Part 1 Pacesetters - Part

2 The Leeds United trial - Part 3 A season

falls apart - Results and table

Leeds United Football Club experienced an extraordinary close season

in 2002, during which the lack of success in the previous season cost

their manager his job, and a big name successor replaced him. The story

is told in two major features by The Sunday Times.

David Walsh: How O'Leary lost the plot

As David O'Leary drove his silver Mercedes from his home in Harrogate

last Thursday morning, he believed it was just another day at the office.

An 11 o'clock meeting with club chairman Peter Ridsdale at Elland Road,

a few other loose ends to tie up, and the next day he and his wife, Joy,

would be on their way to Sardinia. Two weeks when the world of football

could go to hell.

If there was one quality that defined O'Leary's life in the game, it

was an ability to dodge the bullets. He survived 20 years as a player

at Arsenal, and though management had been more precarious, he had come

through. Didn't he always? 722 first-team games for Arsenal: know what

that takes? Things at Leeds, though, were not good. Only two days earlier

he had met Dick Wright at the training ground at Thorp Arch. Wright worked

for the club's media department.

'Morning, Dick, how are things?' 'Haven't you heard?' 'Heard what?' 'I've

been made redundant. Finished two weeks ago. I'm in to collect some things.'

Wright had worked for eight years at Leeds. O'Leary offered his sympathy

and carried on. Poor Dick; nobody was safe any more.

What could the chairman want? Something about Rio, probably. O'Leary

had suggested the club should not sell Rio Ferdinand, and the plc was

getting touchy about any hint of dissent. If this was Ridsdale's problem,

he would argue that his comments were only going to push up Rio's price.

Surely the chairman would understand that. People didn't realise how many

balls a manager had to juggle.

As his Mercedes headed for Elland Road, the sky was blue and the sun

was shining: so brightly that O'Leary never saw the train coming. And

was it travelling! There was no preamble, no small talk. Ridsdale simply

told O'Leary of the board's decision to fire him. There were no tears,

no histrionics; just the brutal reality of dismissal  and

a vague agreement to present the decision as an agreed separation. Ridsdale

said he would speak to O'Leary's adviser, Michael Kennedy, about compensation.

and

a vague agreement to present the decision as an agreed separation. Ridsdale

said he would speak to O'Leary's adviser, Michael Kennedy, about compensation.

O'Leary had once described Ridsdale as 'the best chairman in the game';

Ridsdale had called O'Leary 'the best young manager in the Premiership'.

Like so much of what was said at Leeds over the past three seasons, the

compliments were written in sand. Now two men, who could have talked for

their respective countries, had nothing to say.

Less than three minutes after entering, O'Leary left Ridsdale's office.

Leeds issued a statement saying their manager had departed from the club

'by mutual consent'. Ridsdale then telephoned Kennedy and briefed him

on what had taken place.

'What do you mean, "mutual consent?",' asked Kennedy. 'You

sacked David.'

'But the statement has already been released.'

'Well, you're going to have put out another statement,' said Kennedy.

back to top

Leeds issued a second statement, this time telling what had truly taken

place. The first shots in the battle for compensation had been fired.

On the way back to Harrogate, O'Leary stopped off at the club's training

ground near Wetherby, cleared his office and said his goodbyes. Sad day,

but that's how it goes. The man who was bullet-proof had taken the biggest

hit of his football life.

In charting his subsequent fall, there is a piece of advice he offered

to his players that could now be inscribed on his own tombstone. 'The

sad thing in football today,' he said more than three years ago, 'is that

people who earn a lot think they have to change. They get arrogant, even

though they've done nothing. They lose touch with their friends and inherit

the so-called 'in people'. In-crap. These people, I wouldn't call them

friends, they like you for what you are today but tomorrow they'll drop

you.'

But it was O'Leary himself who seemed most vulnerable to the temptations

he warned his players about. When he went to the US Open at Southern Hills

Country Club, he travelled with Lee Westwood. At the Formula One grand

prix in Monaco, he fraternised with Eddie Jordan. He spoke also of his

close friendship with Leeds's deputy chairman and most influential director,

Allan Leighton. But without realising it, O'Leary was losing the respect

of those who could have saved his skin - his own players.

The difficulties came with defeats. Prepared to accept credit when things

were going well, the manager couldn't stop himself publicly criticising

players on the bad days. Woodgate was castigated for a performance against

Leicester in December 2000; Smith was often scolded for a lack of discipline,

Harry Kewell for lack of form. Mills, too, got the treatment.

