Part 2 Ten years in the making - Part

3 Erratic in the extreme - Results and table

Part 2 Ten years in the making - Part

3 Erratic in the extreme - Results and table

The 1913/14 season ended with Leeds City fourth

in the Second Division, a new high for the club. The narrowness with

which they missed out on promotion hinted that they might well fulfil

that aspiration in the following campaign. Unfortunately, events over

the summer months far away in Central Europe saw to it that the term 'campaign',

along with others appropriated by the football world, such as 'victory'

and 'tactics', would now be used more readily in their original context.

The assassination of heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz

Ferdinand, in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914 brought to an angry head a collection

of grumbling disputes that had cast a pall over the continent for years.

The act was the catalyst for a labyrinthine chain of events that would

lead inexorably to the Great War.

Although only third in the line of succession, Ferdinand became heir

apparent following the death of the Emperor's son, Crown Prince Rudolf,

in 1889, and in 1896 that of his own father, Archduke Charles Louis, Emperor

Franz Josef's brother.

Considered arrogant, mistrusting and unrefined by many, Ferdinand was

neither popular nor charismatic. However, the main reason for enmity towards

him was because of suspicion about his intentions after taking power.

He proposed to replace Austro-Hungarian dualism with 'Trialism', a triple

monarchy in which the Slavs would have an equal say alongside the Austrians

and the Hungarians.

Ferdinand was contemplating the idea of even more radical reform: splitting

Austria-Hungary into a number of ethnically and linguistically dominated

semi-autonomous 'states' which would constitute a larger confederation,

to be known as the United States of Greater Austria. Under this plan,

separate languages and cultural identities were encouraged, and the disproportionate

balance of power would be righted. The proposals were fundamentally opposed

by the Hungarian element of the Dual Monarchy, as they would have brought

a significant territorial loss for the Magyars.

The approach was designed to stay the disintegration of the fading Austro-Hungarian

Empire, but Ferdinand's plans set him at odds with the ruling elite.

As Inspector General of the army, Ferdinand accepted an invitation from

General Oskar Potiorek to visit Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia, to inspect

army manoeuvres. Bosnia and Herzegovina were provinces that had been under

Austro-Hungarian administration since 1878. Austria annexed the provinces

outright in 1908, a controversial move which caused unrest and suspicion

amongst other European governments. There was even greater antipathy from

supporters of the idea of a Greater Serbia, who were positively outraged.

Their avowed aim was to absorb the provinces into a Serbian led pan-Slav

state.

Bosnia was consequently a perilous destination and it proved fatal for

Franz Ferdinand. He was murdered on 28 June in Sarajevo by Gavrilo Princip,

a representative of the Black Hand, a Serbian nationalist secret society,

in an attempt to stall his proposed reforms.

Austria was quick to capitalise on the incident, claiming the Serbian

government was the mens rea behind the act. She seized on the opportunity

to rattle her sabres, in a concerted attempt to crush the nationalist

movement in the Balkan states and cement her influence in the region.

Elements within the Austro-Hungarian government had been eagerly seeking

a pretext for offensive action for years, and this was their golden opportunity.

Nationalist pan-Slav agitation within Serbia, which Austria suspected

was encouraged by the Serbian government, could only undermine the Empire's

influence in the Balkans.

The assassination was seen, at least in Austro-Hungarian eyes, as legitimising

what it confidently expected would be a limited war against the manifestly

weaker Serbians.

back to top

Serbia had strong historic links with Russia, the two sharing a common

heritage that had evolved over several centuries. In 1878 Serbia was indebted

to Russian diplomatic support for her success in gaining independence.

The historic alliance was cause for some trepidation on the part of the

Austro-Hungarians.

To assuage their anxieties, Austria sought assurances from her own ally,

Germany, that she would provide support should Russia enter the dispute.

The Germans were delighted to offer their aid: a conflict outside the

national borders ideally suited their own purposes and they offered an

unconditional guarantee of support on 5 July.

Left wing parties in Germany, particularly the Social Democratic Party,

made heavy gains in the national elections of 1912. The German Government

was still dominated by the Prussian Junkers, who feared the rise of the

Left. The German historian, Fritz Fischer, argued that they deliberately

sought an external war as a distraction, which would stoke up patriotic

support for the Government.

Such dark political intrigue relied on a calculated gamble regarding

the responses of other governments. With an element of undoubted complacency,

provocative action was considered a risk well worth taking.

