Part 1 The early years - Part

2 1966 and all that - Part 3 Indian summer

- Part 4 Football manager

Part 1 The early years - Part

2 1966 and all that - Part 3 Indian summer

- Part 4 Football manager

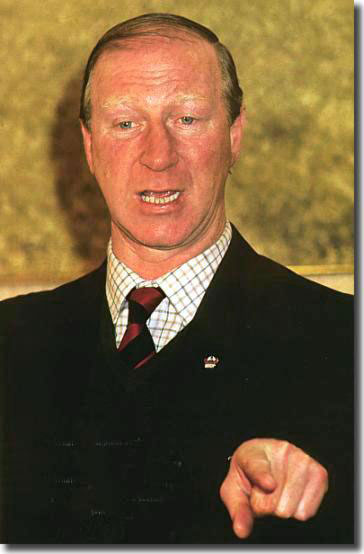

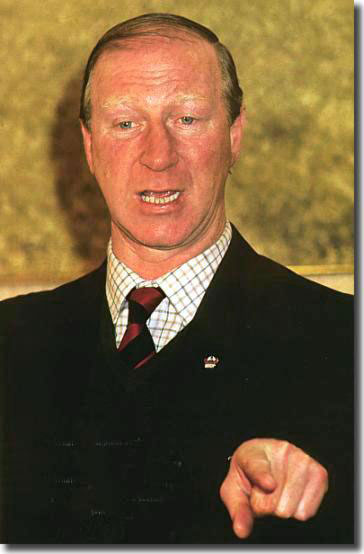

After 35 years in football and 12 in club management, Jack Charlton spent

the autumn of 1985 in his favourite pursuits of hunting, shooting and

fishing and generally enjoying life. Then in December 1985 Des Casey,

President of the Football Association of Ireland, rang out of the blue

to take him on.

Charlton: 'I like Ireland. I like the Irish people, I like a pint of

Guinness, I like the craic. I like the fishing in Ireland - in fact, I

like it so much that I've bought a house on the west coast there with

a friend, to serve as a base when we go fishing. And I wanted to be an

international team manager. If the Welsh had offered me the job, or the

Scots, or even the English, I'd have taken it, because I felt that's what

I wanted to do. So, yes, of course I was interested.'

Ireland had a lot of good players to call on at the time, although

they had never managed to do anything of note at international level.

He could pick from the Arsenal trio Frank Stapleton, David O'Leary and

Liam Brady, Mark Lawrenson and Ronnie Whelan of Liverpool, Manchester

United's Paul McGrath and Kevin Moran, without even mentioning John

Sheridan (Leeds), Ray Houghton, John Aldridge (both Oxford), Packie

Bonner, Chris Morris, Mick McCarthy (all Celtic) and many others. These

were world class players, but they just could not get their act together

as a unit.

'I informed them I didn't want a contract. I would stay for three years,

which would take us through the 1988 European Championship and into the

qualifying rounds for the 1990 World Cup. If either party was dissatisfied

at that point, the agreement would end with a handshake.

'My first game in charge of the Ireland team - a friendly against Wales

at Lansdowne Road in March 1986 - was notable for three things. Ian Rush

got the only goal for Wales, their goalkeeper Neville Southall got a broken

ankle, and I got a reputation for forgetting the names of my own players.

'It's possible that I may have called Liam Brady Ian on a couple of occasions.

I was stuck with this reputation for forgetfulness. And it became a bit

of a party piece with me. Announcing the Irish team to the press after

training, I'd go, "Bonner, Morris, Houghton, Moran - and that big

lad, what d'you call him ..." and someone would prompt me - "McCarthy!"

- without realising that I was taking the mickey yet again.

'Anyway, our next fixture was against Uruguay which we drew 1-1, and

then ... nothing.

'I needed a few games to sort out the team before we started our qualifying

programme for the European Championship just four months later - but when

I talked with the FAI, I couldn't believe how disorganised they had been.

They told me we might be going on tour to South America, there was a possibility

of a tournament in Iceland, or there might even be a game in Europe. This

was in the late spring, the last realistic chance to get the players together

before the end of the football season!

'In the event, we went to Reykjavik for a three-nation tournament involving

Iceland, Czechoslovakia and ourselves. By the time we got ready to go

to Iceland, I'd already determined which way we would play. My philosophy

of football is that it is better to do simple things well, rather than

get involved in complicated patterns which are foreign to our game. At

the time, most European teams were playing a sweeper system, with the

spare man working the ball from the back to midfield,  with

the primary aim of getting their playmaker free.

with

the primary aim of getting their playmaker free.

'We couldn't operate like that, not because we didn't have the players,

but because most of our players played in England, and the British 4-4-2

style of game was fundamentally different in its concept. Here the primary

aim was to get the ball into the box at the earliest opportunity, and

the best player in the team wasn't always the guy who played in central

midfield.

'If our midfielders had the ball, they gave it to the full-backs. They

would then drop off as far as they liked, before delivering the ball into

the corners behind the opposing full-backs, and immediately we'd push

forward to condense the area. John Aldridge would be on his way into the

corner for the ball even as it was struck and almost by definition, his

marker followed him.

