when they were fourth from

bottom of Division Two, had inspired an astonishing upturn in the Wearsiders'

fortunes. The North Easterner held a bitter grudge against Don Revie,

dating back to 1962 when, Stokoe

maintained, Revie had attempted to bribe him to throw a match against

United when he was player-manager of Bury. Playing up his avuncular image, Stokoe launched a master

class in public relations in Cup final week to undermine Revie and United,

as outlined by Rob Bagchi and Paul Rogerson in The Unforgiven. 'Bob Stokoe was an even more virulent critic of Revie than

Clough. It was the definitive David versus Goliath encounter. A team from

the Second had not won the FA Cup since 1931 and, under-standably, the

media consensus was that Sunderland did not have a prayer against probably

the finest club side in Europe. "No way Leeds can lose it,"

asserted the Daily Mail on the morning of the match. While Revie

made his routine noises about respecting his opponents, in private he

was less equivocal. "Before the game I could not see any way we could

lose," he later admitted. "We had the players, the experience,

the firepower and the team spirit." Ever-cautious, however, he would

not countenance any public display of confidence, and once again this

would contribute to his team's undoing. As his squad set off for London,

he explained how the "quiet route to success" meant treating

this game ''as just another match". 'It was a catastrophic misjudgement. A carefree Sunderland

had been grandstanding in London for days, 'Rather than dismissing or simply ignoring Stokoe's absurd

gripe, Revie unwittingly revealed that it had fed his neurosis, commenting

wearily that, "We get blamed for practically all it is possible to

get blamed for these days." Wolves manager Bill McGarry's attack

of sour grapes gave Stokoe more ammunition, as he declared himself "staggered",

in the aftermath of his side's semi-final defeat,

"at the way Bremner went the whole 90 minutes disputing every decision

that went against his team". "I am not trying to knock Leeds

in any way," agreed a disingenuous Stokoe, "but we are playing

a real professional side and, let's face it, the word professionalism

can embrace a multitude of sins as well as virtues. The case about Bremner

is the only comment I want to make about Leeds. My message is simple.

I want Mr [Ken] Burns, the Cup Final referee, to make the decisions and

not Mr Bremner." Holed up in the team's hotel, Bremner declined to

get drawn into a slanging match. "It's like Wilfred Pickles' 'Have

a go' week" was the Leeds captain's gnomic response. 'It is impossible to prove that Stokoe's bid to prejudice

Burns had an effect on the outcome of the match, but when the game came

around, the Leeds captain would be uncharacteristically out of sorts.

We also know that Burns' relations with Leeds had been strained since

the 1967 semi-final. Certainly the Sunderland boss had no doubts: "[The

media] did a marvellous job for me," confirmed Stokoe, proving himself

a master of the gamesmanship he had so hypocritically con-demned to some

credulous journalists. "I'm not saying the referee was influenced,

but he didn't allow Bremner to get at him." 'By the morning of the match the Leeds players were unsettled,

their manager's innate anxieties heightening their own. A team used to

snapping and scrapping and battling against the odds was acutely uncomfortable

in the role of overwhelming favourites. One photographer in the team hotel

who was rash enough to take a picture of the team had his camera torn

from his hands. Revie did not like the team being photographed before

games - another daft superstition. 'Dave Watson, the craggy Sunderland centre-half who would

later play under Revie for England, recalled watching the Leeds players

being interviewed at their hotel. "They were very subdued,"

he observed. "No one was cracking any jokes. The answers were very

clipped, as if they were afraid to give something away. We thought: What's

wrong with them?" Sunderland's mood could not have been more different.

"Our lot were the complete opposite, clowning around," said

Watson. "We all fell about. Bob Stokoe was there, with one of the

directors, and everyone was splitting their sides ... everyone except

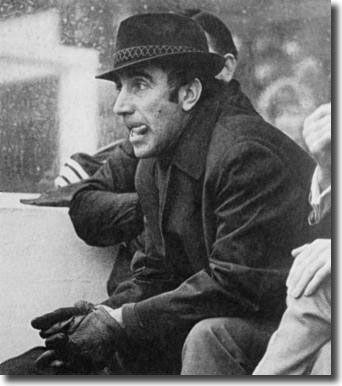

[ITV's match commentator] Brian Moore." Stokoe The day was a wet one in London, and as Clarke and Jones

kicked off for Leeds, light rain continued to fall incessantly. The pitch

was in decent condition and seemed perfect for football, though it would

later start to cut up a little under the prolonged showers with several

players losing their footing on the greasy surface. Stokoe had obviously done his job well: Sunderland were

supremely motivated for the game, brashly enthusiastic and full of running,

determined not to let their illustrious opponents settle into the game.

