|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Second Division - Elland Road - 14,000

Scorers: None

Leeds City: Bromage, D Murray, Clark, Hargraves, Walker, Henderson, Parnell, Watson, D Wilson, Lavery, Singleton

Burnley: Green, Barron, Dixon, Cretney, Cawthorne, Moffat, Kenyon, Whittaker, R Smith, A Bell, A Smith

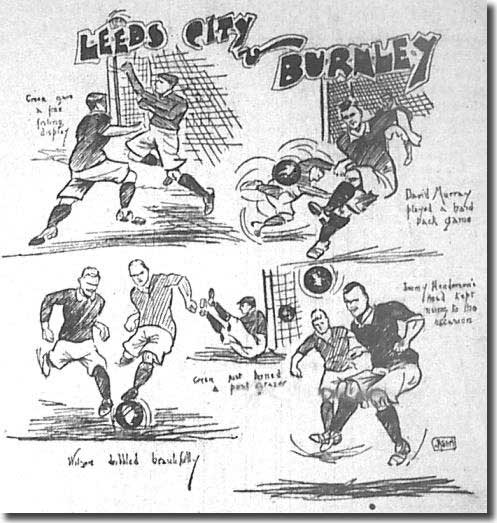

Leeds City's game with Burnley at Elland Road on 27 October 1906 was

the most momentous in the club's short history to that time. It City had just started getting their act together on the field after a

pretty dismal opening run. Three victories on the bounce, their first

of the season, had seen the team drag themselves up from 16th spot to

8th, seemingly ready to mount a genuine challenge for promotion from the

Second Division after a promising debut season when they had finished

sixth. Their Lancastrian visitors were level on points with City, but lay two

places higher on goal average. A fourth win for the Peacocks would have

seen them on the cusp of the promotion places. The Elland Road Selection Committee seemed to have finally settled on

their best eleven after being heavily criticised by club supporters earlier

in the season for continual chopping and changing - nine of the men who

faced Burnley had figured in each of the three preceding games. The exceptions were former Plymouth Argyle left-back Andy

Clark, returning after missing his first game of the campaign the

week before (a 2-1 victory at Port Vale), and James

Henderson, making his bow for the season in place of Jimmy Kennedy

at left-half. There had been a heavy storm the previous evening, but the newly installed

drainage system had done its job and left the turf in decent enough condition. Leeds City had the best of things in the first half and, according to

the Yorkshire Post, 'were almost incessantly attacking during the

first half, and there was some remarkably clever football by the whole

of the front line, though the Watson-Parnell

wing was the most prominent. The final onslaught on the Burnley goal was

never quite as deadly as the general plan of attack was fast and clever,

and for this reason, as well as Green's cool goalkeeping, no substantial

reward in points resulted. Wilson twice skimmed the bar with fast drives

after receiving from his wings, but generally the luck was against the

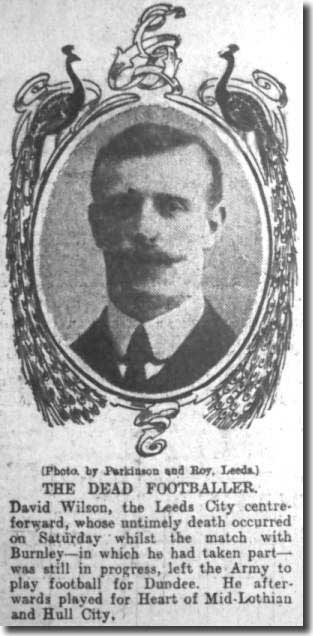

home side, and at the interval no points had been scored by either side.' The Wilson in question was David

'Soldier' Wilson, a powerful and committed centre-forward of Scottish

extraction, who had joined City from Hull the previous December for £150,

ending up top scorer with 13 goals from his 15 appearances. He could have

been sold at a quick profit but the City directors recognised his worth

and refused to sanction a move, although they received several offers

in excess of £500. A knee injury had restricted Wilson's appearances in

the current campaign and he had yet to trouble the scorers. Wilson was struggling to recover his best form, but had

done enough in the first half to signify that he could yet have an impact

on the outcome of the game, even though he had been winded by a clash

with two Burnley defenders and was not feeling fully himself. During the

break 'he expressed confidence that the team would just pull through.' Challenges became more robust after the interval and, according to the

Leeds Mercury, 'some of the players were guilty of Shortly after that, Wilson headed the ball goalwards and the effort seemed

to cause some sort of injury, for around the hour mark he was forced to

withdraw to the dressing rooms. He looked very pale and in great pain,

telling the club trainer George Swift

that 'he felt a heavy pain in his chest' but that he had not 'been charged

or fouled in any way, and could only think he must have strained himself

internally in jumping up to head the ball into the net'. With Wilson absent and the indisposed Lavery little more than a passenger,