Germany offered what became known as "the blank cheque" to Austria on

6 July. The German Kaiser, Wilhelm II, promised unconditional support

for Austria regardless of whatever sanction she intended to impose upon

Serbia.

It was clear that Germany was prepared for a limited conflict with France

and Russia; she hoped to avoid war with Britain, gambling  that

the British would shy away from war in an attempt to retain neutrality.

that

the British would shy away from war in an attempt to retain neutrality.

On 23 July, Austria presented Serbia with an ultimatum demanding that

the assassins be brought to justice. A reply was demanded within 48 hours,

in the full expectation that the terms would be rejected, thereby providing

the pretext for war. British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Gray commented

that he had 'never before seen one state address to another independent

state a document of so formidable a character', though the government

sought to mediate throughout July, attempting desperately to remain neutral.

The Serbian Prime Minister, Nikola Pasic, appealed to Russia for help.

On 25 July, while waiting for assurance of support, Pasic agreed to all

Austro-Hungarian demands bar one: he was unable to hand over the three

men who had engineered the assassination as it 'would be a violation of

Serbia's Constitution and criminal in law'. The Austrians were caught

off guard by the compliance of the response, so disconcerted that they

concealed the communication for two days from the Germans. The Kaiser

commented that the reply was 'a great moral victory for Vienna, but with

it every reason for war disappears'.

Nevertheless claiming they were not satisfied with Serbia's response

to their ultimatum, Austria declared war on 28 July. Russia immediately

announced mobilisation of her army in defence of Serbia. On 31 July the

Germans demanded that Russia halt her mobilisation within 12 hours; they

also demanded that France should remain neutral and hand over border fortresses

as a guarantee. The Germans knew these were unacceptable terms and the

inevitable rejection allowed them to declare war on Russia on 1 August.

Two days later, Germany declared war on France and invaded Belgium so

as to reach Paris by the shortest possible route.

A Triple Entente between Russia, France and Britain had long been in

place; in addition Britain had a commitment, dating back to 1839, to defend

Belgian neutrality. The British government, led by Prime Minister Hebert

Asquith, felt that they had to draw a line in the sand and gave Germany

an ultimatum to get out of Belgium by midnight, 3 August.

It is thought that Germany would have backed away from war had Britain

given a prompter hint of her resolve. Believing that the British would

stay out of the coming conflict and limit themselves to diplomatic protests,

Germany proceeded under the belief that war would be fought solely with

France and Russia.

The British government, in the person of Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward

Gray, attempted to mediate throughout July, reserving at all times its

right to remain aloof from the dispute. It was only as the War began that

the British position solidified into support for Belgium.

Asquith had a simple choice: he could turn a blind eye to a war in mainland

Europe that might have little impact on Britain if she stood as a neutral,

or he could mark himself with the British public as a man of principle

who held firm against the perceived bullying of Germany. Future Prime

Minister Winston Churchill described the scene in London in the hours

that led to the declaration of war.

'It was eleven o'clock at night - twelve by German time - when the ultimatum

expired. The windows of the Admiralty were thrown wide open in the warm

night air. Under the roof from which Nelson had received his orders were

gathered a small group of admirals and captains and a cluster of clerks,

pencils in hand, waiting. Along the Mall from the direction of the Palace

the sound of an immense concourse singing 'God save the King' floated

in. On this deep wave there broke the chimes of Big Ben; and, as the first

stroke of the hour boomed out, a rustle of movement swept across the room.

The war telegram, which meant, 'Commence hostilities against Germany,'

was flashed to the ships and establishments under the White Ensign all

over the world. I walked across the Horse Guards Parade to the Cabinet

room and reported to the Prime Minister and the Ministers who were assembled

there that the deed was done.'

back to top

Asquith addressed a packed House of Commons, saying, 'We have made a

request to the German Government that we shall have a  satisfactory

assurance as to the Belgium neutrality before midnight tonight. The German

reply to our request was unsatisfactory.'

satisfactory

assurance as to the Belgium neutrality before midnight tonight. The German

reply to our request was unsatisfactory.'

Asquith explained that he had received a telegram from the German Ambassador

in London who, in turn, had received one from the German Foreign Secretary.

Officials in Berlin wanted the point pressed home that German forces went

through Belgium to avoid the French doing so in an attack on Germany.