They were up and at United from the very start, hassling and harrying

and denying them space and time. Hunter had to block a long range shot

from Dennis Tueart as Sunderland swept straight onto the offensive. The Observer: 'The first three minutes were ominous:

a violent foul by Richie Pitt on Allan Clarke, then a repetition of the

same offence, and there were three successive passes, by Norman Hunter,

Bremner and Johnny Giles, which were remarkable for their massive misdirection.

The inevitable, taut nerviness and enough rain on the pitch to produce

miniature fountains whenever the players struck the ball hard combined

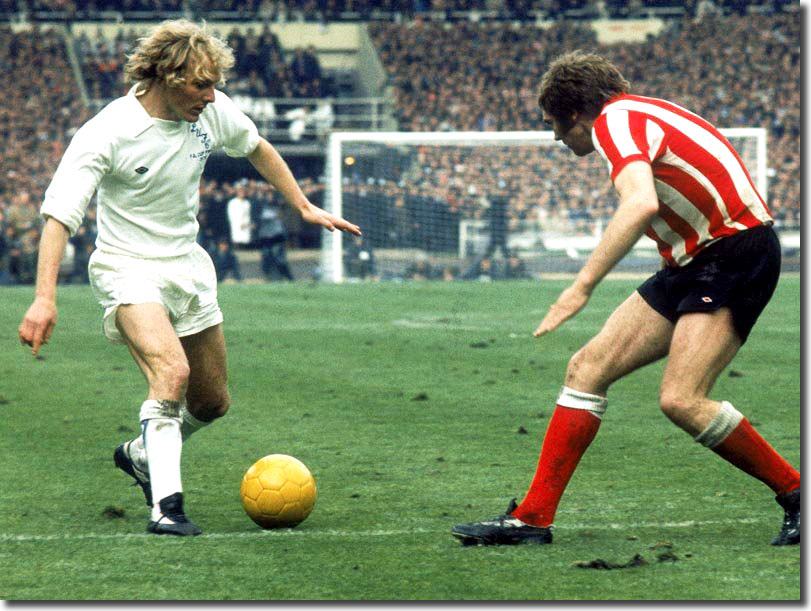

to produce a great deal of error.' From an early free kick, Peter Lorimer struck a low, hard

drive into the area and Mick Jones was fractionally short of getting a

vital touch on it as it sped across the face of goal. But Sunderland refused

to be overawed and it was they who had the first shot in anger after twelve

minutes. Billy Hughes sought to round off a fluent passing movement with

a strike from 20 yards but his effort flew high and wide of Harvey's goal. Hunter brought Leeds back onto the attack with an incisive

run which took him to the Sunderland area. He took on Black Cats skipper

Bobby Kerr at the byline and managed to get a cross round him and towards

the front post. Lorimer attempted a flicked volley from an acute angle,

but the ball flew wide. Sunderland snapped back and came close to a goal on the

quarter hour. From a throw on the left Porterfield found full-back Guthrie

coming forward. His curving cross was headed out by a diving Reaney from

the edge of the area, but only to the unmarked Horswill. The midfielder

sized up his shot from 22 yards as Madeley came at him and saw it fly

inches wide of Harvey's right hand post with the keeper struggling to

reach it. Back towards Montgomery's goal poured Leeds, Giles coming

inside off the right wing to float a high ball to the heart of the Wearsiders'

area. From the aerial challenge, the ball came back to Bremner, who fed

Lorimer to the right. He worked his way into space and looped over a cross.

