|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FA Charity Shield - Wembley Stadium - 67,000

Scorers: Cherry - Liverpool won 6-5 on penalties

Leeds United: Harvey; Reaney, McQueen, Hunter, Cherry; Lorimer, Bremner, Giles, E Gray; Clarke (McKenzie), Jordan

Liverpool: Clemence; Smith, Thompson, Hughes, Lindsay; Heighway, Cormack, Hall, Callaghan; Keegan, Boersma

Liverpool and Leeds had vied for supremacy of English football

ever since Leeds returned to the First Division in 1964. In the

previous season, the Anfield club had given the runaway First

Division leaders the fright of their lives in the Spring when

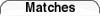

the title had seemed all but wrapped up by Christmas. The Charity Shield confrontation marked the last game in charge of Liverpool

for Bill Shankly and the debut at the helm of the Elland Road club for

the brash Brian Clough. Long-time manager

Don Revie had departed to take over the England team and the Leeds

board had shocked the footballing world by appointing one of the fiercest

critics of both the team and the manager to succeed him. Clough, in fact, had intended to kick off his reign in a bizarre way,

as he explained: 'The television pictures from Wembley, for the traditional

curtain-raiser of the Charity Shield, should have been different. They

showed dear old Bill Shankly leading out his magnificent Liverpool side

and alongside him, followed by the Leeds team with the glummest faces

ever seen at such an occasion, there was me. Much as I admired Shanks,

and I loved the man, I didn't want to march from the tunnel at the head

of the Leeds United side that day - I asked Don Revie to lead them out,

instead. 'Yes, I was prepared and eager to relinquish the honour of that managerial

march onto the Wembley turf which was, and still is, the dream and ambition

of everyone who enters the profession. I had not won the title with Leeds

- Revie had. I phoned Revie on the day of the match. 'This is your team,'

I told him, 'you lead them out at Wembley.' Apart from anything else,

I thought it was a decent thing to do, a nice gesture towards a man who

had just won the League title - the toughest test of management anywhere

in the world. But he was not to be tempted. '"Pardon?" he said, obviously taken aback by my offer. "You've

got the job now, Brian. I'm not coming down to lead them out. It is your

privilege." 'There should be a feeling of pride and immense satisfaction when you

make that walk from the tunnel to the touchline at what is still the most

famous old stadium in the world. There always was on the umpteen occasions

I did it with my Nottingham Forest team. I wonder how many managers have

taken their teams to Wembley as often as I did? Not many. 'I was proud - and, to use Revie's word, privileged - to walk out alongside

Shankly. In fact, I remember turning towards him and clapping him as we

walked. But there was no sense of togetherness with those who walked behind

me.' Ever the showman, Shankly led out Liverpool for the last time

- he'd announced his resignation that summer - alongside Clough.

One of the funnier sights of a nasty afternoon was Clough, the

young pretender, trying to engage the old master in friendly banter

as the teams entered the arena. Shankly completely blanked him. Leeds and Liverpool had had some bitter battles down the years,

but it is doubtful whether there had ever been an angrier encounter

than there was that day. The trouble started early in the game. There were niggling fouls

from the off with Billy Bremner and Johnny Giles nipping at the

heels of a Liverpool team that Shankly had rebuilt from its eminence

in the Sixties. They were about to take a vice like grip on the

English game while Leeds were on the wane. The United side, which

was for some reason very intense and irritable, had obviously

set out to win the game at all costs. The arrival of the abrasive

Clough had disturbed the Leeds camp and they were in no mood to

contribute to a frivolous showpiece event. Early in the game, a Liverpool player had pressed Giles from

behind and clipped his ankle - the Irishman was never one to take

such treatment lying down and turned round and lashed out at the

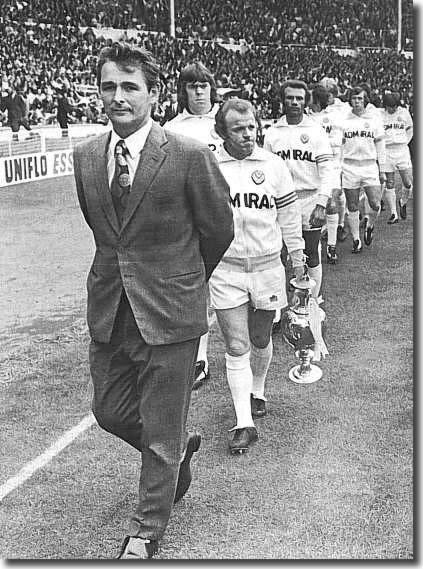

offender. He got a booking and a stiff lecture for his trouble. That was only the precursor to the main event of the afternoon, however,

as the play became ever more fraught and fractious. It was probably six

of one and half a dozen of the other, but Clough, with his customary black

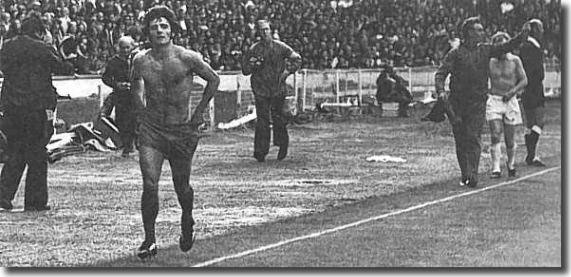

and white 'Bremner seemed intent on making Kevin Keegan's afternoon an absolute

misery. He kicked him just about everywhere - up the arse, in the balls

- until it became only a matter of time before a confrontation exploded.

