|

|

|

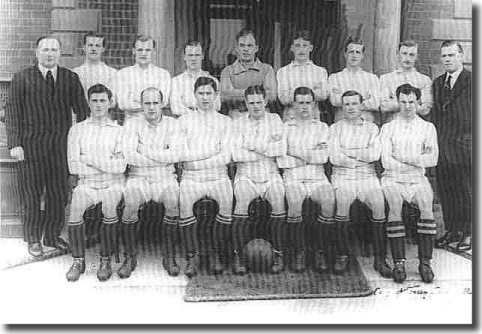

He was born in Kiveton Park, Sheffield, in 1878 and played inside-forward

for Stalybridge, Rochdale, Grimsby, Swindon, Sheppey United and Worksop

between 1897 and 1901 as an amateur, before turning professional with

Northampton. He moved on to Sheffield United and in May 1903 a £300 move

took him to Notts County before he joined Tottenham in March 1905. He

was Spurs' leading scorer with 11 goals in the Southern League in 1905-06.

He was not a great player and his moderate career was notable only for

the flamboyant yellow boots he wore. However, the Northampton directors recognised his tactical skills and

brought him back as player-manager in 1907. He led the Cobblers to the

Southern League championship in his second season before leaving for Leeds

City in 1912. After successfully canvassing for City's re-election to the Football

League, he confidently predicted that he could take the club into Division

One. Chapman understood the need for players of proven achievement, rather

than the hopefuls collected by Scott-Walford. Accordingly, his signings

included the Everton and Ireland goalkeeper Billy Scott, Scottish international

full-back George Law, former England centre-half Evelyn Lintott, who came

from Bradford City and who was soon joined by team mate and inside-left

Jimmy Speirs, and inside-right Jimmy Robertson from Barrow. Stalwarts such as Affleck, Croot and McLeod survived the Chapman revolution.

His new combination was rocked by a 4-0 defeat at Fulham on the opening

day of the 1912/13 season, but soon pulled itself together While the defence

proved alarmingly porous on occasions, as in the 6-2 defeat at Hull on

2 November and when City lost 6-0 at Stockport County on 15 February,

generally the team gave as good as it got. Battle honours included a 5-1

home win over champions Preston, which made the drubbing a week later

at Stockport - who were to finish second from bottom - all the more unsatisfactory. Despite its inconsistency, the verve with which Leeds City played drew

spectators back to Elland Road. When Chapman's team finished sixth, the

average attendance rose from below 8,000 in 1911/12 to more than 13,000

the following year, enabling the club to record a small profit, a remarkable

turnaround from the The nearest he came to achieving the goal of promotion was in 1913/14

when City finished fourth. The club finished with six fewer points than

champions Notts County, but only two behind runners up Bradford Park Avenue.

'Promotion has been denied them but taking into account the resources

of the club, fourth place should be considered satisfactory,' said the

Yorkshire Post. 'Not only have the club attained a higher position

than ever before but receipts and attendances have outstripped any previous

record.' Much of the improvement could be attributed to Chapman's management style:

he was a pioneer in introducing regular team talks and planned tactics

in consultation with the players. He also believed it essential that they

should relax, so introduced a weekly round of golf into the team's training

routine.Despite the disappointment, the directors were pleased because

gate receipts were well up and the club was able to record a £400 profit.

City had been sixth in 1912-13 and hopes were high that 1914/15 would

be the year they finally achieved promotion to the top division, but it

was not be. They slumped back to a very disappointing 15th place. During the War, Chapman worked at a local munitions factory and, although

he returned in 1916, he was suspended

as investigations went on into illegal payments to wartime guest players.

He quit on 16 December 1919 and became industrial manager of an oil and

coke firm in Selby, claiming he had been harshly dealt with by the FA

Commission because he was not in office when the payments were allegedly

made. Only after his appeal was upheld did he move back into management - this

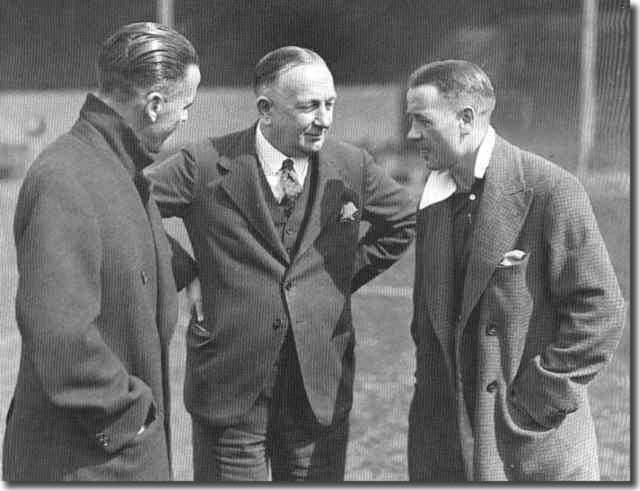

time with Huddersfield. When Chapman joined them in 1920, Huddersfield

Town had little money, few resources and indifferent crowds in a town

devoted to Rugby League. They had joined the League in 1910 and had spent

their first six seasons in the Second Division before being promoted as

runners-up to Tottenham in 1920 in the first season after World War I. After taking over, Chapman led the club on an astonishing sequence of