Berlin had "absolutely unimpeachable information"'that the French planned

to attack the German Army via Belgium. Asquith stated that the Government

could not "regard this in any sense a satisfactory communication… We have,

in reply to it, repeated the request we made last week to the German Government

that they should give us the same assurance with regard to Belgium neutrality

as was given to us and to Belgium by France last week. We have asked that

a reply to that request and a satisfactory answer to the telegram of this

morning should be given before midnight.'

Nothing of the sort was received and the Foreign Office released this

statement:

'Owing to the summary rejection by the German Government of the request

made by His Majesty's Government for assurances that the neutrality of

Belgium would be respected, His Majesty's Ambassador in Berlin has received

his passport, and His Majesty's Government has declared to the German

Government that a state of war exists between Great Britain and Germany

as from 11pm on August 4th.'

Britain's declaration of war against Germany brought the support of British

Commonwealth countries like Australia, Canada, India and New Zealand,

alongside Japan, who had a military agreement with Britain.

Thus, what had commenced as a little local difficulty escalated rapidly

into global conflict. The expansionist leanings of Otto von Bismarck,

first Prime Minister of Prussia and then Chancellor of the German Empire,

and Kaiser Wilhelm II had rendered such an outcome inevitable.

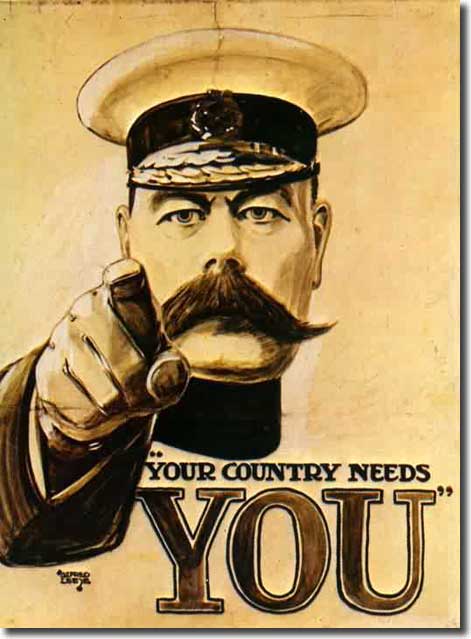

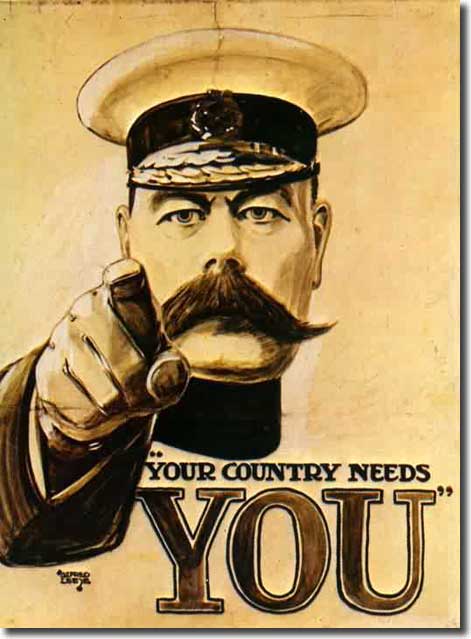

On the outbreak of war, Britain had just under 250,000 regular troops.

It was clear that many thousands more would be needed to defeat the Germans

and on 7 August, Lord Kitchener, the War Minister, launched a recruitment

campaign, calling for men aged between 19 and 30 to sign up. This was

very successful, with an average of 33,000 men joining every day. Three

weeks later the upper limit for recruiting was raised to 35 and by the

middle of September over 500,000 men had volunteered. At the beginning

of the War the army had strict regulations about who could become soldiers.

Men joining the army had to be at least 5ft 6in tall with a chest measurement

of 35 inches. However, these specifications were loosened up in order

to get more men to join the armed forces.

British forces were sent to help stop the German advance across France,

and few thought that they would not return before Christmas. But by 1915

the opposing sides had dug themselves into a system of trenches that zigzagged

along the Western Front, a battlefield extending some 450 miles across

Belgium and North-Eastern France to the border of Switzerland. They remained

deadlocked in this trench warfare until 1918.

Stephen Studd in Herbert Chapman: Football Emperor: 'Britain was

the only country entering the War without compulsory military service.

As the football season approached, the question arose whether the League

competition should be suspended so that players and officials could be

free to volunteer for the war effort. It was a situation organised football

had never had to face before, and there was no precedent on which to base

a decision. Flying in the face of public opinion and patriotic fervour,

the authorities decided to go ahead with games as planned.

