|

|

|

History

of the Club - Organising the game

The

Victorians bring order

It was in England in the second half of the Nineteenth Century that football

began Football was promoted by several progressive and reforming headmasters,

such as Dr Thomas Arnold at Rugby and the Reverend Edward Thring at Uppingham,

who, according to Hunter Davies in Boots, Balls and Haircuts, saw

it as 'a way of installing order and discipline and also providing a healthy

activity for adolescent boys, distracting them from possibly more anti-social

or even disgusting personal activities. Many of these reforming headmasters

were clerics, muscular Christians who believed sport was good for the

soul, not just the body. The rules of their traditional school games were

formalised, inter-house competitions encouraged, with victors and champions

recognised and rewarded.' This period in English history also saw a fierce distinction between

the handling codes and the dribbling game. There were major differences

in values and approach between the proponents of each code, and endless

soul searching and debate about which was the worthier. The separation

into discrete and individual codes was messy and prolonged, but eventually

football evolved into three distinct streams - Rugby Union, Rugby League

and Association, the name of which gave rise to the shortened term of

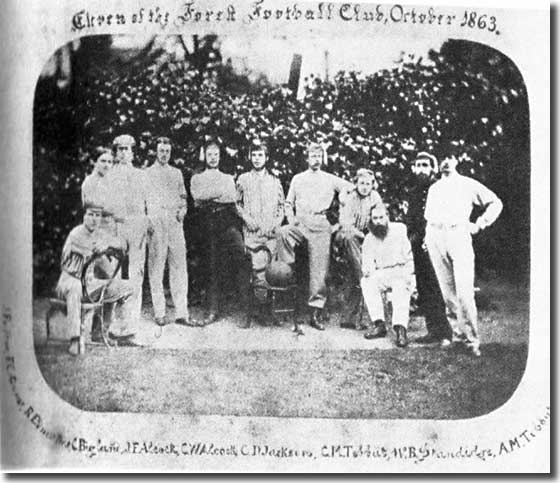

'Socker'. The real birth of football as an organised sport came on Monday, 26 October

1863, when a meeting was convened of representatives from a dozen of the

leading London and suburban football clubs of the day:

The meeting took place at the Freemasons' Tavern in Great Queen Street,

Lincoln's Inn Fields, London, and it was agreed that 'the clubs represented

at this meeting now form themselves into an association to be called The

Football Association.' However, it took another six meetings to formulate

the rules of football. The problem lay in co-ordinating the disparate codes of football played

around the country. There was a strong body of opinion in favour of banning

some of the practices allowed by the Rugby (School) code, already outlawed

by the Sheffield Rules of 1857 and the Cambridge Rules of 1862 and 1863.

But representatives of the Blackheath club, strong advocates of the Rugby

game, were unyielding. They insisted on the inclusion of two clauses in

the rules: first, that 'A player may be entitled to run with the ball

towards his adversaries' goal if he makes a fair catch' and, second, 'If

any player shall run with the ball towards his adversaries' goal, any

player on the opposite side shall be at liberty to charge, hold, trip

or hack him, or wrest the ball from him.' Finally, the dispute came to a head at a meeting held on 1 December,

the fifth such assembly of the new Football Association. A request by

the Blackheath group to adjourn the session was defeated by 13 votes to

4, and as a consequence they withdrew from the Association. The Laws of

the Game, evolved from the Cambridge Rules and now agreed by the FA, were

formally accepted, heralding the birth of Association Football. These first FA Laws were as follows: 1 - The maximum length of the ground shall be 200 yards, the maximum

breadth shall be 100 yards, the length and breadth shall be marked off

with flags; and the goal shall be defined by two upright posts, eight

yards apart, without any tape or bar across them. 2 - A toss for goals shall take place, and the game shall be commenced

by a place kick from the centre of the ground by 3 - After a goal is won, the losing side shall be entitled to kick off,

and the two sides shall change goals after each goal is won. 4 - A goal shall be won when the ball passes between the goal-posts or

over the space between the goal-posts (at whatever height), not being

thrown, knocked on, or carried. 5 - When the ball is in touch, the first player who touches it shall

