|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

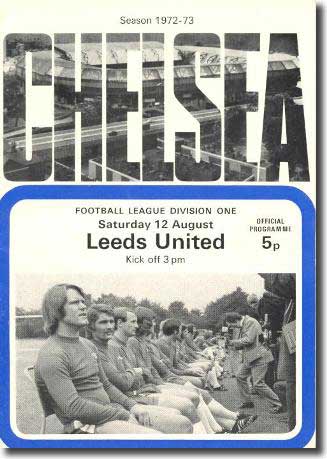

First Division - Stamford Bridge - 51,102

Scorers: None

Chelsea: Bonetti, Harris, McCreadie, Hollins, Dempsey, Webb, Garland, Kember, Osgood, Hudson, Cooke

Leeds United: Harvey, Reaney, Cherry, Bremner, Ellam, Madeley, Lorimer, Bates, Jones (Yorath), Giles, E Gray

Although 24-year-old David Harvey had proved a few months

earlier that he was one of the most outstanding young keepers in the game

as he helped United win the FA Cup for the first time, Leeds fans were

still coming to terms with Harvey's promotion over long time first choice,

Gary Sprake. That same afternoon Sprake was playing for United reserves

against West Bromwich Albion at Elland Road; joining him was former England

centre-half, Jack Charlton, now

37, and nearing the end of a 20-year career with Leeds. Terry Cooper, one of the world's best left-backs, also missed

the Chelsea trip, nursing the fractured leg he sustained against Stoke

City four months earlier. Completing the list of absentees were Norman Hunter and

Allan Clarke, both unavailable through suspension. During the close season, Whites

manager Don Revie had recruited defensive reinforcements, signing

the two Huddersfield Town centre-backs, Trevor Cherry and Roy Ellam, and

both men made their United debuts at Stamford Bridge. Though Cherry wore

Cooper's No 3 shirt, he partnered Ellam at the heart of the back four,

with Paul Madeley playing left-back. Of the customary rearguard, right-back

Paul Reaney was the only member on show. Mick Bates lined up alongside Billy Bremner and Johnny Giles

in a midfield three with Peter Lorimer and Eddie Gray supporting spearhead

Mick Jones. Terry Yorath was named substitute. If United's team had an unfamiliar ring to it, the West

London surroundings were every bit as alien. Brian Woolnough in the Yorkshire

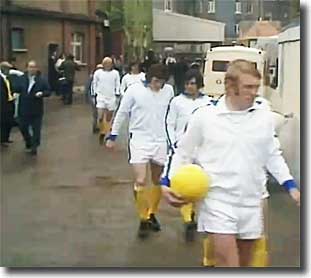

Evening Post: 'The massive redevelopment project at Stamford Bridge

means that Leeds United players will change in portable changing rooms

and receive treatment in a caravan when they open their League programme

against Chelsea on Saturday. The whole of the East Stand has been knocked

down, leaving the popular side of Chelsea's ground a mass of rubble and

bricks. 'Chelsea have spent £30,000 on portable accommodation for

the players, who will also have to walk 75 'Directors, the Press and season ticket holders have been

switched to the North Stand, the stand closed last season because of shuddering

reports… "We have told the season ticket holders who will use that

stand that they will be refused admission if they are not in their seats

15 minutes before the start," said Chelsea secretary Tony Green today.

"We just couldn't have them walking along the pitch when the game

was about to start or even in progress." 'Stamford Bridge still looks a complete shambles and Green

admitted: "There is a lot of work to be done before Saturday. Another

headache is getting the public used to the new site and entrances." 'Chelsea are expecting a 50,000 crowd for the visit of United.

It will be a severe test of their temporary arrangements but a good guide

for the rest of the season. 'This is the first stage of Chelsea's £5,500,000 new look

plan. The new East Stand - a two-tier cantilever stand costing £1m - will

not be in operation until the beginning of next season. So all clubs face

changing in portable accommodation this season.' There were more than 50,000 people packed into the Bridge

for the game, and many of the younger supporters spilled out onto the

old greyhound track after a barrier buckled in the Shed End. This doubtlessly

averted potential problems on the terracing later in the day. Chelsea

were pilloried by the Press for the chaos before and during the game.