Burnley started to get back into the game. Whittaker and Kenyon, the Lancashire

team's right wing pairing, twice came close to breaking the deadlock,

although City maintained their full share of the play. Things took a further turn for the worse when Harry

Singleton also sustained an injury. He remained on the field for a

while, but had to admit defeat and withdraw with fifteen minutes remaining

after another stiff challenge. Singleton's exit was the catalyst for the day's tragic conclusion. Soldier

Wilson was renowned for his bravery and commitment, and could not stand

idly by when he heard the news that his team were virtually down to eight

men. He screwed up his courage and decided to enter the fray once more,

despite the stringent advice of club doctors and officials. The Yorkshire

Evening Post: 'Though his chest was very sore, Wilson said he could

not remain there while the Leeds City team were in such straits. So, although

many of those in the room endeavoured to dissuade him from his purpose

he went out to resume play, his reappearance being greeted by a storm

of cheers.' It was quickly evident, however, that Wilson was neither use nor ornament

and that he was in no fit state to continue for long. His return had been

foolhardy in the extreme and, after three minutes and a single failed

attempt to play the ball, he withdrew once more, clearly in the most extreme

agony. There were only minutes left and still no score. Even though they were

in effect three men down and facing an uphill fight, it seemed However, the result was of little import at Elland Road. A rumour of

desperate tragedy was doing the rounds among the crowd, and a shock was

waiting for the City players when they reached the dressing room - David

Wilson had lost his life seconds before the end of the game. The sensational news spread around the city like wildfire. When Wilson had first left the field, police constable John Byrom, on

duty at the players' gate, was so concerned at the player's demeanour

that he followed him down to the dressing rooms. He found him writhing

in evident pain on the ground with chest pains. The policeman summoned

help, and was soon joined by three doctors, Dr Earnest Frederick Taylor,

the City Club's physician, Dr Fawcett, who was sitting in the stand, and

Dr Whittaker, the Burnley party's physician. Wilson was suffering intense

pain in the chest, neck and left arm. He was carried into the directors'

room, where Dr Taylor could find nothing definite to account for his condition,

although he assumed that he had had a heart attack. Dr Taylor: 'I thought

he was far too ill to ever think of returning to the field.' Eventually Wilson's condition started to stabilise and he felt a little

better. His wife, who had been in the stand, had driven off in distress

when Wilson had first been injured, and a cab was called to take him home.

However, when Wilson heard of the injuries to the other players, even

though his chest was still very painful, he insisted on going back out

onto the field. The doctors and club officials tried to dissuade him,

but Wilson would have none of it - he walked out of the room and returned

to the fray. According to PC Byrom: 'Five minutes later, he came off a second time.

I assisted him to the dressing room, and helped him to undress. He said

he would have a hot bath, but all at once after getting into the bath

he laid down and started kicking his legs violently. I took hold of him

and held his head out of the water, but he seemed to lose consciousness,

and never spoke again.' The officer, with the assistance of trainer George Swift, lifted Wilson

out of the bath and placed him on a table, where, in spite of the immediate

attention of Dr Taylor, he died within seconds. It was an immense shock to all present. Before the players left the dressing

rooms Wilson had appeared to be in good health, and told the club's secretary-manager

Gilbert Gillies that he felt perfectly fit. According to his wife, Wilson

had never seriously complained of ill health, although once or twice during

the past few weeks he had complained of being short of breath. Mrs Wilson

suggested that her husband smoked too much: 'He was a heavy smoker of

cigarettes, and I kept telling him they were the cause.' Wilson's body was taken by ambulance to the couple's house at 8 Catherine

Grove, Beeston Hill and their relatives, who lived in Leith, were telegraphed,

arriving the next day. On Tuesday morning a post mortem was held, together with an inquest,

as reported by the Yorkshire Evening Post: 'The inquest was held

at 'It was this same brother, by the by, who was in such a terrible state

of anxiety and uncertainty yesterday, as to whether it really was his

brother David who was dead. "Is it David Wilson, late of the Hearts

of Midlothian, who is killed?" he wired to Mr Gillies, but before

Mr Gillies' reply reached him his suspicions had been confirmed, and he

was on his way to Leeds.' The inquest determined that it was 'over eagerness to be of service to

his club that was Wilson's undoing. The doctor who was in attendance upon

him at the last expressed the emphatic opinion that the fact of going

on to the field a second time caused Wilson's death - that, in a word,

if he had remained in the directors' room he would have had a good chance

of getting better. 'The actual cause of death was angina pectoris, a medical term which

signifies what is more commonly known as heart anguish; and the jury at

today's inquest certified that Wilson had died from "heart failure,

from over exertion in a football match".' On the Wednesday morning, City directors and players met at Catherine

Grove for a service held by Reverend Mr Price, then went up by train from

North Eastern Station to the funeral in Leith. Leeds City paid for the

funeral and arranged a benefit match a few weeks later against Hull City

for Wilson's widow and their ten-month-old baby girl. It came as a surprise to many who knew him that Wilson was only 23-years-old,

having been born in the East of Scotland on July 23, 1883. Most people

who saw him would have taken him to be about 30, because of his heavy

fair moustache. He was one of three brothers who made their name as footballers in the