'The reaction was one of violent denunciation. Newspapers said they would

not report matches and carried a barrage of irate letters. A Yorkshire

Post reader suggested that the King should resign as patron of the

Football Association. At the same time the FA "urged players and

spectators who are physically fit and otherwise able to join the Army",

and several players did so, but the Football League insisted that "in

the interests of the people of this country, football ought to be continued."

back to top

'The League's attitude reflected the traditional belief that the ordinary

citizen need not be affected by war. Wars had been fought before by the

regular Army, and this one, it was supposed, would be the same: it would

be over in a few months, if not weeks. So League teams kicked off in the

usual way, while the guns blazed across the Channel. After a few weeks

newspapers lifted their ban on match reports, and, while the War was waged

on the front page, the struggle for league points gathered pace on the

back.'

The announcement by the football authorities that the football programme

was to continue provoked a fierce backlash. Criticism was vociferous and

clubs were accused of selfishness and conspiring with the enemy; the Dean

of Lincoln wrote to the FA of 'onlookers who, while so many of their fellow

men are giving themselves in their country's peril, still go gazing  at

football'.

at

football'.

Many senior players quit their clubs to volunteer for the armed forces,

but the League decided to carry on with their programme. The football

authorities contributed to war charities, and assisted in the recruitment

of volunteers.

As most League players were professionals and thus tied contractually

to their clubs, they could only join the forces if the clubs agreed to

cancel their contracts. If they refused, the men could be sued by their

clubs for breach of contract. Some newspapers suggested that those who

did not join up were 'contributing to a German victory', piling moral

pressure on players.

Under considerable pressure, the Football Association eventually backed

down and called for football clubs to release all unmarried professional

footballers to join the armed forces. The FA also agreed to work closely

with the War Office to encourage football clubs to organise recruiting

drives at matches.

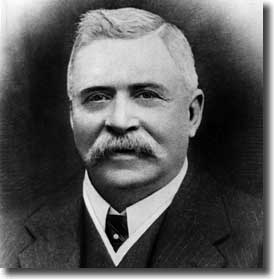

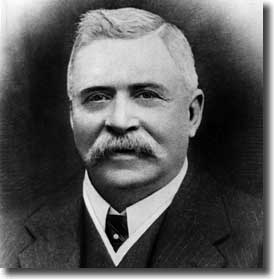

At Elland Road, Leeds City's management invited Lord Mayor Edward Brotherton

and local MPs to address spectators at the end of the season's opening

game in the hope of getting them to sign up. The club's official Receiver,

Tom Coombs, came up with the idea and

got support from Captain Kelly, the local head of army recruitment. Coombs

undertook to provide the necessary support staff and resources to administer

the exercise.

The Athletic News responded angrily to the general criticism of

football: 'The whole agitation is nothing less than an attempt by the

ruling classes to stop the recreation on one day in the week of the masses...

What do they care for the poor man's sport? The poor are giving their

lives for this country in thousands. In many cases they have nothing else...

These should, according to a small clique of virulent snobs, be deprived

of the one distraction that they have had for over thirty years.'

On 31 August, the Consultative Committee of the Football Association

issued the following statement: 'The Football Association earnestly appeals

to the patriotism of all who are interested in the game to help in all

possible ways in support of the nation in the present serious crisis,

and particularly to those able to render personal service in the Army

and Navy which are so gallantly upholding our national honour.

'To those unable to render personal service the Association would appeal

for their generous support of funds for the relief and assistance of dependents

of those who are engaged in serving their country.

'The Football Association will contribute £1,000 to the Prince of Wales'

War Fund and £250 to the Belgian Relief Fund.

'It was stated that of about a million players only 7,000 were professionals

and of those only 2,500 were exclusively engaged for football. The opinion

of the War Office was in favour of continuing football. It was resolved

that clubs should give every facility for the temporary release of players

who desired to join the colours.'

President John McKenna reported on the views of the League Management

Committee: 'Any national sport which can minimise the grief, help the

nation to bear the sorrows, relieve the oppression of continuous strain,

and save the people at home from  panic

and undue depression is a great national asset which can render lasting

service to the people.

panic

and undue depression is a great national asset which can render lasting

service to the people.

Just as we look hour after hour for the latest news from the theatres

of war, our vast armies in the field will week by week look for papers

from home, and insofar as their mind may be temporarily distracted from

the horrors of war and the intense strain of days and weeks of almost

unrestricted fighting, much will be done to give them fresh heart, fresh

hopes and a renewed vitality for the work before them.