throw it from the point on the boundary line where it left the ground

in a direction at right angles with the boundary line, and the ball shall

not be in play until it has touched the ground. 6 - When a player has kicked the ball, any one of the same side who is

nearer to the opponent's goal line is out of play and may not touch the

ball himself, nor in any way whatever prevent any other player from doing

so, until he is in play; but no player is out of play when the ball is

kicked off from behind the goal line. 7 - In case the ball goes behind the goal line, if a player on the side

to whom the goal belongs first touches the ball, one of his side shall

be entitled to a free kick from the goal line at the point opposite the

place where the ball shall be touched. If a player of the opposite side

first touches the ball, one of his side shall be entitled to a free kick

at the goal only from a point 15 yards outside the goal line, opposite

the place where the ball is touched, the opposing side standing within

their goal line until he has had his kick. 8 - If a player makes a fair catch, he shall be entitled to a free kick,

providing he claims it by making a mark with his heel at once; and in

order to take such a kick he may go back as far as he pleases, and no

player on the opposite side shall advance beyond his mark until he has

kicked. 9 - No player shall run with the ball. 10 - Neither tripping nor hacking shall be allowed, and no player shall

use his hands to hold or push his adversary. 11 - A player shall not be allowed to throw the ball or pass it to another

with his hands. 12 - No player shall be allowed to take the ball from the ground with

his hands under any pretext whatever while it is in play. 13 - No player shall be allowed to wear projecting nails, iron plates,

or gutta percha on the soles or heels of his boots. Despite the consensus view among the FA's members regarding these rules,

they were not universally accepted. For instance, both Glasgow's Queen's

Park, Scotland's first club, who were formed in 1867, and most of the

Sheffield clubs continued to operate with a number of variations. However,

both communities came into line with the FA in 1870, allowing matches

to be played to common rules between sides from all over the country. It was about the same time that positional play and team formations started

to assume importance. According to the Association of Football Statisticians:

'The new generation of footballers sought a scientific side to their endeavours

on the field. It was no longer sufficient merely to play football - one

had to play with purpose. A step to be taken in this direction was in

the deployment of forces, who should stand where, and who should do what. 'In the general run of football it had always been a case of every man

for himself, each doing 'Under the Association type of football, a favoured method was to employ

a full-back, a half-back, and eight forwards. Using this system, the full-back

was advised to 'brook no delay' in sending the ball into his opponents'

half of the field, the forwards to play in a close pack, a sort of scrummage,

backing up the man on the ball, and the half-back to kick or dribble at

his discretion. 'Queen's Park, in common with most of the Scottish association clubs,

deployed their men in the form of two full-backs, two half-backs, and

six forwards, the forwards themselves frequently operating in pairs, two

on the right wing, two on the left wing, and two in the centre. Notwithstanding

the demonstration of the excellence of this formation, the English clubs

preferred other means of placing ten men and a goalkeeper. The Scottish

style was suitable for the short-passing game, but it found little favour

south of the Tweed, and even less south of the Trent. The Englishmen were

wedded to the principle of individual play, the man on the ball endeavouring

to steer it by close dribbling through the ranks of his adversaries, while

his colleagues were supposed to stick right behind him to back him up,

as it was described, and to carry on the forward dribbling rush should

he be tackled; those few players not so engaged were expected, should

the ball come their way, to return it over the half way line with as little

delay as possible.' It was not until the late 1880's that the classic formation of two full-backs,

three half-backs and five forwards was popularly adopted, with the new

approach having less regard for the previously favoured dribble and headlong

rush through the middle. The emphasis now lay on usage of the wings, where

the defence was most sparse, to allow the cross into the centre and force

a panic in the penalty area. This change was prompted by alterations to the offside law in 1866. Previously,

any player who was in front of the ball when it was played was deemed

offside, effectively outlawing the forward pass. This rule was changed,

allowing advanced players to legally receive a pass providing there were

at least three opponents between themselves and the goal line. This reduced

the importance of dribbling and led to a preoccupation with a passing

game, both long and short, which was quickly mastered by Scottish clubs

and players, giving them a distinct advantage over their English counterparts. The Association of Football Statisticians: 'The superiority of the Scottish