'That meant that one of their three centre-backs was already drawn out

of position and a space opened up in front of goal. If Aldo got there

first, Ray Houghton would push up to support him - but I would say to

John, "Don't worry if the centre-back gets to it first, just stay

on top of him. That way he has to play the ball out of the corner and

if we've enough bodies in there, he'll find it difficult."

'When John won the ball, our other front runner Frank Stapleton would

go to the back post, a midfielder, Paul McGrath or Mark Lawrenson, would

take the near post, and now we had people in position to converge on the

cross when it came in.

'The vogue in Europe at the time was that every one of the outfield players

should use the ball constructively. That was fine as long as nobody pressurised

them, but we were about to do just that, and the effect was immediate.

Suddenly, the elegance disappeared and the assured defenders I had seen

on television now began to look a lot less composed.

back to top

'The tenets of our game plan were as simple and as basic as that. So

simple, in fact, that the opposition couldn't handle them. And when they

eventually stumbled on the answer many years later, it was more by accident

than design.' The tactics worked well in that tournament and Ireland saw

off both Iceland and Czechoslovakia, convincing Charlton that he was on

the right track.

The World Cup finals in Mexico in 1986 reinforced Jack's belief that

the only way Ireland could hope to make an impact was by imposing their

kind of pressurised football on their opponents. He covered the finals

for ITV, and used the opportunity to run the rule over three of Ireland's

European Championship opponents, Scotland, Belgium and Bulgaria.

The opener for the Irish was in Belgium's Heysel Stadium, the first big

game to be played there since the European Cup Final disaster a year before.

Ireland came away with a 2-2 draw but also a very disillusioned Liam Brady,

whom Jack had asked to play a very different game from his normal one.

The new style Ireland had adopted demanded that Brady should spend a lot

of the time pressing the Belgian full-back. He did, however, manage to

score one of the goals in a 2-2 draw.

A 0-0 home draw against Scotland followed, and in the return the Irish

pinched it with an opportunist goal from Mark Lawrenson.

A 2-1 defeat in Bulgaria was a setback, and it was mainly due to bad

refereeing decisions which contributed to both Bulgarian goals, including

a dubious penalty award. The Bulgarian centre forward Sirakov had been

instrumental in conning the ref on both occasions and he was targeted

for revenge in the return match. When another point was dropped in a scoreless

home draw with Belgium, it looked like the wheels were starting to come

off. Two close victories over Luxembourg steadied things somewhat, but

the Irish were pretty fortunate on both occasions.

'And so on to the big one, the return with Bulgaria. This was the one

we had to win, and we did - thanks to second half goals from Paul McGrath

and Kevin Moran. And Mr Sirakov? He got his come-uppance, too, but all

within the rules, you'll understand.

'That was a day when quality and passion came together in an unbeatable

formula. Brady was brilliant, just brilliant. He was playing off the front

two, taking on defenders, going to them when they had the ball, doing

everything I had entreated of him for more than a year. I remember turning

to Maurice Setters and remarking, "The penny has dropped."

'And then this gifted man, who can calculate a pass to the last roll

of the ball, goes and destroys it all. We're leading 2-0, there's only

a couple of minutes left, and as he turns away from an opponent with the

ball, he's kicked. What does he do? He spins around and kicks the guy

back, straight in front of the referee. Off! My heart sinks. Whatever

happens now, whether we get to the finals or not, he's going to pick up

a minimum two-match suspension.

'With just one team to qualify from Group 7, it was now all down to Scotland's

ability to beat Bulgaria in the last game in Sofia to get us through.

A draw would be good enough to qualify the Bulgarians on goal difference,

and to be honest, I reckoned that was the very least they would get. Not

only were they a good technical team when playing at home, but the Scots,

already out of contention, had nothing but their self-respect to play

for.'

Jack spent the day of the game shooting with a friend in Shrewsbury and

then watched the match on television. With the game still scoreless Charlton

received a phone call saying that Scotland had won and the Irish were

through. He thought it was a wind-up but the television transmission was

a delayed one and the Irish had made it into the finals of a major championship

for the first time. However, they had to play without both Mark Lawrenson

and Liam Brady who dropped out through bad injuries.

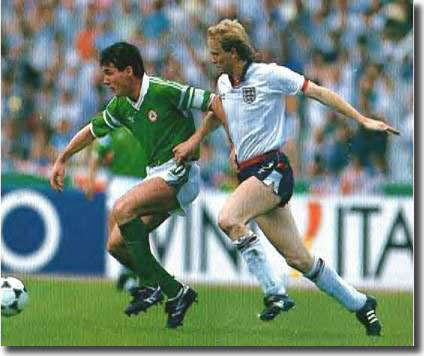

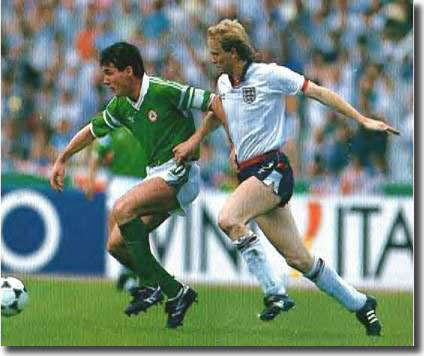

The first game of the Finals was against England, and Charlton was shocked

about exactly how much the match meant to Ireland.