Jones and Clarke both went for it, but full-back Malone got the vital

header to deny them Leeds pressed again, with Madeley spearing a beautiful through

ball towards Clarke near the penalty spot. As the striker was turning

to get in his shot, Watson came flying in to deflect the ball away. Minutes later Clarke's name was the first to go into the

referee's book as he helped out in defence, bringing down Hughes from

behind. After 24 minutes, it seemed Hunter might follow suit when he kicked

out wildly at Tueart. The Sunderland wide man needed treatment to his

injured shins but Hunter escaped without a caution. If those unsavoury moments hinted that the game might descend

into outright violence, there was little else to concern referee Ken Burns,

though play in the first half brought huff and puff rather than any meaningful

football. Sunderland hinted at a threat when Hughes rounded Reaney

on the left but Hunter managed to clear up the danger and bring the ball

out of his defence. The game's first corner went to United in the 26th

minute after Malone headed behind under pressure from Clarke. Cherry got

to the corner to try his luck with a shot, but saw it deflected over the

bar. United were rocked to their foundations five minutes later

when the Second Division side took a shock lead from their first corner

of the game. A smooth Sunderland passing movement brought them into the

United half and gave Kerr the space for an impudent chip from range which

came plopping down under David Harvey's bar. With Hughes racing in, the

keeper opted for safety first and tipped the centre-cum-shot over his

crossbar. United's preoccupation with Dave Watson's aerial threat

at corners was their undoing. Hughes sailed the flag kick out to the far

post where Watson was waiting, with Madeley and Jones ready to compete

with him. In the eventuality, the ball beat all three of them as they

tussled, and sailed on to bounce off the chest of the incoming Vic Halom. It fell nicely for Porterfield Sunderland were ahead! The stadium erupted in celebration as the excited Sunderland

lads mobbed the scorer. It was exactly the inspiration the outsiders needed,

and, urged on by what seemed the entire stadium, they pushed for a second. Hughes was proving an enthusiastic and mobile force in the

Wearsiders' front line. He made ground on the right and Harvey could not

reach his centre. There were no takers, however, until Horswill got to

the ball but he was stopped in his tracks by Giles' challenge. United, deafened by Sunderland chants, were forced to soak

up more pressure as the interval dawned, though they fashioned a little

pressure of their own. Lorimer had two shots blocked, one by a defender

and the second by Montgomery, who was thankful to see the ball rebound

clear, for he had no control as the shot rocked him on his heels. It was all hands to the pump for a period as United stoked

up the pressure in the Sunderland area, but always there was a man in

red and white stripes throwing himself into challenges and blocks to parry

some hurried shooting from Leeds. Half-time came with Sunderland still ahead and they had

every reason to be proud of their first half performance. They had been

the more forceful side. United had been unable to get a grip in midfield during

the first half but they restarted with a renewed sense of purpose. Clarke,

Lorimer and Madeley all had a go at prising open a solid defence at the

heart of which Watson was a resolute rallying point. Bremner made space for himself on the edge of the Sunderland

box after 49 minutes, wrongfooting Pitt with a lovely drag back. He flashed

in a left footed shot which came back off the goalkeeper but there was

no Leeds player close enough to capitalise and Malone was happy to put

it behind for a corner. United continued to exert pressure and Cherry had the ball

in the net a minute later. Bremner lofted a free kick from the right touchline

deep into the Sunderland six-yard box and when Montgomery rose to claim

the centre, Clarke barged into the keeper, causing him to drop the ball

as he fell. Cherry was on hand to poke home the loose ball, but Leeds

relief was rudely ended when referee Ken Burns disallowed the effort.

Cherry and Clarke's protests Sunderland surged into concerted attack, ending with quick

fire shots from Tueart and Porterfield. Both were blocked by Madeley,

before Guthrie hammed the ball powerfully just into the side netting with

half the crowd thinking it was inside the post. United, though, were doing more pressing in this half and

Madeley pushed a good ball through for Lorimer, who turned and fired a

fierce shot low into the side netting. They were also denied what seemed a blatant penalty in the

56th minute when Watson looked to have tripped Bremner, but, as Geoffrey

Green noted in The Times, 'Perhaps Bremner's own past told against

him instinctively as the referee dismissed the swift passage with an imperious

wave of the arm.' After 65 minutes came the moment when realisation dawned

on United that this was simply not to be their day. The ball was worked

from Hunter on the left to Giles and then Jones on the edge of the Sunderland

box. His back to goal, he held play up before sliding the ball to Reaney

in the deep. The full-back's lofted cross to the far post found his defensive

colleague Cherry coming in for a full length diving header on the blind

side. Somehow, Montgomery got to it and palmed across the face of goal. Lorimer moved in with a gaping goal in front of him, no

more than five yards out, and struck his shot well and on target. 'And

Lorimer makes it one each!' was the assured summation of BBC commentator

David Coleman. Except he hadn't … Montgomery had scrambled back to his feet and hurled himself

instinctively at the shot, somehow turning it up onto the underside of

his crossbar and out. The prostrate Cherry flicked an involuntary leg

at the ball, as if in mute protest Cherry beat the ground in frustration, Lorimer looked around

in disbelief and a nation held its breath … this was the stuff of dreams.

