|

|

|

History

of the Club - Origins of Football

How

the game began and reached Britain

Football, like the poor and taxation, has been around

for centuries, although many of its Geoffrey Green: 'What has been revealed, though,

by the researches of a certain Professor at Cambridge University, H A

Giles, is that there was some form of football in China long before the

Romans of Julius Caesar brought their game of harpastum to Britain. 'The Chinese, indeed, point to one of the earliest

known references to football in the period belonging to the mythical Yellow

Emperor of the third Millennium BC. If there is no hard proof to support

that, at least there is evidence about the game being in existence in

the Third and Fourth Centuries BC. At that point it was part of the military

training of the period, and the evidence of it can be seen in a military

textbook of twenty-five chapters dating some 2,000 years ago from the

Han dynasty. The History of the Han Dynasty spans the period 206 BC to

AD 25, and it is there that there is discovered a true reference to some

early stirring, by the use of the words tsu chu. Tsu meant

"to kick with the foot"; chu was "the ball made

of leather and stuffed". 'Japan, too, can point to a game called kemari

which has been played there for some fourteen centuries. The ground was

roughly 14 square metres in size. In the North West corner there stood

a pine tree, a willow to the South East, a cherry tree to the North East

and a maple to the South West. Eight players made up the game, which consisted

of kicking a ball from one to another. The suggestion is that some religious

ceremony was attached to this.' There are stories of variations being played all

over Europe in medieval times - in Italy in 1555 a form of street football

was being played in Venice and from 1595, also in Florence, where it was

known as calcio. In France, Germany, Holland and Russia there are

references to football from around the same time. The British version of the game is thought to have

been inspired by the Romans, when they imported harpastum (a Roman word

for 'handball'). It was an individual ball game with physical contact

a significant feature, and was developed from the rather more genteel

episkyros of the Ancient Greeks. The Roman legions may well have

played the game as they awaited their return to sunnier climes. Back in

Italy, the game had developed into calcio by the Sixteenth Century. Harpastum was a game something akin to Rugby

and was used as a form of military training to improve the physical fitness

of Roman legionnaires. It was known as the Small Ball Game to distinguish

it from other games involving much larger balls. The Harpastum ball was

made from a stitched leather skin, stuffed with chopped sponges or animal

fur, and was around 8 inches in diameter. It involved two sides of approximately

the same strength competing in a restricted space, striving to take a

hollow ball beyond a certain mark at either end of the field of battle.

The methods they employed in doing so were no holds barred and included

wrestling. Footballnetwork.org: 'The game of football generally

flourished in England from around the 8th Century onwards. The game was

incredibly popular with the working classes and there were considerable

regional variations of the game throughout the country. 'The level of violence within the game was astonishing.

Players were kicked and punched regularly by opponents. In addition to

any personal injury that occurred, countless property items were destroyed

in the course of a match. Fields were often ruined, as were fences and

hedges. Damage also occurred to people's houses and businesses within

the main streets of the village (or wherever the game travelled in its

course). 'For people living within the cities, football was

still an alien concept and considered to be a "rural custom".

However, in the second half of the 12th Century football had established

itself in London. By 1175 an annual competition had been established in

the capital and every Shrove Tuesday the game created huge interest and

gained further popularity. 'The future development of the urban game is not

well known but some early records do mention the violent nature of the

game within cities - there is even a mention of a player being stabbed

to death by an opponent! Records also point to women being involved in

the game during the 12th Century.' The first description of a football match in England

was written by William FitzStephen in about 1170. He records that while

visiting London he noticed that 'after dinner all the youths of the city

goes out into the fields for the very popular game of ball.' He points

out that every trade had their own football team. 'The elders, the fathers,

and the men of wealth come on horseback to view the contests of their

juniors, and in their fashion sport with the young men; and there seems

to be aroused in these elders a stirring of natural heat by viewing so

much activity and by participation in the joys of unrestrained youth.' A few centuries later another monk wrote that football

was a game 'in which young men ... propel a huge ball not by throwing

it into the air, but by striking and rolling it along the ground, and

that not with their hands but with their feet.' The writer strongly condemned

the game claiming it was 'undignified and worthless' and that it often

resulted in 'some loss, accident or disadvantage to the players themselves.' One manor record, dated 1280, states: 'Henry, son