The club subsequently cut the standing capacity of Stamford Bridge by

7,000 and during the reconstruction period the crowd limit was set at

44,000. The club's plans for the transformation of Stamford Bridge

were almost fatally ambitious, comprising the development of a 60,000

all seater circular stadium. The project was described as the 'most ambitious

ever undertaken in Britain' and the timing could hardly have been worse.

The project coincided with a global economic crisis and was hit by delays,

a builders' strike and shortage of materials, all of which sent the costs

spiralling viciously, to the extent that the club were £3.4m in debt by

1976. Between August 1974 and June 1978, Chelsea were unable to fund any

transfers and had to sell their own star players to support the huge financial

drain. In August 1972, though, Don Revie was understandably cautious

about the threat posed by Chelsea, considered by many as potential champions.

The United boss warned, 'They have a first class squad of players and

the experience to do well. We know we start with a difficult match.' The Blues had added two forwards, Chris Garland and Steve

Kember, since they beat United in the 1970 FA Cup

final, but the rest of their starting eleven had been regulars for

the preceding two or three seasons and were very much a force to be reckoned

with in their own stadium. After a fine sunny morning in West London, the match began

in steadily falling rain. United kicked off wearing Chelsea were the first to show any attacking intent, with

Kember feeding Charlie Cooke out on their left, but Reaney alertly intervened

to halt the move in its tracks and United were soon pressing forward.

They had a free kick in the Chelsea half after four minutes which Lorimer

swung high towards Peter Bonetti's goal, but the keeper came out to gather

confidently. Chelsea continued to enjoy the best of the play, with Alan

Hudson exerting some early influence. The midfielder fired over one cross

from the right, only for Cooke to chip wide, and then worked his way cleverly

to the edge of the United area before hammering in a shot which Harvey

had to punch away. The Leeds keeper had to save smartly thereafter from two

corners and was clearly winded following the second of these incidents.

However, he resumed following treatment from Les Cocker and seemed able

to cope with whatever handicap he was suffering, plucking a high cross

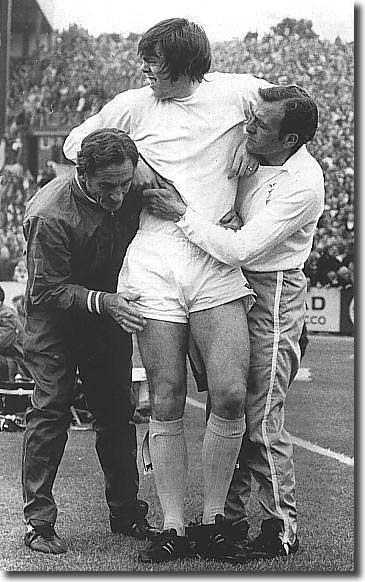

out of the air as Peter Osgood went up with Reaney to challenge. In the 25th minute the game turned fatefully against United.

Mick Jones injured an ankle in a tackle and, as reported by Albert Barham

in The Guardian, 'Yorath, the substitute, flexed his muscles but

was waved back by Bremner, for, at the moment Yorath was about to come

on to the pitch for Jones, Harvey, the goalkeeper, was being carried off

for attention behind the goal. He had earlier in the game been heavily

buffeted at a couple of corners when he appeared to collide with Ellam.

Eventually he was wheeled away on a stretcher to spend the night in Fulham

Hospital with concussion. 'In fact, the attempt to get Jones to walk proved that he

could not continue either, so it made no odds which of them Yorath was

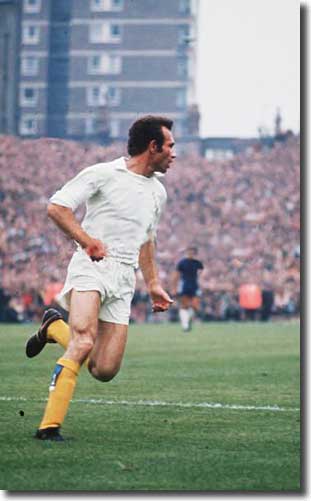

substitute for. Lorimer wore Harvey's jersey and at one stroke Leeds had

lost a goalkeeper and two aggressive forwards. Small wonder they are the

most superstitious team in the country; ill luck seems to hover over them.' In such adverse circumstances, Yorath was forced to take

up the cudgels in the unaccustomed role of lone striker, a position for

which he was ill suited. There was no chance of Lorimer being shielded from the thrust