'They had once beaten England at Goodison Park, but that was almost forty

years earlier. I discovered that they still talked about that win when

I first became involved with the FAI, but for a whole generation of Irish

people, victory over the English was something they had only read about

in history books.

'Against that background, the build-up to the game in Stuttgart was exceptional.

Most of the English players had been in action in the World Cup Finals in Mexico two years earlier and, as such, Germany was no big deal for

them.

in Mexico two years earlier and, as such, Germany was no big deal for

them.

'We, of course, were in a different situation. It was all new territory

for us, and my biggest job in the days before the game was to try to take

the pressure off the players and get them relaxed. Some of our training

sessions were so laid-back that they must have sent reassuring messages

to my old friend, Bobby Robson, in the England camp. And that suited me

just fine.

'The one thing that bothered me about Bobby's team was that he played

two specialist wingers, Chris Waddle and John Barnes. Given any kind of

latitude, I knew they could destroy us, so I decided to modify our game

plan just for this one occasion.

'Usually, we pressurised people, got on top of them as soon as they had

the ball. But not this time. I told the lads, "Move towards their

back four when they have it, make them feel comfortable on the ball but

not comfortable enough to look up and deliver it. Get close enough to

persuade them that, far from delivering the wide ball, their best option

is to play it across the back four." That way, their build-up from

the back would become even slower, the wingers would be forced to drop

back to take the ball, and we would then be able to handle them better.

It worked like a treat. Their two full-backs, Gary Stevens and Kenny Sansom,

could never get Waddle and Barnes into the game, and eventually the wingers

ended up having to come back to the halfway line for any scrap of possession.

'Ray Houghton had given us the lead after only a couple of minutes, and

it wasn't until relatively late in the game that they got us into any

kind of trouble. And that was down directly to the fact that Bobby introduced

Glenn Hoddle to his team on the hour.

'He had set out to beat us by playing through the middle, gradually realised

it was getting him nowhere, and then brought on Glenn to start dropping

balls over our back four from midfield. Thank God he didn't do it earlier.

We struggled to contain the new situation - and Gary Lineker in particular

- and but for a couple of marvellous saves by Packie Bonner, we might

well have lost the game. But we didn't, we won it. We'd done what we'd

set out to do, and given Ireland the win the country demanded.

back to top

'The night of the England game, we celebrated suitably. We also introduced

a new word to the players - curfew. Some of them wanted to know if it

meant a flightless, long-beaked bird, but they got the message soon enough.

We'd another big game coming up against the Soviet Union in Hanover three

days later and we needed the batteries recharged.'

Changes were needed for that game because of an injury to Paul McGrath

and players had to adapt, but 'the new formation fitted like a glove ,

and the 1-1 scoreline at the finish did not do justice to the way we played.

It was probably as good a performance as any Ireland had produced away

from home. The memorable points for me were Ronnie Whelan's strike, the

goal we gave away, and the reaction of the Soviet manager after the game.

In every respect other than the scoreline, we had won hands down - and

the Soviet manager knew it. A couple of days earlier, he had done what

he probably considered the hard bit by beating the Dutch. Now, he knew

more than most that his team had been second best against us. He shook

hands without even looking at me, but I'd never seen a more disappointed,

down-in-the-mouth expression on the face of any manager in my life.

'The result meant that we now needed only a point from our last game

against Holland at Gelsenkirchen to reach the semi-finals. With  Paul

McGrath fit for action again, I was pretty confident we'd get it. That

was until we got to the stadium on match day and discovered that the temperature

was in the high nineties for the afternoon kick-off.

Paul

McGrath fit for action again, I was pretty confident we'd get it. That

was until we got to the stadium on match day and discovered that the temperature

was in the high nineties for the afternoon kick-off.

'Ours was a pressure style, involving an inordinate amount of running.

After two hard games in the preceding six days, I feared that legs would

go in that kind of heat. To combat it, we devised a plan under which the

ball would be played back to Bonner at every opportunity. He would then

hold it and bounce it for ten to fifteen seconds, giving our players a

brief respite. What Packie was doing was perfectly legal. There was no

rule in the book which prohibited a keeper from bouncing the ball. But

I noticed the referee was getting increasingly annoyed with him in the

second half and I feared that he was about to lose his patience. The plan,

regrettably, had to be ditched - and with it went our chance of getting

to the last four. Now there were no rest periods, everybody had to chase

and run, and suddenly the Dutch were in control of a game in which we

had gone closest to scoring with McGrath's header against a post. But

with only seven minutes to go, we were still holding them, when disaster

struck.

'Ronald Koeman's mishit shot looked to be going well wide until Wim Kieft,

only in the game as a replacement, got his head to it, and the ball, getting

something akin to a leg break in cricket, sneaked in at the far post.

'Of all the ways to lose a game! We had competed like Spartans for three

games, played well enough to have won all three, and yet we were out of

the championship - all because of the biggest fluke of the year.'