of William de Ellington, while playing at ball at Ulkham on Trinity Sunday

with David le Ken and many others, ran against David and received an accidental

wound from David's knife of which he died on the following Friday.' In

1321, William de Spalding was involved in a similar incident: 'During

the game at ball as he kicked the ball, a lay friend of his, also called

William, ran against him and wounded himself on a sheath knife carried

by the canon, so severely that he died within six days.' There are a number

of other recorded cases during this period of footballers dying after

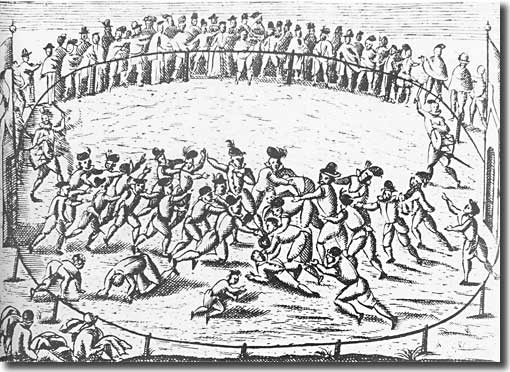

falling on their daggers. Geoffrey Green: 'At that period youths of the city

of London chased footballs in Smithfield; later football players made

their mark at Covent Garden, Cheapside and the Strand, Fleet Street, Moorfields

and Lincoln's Inn Fields in London. Prints still survive as proof of this. 'In other parts of the country, Derby, Nottingham,

Dorking and Kingston-on-Thames arose as points in the spread of the game.

'At Derby, Ashburton and elsewhere there grew up

the fierce Shrove Tuesday games. They were scarcely games, of course.

They resembled a free for all battle more than anything else, but they

represented a traditional beginning. Here was all in wrestling combined

with unarmed combat as sections of the community chased the ball through

the streets. Thus there arose the name 'mob football', out of which finally

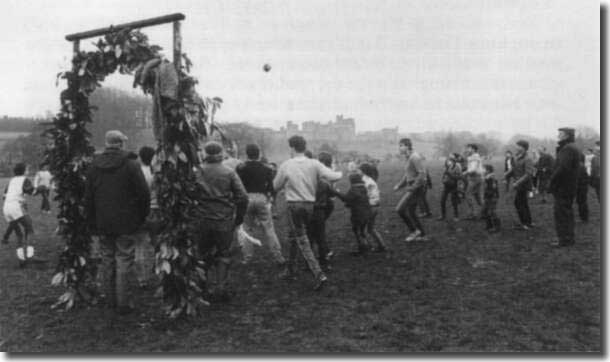

developed the game we now know. 'The Shrove Tuesday match at Derby, in fact, survives

to this day. It is traditional. It began there when the young men of the

parish of All Saints challenged those of the parish of St Peter. Since

all men over the age of eighteen took part, trying to force the ball from

one parish into the other - each parish representing the goal - the teams,

as it were, often numbered over 500 apiece. Two marks were made, one at

Nun's Mill, the other at Gallows Balk on the Ormaston Road, and the object

was to force the ball to one or other of these.' The Shrove Tuesday contest is one of the earliest

recorded indigenous football games, being first reported in AD 217. Even then, the game had spread far and wide: Dorset's

Corfe Castle and Scone in Scotland were among other venues where an annual

Shrove Tuesday fixture took place. At Chester, a leather ball was introduced,

the City Hall and the hall at Rodehoe being the goals for the game. Few,

however, played on pitches such as the one recorded in Cornwall in 1602,

whose goals were three to four miles apart and the teams were each comprised

of the menfolk of two or three neighbouring parishes. London was at the

forefront of these mob football games. One really curious thing about the game in England

is the way that it has survived and even thrived in spite of fierce and

formal opposition from the powers that be. By the reign of Edward II, football had become so

popular, with so many people joining in with games in the streets that

the merchants of London protested to the King that it was an obstacle

to their trade and should be banned. On April 13 1314, Edward II issued

a decree forbidding the game: 'For as much as there is great noise in

the city caused by hustling over large balls ... from which many evils

might arise, which God forbid: we command and forbid on behalf of the

King, on pain of imprisonment, such game to be used in the city in future.' The edict had an initial impact, but football soon

re-emerged as a popular pastime. Indeed, it was so popular that it was

feared that the royal subjects were spending too much time honing their

ball skills at the expense of their dexterity with the longbow. In 1349,

Edward III issued another banning order, reasoning that 'the skill at

shooting with arrows was almost totally laid aside for the purpose of

various useless and unlawful games'. The pattern continued. Forty years later, Richard