and slash of the Chelsea forward line and he was soon under the severest

of examinations. He showed a remarkable aptitude for life between the

posts, diving to save at Cooke's feet, Chelsea continued to pile the pressure on, provoking some

moments of tetchy ill temper. Kember clashed fiercely with Bremner, prompting

stern words for both men from Swansea referee Tommy Reynolds, though only

the Chelsea man had his name taken; then Giles received a lecture for

a stiff challenge on Hollins. That was enough for the referee who called

the two captains together in order to lay down the law, stressing the

importance of cool heads. Just when it seemed that United would make it to the interval

without conceding, Chelsea opened the scoring. As the match ticked into

time added on, Garland was given the freedom of United's penalty area

and took the opportunity to make his way across the face of goal before

attempting the shot. His effort was bravely blocked at point blank range

by Lorimer but Peter Osgood was on hand to slip home the rebound. It had been a long time coming and United had done exceptionally

well to hold out for twenty minutes with ten men and a substitute keeper;

it was inevitable, though, that the home side would make their advantage

count and they were straight back at Leeds when the game restarted. Hollins made space for himself but fired high over the bar

in his over eagerness to shoot, and then Lorimer came out with some assurance

to gather a high cross from Kember. The Scot continued to surprise the

onlookers with a sound display of goalkeeping, turning an Osgood shot

round the post and then saving a low shot from Hollins. However, he could

not sustain such heroics indefinitely. As the harassed United defence struggled to keep their heads

above water, debut man Cherry was booked for scything down McCreadie after

50 minutes as the Chelsea captain was going full tilt down the flank. A minute before the hour, the Blues registered the long

expected second goal. Hudson got hold of the ball in his own half and

then freed Cooke down the left with an astute long ball. The Scottish

wing man headed goalwards and hammered an angled shot low past the helpless

Lorimer. The game was now being played out almost exclusively in

the United half, but the men in white made a rare excursion upfield which

ended with Giles getting in a shot. It would have been understandable

had Bonetti, for so long an isolated spectator at the feast, been undone

by a lack of concentration, but he was alert to the danger and saved the

effort. That kind of respite for the Leeds defence was now all too

rare and Garland added Chelsea's third goal after 68 minutes. Cooke fired

a low pass across the face of goal, Osgood feinted to accept it, deceiving

and wrongfooting Ellam, and Garland accepted the opportunity coolly, sliding

home his shot. Three minutes later, Yorath became the second United player

to have his name taken, going into the book for a foul on the effervescent

Cooke. It was more frustration than any genuine malice that prompted the

Welshman's Five minutes from the end, Garland got his second goal and

Chelsea's fourth. The former Bristol City striker headed home after some

long crossfield passing between Cooke on the left and Ron Harris on the

right gave the Chelsea full-back the opportunity to swing over a telling

cross. It was like the last fatal strike of a matador ending the

misery of a bull; minutes later United trooped off the pitch a well-beaten

and dishevelled outfit. As Barry Foster observed in his report for the Yorkshire

Post, it might have been a very different outcome but for United's

early misadventures. 'The match was finely balanced until midway through

the first half. Then Leeds received a double blow that, despite a brave

effort, they could not weather. One minute they were holding their own,

although already hit by injuries and suspensions to top players, the next

they had lost their centre-forward and goalkeeper - and not even a side

with the depth of talent of Leeds United can take that kind of medicine. 'The two new boys from Huddersfield, Ellam and Cherry, had

made a cautious start and were just beginning to settle down when first

Jones went off with a twisted ankle and then, in the same minute, Harvey

followed him, leaving Leeds, with their substitute on, down to ten men.