'combination' game over the English style of individual dribbling and

backing-up was amply demonstrated when Queen's Park beat Notts County

by 6 goals to none at Hampden Park. When Englishmen had the ball they

were dangerous, though the Scottish pair of backs were well able to deal

with the menace. However, Notts had no answer to the speed and precision

of the short-passing game whenever Queen's Park had possession in that

match; they were running round in circles, never knowing where the ball

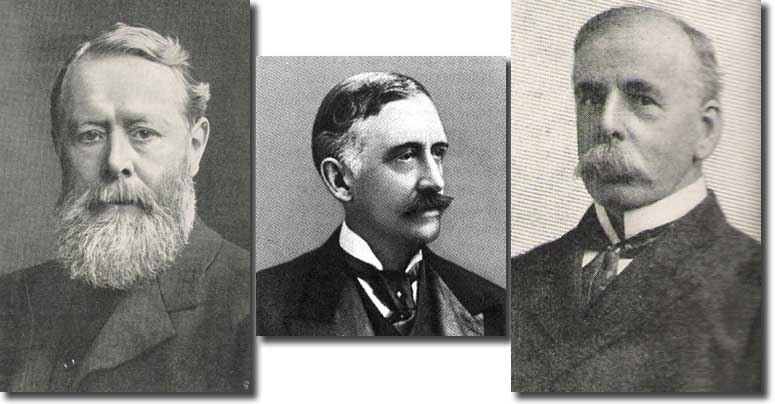

would pop up next.' The FA grew rapidly in importance following its formation and much of

its progress was due to the direction provided by a celebrated triumvirate

of leaders: Major (later Sir Francis) Marindin, RE, who became president

in 1874; Charles W Alcock, captain of the Wanderers FC, a leading side

from London who were composed of the best players to have graduated from

the public schools and universities, who became FA secretary in 1870;

and the Hon A F (later Lord) Kinnaird, captain of the Old Etonians FC,

who became FA treasurer in 1878. Geoffrey Green: 'Alcock, supported by the military discipline of Marindin

and the social graces of The major milestone in this jounrey came when the Football Association

finally recognised that there was a need for some form of organised competition.

Alcock the moving spirit in the inception of the Football Association

Challenge Cup competition. At a meeting held in the offices of The Sportsman in London on 20th July

1871, Alcock proposed 'that it is desirable that a Challenge Cup should

be established in connection with the Association, for which all clubs

belonging to the Association should be invited to compete'. The move received

support and was finally approved three months later, on 16 October. There were 15 entrants for that first competition, but none of them were

from Northern clubs, their fixture cards for the season having already

been agreed. There were only two non-Southern clubs (Scotland's Queen's

Park and Lincolnshire's Donington School). The other 13 clubs (Barnes,

Civil Service, Clapham Rovers, Crystal Palace, Hampstead Heathens, Harrow

Chequers, Hitchin, Maidenhead, Marlow, Reigate Priory, Royal Engineers,

Upton Park and Wanderers) were all from London and the Home Counties. Both Queen's Park and Donington were given byes in the first round, and

then Queen's Park had a walkover in the second when Donington scratched.

With five clubs left in the third round, Queen's Park received another

bye, so were in the semi finals without having played a match. They were

drawn against the Wanderers, and travelled to London from Glasgow with

the help of public subscription. After a hard-fought goalless draw, Queen's

Park, whose accurate passing style was a complete revelation in the South,

could not afford to stay in London for a replay and had to scratch. So

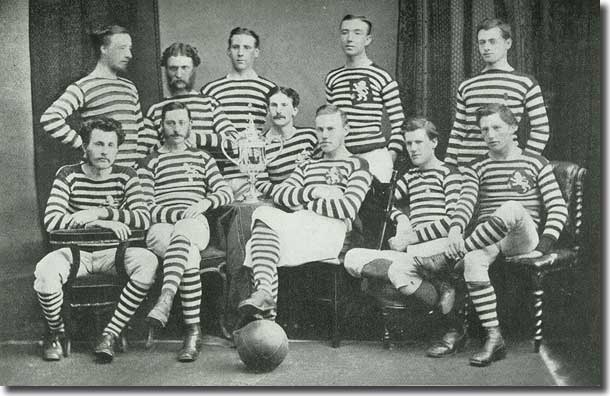

Wanderers were in the final. The Royal Engineers were favourites to win the final at odds of 7-4 on,