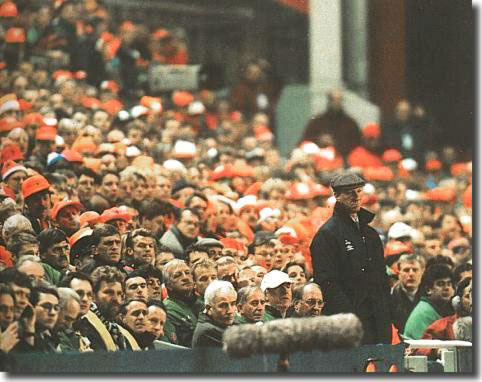

The qualifying competition for the 1990 World Cup pitted Ireland against

Northern Ireland, which was potentially a highly sensitive political situation.

The first game was at Windsor Park in Belfast and Jack had to put up with

some insults from the crowd.

'I just smiled at the hostile supporters and when I put my head through

the wire barrier and asked one of them for a light, I think it helped

defuse the situation marginally. In fact, there wasn't much in the game

to match their passion. It was tough and tense, just like an English club

derby. We probably had the edge in scoring chances, but it still took

a couple of good saves by Gerry Peyton, deputising in goal for Packie

Bonner, to earn us a point from a scoreless draw.

'Apart from Northern Ireland, Spain and Hungary were the danger teams

in the group, and when the meeting to arrange dates and venues for the

games was held earlier in the year, I took a calculated risk. I decided

to open our programme by playing the three hardest games away from home,

in the hope that the competition wouldn't yet have developed a fine edge

at that point.'

The gamble looked like it had backfired when a below-strength Irish side

lost 2-0 to Spain in Seville - they were taken apart.

'Fortunately, we had a full-strength squad when we went to Budapest for

our next game, but in spite of dominating the Hungarians, we still had

to content ourselves with just one point from a scoreless draw. A couple

of years earlier, a draw in Hungary would have been interpreted as a smashing

result. Now the Irish press were complaining that we didn't take our chances

and that we should have won the game! I agreed with that assessment, but

the criticism served to remind me that expectation in Ireland was now

reaching a disturbing level.

'Still, that was the price of the job I'd taken on board - and when we

met Spain in Dublin in April 1989, I knew that our margin of error was

zero. This was the game we had to win to stay competitive in the group,

and the fact that the Spaniards had made our improvised team look so inadequate

in Seville had the effect of focussing minds. They'd had their hour of

glory. Now it was time for us to show them that, with a full-strength

side, they were only second best.

'We did what we needed to do, and a 1-0 win put us back on track to qualify

for the 1990 World Cup Finals. Officially it was credited as an own goal,

but Stapleton was waiting to knock Ray Houghton's cross into the net when

Michel's outstretched foot saved him the trouble.

'The Spanish result also vindicated me, I believe, in my decision to

take the difficult part of our programme at the beginning. By now we were

pretty well unbeatable at home - and with Hungary, Northern Ireland and

Malta still to play at Lansdowne Road, we were in good shape approaching

the end of the season.

'Before we broke for our summer holidays, however, we had to take care

of the Maltese and the Hungarians, and this was achieved without too  much

bother. Both games were won with 2-0 scorelines, and against the Hungarians

in particular, we played some good football.'

much

bother. Both games were won with 2-0 scorelines, and against the Hungarians

in particular, we played some good football.'

back to top

Before the rest of the games, Ireland had a friendly at home against

West Germany and Charlton used the game to look at three players who were

nearing the end of their careers, Liam Brady, Frank Stapleton and Tony

Galvin. A Stapleton goal put the Irish in front after 10 minutes, but

the Germans equalised before half-time and Brady was struggling. Charlton

pulled him off just before half-time and Brady reacted very badly. He

announced his international retirement after the game, which ended in

a 1-1 draw.

In their return match with Northern Ireland the team laboured, but eventually

ran out 3-0 winners. A 1-0 win in Malta followed and Ireland had qualified

for another set of major finals.

'Ireland's participation in Italia 90 would prove a lot of things to

a lot of people. Our performances in the European finals two years earlier

had made many of our peers sit up and take notice. Now we would show that

it was no flash in the pan - that we deserved to rank among the better

teams in the game.

'In Sardinia, just as we had done in Germany, we were to open our programme

against England - and then we would move to Sicily for the remaining first

phase games with Egypt and Holland.

'In my team talk, I went over the way England would play, the pattern

they would adopt and how we would cope with it. John Barnes and Chris

Waddle were still there, but the point which reassured me most was Bobby

Robson's choice of Bryan Robson and Paul Gascoigne in central midfield.

Bryan was one of the best midfielders England ever had, but they never

seemed to be able to find the right player to complement him. And that

was because he was so good at so many things. It would have been fine

if Bobby had left him to anchor midfield, but Bryan was also expected

to get forward and get the odd goal or two. And because of that dual responsibility,

it was never easy for them to find the right partner for him.

'Gascoigne certainly didn't meet that requirement. A strong runner and

a superb passer of the ball, he's at his best on the edge of the opposition's

box. At the other end of the pitch, he is a liability. He tries to be

too clever, aiming to nutmeg people or to pull the ball down, when a specialist

defender would just hoof it. I reckoned the more pressure we put on him,

the better.