Harvey had received attention after a heavy goalmouth collision in the

11th minute but another heavy fall had left him dizzy and a stretcher

was called in. 'For the two injured it meant an unhappy start to the season,

for Ellam and Cherry it meant a nightmare debut situation and for Leeds

as a team it left a task to test the most gallant hearts. They rose to

it well, with Madeley and Reaney giving 'Until the setback Leeds had shown the class, Chelsea a

lot of skill. After it, one sat back and waited for the goal cloud to

burst and reflected that matches between these two sides almost always

produce the unusual incident with Leeds not often the beneficiaries. 'Lorimer set about his task well. Ironically he had been

practicing hard during the week for just such an emergency and he showed

the value of that effort but Chelsea, particularly in the second half,

tested him from all distances and of the 16 attempts they got on target

two by Garland and one each from Osgood and Cooke provided goals. He could

be blamed for only one, which, on a day when Chelsea, all told, outgunned

Leeds on goal attempts by 26 to six, was an achievement in itself. 'Twice Leeds might have had a consolation goal but Bonetti,

who can seldom have had less to do in a match, foiled Giles and Yorath

- a tireless and for the most part one-man forward line. 'The game had its share of hard play and Cherry and Yorath

of Leeds and Kember of Chelsea had their names taken for what appeared

to be four-point offences under the new disciplinary code. Leeds at least

won on free kicks awarded for fouls - they got 17 against Chelsea's 16.

They may like to reflect, too, that the last time they were beaten by

a margin of four goals in the league was in October 1968 - their title

winning season.' Don Warters in the Yorkshire Evening Post: 'Although

one could have only the highest possible praise for the brave way the

depleted side fought on there was only one conceivable outcome. 'Chelsea, who are being freely tipped to become London's

strongest and most successful side this season, were in luck. You could

almost see a sparkle come into their eyes as they pressed forward eagerly

and incessantly with the intention - and no one can blame them for it

- of taking the fullest possible advantage of United's misfortune. 'In the circumstances, it was difficult to judge the value

of United's two new signings - £100,000 defender Trevor Cherry and £30,000

centre-half Roy Ellam - from Huddersfield Town. Both performed reasonably

well in new surroundings and under the inevitable extra strain which was

placed on the whole side. 'United were virtually finished as an attacking force after

the 24th minute as they had to concentrate their Norman Fox in The Times: 'The rebuilding that Leeds

are doing is not guaranteed by a contractor. Their replacement of Charlton

is inevitable but only at the right time, and with the right man. Undoubtedly,

the confidence of the whole team was broken. 'Ellam had none of Charlton's commanding character and was

never master of Osgood. His former Huddersfield colleague, Cherry, was

not much better. 'It is fairer to view this as Chelsea's success, not Leeds

United's failure. Chelsea were Chelsea, except that they scored more than

their usual number of goals. Their play alternated between such inspired

adventure that it seemed to be showing the path of imagination and skill

to the rest of British football, and such lethargy that one wondered if

they could score more than twice.' After the extraordinary heights reached by United earlier

in 1972, this opening day defeat was a sad wake up call for Don Revie,

hinting at a challenging season to come. The defeat could not be laid

solely at the feet of Roy Ellam, but the former Huddersfield men had been

dreadfully uncertain in his play and seemed to be like a rabbit caught

in the headlights as he was asked to perform in such exalted company.

It was very early days but he certainly convinced nobody that he was the

solution to the vexing question of who would be the long term successor

to Jack Charlton at the heart of the United defence. United's

opening game of the 1972/73 season, at Stamford Bridge against old rivals

Chelsea, left an unfamiliar set of players enduring the most miserable

of afternoons.

United's

opening game of the 1972/73 season, at Stamford Bridge against old rivals

Chelsea, left an unfamiliar set of players enduring the most miserable

of afternoons. yards through the crowd to get on to the pitch.

yards through the crowd to get on to the pitch. yellow

socks rather than their customary white.

yellow

socks rather than their customary white. punching

away a cross from John Hollins and once again denying Cooke.

punching

away a cross from John Hollins and once again denying Cooke. action.

action. tremendous performances but without Harvey, Lorimer had to go into goal

and without Lorimer and Jones the Leeds attack was completely torpedoed.

tremendous performances but without Harvey, Lorimer had to go into goal

and without Lorimer and Jones the Leeds attack was completely torpedoed. efforts on keeping out Chelsea. Paul Madeley did as much as anyone in

this respect, absorbing plenty of pressure and covering a lot of ground.

Lorimer, too, did as well as could be expected between the posts and brought

off several creditable saves. Reaney was another player to stand out under

the heavy pressure.'

efforts on keeping out Chelsea. Paul Madeley did as much as anyone in

this respect, absorbing plenty of pressure and covering a lot of ground.

Lorimer, too, did as well as could be expected between the posts and brought

off several creditable saves. Reaney was another player to stand out under

the heavy pressure.'