II passed a similar statute forbidding 'all playing at tennise, football

and other games called corts, dice, casting of the stones, kailes and

other such importune games'. Henry IV had to reissue the same commandment

in 1401. In 1457 James III of Scotland decreed that 'football

and golfe be utterly cryed down and not to be used', while in 1491 his

successor commanded that 'in no place of this realme ther be used futeball,

golfe or other sik unprofitable sportes'. Henry VIII also banned the game

and even rendered it a penal offence by statute for anyone to keep a house

or ground devoted to such things as cards, dice and football. Elizabeth I decreed that 'no foteballe play to be

used or suffered within the City of London'. During her reign, the grand

jury of Middlesex County found 'that on the said day at Ruyslippe, County

of Middlesex, Arthur Reynolds, husbandman (with five others, all of Ruyslippe),

Thomas Darcye, of Woxbridge, yeoman (with seven others), with unknown

malefactors to the number of one hundred, assembled themselves unlawfully

and played a certain unlawful game called foote-ball, by means of which

unlawful game there was amongst them a great affray likely to result in

homicides and serious accidents ...' Wilfried Gierhardt: 'The passion for football was

particularly exuberant in Elizabethan times. An influence that most likely

played a part in intensifying the native popularity for the game came

from Renaissance Italy, particularly from Florence, but also from Venice

and other cities that had produced their own brand of football known as

calcio. lt was certainly more organised than the English equivalent and

was played by teams dressed in coloured livery at the important gala events

held on certain holidays in Florence. It was a truly splendid spectacle.

In England the game was still as rough and ungracious and lacking in refinement

as ever, but it did at this time find a prominent supporter who commended

it for other Much of the reason for the sustained official opposition

was the general opinion that football was 'a very vulgar and unfashionable

pastime', enjoyed mainly by commoners. For centuries, any such game that

was 'not connected in any way with knightly skill was considered unfit

for a gentleman of equestrian rank'. In 1608 the Manchester Lete Roll of October 12 contained

a resolution: 'That whereas there has been heretofore great disorder

in our towne of Manchester, and the inhabitants thereof greatly wronged

and charged with makinge and amendinge of their glasse windows broken

yearelye and spoyled by a companye of lewd and disordered psons using

that unlawfull exercise of playinge with the ffote-ball in ye streets

of ye sd towne breakinge many men's windowes and glasse at their plesures

and other great enormyties. Therefore we of this jurye doe order that

no manner of psons hereafter shall play or use the footeball in any street

within the said towne of Manchester, subpoend to evyeone that shall so

use the same for evye time.' Unsurprisingly the Puritans were equally concerned,

regarding football as a form of unseemly revelry. In 1683, the author

Stubbes wrote thus: 'Lord remove these exercises from the Sabbath. Any

exercise which withdraweth from godliness, either upon the Sabbath or

any other day, is wicked and to be forbidden. Now who is so grossly blind

that seeth not that these aforesaid exercises not only withdraw us from

godliness and virtue, but also hail and allure us to wickedness and sin?

For as concerning football playing I protest unto you that it may rather

be called a friendly kind of fight than a play or recreation - a bloody

and murdering practice than a fellow sport or pastime. For doth not everyone

lye in wait for his adversary, seeking to overthrow him and punch him

on his nose, though it may be on hard stones, on ditch or dale, on valley

or hill, or whatever place so ever it be he care not, so he have him down;

and that he can serve the most of this fashion he is counted the only

fellow, and who but he? So that by this means sometimes their necks are

broken, sometimes their backs, sometimes their legs, sometimes their arms,

sometimes their noses gush out with blood, sometimes their eyes start

out, and sometimes hurt in one place, sometimes in another ... Football

encourages envy and hatred ... sometimes fighting, murder and a great

loss of blood.' A writer called Moor at the end of the Eighteenth

Century described the way the game was played at that time: 'Each party has two goals, ten or fifteen yards