'Neither Barnes nor Waddle was good defensively - Chris couldn't tackle

his own mother in a cupboard - and in that situation, I reckoned Bobby

didn't have enough ball-winners to prevent us getting at his back four.

As it turned out, I was right.

'We gave away a silly goal to Gary Lineker, but got no more than we deserved

when Kevin Sheedy equalised in the second half. After that, we were always

the more likely team, though we never managed another goal.

'The scoreless draw which followed against Egypt was notable from my

point of view for the fact that I got myself into trouble with the press

in both Cairo and Dublin. I lashed the Egyptians' attitude to the game

for the simple reason that I couldn't understand how players which had

battled their way through to the qualifying rounds could be so negative

when they arrived in the finals.'

A 1-1 draw with Holland in the final group game was enough to put both

sides through with England, who beat Egypt 1-0. The Irish and the Dutch

virtually settled on a draw when they heard England were winning.

'Conditions in Genoa for our quarter-final with Romania were absolutely

gruelling. The stadium was totally enclosed, there wasn't a breath of

air in the place, and with a capacity crowd ringing the pitch, the heat

was unbelievable. Both teams suffered, but I saw enough of the Romanians'

class in the opening twenty minutes to convince me they were a very dangerous

team.

'Gheorghe Hagi had a tremendous left foot, and twice almost scored before

we had settled. It was in moments like those that I was glad I had a player

like Packie Bonner in goal. We gradually got back into the game in the

second half, without ever breaking down a strong defence. It was all very

taut and tense.

'In extra-time, neither side threatened to score, for the simple reason

that they didn't have the energy to push on and look for a goal. Inevitably,

it went to a penalty shoot out, the first in the history of the competition.

The idea was so novel that I hadn't even taken the precaution of  nominating

our penalty-takers in such an eventuality. That was laxness on my part

- but in reality, we knew who our best penalty-takers were.

nominating

our penalty-takers in such an eventuality. That was laxness on my part

- but in reality, we knew who our best penalty-takers were.

'John Aldridge, our penalty specialist, was out of the game at that stage.

I walked across to the players who were sat in the centre circle and asked,

"Who's going to take them?" Various hands went up, and the only

one that surprised me was David O'Leary, who had replaced Steve Staunton

in extra time. He said he'd have one, providing he was allowed to go last.

Fine.

'I was quite relaxed at that stage. We'd done well to reach this far.

Whatever happened now, nobody could say that we hadn't made our presence

felt. My only instruction was, "Make up your mind what you're going

to do and don't change it!"

'I was a bit annoyed with the referee. The instruction was that as the

players went to the penalty spot, they turned and showed him their number.

But on three or four occasions after our lads had placed the ball, he

beckoned them to him and made them turn around. He never did that with

the Romanians.

'Their keeper nearly got to Tony Cascarino's shot, but all kicks had

been successful when Daniel Timofte put the ball down for Romania's last

attempt. I've watched it on video a dozen times since, and it wasn't a

good penalty. It was struck at a comfortable height, and the only chance

he had of scoring was if Packie went the wrong way. But he didn't, and

after going close to stopping the previous one, Packie read the line perfectly.

'And so to O'Leary. I didn't know at that point that he had never previously

taken a penalty and it was just as well I didn't!

'I was now really uptight. I hadn't smoked for a couple of years, but

now I desperately needed a fag. So I turned and cadged one from an Italian

spectator, and then stuck my head through the wire for him to light it.

In the next day's papers there was a picture of me looking the other way

as David ran up to the ball, with the caption "Jack couldn't bear

to watch." Nonsense! Of course Jack could bear to watch - except

that with so many players stood in front of me, I thought it better to

look at the big video screen at the other end of the stadium.

back to top

'And then my nerve almost went. I put my hands over my face and said,

"No, I'm not watching this." But I pulled them away just in

time to see David send the goalkeeper the wrong way. Easy as winking!

And all of a sudden, the lads are running, all determined to pile themselves

on top of O'Leary and Bonner.

'We're through! For the first time, Ireland are within touching distance

of the World Cup. We're in the last eight, the last bloody eight! More

than that, we're headed for the biggest stage of all, a quarter-final

tie against Italy in the Olympic Stadium in Rome.

'Shortly after arriving in Rome, I discovered that our game was to be

refereed by a Portuguese official - and that worried me no end. I have

always been wary of match officials from that region.  I'm

not saying they are out to stop you winning a game, but their interpretation

of the laws, as I discovered on trips abroad with Leeds, England and Ireland,

is vastly different to the rest of the world.

I'm

not saying they are out to stop you winning a game, but their interpretation

of the laws, as I discovered on trips abroad with Leeds, England and Ireland,

is vastly different to the rest of the world.

'If you raise a boot five inches, they whistle. If you jump with an opponent,

they whistle. If there is any kind of physical contact whatever, they

whistle. And since our game plan was based in part on hustling and pressurising

opponents, it didn't augur well for our prospects in the Olympic Stadium.

'And this was no ordinary Portuguese official. He was none other than

Silva Valente, the man who had caused me to stand principle on its head

and to have a go at him, publicly, in that European Championship game

in Bulgaria a couple of years earlier.