'At home our clubs were in a helpless position, as their contracts, entered

into with all the formality of legal contracts, must be performed as far

as possible. We feel that the advice offered by politicians, the Press,

and commercial authorities that business should be carried on as usual

is sound, well considered and well reasoned advice. We therefore, without

the slightest reservation, appeal to the clubs, the Press and the public

that our great winter game should pursue its usual course.

back to top

'Every club should do all in its power to assist the war funds. Every

player should specially train to be of national service at least in national

defence. Whilst we unreservedly authorise the due fulfilment of the League

programme, we must all accept to the full every obligation that we can

individually and collectively discharge for our beloved country and our

comrades in arms who in this fight for righteousness and justice, at the

risk of their lives, have answered to duty's call.'

In the first week of September, FA secretary Fred Wall (later Sir Frederick)

wrote to the War Office stating that the FA was prepared to request all

their members to stop the playing of matches if the War Office was of

the opinion that such a course would assist them in their duties.

The War Office expressed gratitude to the FA for their assistance in

obtaining recruits for the army and in placing football grounds at their

disposal, but went on, 'The question whether the playing of matches should

be entirely stopped is more a matter for the discretion of the Association,

but the Council realise the difficulties involved in taking such an extreme

step, and they would deprecate anything being done which does not appear

to be called for by the present situation.

'Should your Association decide to continue the playing of matches, the

Council trust that arrangements will be made so as not to interfere with

the facilities at present afforded to the recruiting authorities. The

Council also suggest that the Association might take all steps in their

power to press the need of the country for recruits upon spectators who

are eligible for enlistment, and they would further venture to suggest

that some portion of the gate money might be set aside for the charitable

relief of the families and dependents of all soldiers and sailors who

are serving in the present war.'

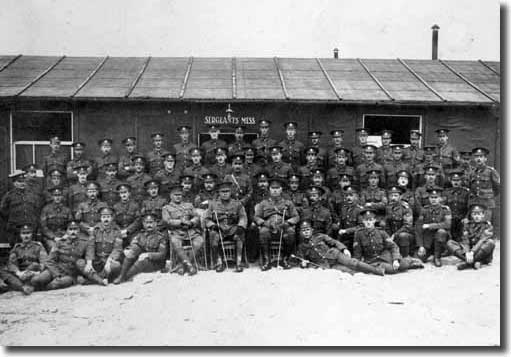

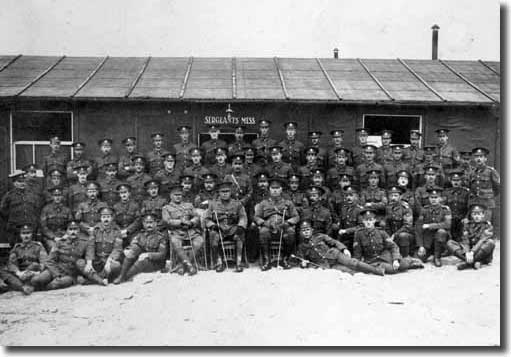

The public of Leeds played their full part in the war effort. The leeds-pals.com

website carries the tale of the Leeds Pals,  The

15th (service) Battalion (1st Leeds) The Prince of Wales' Own (West Yorkshire

Regiment).

The

15th (service) Battalion (1st Leeds) The Prince of Wales' Own (West Yorkshire

Regiment).

'The general idea of a Pals' Battalion was that the volunteers would

join and serve with friends, relatives, workmates and colleagues, giving

a feeling of comradeship that had never been seen before.

'Most major towns and cities … raised Pals' Battalions. To be accepted

to these elite units, the recruits were to pass certain requirements.