but the Wanderers secured a 1-0 victory to become the first holders of

the Cup in front of a crowd of 2,000 on 16 March 1872 at Kennington Oval.

It was fitting that Alcock should be the first captain to raise the trophy,

a silver cup scarcely 18 inches high. The following November saw the first ever international match, between

England and Scotland, held at the West of Scotland Cricket Ground, Partick.

The game finished in a 0-0 draw, which was something of a shock with the

number of attackers on the field. The formation of the Scottish FA was

still a year away, so the 'Scotland' side was organised by Queen's Park,

who provided six of the players. At this time, football was an avowedly amateur sport, played purely for

fun and exercise, with no commercial reward. The FA was founded by amateurs,

and all of the original entrants for the Cup were amateur. The 'amateur

era' was dominated by the In these early days, there was no thought of anyone being paid for their

participation. The very idea was anathema to the gentlemen players who

dominated the game and against all their ideals of sport and sportsmanship.

Things began to change with the coming of competition and the Cup, which

had its opponents who argued that the rivalry generated would lead to

the destruction of the true spirit of the game. In some respects they

were right. A direct outcome of the enthusiasm to win the 'little tin

idol' was the subversive growth of professionalism and the resulting transition

of power from the South to the North of England. Professionalism was finally

recognised in England in 1885. The Association of Football Statisticians: 'There was a feeling in Lancashire

that eventually some form of professionalism would have to be made legal.

In the end he Football Association would have to agree that some players

had to be paid. If it would not sanction the actual payment of wages,

then there would have to be a system whereby men were compensated for

time lost from work. 'The business was brought up at a meeting of the national body on 25

June, 1884. The Blackburn Rovers representative said that if players could

not be compensated for lost wages it would be the end of football for

working people in Lancashire. Major Marindin, from the Chair, said the

proposal was to alter the rules so that as well as actual out-of-pocket

expenses, loss of not more than one day's pay could be claimed. He said

the Committee did not like this "wages clause", but he realised

that its deletion would bear hardly on working men. Mr. Forrest (Lancashire),

said he would prefer that two days' loss of pay could be claimed, whereupon

Mr. Clegg argued, "if one, why not three, or even six?." There

ought not to be a wages clause at all. Mr. Pierce Dix, of Sheffield, bitterly

opposed the liberal attitude to loss of wages. They had gone over it before,

he said, and decided against it; now they seemed to be trying to upset

that verdict. Mr. Crump (Birmingham) said he did not consider football

should be limited to one class. He failed to see how a working man, receiving

a single day's pay for lost wages, could be termed a professional. 'The supporters of professional football argued lucidly and powerfully

and left the door open invitingly for negotiation. Their opponents, honest

men of principle though they were, could only fall back on honesty and

principle and the pessimistic cries that football was being ruined. But

for the most part, the true-blue amateurs of the South (and the Provinces),

listened with growing sympathy to the words of the Lancashire men. However,

they voted against the proposal.' Eventually the tide of professionalism swept over everything, leading

to an increase in the number of players, and the development of more competition. Philip Gibbons: 'Towards the end of the 1887/88 season, in early 1888,

Aston Villa's William McGregor, a committee member of Aston Villa and

a member of the Birmingham FA, sent a circular to five of the leading

professional clubs in England expressing his concern at what he saw as

a crisis in the Association game. 'McGregor, who had been a leading light in the Midlands when arguing

for the legalisation of professionalism, felt that football was in a poor

state, suggesting that a League system should be developed to keep the

competition going rather than the friendly games of little importance.