'Two diabolical decisions that day had cost us the game - and while he

didn't do anything quite as drastic in Rome, he was certainly no help.

Every time we got a bit of momentum going, he would stop the game for

one reason or another. But they were always thirty or forty yards out.

We had difficulty getting anywhere near their goal.

'Toto Schillaci's goal hurt in more ways than one. It was a bloody stupid

score to concede, coming directly as a result of Kevin Sheedy playing

a silly ball to John Aldridge. In our match plan, we gave the ball into

the corner for the runner, but this time, strangely, John showed for it

and Kevin played it to his feet.

'That was inviting trouble, and sure enough, we got it. The Italians

swept the ball three-quarters the length of the pitch in the twinkling

of an eye, and when Packie could only parry Roberto Donadoni's shot, Schillaci

stuck the rebound in the net.

'We were out of the World Cup, the dream was over - and all because of

one lapse of concentration. We had done better than anybody could reasonably

have expected ... and yet the thought persisted that it could have been

even better.' In the qualifying rounds for the 1992 European Championships,

Ireland kicked off with a home game against Turkey, which they duly won

5-0, but this was deceptive.

'Our next two games were against England, home and away, and we twice

let them off the hook, allowing them to escape with 1-1 draws when we

should have won both matches easily. Ray Houghton missed a sitter in the

Dublin game - and, incredibly, did the same thing again when we went to

London, for a fixture which brought out Wembley's biggest crowd in years.

'We had started badly, with Steve Staunton deflecting Lee Dixon's shot

past Packie Bonner, but then proceeded to give them a lesson in our pressure

game. For the best part of ten minutes, we pinned them in the top third

of the pitch. I heard Graham Taylor roar at his players, 'Get out, get

out.' But we had them ringed so tight that they couldn't get out. In ten

years, that was the single best illustration of our ability to pressurise

opponents.

'Eventually, Niall Quinn knocked in the equaliser from Paul McGrath's

cross, but that was the very least we deserved to take out of the game.

I mean, if we'd won 3-1 nobody, not even the most dyed-in-the-wool England

supporter, could have complained about the scoreline.

'But Kevin Sheedy on his wrong foot missed from no more than a couple

of yards, before Houghton compounded it all in the last few minutes by

shooting just past David Seaman's left-hand post when it looked so much

easier to bury it in the net. That was typical of Ray, a brilliant player

around the pitch, but not the most reliable when it came to finishing.

And I remember saying to them at the end of the game, "That's the

chance which could cost us a place in the European finals." Never

did I speak truer words.

'By the time we got to our last two games in Poland and Turkey, it was

tight, desperately tight, as to  whether

England or ourselves would get the one qualifying place on offer in the

group. For the Polish game in Posnan, I decided to change tack. Instead

of going with two front players, I played a fifth midfielder. The plan

was for Roy Keane and Andy Townsend to run at the Poles from deep positions

and get on the end of crosses from our full backs.

whether

England or ourselves would get the one qualifying place on offer in the

group. For the Polish game in Posnan, I decided to change tack. Instead

of going with two front players, I played a fifth midfielder. The plan

was for Roy Keane and Andy Townsend to run at the Poles from deep positions

and get on the end of crosses from our full backs.

'For more than an hour it worked brilliantly. Time after time, we punched

holes in their defence, and with twenty minutes to go, we led 3-1. But

then came the miscalculation. Frankly, I hadn't reckoned on how much our

running game would take out of our players, and with our midfielders forced

backwards to the point where they finished up on top of our defenders,

the Poles got in for two late goals to save a point.

'To qualify, we needed to beat Turkey in Istanbul and then depend on

the Poles doing us a favour at the same time against Graham Taylor's team.

And boy, did we give it a whirl! I had always found Turkey a difficult

country to play in every time I went there. The spectators are very hostile.

To win a game, you always had the impression that you had to beat the

crowd as well as the Turkish team.

back to top

'It quickly became apparent that this would be a test of character as

much as skill, and the lads responded magnificently. John Byrne, back

in the side after a long absence, gave us an early lead, and while they

equalised from a doubtful penalty, we quickly got back on top again to

win with further goals from Byrne and Tony Cascarino. Great! And the word

from Poland was even better. England are losing 1-0. If it stays like

that, we're on our way to Sweden for the finals the following summer.

'As I'm walking off the pitch at the end, the Turkish manager, Sepp Piontek,

an old friend of mine, comes across to congratulate me. He says that Poland

have won in Posnan.

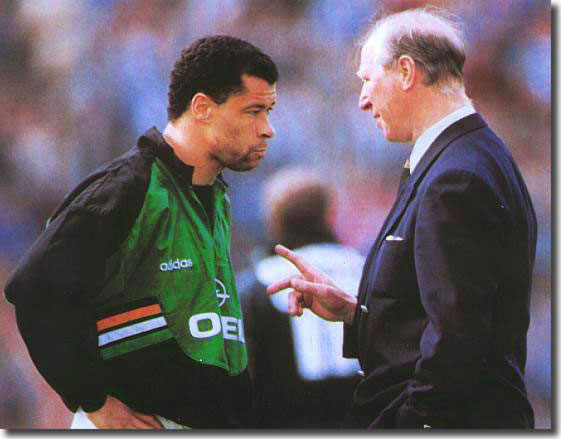

'I can't wait to get inside to congratulate the lads, when suddenly,

out of the corner of my eye, I catch a glimpse of Mick McCarthy. His face

is about three feet long. "What's wrong, Mick?" I ask. "You

haven't heard, then," he says sadly. "Gary Lineker has just

gone and scored for England - we're out."