success, winning the Division One title in 1924 and 1925, and taking the

FA Cup to Leeds Road in 1922. Chapman bought perceptively, welded his

assets together astutely and soon sent out one of the most successful

League sides of all time. It was stubborn, disciplined and highly mobile

with Clem Stephenson, once of Aston Villa, at the heart of everything.

He was a stocky tactician without much pace but his passes were as Chapman led Huddersfield to their first two Championships but then, before

they began their third great season, he surprised the football world by

joining Arsenal - and Arsenal, who had only just avoided relegation the

previous season, finished up as runners-up to Huddersfield. It was hardly

a coincidence. The year that Chapman left Huddersfield for Arsenal - 1925 - was also

the year the offside law was changed. The number of opponents necessary

to keep a player onside was reduced from three to two. Chapman, inevitably,

was the first manager to face the challenge of adapting his tactics to

work to the new law. Arsenal plugged the holes in defence caused by the new law by using an

extra defender. Their centre-half, instead of enjoying an attacking role

in midfield, became a centre-back - the 'stopper' - and an inside-forward

dropped back to make good the link between defence and attack. The day

of the old 2-3-5 formation was over. Now it was 3-3-4. The shape of the

game had changed. The idea itself, however, came from Charlie Buchan and not Chapman. Chapman's

first action as Arsenal manager had been to buy Buchan from Sunderland;

and Buchan, that shrewdest of forwards, suggested before the first match

of the 1925-26 season that Jack Butler, Arsenal's centre-half, should

be used only as a defender. Chapman disagreed. Buchan repeated his idea - without sucess - at every team meeting for

the next five weeks. But in early October Arsenal were beaten 7-0 by Newcastle

at St James's Park - and after the game Buchan said to Chapman: 'I want

to go back to Sunderland. I'm not much use to Arsenal.' Chapman replied:

'Oh no, you're playing against West Ham on Monday. I know what you want

and we'll have a special meeting to discuss it.' Herbert Chapman had finally agreed to Charlie Buchan's request to discuss

a new tactical approach to the game. The meeting took place immediately

following Arsenal's 7-0 hiding by Newcastle at St James's Park in October

1925, in their Newcastle hotel; and Chapman, after a long discussion,

agreed to experiment. Arsenal beat West Ham 4-0 at Upton Park two days

later - and they were on their way to mighty deeds. It was Buchan's idea

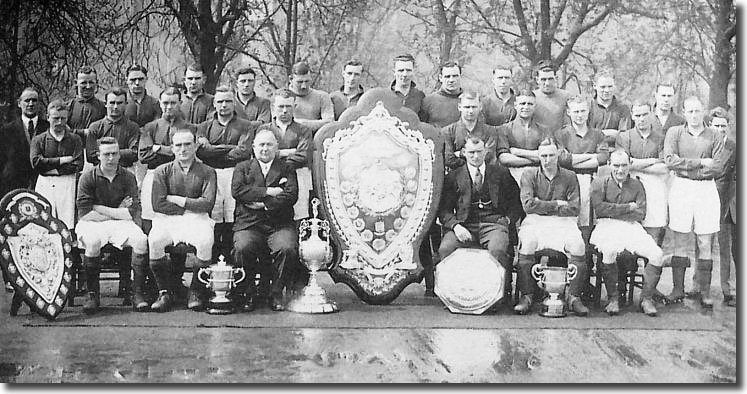

but it was Chapman who refined the system and made it work. Arsenal's first major success was the FA Cup of 1930 and, in the final

at Wembley, they beat Huddersfield 2-0 - Chapman's new creation getting

the better of his old. Huddersfield were ageing while Arsenal were rising

fast, and the following year they won Buchan had retired by now, replaced by David Jack, a vital and elegant

man who scored his goals with sharp-edged charm and even good manners;