apart. The parties, ten or fifteen on a side, stand in line facing each

other at about ten yards distance midway between their goals and that

of their adversaries. An indifferent spectator throws up a ball the size

of a cricket ball midway between the confronted players and makes his

escape. The rush is to catch the falling ball. He who first can catch

or seize it speeds home, making his way through his opponents and aided

by his own sidemen, If caught and held, or rather in danger of being held,

for if caught with the ball in possession he loses a snotch, he throws

the ball (he must in no case give it) to some less beleaguered friend

more free and more in breath than himself, who, if it be not arrested

in its course or be jostled away by the eager and watchful adversaries,

catches it. Then he in like manner hastens homeward, in like manner pursued,

annoyed and aided, winning the notch or snotch if he contrive to carry

or throw it within the goals. At a loss or gain of a snotch a recommencement

takes place. When the game is decided by snotches seven or nine are the

game, and these if the parties are well matched take two or three hours

to win. Sometimes a large football was used; the game was then called

"kicking camp"; and if played with shoes on, "savage camp".' Geoffrey Green: 'There is no doubt that Puritanism

put a damper on football 'Up to the age of the Puritans, football certainly

was a national sport. But from the Restoration onwards, for something

like two hundred years, there was a steady decline in its popularity until

an athletic revival in the early Nineteenth Century; though for the latter

part of this period, football became a school sport. However, from the

declining references made to the game by the Eighteenth Century writers,

it seems that football at that point had lost much of its national popularity. 'In the reign of Charles II, however, it appears

that football still held sway in London, understandably enough, because

Charles himself was a great patron of most athletic sports. In 1691, indeed,

Charles II attended a match played between his own servants and the Duke

of Albemarle's - the first recorded instance of royal patronage of football.' About this time, there was something of a change

in the nature of the English game. J R Witty: 'During Cromwell's supremacy,

many Royalists left England, and in their enforced absence overseas some

of the Cavaliers saw at Florence and Sienna in Italy a game called calcio.

This was a football match between two teams, limited in number and played

in a restricted space, with the players clothed in distinctively coloured

uniforms. Play was governed by recognised rules, with prescribed forms

of etiquette and exchange of courtesies between the contesting teams.

It had some slight resemblance to the kind of game played by Roman soldiers

centuries before. 'The game itself was both a spectacle and an entertainment

at which ladies could be present. They wore or displayed coloured favours

as team supporters, and the houses round the field were gaily decorated

with similar colours, which added to the gaiety of the scene. It was not

unlikely that these Cavaliers with their sense of colour were impressed,

and that they brought back to this country from their exile a liking for

this more spectacular and more disciplined form of the game. 'Certainly, when a match was staged in 1681 between

the servants of the King and those of the Duke of Albemarle, the whole

lay out was not of the mob game type. A painting on wood is extant, which

I have seen; and my opinion is that it pictures a match of the more modern

type. Teams of equal numbers dressed in highly coloured distinctive clothing

oppose one another on a field more oval than rectangular in shape. At

either end is a wooden fort with an open doorway guarded by a custodian;

near each is a uniformed drummer and another man carrying something like

an axe, evidently to notch or score any wins. The ball is being kicked

about in attempts to drive it through one of the doorways. Around the

ground, the mock battlefield, are the spectators, some obviously of the

lower classes, others in more splendid clothing, whilst in a decorated

pavilion at one side are some evidently quite distinguished people. 'One thing is outstanding: this game was in quite

a different category from the old undisciplined kind.' At the beginning of the 1800s, however, football

was in decline as a direct result of the earlier Puritan oppression. Joseph

Strutt, a great historian of English sports, writing in 1801, said of

football: 'The game was formerly much in vogue among the common people,

though of late years it seems to have fallen into disrepute and is but

little practised.' He continued, 'When a match at football is made,

two parties, each containing an equal number of competitors, take the

field, and stand between two goals, placed at the distance of eighty or

an hundred yards the one from the other. The goal is usually made with

two sticks driven into the ground, about two or three feet apart. The

ball, which is commonly made of a blown bladder, and cased with leather,

is delivered in the midst of the ground, and the object of each party

is to drive it through the goal of their antagonists, which being achieved

the game is won. The abilities of the performers are best displayed in

attacking and defending the goals; and hence the pastime was more frequently

called a goal at football than a game at football. When the exercise becomes

exceeding violent, the players kick each other's shins without the least

ceremony, and some of them are overthrown at the hazard of their limbs.' In 1815 Hone provided this description in his Everyday

Book of Football Day at Kingston-on-Thames, when travellers to Hampton

Court could see upon entering Teddington 'all the inhabitants securing

the glass of their front windows from the ground to the roof, some by

placing hurdles before them, and some by nailing laths across the frames.