'In the space of not more than ninety seconds, I had gone from the summit

all the way down to the valley, and the experience was awful. We haven't

lost a game in the competition, we've squandered a hatful of chances along

the way and now, we miss out on the finals by six or seven minutes!'

Soon after that disappointment, 1994 World Cup qualifying began and Ireland

faced Denmark , Spain, Northern Ireland, Latvia and Lithuania. Ireland

beat Latvia in their first game and then faced the Danes. The game in

Copenhagen ended in a scoreless draw, which was also the score when Ireland

visited Spain in Seville the following month.

'Nobody had ever gone there and beaten Spain in a big game, but I tell

you something, we came pretty close to it that night. Late in the game,

John Aldridge chested the ball past their centre back, took it around

the keeper and put it into the empty net. To everybody in the stadium,

it was a perfectly good goal. I couldn't believe what I was seeing when

a linesman stuck up his flag for offside.

'It was a disappointing result on the night, but with two vital away

points to go with the win in Latvia, I was reasonably content on the journey

home.

'A 3-0 win over Northern Ireland in Dublin could have been doubled had

we not stopped playing in the second half, and while a 1-1 draw in the

return meeting with Denmark at Lansdowne Road was disappointing, I still

thought we were in good shape facing up to our summer programme in eastern

Europe.

'After a nightmare stay and a friendly win in Albania, we banked six

important points by winning 2-0 in Riga and beating Lithuania 1-0 in Vilnius

the following week.

'By the time we got to our second last game, against Spain in Dublin,

we knew exactly what we had to do to qualify. A win over the Spaniards

would be enough to put us out of the reach of the rest and spare us the

need to get a good result against Northern Ireland in Belfast the following

month.

'Spain had never been the best of travellers in international football,

but they caught fire in the rain that day and simply destroyed us. They

were a goal up after just twelve minutes, scored a second time when Alan

Kernaghan got himself into trouble by refusing to do the simple thing

in a tussle with Julio Salinas - and when Salinas scored again before

half-time, there was just no way back.'

John Sheridan pulled a goal back in the second half to steady things,

but Ireland now needed to beat Northern Ireland to make certain of going

to America for the finals. A draw could still result in qualification

on goal difference, but only if Spain beat Denmark in the other game.

back to top

A 1-1 draw gained by a goal from sub Alan McLoughlin after a 25-yard

volley from Jimmy Quinn took the lead was enough when Spain beat Denmark

1-0 in the other game.

In the weeks before the 1994 World Cup finals in America, Ireland went

on to win 1-0 in Holland and then 2-0 in Germany in their last game before

the finals. The World Cup finals themselves were marked by blistering

heat and conditions which did not favour the Irish. Strict conditions

around refreshments also led to some problems. On the day of their first

game against Italy in New Jersey, it was well into the nineties.

'By any standard, it was a remarkable game. For one thing, the setting

was like nothing else I'd ever experienced. It's not often the Italians

are outnumbered in New York, but take it from me, this was one of them.

I mean, there must have been 40,000 Irish people form all over the world

in the stadium, and hell, did they make their presence felt! It was carnival

time all the way, and, of course, we got the result we wanted.

'The game had only been on for ten or twelve minutes when Ray Houghton

pulled down a bad clearance by Francesco Baresi, and from the edge of

the box chipped the goalkeeper, sweet as a nut. Six years earlier, I had

seen

Ray produce another crucial goal against England at roughly the same stage

of the game, and I remembered how we had sat and suffered for the remainder

of the match, minute by agonising minute. But not this time.

seen

Ray produce another crucial goal against England at roughly the same stage

of the game, and I remembered how we had sat and suffered for the remainder

of the match, minute by agonising minute. But not this time.

'From there on, we gave every bit as good as we got, and should have

had a second goal when John Sheridan, taking a superb pass from Roy Keane,

thumped the ball against the crossbar. Bloody great stuff. Out there playing

us was one of the most respected teams in the world - and yet we handled

them comfortably. Paul McGrath was magnificent; Roy Keane and Andy Townsend

got among the Italians in midfield; and up front, Tommy Coyne was bravery

itself.'

back to top

The next game was against Mexico and the conditions were just as oppressive.

Ireland started well enough, but gradually wilted as the Mexicans got

on top and established a 2-0 lead. There was also enormous controversy

when the officials prevented John Aldridge coming on as substitute for

what seemed an age, leaving Ireland with only ten men. When he did get

on he pulled a goal back, which meant that a draw in the next game against

Norway would be good enough to see them through.

Ireland managed that draw quite effectively, which set up a game in the

last sixteen with Holland in Orlando.