Or nightmares, in United's case. Peter Lorimer: 'I had so much time that I had the luxury

of thinking to myself, "Right. Don't blast it. It might go over.

Just nice firm contact back into the empty net and we're out of trouble."

I hit it just as I wanted to hit it, sweetly, right off the middle of

my foot. Monty was on the ground and I turned with my arm in the air.

But with a desperate effort the keeper raised himself and somehow the

ball hit his elbow, cannoned onto the underside of the bar, bounced on

the line and was scrambled to safety.' United were not yet ready to surrender, however, and continued

to fight their cause. Kerr had closely shadowed Gray throughout the game and the

off colour United wingman found few chances to shine. But when he did

take one opportunity to do so he made good ground down the left before

his progress was halted by a fine Watson tackle. As time went on with no breakthrough, United's sense of

urgency increased and they began to push more men forward. Cherry was

on almost permanent attack while Madeley took every opportunity to throw

his weight behind the forwards. Giles shot over following a centre from Lorimer and soon

afterwards Clarke got away from the defence but had his shot deflected

wide by a defender. With 15 minutes to go United brought on Yorath for Gray.

He was no match winner, but Revie gambled that his robust determination

would serve Leeds better than Gray's somewhat insipid forays. The Welshman

was involved almost immediately in the move that led to Cherry drawing

another good save from Montgomery as he came in for another diving header

on the blind side. Montgomery was in action again shortly afterwards, this

time when Yorath went through before unleashing an angled shot which the

goalkeeper saw very late. But he recovered well to make a good stop. Then

Hughes was booked for pulling back Cherry when the United full-back had

got the better of him out on the left. United threw everything into attack as the clock ran down

and Madeley had an angled shot stopped on the line. But Sunderland, having

fought so well throughout, were in no mood to surrender their advantage. A foul on Hunter by Porterfield just outside the Sunderland

penalty area raised United's hopes of a last gasp equaliser and when Giles

tossed the ball to Lorimer the United striker's power drive rebounded

off the Sunderland wall. With two minutes remaining and United committed to kitchen

sink aggression, there was a breakaway from Sunderland. They had a four

on two advantage, but it looked like the move had broken down when Tueart

could only find Madeley as he sought to play a killer through ball. But

Hughes robbed the United man to revive the move and Halom, socks rolled

down round his ankles, had two shots from the edge of the Leeds box. Harvey

leaped heroically to turn aside the second and better effort. Sunderland had the ball in the Leeds net deep into injury

time when Halom clumsily barged Harvey over the line, but the effort was

disallowed for a clear infringement. The incident ate up valuable seconds

for Leeds, and they had no time to fashion another opportunity with referee

Burns blowing the final whistle as they sought to come out from the free

kick. On raced Bob Stokoe, raincoat flapping, in a joyous sprint

to embrace his heroic goalkeeper in one of the most memorable moments

in Wembley history. The no hopers had won the Cup and Leeds' ambitions

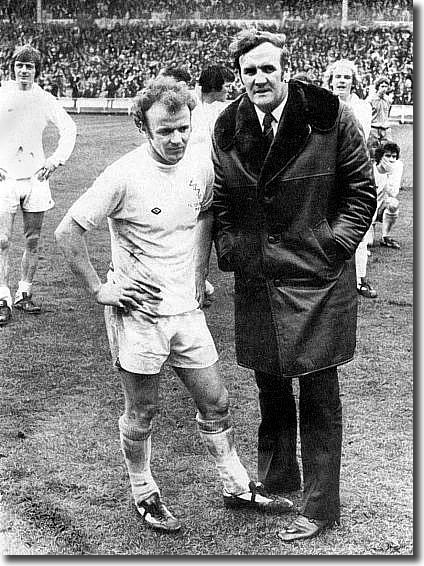

were dead in the water. Leeds had no complaints and few excuses. United manager

Don Revie sportingly conceded that Sunderland had earned their victory.