At Twickenham, Bushy and Hampton Wick they were all engaged in the same

way. 'At about 12 o'clock the ball is turned loose to

those who can kick it. There were several balls in the town of Kingston

and of course several parties. I observed some persons of respectability

following the ball; the game lasts about four hours, when the parties

retire to the public houses.' Geoffrey Green: 'This, at least, shows that though

football may have declined it was not extinguished. It When Cambridge University introduced football into

their curriculum at the turn of the Seventeenth Century, even its detractors

had to reconsider. But with a welter of different rules proliferating,

these games were strictly intramural affairs. With the advent of the Industrial

Revolution, few of the downtrodden working classes had the time or energy

to pursue such a physically demanding sport - and football passed into

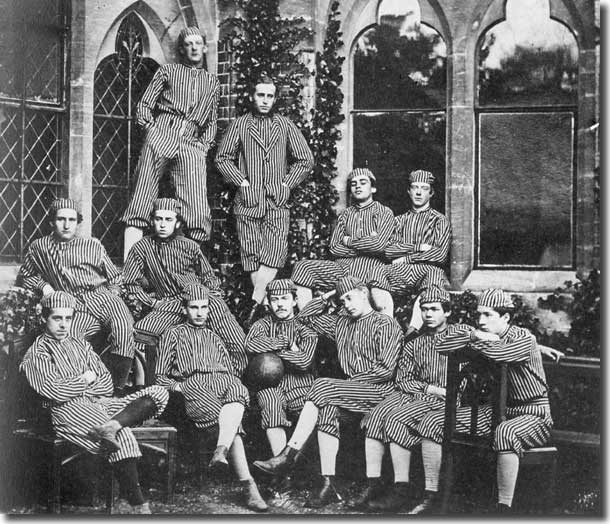

the hands of the leisured upper classes. Each public school, it seemed, had its own special

set of rules, often influenced by the physical characteristics of the

location in which the game was played. At Charterhouse, where the stony

cloisters provided the pitch for 20 players a side, the ball was played

by feet alone; at Rugby, handling (but not running in possession) was

positively encouraged. Harrow played a recognisable form of today's game

on grass, 11 players making up a team, while Winchester's goals extended

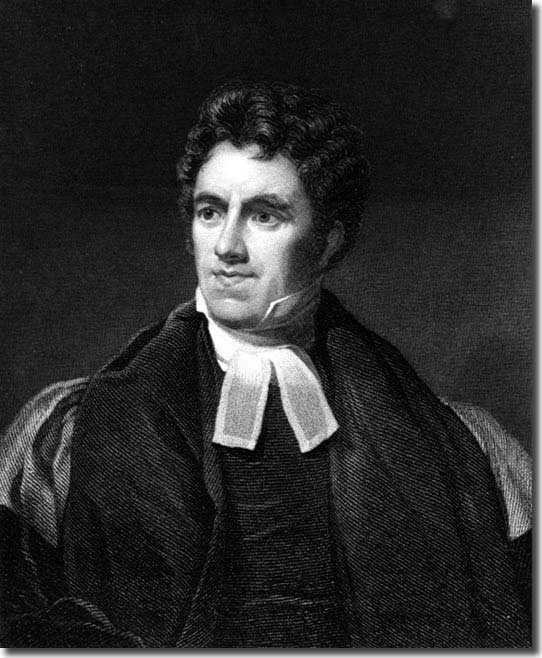

the entire length of the goal line, rather like Rugby's try line today. Thomas Arnold was appointed headmaster of Rugby

in 1828. He had a profound and lasting effect on the development of public

school education in England. Arnold introduced mathematics, modern history

and modern languages and introduced the prefect system to keep discipline.