Fixtures were often cancelled on a Friday evening or Saturday morning

for no particular season, thus depriving thousands of spectators of their

Saturday afternoon sport, while the lack of income brought about by these

cancelled games forced clubs into bankruptcy, unable to pay players their

wages.' The circular, sent on 2 March 1888, read as follows: 'Every year it is

becoming more and more difficult for football clubs of any standing to

meet their friendly engagements and even arrange friendly matches. The

consequence is that at the last moment, through Cup-tie interference,

clubs are compelled to take on teams who will not attract the public. 'I beg to tender the following suggestion as a means of getting over

the difficulty in that ten or twelve of the most prominent clubs in England

combine to arrange home-and-away fixtures each season, the said fixtures

to be arranged at a friendly conference about the same time as the International

Conference. This combination might be known as the Association Football

Union, and could be managed by representative from each club. Of course,

this is in no way to interfere with the National Association; even the

suggested matches might be played under Cup-tie rules. However, this is

a detail. 'My object in writing to you at present is merely to draw your attention

to the subject, and to suggest a friendly conference to discuss the matter

more fully. I would take it as a favour if you would kindly think the

matter over, and make whatever suggestions you deem necessary. I am only

writing to the following - Blackburn Rovers, Bolton Wanderers, Preston

North End, West Bromwich Albion, and Aston Villa, and would like to hear

what other clubs you would suggest. 'PS - How would Friday, 23rd March, 1888, suit for the friendly conference

at Anderton's Hotel, London?' From such humble beginnings, the Football League competition was born. Philip Gibbons: 'As Mr McGregor took his place as president of the League,

it was decided to play the opening League games on 8 September 1888. However,

Mr McGregor was aware of the importance of not falling out with the Football

Association in London. He felt that, together, they would see the game

grow into a healthier state than it had been for a while. He believed

the League competition to be one of skill and consistency, while the FA

Cup would be won by the team playing the most spirited football over a

few games.' McGregor served as president of the League until he retired in 1894.

He was succeeded by Bolton Wanderers secretary-manager JJ (John) Bentley,

who held the role until 1910. Bentley's replacement was Liverpool's 'Honest'

John McKenna, who was elected to the League Management Committee in 1902,

became a vice president in 1908 and remained president until he died in

1936. In total contrast to the Cup when it started, the twelve founding members

of the Football League (Accrington, Aston Villa, Blackburn Rovers, Bolton

Wanderers, Burnley, Derby County, Everton, Notts County, Preston North

End, Stoke, West Bromwich Albion and Wolverhampton Wanderers) were equally

divided between Lancashire and the Midlands; most of them were professional

or at least semi-professional outfits. In 1892, a Second Division was

formed, and again it was made up almost entirely from clubs in the Northern

parts of the country. Only Grimsby and Lincoln City were not from the

North or the Midlands. Blackburn Rovers were the first Northern Cup finalists in 1882, but that