Army, and this led him to be familiarly known as Soldier Wilson. The Yorkshire

Evening Post: 'Wilson had had an interesting football career, the

story of which he related to the writer only a few months ago. He was

a native of Musselburgh, in the county of Midlothian, and in 1896 enlisted

in the Cameron Highlanders, with whom he went out to Gibraltar, where

he began playing Association football. Whilst at Gibraltar, Wilson transferred

to the 1st Battalion Black Watch, which regiment he accompanied to India,

and subsequently to South Africa, where, with Colonel Remington's column,

he took part in some of the Boer drives. 'It was after returning to England that he was bought out of the army

by the Dundee Club, for whom for a season or two he played at centre-forward

in the Scottish First League. Just two years ago he had his knee badly

twisted, and on his recovery he was transferred to the Hearts of Midlothian

Club, for whom he rendered yeoman service until joining Hull City. He

played at Anlaby Road in two or three matches last season, and then came

to Leeds City, the transfer fee paid for him being £150.' Many felt that Wilson had lost his form, but City secretary-manager Gilbert

Gillies retorted 'Those critics did not know Wilson. There were few better

centre-forwards in the country.' The demise of David Wilson is one of the greatest tragedies in the history

of Leeds City, but led directly to the arrival of the club's most celebrated

son. On 18 November, the Peacocks paid £350 to Lincoln City to secure

the services of Billy McLeod, a centre-forward who was even more productive

in front of goal than his predecessor. Over the 14 years that followed,

McLeod was to score a phenomenal 171 goals in 289 League games for the

club. The contributions of McLeod, however, were a future phenomenon. At the

start of November 1906, everyone connected with Elland Road was in a trough

of despair at the loss of a trusted and worthy colleague. David Wilson

would be sorely missed and his death left a shadow over the club. was

memorable for the most tragic of reasons: the contest was marred by one

of the earliest recorded deaths of a football player during a first-class

match.

was

memorable for the most tragic of reasons: the contest was marred by one

of the earliest recorded deaths of a football player during a first-class

match. tactics which, to say the least, were of too vigorous a character. Lavery

and Singleton were working nicely towards the Burnley goal when Lavery

was tripped from behind, and fell heavily on his head. The little inside-left

was stunned, and it was several minutes before he was brought round. The

incident called for stern action by the referee, but that official only

cautioned the offending Burnley player, when even Burnley officials on

the stand were agreed that the culprit should have been sent off. Lavery

was almost quite useless after this, so that Leeds were practically playing

with ten men.'

tactics which, to say the least, were of too vigorous a character. Lavery

and Singleton were working nicely towards the Burnley goal when Lavery

was tripped from behind, and fell heavily on his head. The little inside-left

was stunned, and it was several minutes before he was brought round. The

incident called for stern action by the referee, but that official only

cautioned the offending Burnley player, when even Burnley officials on

the stand were agreed that the culprit should have been sent off. Lavery

was almost quite useless after this, so that Leeds were practically playing

with ten men.' that

Leeds City would be able to hold out for the goalless draw that their

pluck had merited as David Murray and goalkeeper Harry

Bromage performed wonders in keeping the Lancastrians at bay. It was

not to be, however, and in the closing seconds Bell, the Burnley inside-left,

received the ball from a free kick and steered his shot beyond Bromage

to settle the game.

that

Leeds City would be able to hold out for the goalless draw that their

pluck had merited as David Murray and goalkeeper Harry

Bromage performed wonders in keeping the Lancastrians at bay. It was

not to be, however, and in the closing seconds Bell, the Burnley inside-left,

received the ball from a free kick and steered his shot beyond Bromage

to settle the game. the Imperial Hotel, Beeston, before the City Coroner (Mr J C Malcolm).

There were present at the inquiry Messrs R Younger, Dimery, A Eagle and

J Oliver (directors of the Leeds City Club), Mr Clayton (financial secretary)

and Mr Gillies (the secretary and manager). Amongst those present were

some of the deceased's relatives, including an uncle, who brought him

up as a child, and a brother - a manly young fellow from the Black Watch,

the deceased's old regiment, who, in his Highland uniform, was a sad auditor

of the proceedings.

the Imperial Hotel, Beeston, before the City Coroner (Mr J C Malcolm).

There were present at the inquiry Messrs R Younger, Dimery, A Eagle and

J Oliver (directors of the Leeds City Club), Mr Clayton (financial secretary)

and Mr Gillies (the secretary and manager). Amongst those present were

some of the deceased's relatives, including an uncle, who brought him

up as a child, and a brother - a manly young fellow from the Black Watch,

the deceased's old regiment, who, in his Highland uniform, was a sad auditor

of the proceedings.