At first, there were pockets of disaffection. Respected senior players

and former England internationals, Batty and Jason Wilcox, were not impressed.

The disaffection spread until it was rampant. Even a player as easy to

manage and as much in love with the game as Gary Kelly became demoralised

under O'Leary. It was clear, too, that Kewell had lost his zest for the

game.

What the players saw was a manager who said one thing and did another.

At the end of the Woodgate/Bowyer trial, he warned them against speaking

publicly. Not a word, he said. The chairman would speak for the club.

That was Saturday morning. On the very next day, the News of the World

carried exclusive extracts from O'Leary's book, Leeds United  On

Trial, and the Sunday People carried O'Leary's exclusive column.

Both contributions were given over to the trial of Woodgate and Bowyer.

For both, O'Leary was paid.

On

Trial, and the Sunday People carried O'Leary's exclusive column.

Both contributions were given over to the trial of Woodgate and Bowyer.

For both, O'Leary was paid.

Other inconsistencies were noted. O'Leary spoke about the need for discipline

but was unconvincing when it came to dealing with outbreaks of indiscipline.

The players wondered what would happen when the substituted Robbie Keane

was caught on camera mouthing 'f***ing w***er' at his manager as he walked

from the pitch. Next day at training, O'Leary told Keane that with so

many cameras at games, he needed to be more careful.

Towards the end of the season, tension between O'Leary and Mills manifested

itself in a fierce training-ground row. Such was the ferocity of the full-back's

reaction to O'Leary's criticism, that the players expected Mills to face

disciplinary action. Instead, the manager tried to placate him.

When O'Leary complained publicly about big-name players not performing,

they remembered that when they were training at Thorp Arch on the day

before the home game with Arsenal, he was in Dublin signing copies of

Leeds United On Trial. He could say what he liked in public, but

they knew what was happening in private. Towards the end of the season,

Dacourt said: 'If I play for the reserves on Thursday, I am not going

to play for the first-team on Sunday.' He got the weekend off.

In the circumstances, it was no surprise the team under performed. Fifth

in the Premiership was wretched for a team that had cost £66m to bring

together. Failure to qualify for the Champions' League was catastrophic

for the plc that Leeds had become. Non-executive directors Leighton and

Richard North began to look more closely at the running of the club and

they were unnerved by what they found. They discovered the relationship

between Ridsdale and O'Leary had broken down, they sensed disharmony between

O'Leary and his players, and they decided something had to be done.

The initial plan was to give the chairman and manager the first two months

of the new season to improve things, but events overtook that strategy.

Now watching more closely, the board was annoyed by O'Leary's criticism

of Mills in his Sunday People column. At the World Cup, Mills could

be a liability, said O'Leary.

Asked for his reaction, Mills was measured but damning. Sir Alex Ferguson

and Arsène Wenger, he said, made their criticisms in-house. Elaborating,

he asked: 'Would anyone be happy if the boss walked into the middle of

the office and had a go?' Referring to a specific criticism that O'Leary

had made of the Leeds team, Mills said: 'Sometimes saying the hunger has

gone is an easy way to paper over the cracks. Sometimes you have to look

deeper.'

back to top

By the time the World Cup began, the Leeds board was doing just that.

Such was the growing disunity, the directors felt change could not be

stalled until early in the new season. They were helped by O'Leary's failure

to recognise the perilous nature of his own position. Advised by Ridsdale

that he should toe the company line on any proposed transfers, the manager

went public and said he was against selling the team's principal asset,

Ferdinand.

That act of minor defiance cut the final thread that held the sword over

O'Leary. It was not the reason he was fired, rather it was an excuse to

get rid of him. Before Ridsdale delivered the board's verdict on Thursday

morning, Leeds had sounded out Celtic about Martin O'Neill's availability

and made other enquiries about the possibility of Ireland manager Mick

McCarthy accepting the job.

In Japan, David Beckham and Paul Scholes talked to Ferdinand of how life

at Old Trafford was good. Leeds are adamant that Ferdinand will not leave.

Inside the club, it is speculated that the £35m Leeds need to ease financial

pressures will be raised through the transfers of Dacourt, Bowyer, Keane,

Kelly and Ian Harte.