and the key role in midfield went to Alex James, an inside-forward of

genius, an imp of a man with buttoned-down sleeves and famously baggy

shorts. Jack of England moved from Bolton for £10,890, the first five-figure

transfer fee, and James of Scotland from Preston for £9,000. The country

raised its hands in horror at such extravagance. Chapman smiled at a couple

of bargains. Chapman led his new Arsenal into the 1930's with huge and

justified confidence. Arsenal's almost complete dominance of the new decade went far beyond

their magnetic accumulation of trophies. A country crippled by recession

and shamed by its dole queues saw the club as a symbol of the prosperity

and privileges of London. Herbert Chapman's team was loved by its own but cordially hated by just

about everyone else. Arsenal were invincible, grandly untouchable and,

always, the team to beat. Their success was even resented in other board-rooms

where complacency and convention ruled; but this was just what the game

needed. Envy became a stimulant. Arsenal's professionalism was studied

and copied. The English game had a Highbury complex - and understandably

so. Arsenal were League Champions five times (1931, 1933-4-5 and 1938), runners-up

in 1932 and third in 1937. They won the FA Cup in 1930 and 1936 and were

beaten finalists in 1932. The first 38 championships had belonged to the

north and midlands but when, at last, the monopoly was broken, Arsenal

did the job properly. There was no television then to flatter and project but Arsenal's players

were household names. Alex James and David Jack, of course; Joe Hulme

and Cliff 'Boy' Bastin, thunder and lightning on the wings; Herbie Roberts,

the shy, red-headed giant who became Arsenal's principal stopper; and

impeccable full-backs such as Tom Parker, George Male and Eddie Hapgood. Some cost a lot of money, others were conjured out of minor football,

but all became essential components of a side which was horribly mean

in defence and cruel in counter-attack. Arsenal's football was sometimes described as 'smash and grab' and often

they were called 'Lucky Arsenal', but Chapman was pointing the way to

the future. His feeling for things to come was remarkable. Chapman once visited an old friend in Austria and returned to talk excitedly

about a night match he had watched. The pitch had been lit by the headlamps

of 40 cars. 'Do you realise," he asked, "that if the same number of lights

were up on 40-foot poles we could play football as if it was daylight?'

Not long after, the press were invited to watch an Arsenal practice match

at night illuminated by dangling lanterns. Chapman got the publicity he

wanted for an idea he was convinced would work. He later watched floodlit

matches in Belgium and Holland - 'cricket with a white ball would have

been possible,' he said. But authority was unimpressed, and it was nearly

20 years before the first official floodlit match was played in England. Chapman was also one of the first men to insist on first-class facilities

for spectators. He tried out numbered shirts five years before there was

approval from the Football League (in 1939); he advocated white balls

and all-weather pitches; he experimented with independent time-keeping

and goal judges; and, the biggest tribute of all to his gift for persuasion,

he had the name of the local underground station changed from Gillespie

Road to Arsenal. Nothing about Chapman was grey or vague. He demanded

power, loyalty, absolute obedience, punctuality at all times and devotion

to the club and profession. In return he was scrupulously fair and true

to his word. Chapman died, suddenly, in January 1934. Despite a chill, and against

advice, he insisted on watching his third team play in a cutting wind

at Guildford. 'I haven't seen the boys for a week or so,' he said. Pneumonia

set in and three days later he was gone. Arsenal still won the championship

that season; and the season after. There is a knowing smile on the face

of the bust of Chapman which now stands in the main entrance hall at Highbury. Herbert Chapman surrounded himself with intelligent footballers, such

as James, Jack, and Buchan. Charles Buchan believed that the secret of

Chapman's greatness was that he 'would always listen to other people and

take advantage of their ideas if he thought they would improve the team

in any way.' Chapman institutionalised his belief in shared discussion

by setting up scheduled meetings for the Arsenal players at midday every

Friday, when the team would discuss both the previous and the upcoming

match. Chapman even had a magnetic model football pitch on a table so

that he could show players exactly what he wanted them to do. Chapman's penchant for tactical planning and ability to transfer his

designs onto the pitch led to his teams earning the label `machine'. This

was heard first in 1910, at Northampton and it was often repeated through

the Arsenal years, where as Harding describes it 'though the In the final analysis, it was Herbert Chapman's boundless desire for

progress that hallmarked his contribution to the development of English

football. He would seemingly utilise any method, regardless of its origin,

to effect the betterment of his teams. He experimented, but he did not

do so blindly, for he possessed the vision and adaptability to incorporate

innovations into his grand designs. History has employed many a superlative

in the attempt to explain the central role of Herbert Chapman in the changes

to the English game, and doubtless his significance will continue to provoke

discussion. Unhappily, however, his influence is perhaps best illustrated

by the events which followed his death. Nobody really took up Chapman's

mantle - and English football stagnated as a result. Whilst the nation

complained that the stopper had a negative impact upon the game, the Hungarians

re-invented the role to momentous effect. It is not inconceivable that Chapman would have been moving in a similar

direction had he lived on. Firstly, he had always sought to keep abreast

of tactical innovation, and there is no reason to assume he would have

ceased doing so. Secondly, he kept a close eye on developments in the

European game, and was a close friend of Hugo Meisl, Chairman of the Austrian

FA. Throughout his managerial career, Chapman had always borrowed ideas if

he considered them worthy and Europe was no exception. His conviction

that 'there is a great future for football by artificial light in England'

was cemented after seeing floodlit matches in Belgium and Holland in 1930.

