|

|

|

History

of the Club - The Leeds City scandal

1919

After the long and dark days of the First World War, the resumption of

official football activity was eagerly anticipated and the new Football

League season kicked off on 30 August 1919. Leeds City started along with

all the others, but were not to see the season out. What was to Charlie Copeland was a full-back who had first played for City on 9 November

1912 in a 4-0 win over Glossop after being signed by Herbert Chapman.

Copeland was in and out of the side over those few seasons before World

War I, but was a regular during the war years. He fell out with the club

over a pay rise and as a result made allegations about illegal payments

being made to wartime guest players. He raised the issue with the football

authorities in July 1919, and even though the practice had been widespread,

neither the FA nor the Football League could ignore such allegations once

formally brought to their attention. But Copeland's actions were only one factor in the wartime problems which

hastened City's demise. The club's troubles began when Herbert Chapman vacated his post as manager

to assist the war effort by taking charge of the Barnbow munitions factory

in East Leeds. Chapman recommended that his assistant, George Cripps,

took control of the club's administration while he was away. Playing matters

became the responsibility of new chairman Joseph Connor and another director. Chapman had been a charasmatic and successful manager over the previous

three years and had bound the club together as a team on and off the field,

but the void he left allowed tension and personality clashes to rise to

the surface. The most problematic conflict was that between Connor and Cripps. The

chairman simply did not rate Cripps and made no secret of the fact. In

fact, he felt so strongly about matters that he threatened to resign if

no action was taken - he maintained that Cripps was mishandling the club's

business affairs and getting things into a mess. The Board sided with

Connor and enlisted the help of an accountant's clerk to look after the

club's books. This happened in 1917. However, despite Cripps having some

health problems, he was made responsible for correspondence and managing

the team. That perverse decision was a mistake, because it only served

to make matters worse. The internal politics continued throughout 1917/18 and it became apparent

that the in-fighting was having a serious impact on the club's well-being.

Indeed, matters had reached such a poor state that the Board was seriously

considering whether there was any real alternative but to pull the plug

on the club. The assets they owned were dwindling fast and they doubted

the wisdom of continuing to throw good money after bad. If the chairman

of the Football League, John McKenna, had not intervened to urge the directors

to battle on, it is likely that Leeds City would have folded there and

then. It might have been better if they had, but it is unlikely that Leeds

United would have ever then come into being. Cripps was as disliked by the club's playing staff as he was by Connor.

Things became so bad at one stage that the club captain John Hampson wrote

to the directors before one match at Nottingham to the effect that if

Cripps were to travel with the team, the players would go on strike. The

crisis was postponed by Connor successfully pleading with Hampson to avert

the strike, arguing that it would spell the end of the club and bring

them all down. But again, it was only a temporary reprieve. Herbert Chapman returned as manager in 1918 and the Board thought that

this might put an end to the internal strife, but this was not to be the

case. They tried to demote Cripps to his former position of assistant,

but he fought the decision bitterly. He felt very badly done by and threatened

to sue the club for wrongful dismissal. Cripps' solicitor was James Bromley,

a former director of the club. Cripps made a claim against the club of

£400 and told Bromley that the club had made illegal payments to players

during the war years. Bromley took speedy action and negotiated a deal between Cripps and the

Board in January 1919. According to Connor, Cripps provided a written

undertaking not to disclose any information relating to the club's affairs

and also promised to pass over all relevant documents in his possession,

including cheque books, pass books and correspondence. He handed all these

documents over to Connor in the presence of the Leeds City's solicitor,

Alderman William Clarke. Clarke sealed all the papers away in a strongbox

in his city centre office. Again according to Connor, Bromley gave his

word of honour that he would not reveal his knowledge of the documents.

In return for all this, Cripps would be given £55, rather less than the

£400 he had sought. Bromley had a different version of events. He maintained that he handed

over a parcel of documents which he had been given by Cripps into the

trust of Clarke, but that the parcel would only be given up if this were

to be agreed by both Connor and himself. He also said that one of the

conditions for the handing over of the parcel was that the Board made

a donation of £50 to Leeds Infirmary. It looked like things had reached an impasse, but matters were shortly

to get very much worse. As City began to assemble their playing staff ready for the 1919/20 season,

the first post-war League campaign, the renewal of Charlie Copeland's

contract was considered. Before the war, Copeland received £3 a week with

a £1 weekly increase when he played in the first team. The board had now

offered Copeland £3 10s (£3.50) for playing in the reserves, and considerably

more if he played for the first team, or they would release him on a free

transfer. The disgruntled Copeland demanded £6 a week and rocked the club by stating

that if he did not get the cash, then he would report City to the Football

Association and the Football League for making illegal payments to players

during the war. City's directors felt they were being blackmailed. At

the risk of forcing Copeland's hand, they ignored his demands and gave

him a free transfer to Coventry. Copeland, who had got hold of certain

documents or at least knew of their contents, carried out his threat in

July 1919 and revealed the alleged irregularities to the authorities. Bromley was also Copeland's solicitor and, though he strenuously denied

it, the club's directors had strong suspicions that it was he who was

feeding Copeland the information which proved so sensitive. Following Copeland's allegations, the Football Association and the Football