O'Neill remains Leeds's first choice, but they are unlikely to prise

him away from Celtic Park. A source close to O'Neill insists he will not

take the job. From the moment he was sacked, O'Leary sensed Leeds had

already agreed to replace him with McCarthy. This is far from certain,

and Middlesbrough's Steve McClaren may yet emerge as a candidate. O'Leary

believed McCarthy's friendship with Leeds's media director, David Walker,

could help his case.

It was Walker who ghost-wrote Leeds United On Trial for O'Leary,

and it seemed that their friendship would endure. There is now no guarantee

of that. Not surprisingly, O'Leary has changed his opinion of Ridsdale.

Another casualty has been the once-admired Leighton, who was a key player

in the ending of a beautiful affair.

It would be easy for O'Leary to blame his former friends. He took Leeds

from dull, mid-table anonymity to within touching distance of glory; then,

after the first setback, he got the sack. But the deposed manager should

not blame anybody else. Rather he should recall the words of his old sparring

partner, Mills: 'It is easy to paper over the cracks. Sometimes you have

to look deeper.'

O'Leary has never been a bad fellow. In the end he just could not see

there was a bullet with his name on it. The £1m-plus compensation will

help his recovery, and after his family holiday he intends to try to get

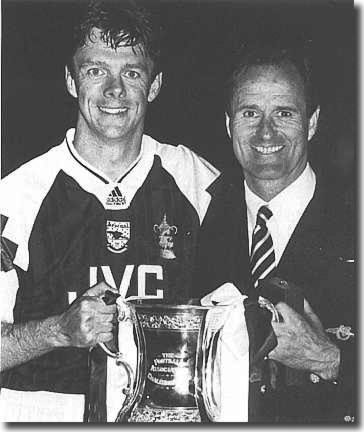

back into football. He was 15 when  he

left Dublin and returned to London. For 29 years, football has been all

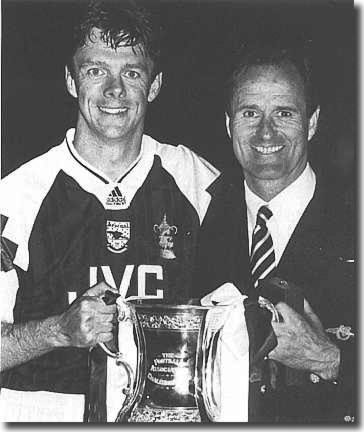

that he has known. As a player, he won two championship medals, two FA

Cup medals, two League Cup medals and 67 international caps for Ireland.

When he passed Geordie Armstrong's coveted record of 621 appearances for

Arsenal, his wife, Joy, asked what he would do next. 'Break 700,' he said.

He did. As an individual player, he could control his life. He never understood

how different management would be.

he

left Dublin and returned to London. For 29 years, football has been all

that he has known. As a player, he won two championship medals, two FA

Cup medals, two League Cup medals and 67 international caps for Ireland.

When he passed Geordie Armstrong's coveted record of 621 appearances for

Arsenal, his wife, Joy, asked what he would do next. 'Break 700,' he said.

He did. As an individual player, he could control his life. He never understood

how different management would be.

O'Leary once talked about a golfing trip in Ireland where he would play

with his son John, dad Christy and brother Pierce. Just the four of them:

he and Pierce against John and the lad's granddad. He can now find more

time to spend with his immediate family. The breathing space offered by

unemployment could be what he needs. For it would be a time to work out

where it all went wrong. But like all former managers, he will be conscious

of the danger of being out of the game for too long.

The greater danger is that he will come back too soon.

Following the departure of O'Leary there were several days of media speculation

over who would replace the Irishman, with Celtic manager Martin O'Neill

thought to head up a short list of three which also included World Cup

managers Mick McCarthy of Ireland and South Korea's Guus Hiddink. Middlesbrough

boss Steve McClaren was also reported to be ready to be installed, but

in the end it was an outside bet who became the new incumbent in the manager's

office.

Hugh McIlvanney of the Sunday Times on 14 July:

Return of the Messiah

It seems to be the professional destiny of Terry Venables to cut a far

larger figure in the lore of football than in its record books. Many of

us who admire his unquestionable gifts as a coach, and feel they are unfairly

represented by the brief list of practical achievements against his name,

naturally have hopes that he will be able to adjust the balance during

the managerial contract he has just entered with Leeds United. But the

continuing effects of the recent turmoil at Elland Road should discourage

towering expectations. Rather than a glorious late chapter, we would perhaps

be more realistic if we anticipated a spirited, characteristically entertaining

postscript to his career.