Education and intelligence were considered paramount to being accepted

in the majority of cases. It was not only businessmen and local dignitaries

however, that were recruited; Great Britain supplied its finest and for

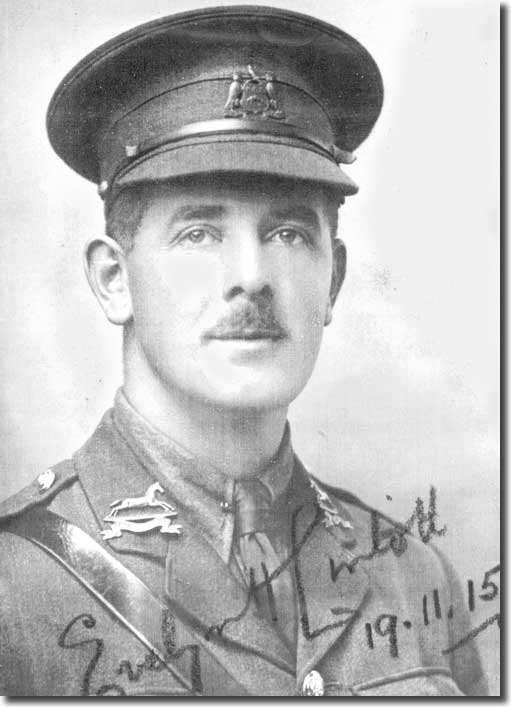

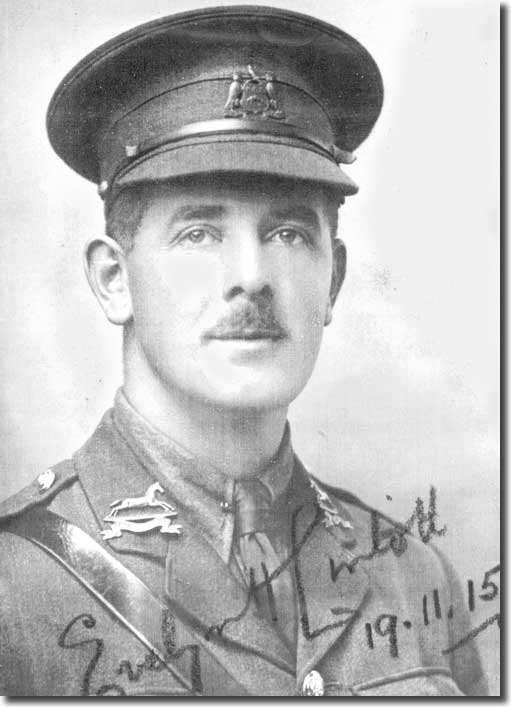

Leeds this meant several famous sports men also. Evelyn

Lintott (later to be commissioned), a Leeds City and international

half-back footballer, along with Morris Flemming, another footballer,

were considered a bonus to the Battalion. Yorkshire cricketers featured

among the recruits who included Major Booth, Arthur Dolphin and Roy Kilner.

Team sports did not offer the only possibilities but also athletes such

as Albert Gutteridge and George Colcroft were eager to be a part of something

so patriotic and unique that it may never be seen again.

'By the 8th of September 1914 the Battalion had enlisted some 1,275 men

after rejecting many on medical grounds. This number at the time was considered

to be complete although the final number of Leeds Pals eventually rose

to approximately 2,000.

'France was expected to be the Pals' first destination but this was not

so. Early December 1915 saw the first group of Pals set sail for Suez.

Inevitably France was to be for many of the Pals their final destination.

'On March 1st 1916 the Pals set sail for Marseilles as the Battle of

the Somme became imminent. The battle was to prove tragic for the Leeds

Pals. Twenty-four Pals' officers went over the top with their men on that

fateful day, 1st July 1916. Lieutenant Major Booth, the famous cricketer,

and Evelyn Lintott, the footballer, were just two of the many that were

killed in action. Approximately 750 out of 900 involved in the Somme died.

'The patriotism shown by the people of Leeds at the outbreak of war with

Germany was reflected in the City Council's approach to, and involvement

in, the raising of the 1st Leeds Battalion. Quite a few family members

of the raising committee were already serving or would later serve as

officers with the Pals. Its first Colonel was Walter Stead, a prominent

local solicitor and Council member, who had made the original application

to Lord Kitchener for permission to raise the Leeds Battalion. This had

been seconded in a telegram sent to Kitchener by Edward Brotherton, the

Lord Mayor of Leeds, who personally bore the cost of raising and outfitting

the Battalion. He also placed his personal fortune in the hands of the

Council as a guarantee against the costs Leeds might incur in the War.

'Alderman Charles Wilson JP became the Quartermaster. Alderman and Solicitor

Arthur Willey's son Tom and James Wardle's son James were commissioned

into the Pals as Lieutenants, along with Maurice Bickersteth, son of the

Vicar of Leeds. The zeal and patriotism of the Council was then applied

to finding a site large enough to accommodate upwards of  a

thousand men, at a pace unheard of today, land at Breary Banks in Colsterdale

owned by the waterworks department and being used for the building of

a new reservoir was placed … at the battalion's disposal.

a

thousand men, at a pace unheard of today, land at Breary Banks in Colsterdale

owned by the waterworks department and being used for the building of

a new reservoir was placed … at the battalion's disposal.

back to top

'The time spent at Colsterdale was for most, the best time of their lives.