heralded the start of the Lancashire takeover. The plumbers and weavers

of Blackburn Olympic beat the gentlemen of the Old Etonians to take the

Cup up North in 1883, to be followed by their neighbours, Rovers, who

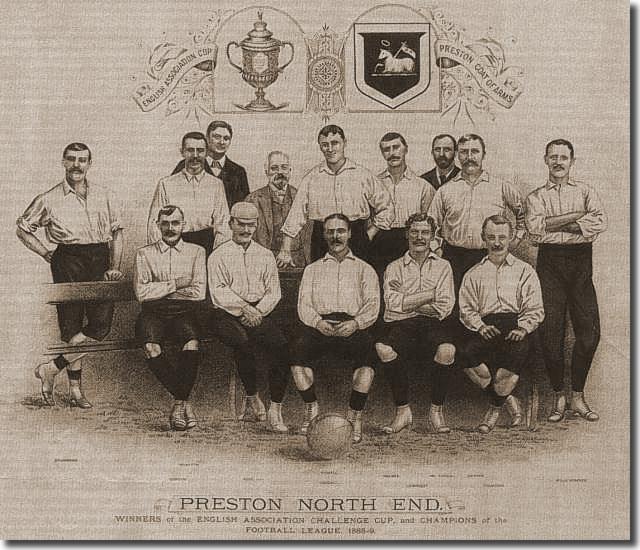

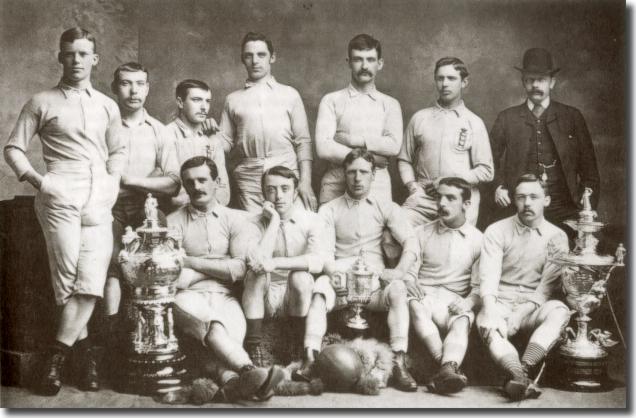

won in 1884, 1885 and 1886. When Preston won the first League and Cup

double Preston North End retained their League title in 1890, but their dominance

was wrested away by Aston Villa, the most successful English side of the

1890's and early 1900's; Villa were champions in 1894, 1896, 1897 (the

year they also won the Double), 1899 and 1900. They won the Cup in 1887,

1895, 1897 and 1905. Their Black Country neighbours, WBA and Wolves secured

the Cup in 1888, 1892 and 1893 and the beaten finalists came from these

same three clubs in 1886, 1889, 1895 and 1896. The only other side which really got a regular look in were Sunderland,

the 'Team of All the Talents'. Packed with Scottish footballers, they

were champions in 1892,1893, 1895 and 1902. Their North East neighbours

Newcastle United were champions in 1905 and lost the FA Cup Final to Villa

that same year. During this period, the new heroes of the game were substantially different

from their forebears, as Hunter Davies records: 'The first football heroes were the amateurs, like Kinnaird and Alcock

and G O Smith of Oxford and the Corinthians, their names becoming known

to all football fans of the time. Vivian Woodward of Spurs, one of the

last amateur stars to play in a professional team, became famous when

he scored six goals for England against Holland in 1909. But it was the

professional players who quickly became household names, in football households,

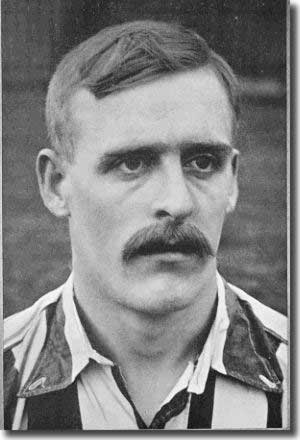

such as John Goodall, inside forward for the Preston North End "Invincibles"

team of 1889. Forwards, like Billy Bassett, tended to become the stars,

as they do today, attracting all the headlines, acclaimed as "Wizards

of Dribble". Steve Bloomer of Derby was famous as a prolific goalscorer,

scoring 353 League goals between 1892 and 1914. As early as 1892, one

commentator, C Edwards, was writing that star players were becoming "better

known than the local member of Parliament".' Spartacus Educational: 'In the 1896/97 season Sheffield United were runners

up behind the double-winning Aston Villa ... In the home game against

the champions, Foulke caused a stir by bouncing the ball as far as the

halfway line. This was within the rules at the time, but as players were

able to barge into other players when they had the ball, goalkeepers saw

that tactic as very risky. However, Foulke was fairly confident that he

would be able to regain possession of the ball. C B Fry, the famous cricketer,

who also played football for Southampton, remarked: 'Foulke is no small

part of a mountain. You cannot bundle him.' 'Foulke won his first international cap against Wales on 29 March 1897.