Of course, though Venables will turn 60 halfway through the first season

of the two-year tenure he has agreed with Leeds, it may be premature to

see his spell there as the last major assignment he will undertake in

football. Now that he has rediscovered his appetite for first-hand involvement,

the hunger could conceivably persist beyond whatever happens in Yorkshire.

There is, however, a clear sense that this will probably be his final

opportunity to thrust himself into the trophy-winning elite of Premiership

managers (he won a Second Division title with Crystal Palace in 1979 and

his FA Cup triumph with Tottenham came in 1991, before today's top league

was formed).

back to top

Age can hardly be considered a handicap at a time when appreciation of

hard-earned experience is reflected in the conspicuous maturity of the

men in charge of clubs who have lately been leading contenders for domestic

honours. Arsène Wenger at Arsenal and Gerard Houllier at Liverpool are

both in their fifties, Sir Alex Ferguson did not let the passing of his

60th birthday dissuade him from extending his reign at Old Trafford and

Sir Bobby Robson, at 69, shows no sign of any waning of his zest for managing

Newcastle United. The years sit lightly on Venables, as is certain to

be demonstrated at Leeds by his infectiously enthusiastic presence on

the training ground. It is not his age but how he has led his football

life that may make the new challenge  particularly

demanding for him.

particularly

demanding for him.

His career has been nomadic, littered with comparatively short-term engagements

and punctuated by sporadic diversions into other areas of interest, from

fiction writing to club owning, to television punditry and various versions

of often ill-fated entrepreneurialism. Nobody should be foolish enough

to deny that, running through these diverse strands of activity, there

has been a powerful commitment to the world he knows best. He has never,

for a moment, ceased to be an out-and-out football man. But the flirtations

and infatuations have suggested a reluctance to marry his substantial

talents totally to the game.

What should be regarded as a given is that he will bring genuine inspirational

qualities to the task of reviving the Leeds squad's combative vigour and

belief in themselves in the wake of David O'Leary's disruptive departure.

There is a distasteful eagerness among Venables' more insistent critics

to try to twist the lack of big-occasion accomplishments on his CV, and

the discreditable baggage accumulated by his commercial ducking and diving,

into a case for declaring counterfeit his huge reputation as a coach.

They are spitting their venom into the wind. All the professionals who

have worked closely with him, and they cover a wide spectrum of generations

and backgrounds, come together in a unanimous salute to the creativity

and effectiveness of his instructional and nurturing skills.

Their testimony tells us he has a deep understanding of the traditional

imperatives of football (as opposed to the jargon-laden theories that

impersonate profundity among less valid practitioners) and consistently

enriches it with original, innovative tactical thinking and a cunning

eye for specific ploys that will unhinge the opposition.

Confronted with so much eulogising from players and coaches who express

gratitude for his improving influence, it is scarcely appropriate for

a reporter to toss in his tiny endorsement, but countless conversations

with some of the liveliest minds ever focused on football in Britain at

least entitle me to imagine I can recognise the right stuff when I hear

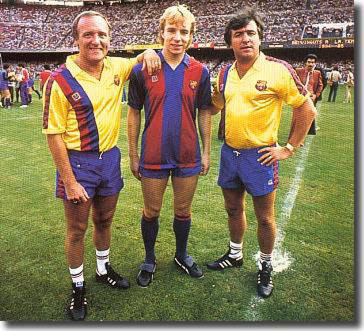

it. And I heard it for sure throughout two or three hours spent one-to-one

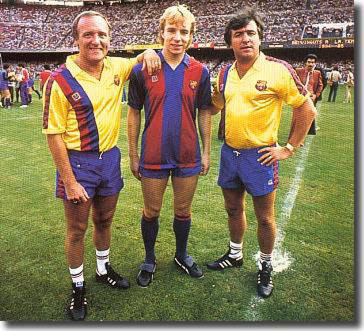

with Venables in a Barcelona hotel in the mid-Eighties (his feat of taking

the great Catalan club to their first Spanish championship for 11 years

in 1985, and then on to a European Cup final, is still his supreme achievement).

When we parted that day, I felt, accents apart, as if I might almost have

been talking to Jock Stein. There is no higher compliment I can pay.