Carefree days with good food, good accommodation and good company, their

civilian skills were soon being put to military use. When material started

arriving for the construction of more solid accommodation, recruits with

the necessary backgrounds were employed on hut building, men with country

backgrounds were soon catching the rabbits that were so abundant around

Colsterdale, enabling the battalion cooks to serve up regular meals of

rabbit stew, so regular that one Pal, Walter Astle, on returning home

after the War, refused to eat rabbit for the rest of his life.'

The country's professional footballers were pilloried for what was regarded

as their unpatriotic reluctance to enlist for the war effort. Spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk:

'On 6 September 1914, Arthur Conan Doyle (the creator of Sherlock Holmes

and himself a goalkeeper with the amateur side, Portsmouth AFC), appealed

for footballers to join the armed forces: "There was a time for all

things in the world. There was a time for games, there was a time for

business, and there was a time for domestic life. There was a time for

everything, but there is only time for one thing now, and that thing is

war. If the cricketer had a straight eye, let him look along the barrel

of a rifle. If a footballer had strength of limb, let them serve and march

in the field of battle."

'Frederick Charrington, the son of the wealthy brewer who had established

the Tower Hamlets Mission, attacked the West Ham United players for being

effeminate and cowardly for getting paid for playing football while others

were fighting on the Western Front. The famous amateur footballer and

cricketer, Charles B Fry, called for the abolition of football, demanding

that all professional contracts be annulled and that no one below forty

years of age be allowed to attend matches.

'William Joynson Hicks established the 17th Service (Football) Battalion

of the Middlesex Regiment on 12th December, 1914. This group became known

as the Football Battalion. According to Frederick Wall, the secretary

of the Football Association, the England international centre-half, Frank

Buckley, was the first person to join the Football Battalion. At first,

because of the problems with contracts, only amateur players like Vivian

Woodward and Evelyn Lintott were able to sign up.

'As Frank Buckley had previous experience in the British Army he was

given the rank of Lieutenant. He eventually was promoted to the rank of

Major. Within a few weeks the 17th Battalion had its full complement of

600 men. However, few of these men were footballers. Most of the recruits

were local men who wanted to be in the same battalion as their football

heroes. For example, a large number who joined were supporters of Chelsea

and Queens Park Rangers who wanted to serve with Vivian Woodward and Evelyn

Lintott.

'At the beginning of the 1914/15 football season, Hearts was Scotland's

most successful team, winning eight games in succession. On 26th November

1914, every member of the team joined the British Army. This event had

a major impact on the public and inspired footballers and their fans to

enlist. Seven members of the Hearts team never returned to Scotland. Three

of the men, Harry Wattie, Duncan Currie and Ernie Ellis, were killed on

the first day of the Somme offensive. Another member of the team, 22-year-old

Paddy Crossan, was so badly injured that his right leg was labelled for

amputation. He pleaded with the German surgeon not to operate. He told

him: "I need my legs - I'm a footballer." He agreed to his request

and managed to save his leg. Crossan survived the War but later died as

a result of his lungs being destroyed by poison gas.

'By March 1915, it was reported that 122 professional footballers had

joined the battalion. This included the whole of the Clapton Orient first

team. Three of them were later killed on the Western Front. At the end

of the year Walter Tull, who had played for Tottenham Hotspur, Northampton

Town and Glasgow Rangers, joined the battalion. Major Frank Buckley soon

recognised Tull's leadership qualities and he was quickly promoted to

the rank of Sergeant.

'On 15th January 1916, the Football Battalion reached the front line.

During a two-week period in the trenches, four members of the battalion

were killed and 33 were wounded. This included Vivian Woodward who was

hit in the leg with a hand grenade. The injury to his right thigh was

so serious that he was sent back to England to recover.

back to top

'Woodward did not return to the Western Front until August 1916. The

Football Battalion had taken heavy casualties during the Somme offensive

in July. This included the death of England international footballer,

Evelyn Lintott. The battle was still going on when Woodward arrived but

the fighting was less intense. However, on 18th September a German attack

involving poison gas  killed

14 members of the battalion.

killed

14 members of the battalion.

'Major Frank Buckley was also seriously injured during this offensive

when metal shrapnel had hit him in the chest and had punctured his lungs.