Although England won 4-0, surprisingly, it was the only time he played

for his country ... As the Sheffield Daily Telegraph pointed out:

"It is a pity that Foulke cannot curb the habit of pulling down the

crossbar, which on Saturday ended in his breaking it in two. On form,

he is well in the running for international honours, but the Selection

Committee are sure to prefer a man who plays the game to one who unnecessarily

violates the spirit of the rules." 'In 1895 Foulke only weighed 12st 10lb but over the next few years he

put on a lot of weight and was nicknamed "Fatty" or "Colossus"

by the fans. He once said: '="I don't mind what they call me as long

as they don't call me late for my lunch." ... Foulke was 6ft 2ins

tall. At the time the average height for an adult male was only 5 ft 5

ins and therefore he towered over most of the players. This can be seen

in the team photographs taken at the time. 'In a game against Liverpool in November, 1898, George Allan tried to

intimidate Foulke. The Liverpool Post reported that 'Allan charged

Foulke in the goalmouth, and the big man, losing his temper, seized him

by the leg and turned him upside down.' As the Athletic News pointed

out, when this happened: "He doesn't claim a foul, but simply places

that paw of his on the shoulder of the charging gentleman in a most fatherly

manner, and pushed him aside with an expression of get on one side, little

boy." 'On another occasion he fell on Laurie Bell of Sheffield Wednesday. As

he later recalled: "It was really all an accident. Just as I was

reaching for a high ball Bell came at me, and the result of the collision

was that we both tumbled down, but it was his bad luck to be 'Foulke was also a talented cricketer and played for Blackwell Colliery

in the Derbyshire League. One journalist joked that every time Foulke

went into bat "there is an appeal against the light." 'Foulke's main sport was football and he was also a member of the Sheffield

United team that played Southampton in the 1902 FA Cup Final. Sheffield

took an early lead but Southampton scored a controversial equalizer and

the game was drawn 1-1 ... Foulke was furious that the equalizing goal

had been given after the game he went searching for the referee. The linesman,

J T Howcroft, described how Frederick Wall, secretary of the Football

Association, tried to placate the goalkeeper: "Foulke was exasperated

by the goal and claimed it was in his birthday suit outside the dressing

room, and I saw F J Wall, secretary of the FA, pleading with him to rejoin

his colleagues. But Bill was out for blood, and I shouted to Mr. Kirkham

to lock his cubicle door. He didn't need telling twice. But what a sight!

The thing I'll never forget is Foulke, so tremendous in size, striding

along the corridor, without a stitch of clothing." 'After playing in over 350 games for Sheffield United Foulke decided

to leave the club when he refused to take a pay cut. In May 1905 Foulke

was sold to Chelsea for a transfer fee of £50 ... Chelsea had just joined

the Football League and in his first season he helped them to finish in

3rd place in the Second Division ... However, he continued to put on weight.

According to one report, Foulke was known to arrive early for breakfast,

set for the entire Chelsea team, and eat the lot. 'Foulke only played 35 games for Chelsea before moving to Bradford City

... The Bradford Daily Argus reported that 'there is no doubt that the

mighty goalkeeper is doing a great deal in the direction of inspiring

confidence in the team.' This did not stop the newspaper making fun of

their large goalkeeper. On 29th September, 1906, it reported that a cab

horse had a narrow escape when it nearly collided with Foulke when he

was crossing the Strand. Foulke was quoted as saying: "I would have

jumped on the beggar's back before I would have let him come into me." 'William Fatty Foulke died on 1st May 1916. The death certificate gives

"cirrhosis" as a major cause of death. There is no truth in

the claim that Foulke ended his life in poverty working at a sideshow

on Blackpool beach.' Fatty Foulke was a legend in his time, but probably the best remembered

from that pre-First World War period, in the sense that he still appears

in all the record books, is Alf Common. What a sensation he created in

February 1905 when he was transferred from Sunderland to Middlesbrough

for the then astronomical sum of £1,000, the first ever four-figure transfer

fee. The FA and the League, having imposed a maximum wage, had contemplated

a maximum transfer fee, and in 1899 the FA suggested the limit should

be £10, but they felt unable to impose it, so over the next few years

it slowly crept up to around £400 for the best players. A sudden jump

to £1,000 amazed everyone. An investigation was set up to find out if

anything unlawful had been done. The transfer was all above board, but

when they went through the Boro books, it was revealed they'd paid illegal

Cup bonuses to players in the previous season. Football purists were aghast, saying it was the end of football as they

had known it. Money was ruining the game, players had become mercenaries

with no loyalties, a new form of white slave trade had now been introduced,

where will it end - will we soon have £2,000 transfers or even, perish

the thought, will there one of these days be a £10,000 transfer fee? Part of the surprise was the fact that it was Middlesbrough, a relatively

new club, only six years old. But Boro that season were desperate, struggling

near the bottom of the First Division and badly in need of a goalscorer.