The most virulent of Venables' denigrators use words that are liable

to send a shudder through anybody who hasn't met him. To me, their picture is a bitter, indefensible distortion. I like him a great deal. More to

the point, he has effortlessly kept the friendship and esteem over 40-odd

years of men whose solidity of character and all-round integrity make

me count it a privilege to know them. So, for all the worries about his

conduct of his financial affairs, in terms of human relationships he plainly

has quite a lot going for him.

is a bitter, indefensible distortion. I like him a great deal. More to

the point, he has effortlessly kept the friendship and esteem over 40-odd

years of men whose solidity of character and all-round integrity make

me count it a privilege to know them. So, for all the worries about his

conduct of his financial affairs, in terms of human relationships he plainly

has quite a lot going for him.

back to top

But can he lift Leeds into real, to-the-wire contention for the league

title? Anything less could not be seen as improvement on O'Leary's regime,

during which they finished fourth, third, fourth and then (amid last season's

gathering problems) fifth in the Premiership, and reached the semi-finals

of both the UEFA Cup and the European Cup. The notion that Venables merely

has to take over the baton and quicken the club's stride is ridiculously

simplistic, as is the suggestion that he can instantly advance his cause

by recapturing the faith of the dressing room that his predecessor so

crucially lost. For a start, there is alarming uncertainty about who will

be in the dressing room. Lee Bowyer is poised to move to Liverpool, there

is a widespread assumption that Olivier Dacourt will join Juventus and

a meeting scheduled for today with Rio Ferdinand, the centre back who

could reasonably be designated the most exciting young footballer in the

country, threatens to result in a transfer request meant to facilitate

relocation at Manchester United. The incoming manager may find that his

immediate concern is to avoid losing ground rather than seeking confidently

to gain it.

His endeavours are bound to be inhibited by the harsh lessons about budgeting

that have had to be absorbed at Elland Road. Leeds's monetary affairs

have apparently been irrationally affected in the past by a willingness

to gamble beyond their means on qualifying for the bonanza provided by

the Champions League. Stricter monitoring of expenditure on players will

reduce flexibility when he turns his thoughts to recruiting personnel

capable of reinforcing the squad to emphasise his own priorities on the

pitch. Venables will have to produce something thoroughly remarkable if

he is to free himself from the predicament of being richer in golden opinions

than in silverware.

Part 1 Pacesetters - Part

2 The Leeds United trial - Part 3 A season

falls apart - Results and table

and

a vague agreement to present the decision as an agreed separation. Ridsdale

said he would speak to O'Leary's adviser, Michael Kennedy, about compensation.

and

a vague agreement to present the decision as an agreed separation. Ridsdale

said he would speak to O'Leary's adviser, Michael Kennedy, about compensation. On

Trial, and the Sunday People carried O'Leary's exclusive column.

Both contributions were given over to the trial of Woodgate and Bowyer.

For both, O'Leary was paid.

On

Trial, and the Sunday People carried O'Leary's exclusive column.

Both contributions were given over to the trial of Woodgate and Bowyer.

For both, O'Leary was paid. he

left Dublin and returned to London. For 29 years, football has been all

that he has known. As a player, he won two championship medals, two FA

Cup medals, two League Cup medals and 67 international caps for Ireland.

When he passed Geordie Armstrong's coveted record of 621 appearances for

Arsenal, his wife, Joy, asked what he would do next. 'Break 700,' he said.

He did. As an individual player, he could control his life. He never understood

how different management would be.

he

left Dublin and returned to London. For 29 years, football has been all

that he has known. As a player, he won two championship medals, two FA

Cup medals, two League Cup medals and 67 international caps for Ireland.

When he passed Geordie Armstrong's coveted record of 621 appearances for

Arsenal, his wife, Joy, asked what he would do next. 'Break 700,' he said.

He did. As an individual player, he could control his life. He never understood

how different management would be. particularly

demanding for him.

particularly

demanding for him. is a bitter, indefensible distortion. I like him a great deal. More to

the point, he has effortlessly kept the friendship and esteem over 40-odd

years of men whose solidity of character and all-round integrity make

me count it a privilege to know them. So, for all the worries about his

conduct of his financial affairs, in terms of human relationships he plainly

has quite a lot going for him.

is a bitter, indefensible distortion. I like him a great deal. More to

the point, he has effortlessly kept the friendship and esteem over 40-odd

years of men whose solidity of character and all-round integrity make

me count it a privilege to know them. So, for all the worries about his

conduct of his financial affairs, in terms of human relationships he plainly

has quite a lot going for him.