He modernised the teaching of Classics by directing attention to literary,

moral or historical questions. Although Arnold held strong views, he made

it clear to his students they were not expected to accept those views,

but to examine the evidence and to think for themselves. Arnold also had a good method for 'encouraging senior

boys to exercise responsible authority on behalf of the staff'. He argued

that games like football provided a 'formidable vehicle for character

building'. Each school had its own set of rules and style of

game. In some schools the ball could be caught, if kicked below the hand

or knee. If the ball was caught near the opposing goal, the catcher had

the opportunity of scoring, by carrying it through the goal in three standing

jumps. Rugby, Marlborough and Cheltenham developed games

that used both hands and feet. The football played at Shrewsbury and Winchester

placed an emphasis on kicking and running with the ball (dribbling). School

facilities also influenced the rules of these games. Students at Charterhouse

played football within the cloisters of the old Carthusian monastery.

As space was limited the players depended on dribbling skills. Whereas

schools like Eton and Harrow had such large playing fields available that

they developed a game that involved kicking the ball long distances. According to one student at Westminster, the football

played at his school was very rough and involved a great deal of physical

violence: 'When running ... the enemy tripped, shinned, charged with the

shoulder, got down and sat upon you... in fact did anything short of murder

to get the ball from you.' Football games often led to social disorder. As

Dave Russell pointed out in Football and the English (1997), football's

'habit of bringing the younger element of the lower orders into public

spaces in large numbers (was) increasingly seen as inappropriate and,

indeed, positively dangerous in an age of mass political radicalism and

subsequent fear for public order.' Action was taken to stop men playing football in

the street. The 1835 Highways Act provided for a fine of 40s for playing

'football or any other game on any part of the said highways, to the annoyance

of any passenger.' In 1840 soldiers had to be used to stop men playing

football in Richmond. Six years later the Riot Act had to be read in Derby

and a troop of cavalry was used to disperse the players. There were also

serious football disturbances in East Molesey, Hampton and Kingston-upon-Thames. Although the government disapproved of the working

classes playing football, it continued to be a popular sport in public

schools. In 1848 a meeting took place at Cambridge University to lay down

the rules of football. As Philip Gibbons points out in Association

Football in Victorian England (2001), 'The varying rules of the game

meant that the public schools were unable

to compete against each other.' Teachers representing Shrewsbury, Eton,

Harrow, Rugby, Marlborough and Westminster, produced what became known

as the Cambridge Rules. One participant explained what happened: 'I cleared

the tables and provided pens and paper ... Every man brought a copy of

his It was eventually decided that goals would be awarded

for balls kicked between the flag posts (uprights) and under the string

(crossbar). All players were allowed to catch the ball direct from the

foot, provided the catcher kicked it immediately. However, they were forbidden

to catch the ball and run with it. Only the goalkeeper was allowed to

hold the ball. He could also punch it from anywhere in his own half. Goal

kicks and throw ins took place when the ball went out of play. It was

specified that throw ins were taken with one hand only. It was also decided

that players in the same team should wear the same colour cap (red and

dark blue). It was inevitable that this situation would not

last. The catalyst for change and standardisation was William Webb Ellis'

legendary dash with the ball in 1823 that eventually gave rise to the

game of Rugby. This form of football broke ranks with soccer in 1848,

when a 14 man committee at Cambridge University defined the game as permitting

handling only to control the ball. Further rules then decided upon stated that the

goals should consist of two posts. Fouls were defined as tripping, kicking

or holding, and an offside rule insisting on three men between the passer

and the opposing goal was instituted. When the Sheffield Cricket Club permitted matches

to be played on their Bramall Lane pitch in the late 1850s, it seemed

symbolically as if football had finally attained respectability. In the

process, Sheffield could legitimately lay claim to the status of Britain's

oldest football club. Their players emanated from the city's Old Collegiate

School. Games against local rivals such as Hallam (formed 1857) attracted

600 spectators. Such an organisation was by no means confined to

the North. The Blackheath Club formed in Kent in 1857, while others formed

in the 1850s included Hampstead Heathens. The Old Harrovians were ex-pupils

of Harrow School, while other Harrow old boys founded Wanderers, originally

named Forest Football Club after their ground in Epping Forest near Snaresbrook.