There is only so much any man can take. Eventually, inevitably, Keegan

snapped - and they were both sent off, Keegan whipping off his shirt and

flinging it to the ground as he went. It was a stupid gesture, but I could

understand the man's anger and frustration. It was the action of a player

who felt he had been wronged, not only by an opponent but by a referee

who had failed to stamp out intimidation before it reached the stage of

retaliation. Keegan will have regretted his touchline tantrum immediately.

A Liverpool shirt was not something to be thrown away. 'Keegan was a victim, not a culprit, that day at Wembley. The double

dismissal was all down to Bremner. Keegan was an innocent party who had

been pushed beyond the limit by an opponent who appeared determined to

eliminate him from the match, one way or another. I told Bremner afterwards

that he had been responsible for the confrontation. He should have been

made to pay compensation for the lengthy period Keegan was suspended.' The two of them had clashed in the Leeds area and they started brawling.

They had to be pulled apart and separated by players and officials and

were then sent from the field. The Times was typical in its condemnation:

'That, in itself, would have been enough to disgust. But both men compounded

the felony as they began the long walk to the dressing rooms by shamelessly

stripping off the shirts they should have been proud to wear, Bremner,

indeed, throwing his petulantly to the ground, where it lay crumpled like

a shot seagull until cleared away by a linesman. It was a disgusting scene,

the volcanic climax of three earlier affrays which had seen Smith and

Giles booked. 'Sadly, Keegan could have been the man of the match. Leeds patently realised

this by half time and seemed intent on eliminating him by fair means or

foul. They chose the unfair method, finally goading the little Liverpool

man into hot headed retaliation with all the dire consequences for those

who consider themselves above the law. 'Never before had Wembley witnessed such a disgrace as two British players

for the first time were dismissed from the stadium. It made child's play

of the Rattin affair in the World Cup of 1966.' The offence resulted in a lengthy ban for the two players and it was

October before Bremner played again, by which time Clough's ill-fated

period at Leeds had ended. Clough's one eyed version of events was coloured

by his nightmare experience at the club and if truth be known, the clash

was the culmination of a fierce and long running The game itself was a thoroughly ill tempered affair and good football

was in very short supply. With the players too busy kicking each other

to notice, the match petered out to a 1-1 stalemate. Leeds had been chasing

the game since Phil Boersma opened the scoring in the 20th minute, but

Trevor Cherry headed home an equaliser after 70 minutes. The goals were

just a distracting sideshow to the violence. The game went to penalties and, with the scores balanced precariously

at 5-5 in sudden death, Leeds bizarrely chose their keeper David Harvey

to go next. Harvey duly obliged by thumping the ball over the bar. Ian

Callaghan smashed home the winner for Liverpool, but the match will be

remembered only for the ridiculous sight of Keegan and Bremner's bare-chested

outrage. There were some very hysterical newspaper articles in the days that followed

the game and some of the holier than thou members of the media were all

for kicking both clubs out of the First Division. As it was, Keegan and

Bremner were banned for 11 matches in all and fined £500 apiece, but no

further action was taken. It was the first Charity Shield match ever to be shown on television,

and the chairman of the disciplinary committee, Vernon Stokes, admitted

that the punishment might not have been quite so severe if the match had

not been played at Wembley and shown to the viewing millions. The Times was fairly typical of the mood of the day in its pointed conclusion:

'If clubs are held responsible for the behaviour of their supporters,

so should they be for their players. The final responsibility and remedy

rest with all directors and managers and they also should share the penalty.

The harder they are hit where it hurts most, the better - either through

their pockets, with heavy fines, or by deducting points from a club's

League total. That might make everybody think twice. 'One way or another, a solution has to be found if the game is to survive

as a respectable spectacle. The final sanction may be for all reasonable

people simply to stay away and let ritual violence destroy itself.' It was a sorry day in the history of football. The shock of the incident

and the appalling relationship with the new manager reverberated around

Elland Road and Leeds made an awful start to their defence of the League.

They won just four points from their first seven games, form which cost

Clough his job and Leeds the title in a season when Derby County won through

with one of the lowest points totals ever. The

1974 Charity Shield match was a turning point in English football, pitching

together two of the biggest rivals in the game, Leeds United and Liverpool,

as the Football Association tried to revive the status of the season's

traditional curtain raiser by moving it to Wembley. It was the first time

for years that champions had actually faced Cup winners in the game and

the rivalry between England's two biggest clubs made it a particularly

high profile occasion.

The

1974 Charity Shield match was a turning point in English football, pitching

together two of the biggest rivals in the game, Leeds United and Liverpool,

as the Football Association tried to revive the status of the season's

traditional curtain raiser by moving it to Wembley. It was the first time

for years that champions had actually faced Cup winners in the game and

the rivalry between England's two biggest clubs made it a particularly

high profile occasion. vision,

was clear about who he felt was the guilty party in the clash just after

the hour which will remain the lasting memory of the game: 'Billy Bremner's

behaviour was scandalous, producing one of the most notorious incidents

in Wembley history. It was as if the players were offering grounds for

all my criticism that they had resented so much.

vision,

was clear about who he felt was the guilty party in the clash just after

the hour which will remain the lasting memory of the game: 'Billy Bremner's

behaviour was scandalous, producing one of the most notorious incidents

in Wembley history. It was as if the players were offering grounds for

all my criticism that they had resented so much. midfield battle for control, but the repercussions for Leeds were immense.

midfield battle for control, but the repercussions for Leeds were immense.