'Naturally I am extremely disappointed and so are all the boys. We did

not play well in the first half, but I do not want to take anything from

Sunderland. Full credit to them. All their team played well and I give

them 100 per cent marks for their efforts.' Paul Reaney summarised a drab day of disappointment by admitting,

'We weren't Leeds, were we?' Don Warters in the Yorkshire Evening Post: 'United

certainly never played as well as they are capable. They rarely found

the time and space against a hard running Sunderland in the first half

to make much impression on the Second Division side's defence, and though

there was a big improvement after the break it was still United below

their best. 'Hard as skipper Billy Bremner tried to rally his side,

neither he nor Johnny Giles could gain command of midfield. 'Sunderland, playing it just as they were expected to, chased

everything, ran well and determinedly when they had possession and generally

did not allow United any time to settle. Kerr did a first class job in

blotting one of United's potential match winners, Eddie Gray, out of the

game, and former Rotherham player Dave Watson did a magnificent job at

the heart of the Roker Park side's solid defence. He hardly put a foot

wrong and his confidence in the Sunderland rearguard did much to keep

United's forwards at bay, particularly in the second half when Revie's

men stepped up their pressure. 'Even the most ardent supporter of United would surely agree

that this was a day when their side did not reach the usual high standard.

The rhythm of their play was missing, Johnny Giles: 'There was a feeling out there that, by beating

Wolves, we had already won the Cup. And now we would just have to go through

the formalities at Wembley against a Second Division side who were just

happy to be there and to enjoy the occasion. 'The Leeds lads didn't think like that though. We appreciated

the fact that they had good players like Dave Watson, Jim Montgomery and

Dennis Tueart. But most observers felt that we would have too much for

them, and understandably so. Nobody thought this was going to be a great

epic like the final against Chelsea, when we had gained a few admirers

for the quality of our football and the cruelty of our defeat. 'This time, in the minds of everyone, we were clearly the

bad guys, who were going to turn the Cup final into something of a non-event

by hammering little Sunderland. It couldn't be any other way. And, of

course, we did hammer Sunderland on the day. We slaughtered them. We did

everything we could possibly do to them, except one thing - we didn't

score a goal against them. 'They scored a goal against us. And that was that. 'The big moments from that day are known to all - the miracles

performed by Montgomery, the shock of Porterfield's goal, the sight of

Don's old enemy, Bob Stokoe, racing across the pitch at the final whistle

to embrace his keeper. To me, the whole thing still has a horrific quality,

the biggest disappointment of my career. It wasn't one of those horrible

experiences that you might learn something from, except this one thing

- as I watched the Sunderland players going up the steps to collect the

Cup, I finally knew what people meant when they said that something "felt

like a bad dream". 'And we'd had a few of those already. But sometimes when

you lose the League, you don't know you've lost it, on the day. You may

realise six weeks later that that was the moment when you lost it, but

it's not quite the same as standing on the 'In my case, they'd be saying I was past it. For the younger

lads, playing for Leeds in itself would be enough grounds for mockery.

And it continued to feel like a bad dream, which was somehow getting worse

as we sat in the dressing room and Bobby Kerr, the Sunderland captain,

came in with the Cup. 'Bobby wasn't a bad lad, he wasn't trying to rub our noses

in it, but it was still a totally surreal experience as he handed the

FA Cup around to us, so we could take a drink from it. One by one, we

all had a sip of the Sunderland champagne. Nobody told Bobby to f*** off.

Which on a day of miracles was probably the most astonishing of them all. 'And then the scene of this rambling horror story shifts

to the Savoy Hotel, where the Leeds victory dinner was due to take place

- a familiar enough arrangement at this stage, except, this time, there'd

be a lot more than myself and Peter Lorimer at it. All the wives and girlfriends

would have stayed at the hotel on the Friday, and everyone would have

been ready for a fantastic night. If only we could have scored a goal

against Sunderland, just the one. If we had scored one, we would have

scored all day. And then we'd all be looking forward to our big night

at the Savoy, instead of dreading the very thought of it. 'Don was in bits. When everyone had sat down in the banqueting

hall, he stood before us and he tried to make a speech. It was so sad

for a man who was so driven, to have to face this. He started speaking,

but he couldn't do it. He just broke down.' Rob Bagchi and Paul Rogerson in The Unforgiven: 'Watson,

later capped sixty-five times for his country, was the unsung hero of

the occasion, though it is not his name that is remembered. Yet he was

lucky on 10 minutes when a foul on Bremner in the penalty area went unpunished.