Notts County, established in 1862, were the first of the future Football

league clubs to be founded. With such grassroots activity flourishing,

the time was ripe for the organising zeal of the Victorians to bring order

and systems into play and provide the necessary framework for the game

of football to move forward as an organised competitive sport. earliest forms were far removed from today's version of the game. There

are records of examples in China, as long ago as 200 BC, as well as others

in Ancient Greece and the Roman Empire.

earliest forms were far removed from today's version of the game. There

are records of examples in China, as long ago as 200 BC, as well as others

in Ancient Greece and the Roman Empire. Games

were normally violent and disorganised affairs with any number of players

- it was not uncommon for 1,000 people to play in a single game. By the

11th Century, games were often played between rival villages and the "pitch"

could be an incredibly large area. The "pitch" was not a defined

size with a parameter, but included streets, fields, village squares and

anything else that got in the way!

Games

were normally violent and disorganised affairs with any number of players

- it was not uncommon for 1,000 people to play in a single game. By the

11th Century, games were often played between rival villages and the "pitch"

could be an incredibly large area. The "pitch" was not a defined

size with a parameter, but included streets, fields, village squares and

anything else that got in the way! At

Kingston, indeed, there grew up the tradition that the right of playing

was gained for the inhabitants by the bravery of their forebears who defeated

the Danes in a marauding battle, and having cut off the head of the Danish

general, kicked it about in triumph.

At

Kingston, indeed, there grew up the tradition that the right of playing

was gained for the inhabitants by the bravery of their forebears who defeated

the Danes in a marauding battle, and having cut off the head of the Danish

general, kicked it about in triumph. reasons

when he saw the simple joy of the players romping after the ball. This

supporter was Richard Mulcaster, the great pedagogue, head of the famous

schools of Merchant Taylor's and St. Paul's. He pointed out that the game

had positive educational value and it promoted health and strength. He

claimed that all that was needed was to refine it a little and give it

better manners. His notion was that the game would benefit most if the

number of participants in each team were limited and, more importantly,

there were a stricter referee.'

reasons

when he saw the simple joy of the players romping after the ball. This

supporter was Richard Mulcaster, the great pedagogue, head of the famous

schools of Merchant Taylor's and St. Paul's. He pointed out that the game

had positive educational value and it promoted health and strength. He

claimed that all that was needed was to refine it a little and give it

better manners. His notion was that the game would benefit most if the

number of participants in each team were limited and, more importantly,

there were a stricter referee.' for

a spell. The political hold of this creed was short. But the effect it

had upon the nation put a large stop not only to Sunday football, but

to the playing of the game on other days also.

for

a spell. The political hold of this creed was short. But the effect it

had upon the nation put a large stop not only to Sunday football, but

to the playing of the game on other days also. was

merely in a state of dormancy. It soon picked up again and it did so during

the 1850s at a time when the period of 'muscular Christianity' came into

vogue under the lead given by the great public schools of the land. Thus

it is true to say that while the "manly game of football" has

flourished for centuries in these islands, it was the public schools who

took it from the streets and the fields, civilised it, brought law and

order and system to it (though most of the schools had their own rules

differing from each other), until finally it was shaped and polished and

unified under one set of rules drawn up for national acceptance by the

Football Association in 1863. Nor can we forget the Universities of Cambridge,

and later Oxford, who were to take their place in this developing process

of creating one set of laws so that all could play and enjoy the same

game.'

was

merely in a state of dormancy. It soon picked up again and it did so during

the 1850s at a time when the period of 'muscular Christianity' came into

vogue under the lead given by the great public schools of the land. Thus

it is true to say that while the "manly game of football" has

flourished for centuries in these islands, it was the public schools who

took it from the streets and the fields, civilised it, brought law and

order and system to it (though most of the schools had their own rules

differing from each other), until finally it was shaped and polished and

unified under one set of rules drawn up for national acceptance by the

Football Association in 1863. Nor can we forget the Universities of Cambridge,

and later Oxford, who were to take their place in this developing process

of creating one set of laws so that all could play and enjoy the same

game.' school

rules, or knew them by heart, and our progress in framing new rules was

slow.'

school

rules, or knew them by heart, and our progress in framing new rules was

slow.'