Chapman had always backed his belief in the importance of learning from

the continentals with actions. As early as 1909, he took his Northampton

team to Germany to play Nuremburg FC and in April 1921 his Huddersfield

side overcame the French Champions, Red Star, 2-0 in Paris. Chapman carried

these excursions The English game was at a crossroads when Chapman died. Despite its status

as one of the most advanced footballing nations, other countries were

catching and surpassing it in many areas. Though there were other progressive

figures in the game, none of their voices carried half the weight that

Chapman's did. He had recognised the need for drastic change, and saw the way forward

in the efficient running of the Italian and Austrian sides. But the English

FA's refusal to learn from these examples and stubborn insistence upon

choosing the national side with a selection committee, were typical of

its unenlightened nature. Nearly a quarter of a century before they were

humbled by the Hungarians at Wembley in 1953, Chapman had predicted a

downturn in England's fortunes if they continued to ignore the advances

being made in the European game. Perhaps it could be said that English

football is still paying the price for not acting on his warning. Herbert

Chapman is one of the greatest British football managers. His success,

ideas and personality revolutionised the game; but he was, more than anything

else, a builder of winning teams. Twice he created a side that was good

enough to win the League Championship in three consecutive seasons - first

Huddersfield (1924-26) and then Arsenal (1933-35). Liverpool (1982-4)

and Manchester United (1999-2001) are the only other clubs to have managed

this hat-trick. Strangely, Chapman was not at the helm for the third win

at either club.

Herbert

Chapman is one of the greatest British football managers. His success,

ideas and personality revolutionised the game; but he was, more than anything

else, a builder of winning teams. Twice he created a side that was good

enough to win the League Championship in three consecutive seasons - first

Huddersfield (1924-26) and then Arsenal (1933-35). Liverpool (1982-4)

and Manchester United (1999-2001) are the only other clubs to have managed

this hat-trick. Strangely, Chapman was not at the helm for the third win

at either club. financial

problems of the previous season. 'Chapman ... has done a tremendous amount

of good work for the club; he has gained the confidence of everybody,'

wrote the Yorkshire Post.

financial

problems of the previous season. 'Chapman ... has done a tremendous amount

of good work for the club; he has gained the confidence of everybody,'

wrote the Yorkshire Post. sweet

as stolen kisses.

sweet

as stolen kisses. the championship for the first time.

the championship for the first time. faces changed, the machine rolled on smoothly, sometimes more efficiently'.

faces changed, the machine rolled on smoothly, sometimes more efficiently'. right through to his Arsenal days, but he believed that they were only

a prelude to a Western European Cup involving the Champions of nations

such as France, Spain, Germany, Scotland and England. Chapman saw such

developments as crucial to the long-term success of English football,

and he cared passionately about his nation's game. In fact, in 1933, despite

objections from selectors, he acted as unofficial manager to the England

team in Italy and Switzerland with considerable success. His tactical

pre-match team talks helped effect a 4-0 victory over a strong Swiss team,

and a 1-1 draw against Italy, in Rome. A year later the Italians were

World Champions and seven Arsenal players were in the England team that

proved what England could achieve, defeating the visitors 3-2 in `the

Battle of Highbury'. Chapman's teams enjoyed considerable success against

continental opposition.

right through to his Arsenal days, but he believed that they were only

a prelude to a Western European Cup involving the Champions of nations

such as France, Spain, Germany, Scotland and England. Chapman saw such

developments as crucial to the long-term success of English football,

and he cared passionately about his nation's game. In fact, in 1933, despite

objections from selectors, he acted as unofficial manager to the England

team in Italy and Switzerland with considerable success. His tactical

pre-match team talks helped effect a 4-0 victory over a strong Swiss team,

and a 1-1 draw against Italy, in Rome. A year later the Italians were

World Champions and seven Arsenal players were in the England team that

proved what England could achieve, defeating the visitors 3-2 in `the

Battle of Highbury'. Chapman's teams enjoyed considerable success against

continental opposition.