'In spite of the fact that we had beaten Holland in Tilburg just a couple

of months earlier. I was wary of the Dutch. They had a lot of good players

who could turn it on, and we needed to be very careful about letting them

get at our back four.

'Still, they caused us no problems at all, until a silly mistake by Terry

Phelan turned the whole competition sour for us. Terry had ample time

to knock the ball away, but instead he let it bounce and then, from a

distance of twenty five yards or more, attempted to head back in the direction

of Packie Bonner. There was never enough pace on the ball to enable him

to do that, and Marc Overmars, reading the situation perfectly was away

and running. Phil Babb and Paul McGrath had been caught square by Phelan's

gaffe, and when Overmars crossed, Dennis Bergkamap had a simple job in

sliding in the first goal.

'Crass carelessness had cost us a vital score, but if that was bad, even

worse was to follow. There were at least five Irish players between Wim

Jonk and the goal when he let one go from all of thirty yards. Whether

Packie misread the line of the shot, or whether the ball swerved in the

air, I'll never know. But instead of making the straightforward save,

he allowed the ball to clip the top of his fingers, and it dropped ever

so gently over the line for a second and clinching goal.'

So Ireland were out and there was a massive sense of anti-climax. They

had achieved probably as much as they were expected to do, but it still

felt very disappointing.

It was about then that Jack decided to quit.

'When Holland put us out of the European Championships in a play off

at Anfield in November 1995, I knew that it was the time for me to say

goodbye. The question was when, and because of the uncertainty - partly,

I have to say, of my own making - I ended up in a situation in which for

the first time in almost ten years, I had aggro with the Football Association

of Ireland.

'It should never have come to that. For one thing, we should have qualified

for the European finals. Halfway through our qualifying programme, I was

absolutely certain that we would. But then we lost a couple of key players

at vital times, and for a small outfit like ours that was ruinous. Ever

since I took the job, I'd staked my reputation on building a squad in

which I had at least one viable option in all eleven positions in the

team. I prided myself on the fact that despite limited resources, we had

achieved that.

'But then we lost players like Roy Keane, Andy Townsend, John Sheridan

and Steve Staunton. From a position in which we were coasting through

our programme, I watched the old confidence disappear before my eyes.

After losing three of our last four matches, I sensed that the show was

almost over as we got ready to go to Liverpool for the meeting with the

Dutch.'

And that was that. Ireland lost out to a Patrick Kluivert goal and Jack

resigned on 21 January 1996, just short of ten wonderful years from the

date he took on the task of making Ireland, for a while at least, one

of the best international sides in the world.

Part 1 The early years - Part

2 1966 and all that - Part 3 Indian summer

- Part 4 Football manager

back to top

Part 1 The early years - Part

2 1966 and all that - Part 3 Indian summer

- Part 4 Football manager

Part 1 The early years - Part

2 1966 and all that - Part 3 Indian summer

- Part 4 Football manager with

the primary aim of getting their playmaker free.

with

the primary aim of getting their playmaker free. in Mexico two years earlier and, as such, Germany was no big deal for

them.

in Mexico two years earlier and, as such, Germany was no big deal for

them. Paul

McGrath fit for action again, I was pretty confident we'd get it. That

was until we got to the stadium on match day and discovered that the temperature

was in the high nineties for the afternoon kick-off.

Paul

McGrath fit for action again, I was pretty confident we'd get it. That

was until we got to the stadium on match day and discovered that the temperature

was in the high nineties for the afternoon kick-off. much

bother. Both games were won with 2-0 scorelines, and against the Hungarians

in particular, we played some good football.'

much

bother. Both games were won with 2-0 scorelines, and against the Hungarians

in particular, we played some good football.' nominating

our penalty-takers in such an eventuality. That was laxness on my part

- but in reality, we knew who our best penalty-takers were.

nominating

our penalty-takers in such an eventuality. That was laxness on my part

- but in reality, we knew who our best penalty-takers were. I'm

not saying they are out to stop you winning a game, but their interpretation

of the laws, as I discovered on trips abroad with Leeds, England and Ireland,

is vastly different to the rest of the world.

I'm

not saying they are out to stop you winning a game, but their interpretation

of the laws, as I discovered on trips abroad with Leeds, England and Ireland,

is vastly different to the rest of the world. whether

England or ourselves would get the one qualifying place on offer in the

group. For the Polish game in Posnan, I decided to change tack. Instead

of going with two front players, I played a fifth midfielder. The plan

was for Roy Keane and Andy Townsend to run at the Poles from deep positions

and get on the end of crosses from our full backs.

whether

England or ourselves would get the one qualifying place on offer in the

group. For the Polish game in Posnan, I decided to change tack. Instead

of going with two front players, I played a fifth midfielder. The plan

was for Roy Keane and Andy Townsend to run at the Poles from deep positions

and get on the end of crosses from our full backs. seen

Ray produce another crucial goal against England at roughly the same stage

of the game, and I remembered how we had sat and suffered for the remainder

of the match, minute by agonising minute. But not this time.

seen

Ray produce another crucial goal against England at roughly the same stage

of the game, and I remembered how we had sat and suffered for the remainder

of the match, minute by agonising minute. But not this time.