League set up a joint inquiry into the matter. The Commission, chaired

by FA chairman, J C Clegg, summoned the club to Manchester on 26 September

1919, to answer the charges. City were represented by Alderman Clarke,

who was asked to present the club books before the inquiry. The Commission,

which included a dozen members of the Football Association and the Football

League, as well as members of the international selection committee, were

stunned when City replied that it was not in their power to do so. Immediately,

the inquiry ordered City to produce the documents by 6 October or face

the consequences. Despite all this off-field controversy, Leeds City had made a solid start

to their new campaign and not even the players could have guessed what

was in store as they set off to play Wolverhampton two days before the

deadline. Because of a rail strike the team went to Molineux by charabanc

and won 4-2, with ace marksman Billy McLeod netting a hat-trick. On the

way home, the City coach gave several stranded people a lift back to the

North and among them was none other than Charlie Copeland. The trip to Wolves was to be City's last game. The Commission's deadline

came and went with no sign of the documents, so the following Saturday's

fixture against South Shields was suspended and after a meeting of the

inquiry team at the Russell Hotel in London, City were expelled from the

Football League and disbanded. League chairman John McKenna announced: "The authorities of the game

intend to keep it absolutely clean. We will have no nonsense. The football

stable must be cleaned and further breakages of the law regarding payments

will be dealt with in such a severe manner that I now give warning that

clubs and players must not expect the slightest leniency." An FA order formally closed the club, leaving everyone associated with

Leeds City shocked and uncomprehending, the unfortunate players out of

a job and City officials to face further punishment. Although there had been no concrete evidence of the alleged illegal payments,

City's silence - whether to protect themselves or a misguided Not even the personal intervention of the Lord Mayor of Leeds, Alderman

Joseph Henry, who offered to take over the club from the directors, could

persuade the inquiry to reconsider and League football came to a halt

in Leeds after just eight games of the 1919-20 season. Five City officials were banned for life - Connor, Whiteman, fellow directors

Mr S Glover and Mr G Sykes and, rather surprisingly, manager Herbert Chapman.

The board promptly resigned, but Chapman earned a reprieve after evidence

was later given that he was working at the munitions factory when the

illegal payments were allegedly made. Connor complained that City were not given a fair hearing by the inquiry

and Alderman Henry also believed that Burslem Port Vale - the club who

had replaced City in the Football League - had brought undue pressure

to bear on the inquiry team, in an effort to get City thrown out, so they

could take their place. Port Vale inherited City's playing record of Played 8, Won 4, Drawn 2,

Lost 2, Goals For 17, Goals Against 10, Points 10. They completed City's

remaining fixtures and finished in 13th place. Bob Hewison, a guest player with City during the war, was asked by the

inquiry to act as secretary during the winding up of the club, a job he

tackled while recovering from a broken leg sustained in 1918/19. Also

helping to sort out the tattered remnants of the club were Alderman Henry

and Leeds accountant W H Platts. Hewison later became Bristol City manager, and became embroiled in another

illegal payments scandal. On 15 October 1938, another joint Football Association

and Football League inquiry into payments made to amateur players fined

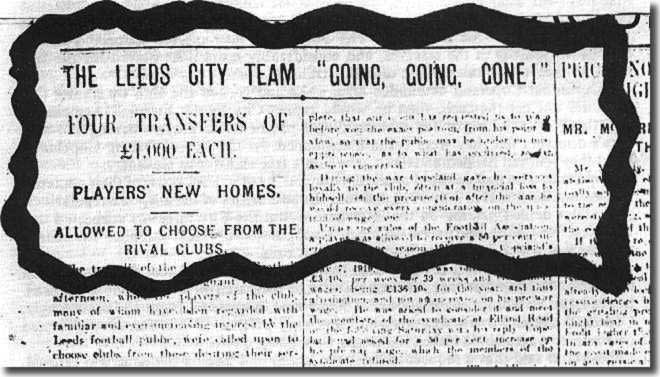

Bristol City 100 guineas and suspended Hewison until the end of the season. Biggest victims of the Leeds closure were the players. The Football League

promised to pay their wages until they could get fixed up with new clubs

and the best way to find them new employers was considered to be by auction,

which was duly held at the Metropole Hotel in Leeds on 17 October. Representatives

from 30 League clubs turned up to haggle over Leeds City's erstwhile assets. It was a humiliating experience for the players as they were sold off

along with the club's nets, goal-posts, boots, kit and physiotherapy equipment.

The entire squad fetched less than £10,150, with fees fixed at between

£1,250 (for star player McLeod) and £100 after would-be purchasers complained

that the original prices were set too high. The Football League, who were

responsible for organising the sale, said that no player should be made

to join any club he did not want to but, with the players anxious to get

back into the action as quickly as possible, the other clubs clearly held

the whip hand. Looking back on the entire shabby episode some years later, John McKenna

revealed he had some sympathy with the plight in which Leeds City found

themselves trapped: "Perhaps others have escaped being found guilty of

malpractices, but if they are found out now we shall not stand on ceremony

or sentiment." However, just as the history of Leeds City came to an abrupt and infamous

conclusion, things took a new twist. Moves were under way to create Leeds

United, a new club which would (eventually) rise triumphantly from the

ashes of this whole sorry affair. become infamously known as The Leeds City Scandal had been rumbling on

for years and it was about to become public knowledge.

become infamously known as The Leeds City Scandal had been rumbling on

for years and it was about to become public knowledge. Bromley

said that he later asked to see a receipt for the donation, but Clarke

told him that Connor was unwilling to enter into any further discussion

with him regarding the club's affairs.

Bromley

said that he later asked to see a receipt for the donation, but Clarke

told him that Connor was unwilling to enter into any further discussion

with him regarding the club's affairs. move to shield players - was deemed to be admission of guilt.

move to shield players - was deemed to be admission of guilt.