George Pyke, who played for Newcastle United, later wrote: "A stretcher

party was passing the trench at the time. They asked if we had a passenger

to go back. They took Major Buckley but he seemed so badly hit, you would

not think he would last out as far as the Casualty Clearing Station."

Buckley was sent to a military hospital in Kent and after operating on

him, surgeons were able to remove the shrapnel from his body. However,

his lungs were badly damaged and he was never able to play football again.

'William Angus played for Glasgow Celtic before joining the 8th Battalion,

Highland Light Infantry. On 11th June, Lieutenant James Martin led a covert

bombing raid on an embankment in front of the German trenches. The party

was spotted and the enemy detonated a large mine hidden in the earth.

Martin was one of the causalities of the explosion. At first, he was thought

to be dead, but he was seen to move as he pleaded for water from the Germans.

The soldiers responded by throwing a grenade over the parapet.

'As soon as he heard what had happened, William Angus volunteered to

attempt a rescue of the man who also came from Carluke. At first this

was vetoed by senior officers who considered it a suicidal mission. Angus

replied that it did not matter much whether death came now or later. Eventually,

Brigadier General Lawford gave permission for Angus to try and save Martin.

'A rope was tied around William Angus so that he could be dragged back

if killed or seriously wounded. Angus managed to reach Martin by crawling

through No Man's Land without being detected. He gave him a drink of brandy

before attaching the rope to Martin. Angus then tried to carry Martin

back to the safety of the British trench 70 yards away. However, once

upright, Angus was soon seen by the Germans and he came under heavy fire.

Angus was hit and he fell to the ground. For the next few minutes he sheltered

Martin with his own body. Angus then signalled to the British troops to

pull Martin to safety. He then set off at right angles to the trench,

drawing the enemy fire away from Martin. Despite being hit several times,

he managed to drag himself back to the trenches. His injuries resulted

in him losing his left eye and part of his right foot.

'His commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Gemmill later wrote that

"no braver deed was ever done in the history of the British Army."

For this act of bravery William Angus became the first professional footballer

to be awarded the Victoria Cross. Angus' citation read: "For most

conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty at Givenchy, on 12th June 1915,

in voluntarily leaving his trench under very heavy fire and rescuing an

officer who was lying within a few yards of the enemy position. Lance

Corporal Angus had no chance of escaping the enemy's fire when undertaking

this very gallant action, and in effecting the rescue he sustained about

forty wounds from bombs, some of them being very serious."

'It has been argued that Donald Bell, a defender with Bradford City,

was the first professional footballer to join the British Army after the

outbreak of the War. He enlisted as a Private but by June, 1915 he had

a commission in the Yorkshire Regiment. Two days after his marriage in

November 1915, he was sent to France.

'Second Lieutenant Bell took part in the Somme offensive. On 5th July

he stuffed his pockets with grenades and attacked an enemy machine gun

post. When he attempted to repeat this feat five days later he was killed.

He was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross for his action.'

Such acts of bravery and selflessness are legion in the history of the

Great War and it seems more fitting to remember them than the accusations

of cowardice and self-preservation which were laid at the doors of those

who were considered, even then, pampered and overpaid dilettantes.

Part 2 Ten years in the making - Part

3 Erratic in the extreme - Results and table

back to top

Part 2 Ten years in the making - Part

3 Erratic in the extreme - Results and table

Part 2 Ten years in the making - Part

3 Erratic in the extreme - Results and table that

the British would shy away from war in an attempt to retain neutrality.

that

the British would shy away from war in an attempt to retain neutrality. satisfactory

assurance as to the Belgium neutrality before midnight tonight. The German

reply to our request was unsatisfactory.'

satisfactory

assurance as to the Belgium neutrality before midnight tonight. The German

reply to our request was unsatisfactory.' at

football'.

at

football'. panic

and undue depression is a great national asset which can render lasting

service to the people.

panic

and undue depression is a great national asset which can render lasting

service to the people. The

15th (service) Battalion (1st Leeds) The Prince of Wales' Own (West Yorkshire

Regiment).

The

15th (service) Battalion (1st Leeds) The Prince of Wales' Own (West Yorkshire

Regiment). a

thousand men, at a pace unheard of today, land at Breary Banks in Colsterdale

owned by the waterworks department and being used for the building of

a new reservoir was placed … at the battalion's disposal.

a

thousand men, at a pace unheard of today, land at Breary Banks in Colsterdale

owned by the waterworks department and being used for the building of

a new reservoir was placed … at the battalion's disposal. killed

14 members of the battalion.

killed

14 members of the battalion.