Had referee Ken Burns taken Stokoe's entreaties on board? Watson, too,

had a hand in Sunderland's goal, which came on 31 minutes, taking three

United players with him as Billy Hughes curled in a corner from the right,

beyond Leeds' defensive cover. Watson's run caused the sort of carnage

that Jack Charlton had patented

for United. If any team should not have been distracted by it, that team

should have been Leeds, who'd been using the trick for almost a decade.

Over-preparation and Revie's obsession with Watson's aerial potency in

those assiduously devoured dossiers was their undoing, as the defence

was left open to a sucker punch by Watson's clever dummy. 'With an hour to go, and regular chances coming their way

at frequent intervals, Leeds should not have been unduly concerned; but

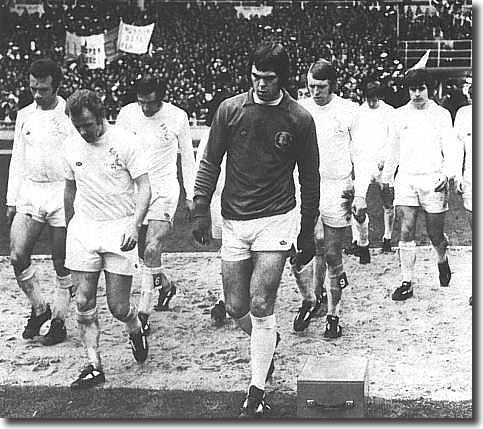

something was patently wrong. As the teams emerged for the second half,

the red and white striped shirts galloped past those in white, eager to

return to the fray. "United players appear to know their fate"

was the caption to a newspaper photograph published the next day of the

Leeds players ambling back on to the field. Of the eight men in shot,

only Peter Lorimer is not staring fixedly at the ground. 'At the final whistle Revie stood rigid in the rain, pain

etched into his face. Stokoe, who had flouted Cup Final protocol by wearing

a red tracksuit, came skipping and jumping onto the 'In the war of words whipped up by Fleet Street in Cup final

week Revie had been hopelessly outgunned and, although the result might

have embarrassed the pundits, it delighted his numerous detractors. Artistic

license was freely issued, the Daily Mail's Vincent Mulchrone being

among the more fanciful observers. "In Sunderland," he wrote,

"there is one job for every forty boys and the thirty-nine stepping

straight from school to the dole queue wrote a sign on the wall begging

the lads to put Sunderland on the map. The lads obliged." One Sunderland

supporter was so overcome with delight that he hurled an armchair through

his front window. When Stokoe's team returned to Sunderland to parade

the Cup, bed-ridden patients at the local hospital demanded to be wheeled

outside so they could salute their heroes. "Leeds, a paradox of arch-professionalism

and high superstition," wrote another scribe, "wilted like men

crushed by divine intervention." 'Commendably, Revie declined the opportunity to vent his

spleen at Stokoe after the game: "The better team won on the day,"

he admitted. However, he would later acknowledge that the result was the

most shattering experience of his career - and by now he had a raft of

them to choose from. In an unaccustomed speech at the post-match banquet

he struck that note of plaintive defiance he habitually adopted under

siege. "It's a bit unusual for me to stand up," he began, "but

I feel our players have done enough in ten years to walk in to your applause,

even without the FA Cup. We never tried to cheat, we tried to be honest,

and I would be less than honest if I did not ask you to salute the most

consistent side that ever lived." 'For some Leeds supporters, however, defeat by Sunderland

was another signal that the long-serving backbone of Revie's team had

reached its sell-by date. Debate raged on the letters page of the local

paper, where several self-consciously heretical correspondents started

to lambast the manager and his team. "The unpalatable truth is that

Leeds had only themselves to blame …" declared one of them, "but

were betrayed by a malady which seems unforgivable. Giles, the midfield

mainspring, is no longer the effortless general and is too easily caught

in possession ... United must hope the much-missed Cooper recaptures his

England form and Don Revie must also consider the claims of Jordan and

the promising Frank Gray."' 5 May 1973, was a momentous day for Leeds United. It caught

them at a low and Sunderland at an irrepressible high, but it was far

more symbolic than that: the determined young men of Revie's Golden Age

had grown into weary, ageing troops and next to the energy, vibrancy and

spirit of Sunderland they looked like shadows of their former selves.

In fact, it felt almost like Sunderland were the new Leeds, callow young

men from the depths of the Second Division, unsettling higher class opponents,

as Revie's kids had done a decade earlier. United were not finished, as some critics gleefully claimed,

and would come again, but on this particular day it felt like their time

had passed. One of the lowest points in the history of Leeds United Football Club

came in early May 1973, as they sought to defend the FA Cup they won

for the first time twelve months earlier. They were the hottest favourites

for years, considered certainties to beat their Second Division opponents,

rank outsiders Sunderland. A day that should have been one of celebration

and triumph ended instead with United in a trough of depression and despair.

One of the lowest points in the history of Leeds United Football Club

came in early May 1973, as they sought to defend the FA Cup they won

for the first time twelve months earlier. They were the hottest favourites

for years, considered certainties to beat their Second Division opponents,

rank outsiders Sunderland. A day that should have been one of celebration

and triumph ended instead with United in a trough of depression and despair. few

minutes can seem like hours …

few

minutes can seem like hours … determined

to extract every last ounce of enjoyment from an occasion they can never

have expected to grace. Moreover, with United in purdah Bob Stokoe had

free rein to begin an unsubtle but effective bout of psychological warfare

against his opposite number. His first outburst was the usual nonsense

about the allocation of "England's dressing room", which had

gone to United, and the matter of having the Leeds fans at the tunnel

end, where the teams would enter the stadium. The latter complaint was

especially meretricious. Stokoe knew full well that 81,000 of the 100,000

crowd - the Sunderland supporters and 62,000 "neutrals" - would

be rooting for his team.

determined

to extract every last ounce of enjoyment from an occasion they can never

have expected to grace. Moreover, with United in purdah Bob Stokoe had

free rein to begin an unsubtle but effective bout of psychological warfare

against his opposite number. His first outburst was the usual nonsense

about the allocation of "England's dressing room", which had

gone to United, and the matter of having the Leeds fans at the tunnel

end, where the teams would enter the stadium. The latter complaint was

especially meretricious. Stokoe knew full well that 81,000 of the 100,000

crowd - the Sunderland supporters and 62,000 "neutrals" - would

be rooting for his team. even allowed the cameras on to the team coach, something then unprecedented.

In the tunnel Sunderland wore their cares as lightly as Leeds were tense

and preoccupied. "When we came out the noise was like being hit in

the face by a sledgehammer," Dave Watson remembered. "All the

neutrals seemed to be backing us. Again, that seemed to get to Leeds."'

even allowed the cameras on to the team coach, something then unprecedented.

In the tunnel Sunderland wore their cares as lightly as Leeds were tense

and preoccupied. "When we came out the noise was like being hit in

the face by a sledgehammer," Dave Watson remembered. "All the

neutrals seemed to be backing us. Again, that seemed to get to Leeds."' both. The ball dropped to Eddie Gray, who blazed it

wide with his weaker right foot.

both. The ball dropped to Eddie Gray, who blazed it

wide with his weaker right foot. in space in the centre of

the area. He cushioned it on his thigh and stroked a lovely volley goalwards.

It was down the throat of Harvey, but the effort was simply too true and

at too close a range to be denied. As if in symbolic surrender, Harvey

was rooted with upraised arms and hands as the shot clipped Clarke's shoulder

on its way and the keeper could do nothing bar touch the ball up into

the roof of his net.

in space in the centre of

the area. He cushioned it on his thigh and stroked a lovely volley goalwards.

It was down the throat of Harvey, but the effort was simply too true and

at too close a range to be denied. As if in symbolic surrender, Harvey

was rooted with upraised arms and hands as the shot clipped Clarke's shoulder

on its way and the keeper could do nothing bar touch the ball up into

the roof of his net. against the decision held little conviction.

against the decision held little conviction. at the lack of justice, but it ran

away to be cleared.

at the lack of justice, but it ran

away to be cleared. yet it was also a day when the breaks went against them.'

yet it was also a day when the breaks went against them.' pitch at Wembley looking at Second Division Sunderland receiving the Cup,

realising that it's actually happening to you right at that moment, and

knowing what's in front of you - all the jeering, the gloating, the demolition.

pitch at Wembley looking at Second Division Sunderland receiving the Cup,

realising that it's actually happening to you right at that moment, and

knowing what's in front of you - all the jeering, the gloating, the demolition. pitch to hug his match-winning goalkeeper. Grace in victory was not in

the script. "I hadn't a lucky suit like Don Revie," he jibed,

"so I just came as one of the lads."

pitch to hug his match-winning goalkeeper. Grace in victory was not in

the script. "I hadn't a lucky suit like Don Revie," he jibed,

"so I just came as one of the lads."