Some things never change. They had tried for one, who turned them down,

and so decided to lash out on Sunderland's bustling, 5ft-8ins-high, 13-stone

Alf Common. Sunderland had bought him from Sheffield United just a year previously

for £350, so naturally Sheffield United were pretty livid that Sunderland

had made such a huge profit in a short time. Charles Clegg, chairman of

the FA, who was also a Sheffield As so often happens in football, with almost predictable irony, Common's

first game for Boro, on February 25, 1905, was away to Sheffield United.

They won 1-0, with Common scoring from a penalty. It was Boro's first

away win for nearly two years and they stayed up, with Common taking over

as captain. So, this first ever shock-horror mega transfer deal was considered

money well spent. Common was a jovial, ruddy-faced, rather tubby player, famous for his

attempts to lose weight.ounds like another well-known North-Easterner,

P Gascoigne. At the age of 30, Common was transferred to Woolwich Arsenal

who devised all sorts of physical exercises and strenuous walks to get

him slim, without much success. When he retired he became a publican,

running the Alma Hotel at Cockerton for 11 years. 'A footballer behind

the bar is as great an attraction as a long-legged giant or a fat woman,'

reported the Athletic Journal as early as 1890. The tradition of players becoming publicans lived on for almost the next

100 years, at least for those who had managed to save a few pounds. Even

as late as 1974, it was what Sir Alex Ferguson first did when his career

with Rangers and Ayr United was coming to an end. At the time, he wasn't

quite sure what to do with the rest of his life. Alf Common was known as a practical joker, but alas none of his wheezes

have survived. Footballers have always been known for their amusing as

well as riotous behaviour. A writer in the Book of Football in 1905 described one of the

tricks which the Newcastle United players got up to while travelling by

train. They had a special saloon provided by the North Eastern Railway

Company, divided into two compartments by a sliding door, where the players

passed the time playing whist. If a bossy ticket collector interrupted

their games by laboriously checking the tickets and counting all the players,

they deliberately set out to confuse him. When the ticket inspector announced

that there were 22 players, yet only 16 tickets, he naturally suspected

some fiddle was going on, and he proceeded to call for the station master.

Only later did he discover that some players had been sliding between

the two doors and had been counted twice. What japes! to assume something resembling today's shape, when it became refined and

organised, helped by the advent of a common set of rules and standards.

The Victorian era brought with it many advances, pioneering thinkers and

an urge to bring order in all things.

to assume something resembling today's shape, when it became refined and

organised, helped by the advent of a common set of rules and standards.

The Victorian era brought with it many advances, pioneering thinkers and

an urge to bring order in all things.

the

side losing the toss for goals; the other side shall not approach within

10 yards of the ball until it is kicked off.

the

side losing the toss for goals; the other side shall not approach within

10 yards of the ball until it is kicked off. as

he thought best. The new thinking perceived that the best way to the opponents'

line, and the best way of keeping an adversary away from its own end,

could be greatly assisted by the intelligent marshalling of human resources.

as

he thought best. The new thinking perceived that the best way to the opponents'

line, and the best way of keeping an adversary away from its own end,

could be greatly assisted by the intelligent marshalling of human resources. Kinnaird, was the real driving force and genius in his position as secretary,

a rank that in due course was to grow to one of vast importance in the

years of expansion ahead. Alcock was a lover of true sport and sportsmanship.

For a quarter of a century he held the reins of administration while the

character and significance of football underwent a crucial change. The

part he played in all this evolution was beyond measure. That must be

repeated, for it was his idea of the Cup and international football that

finally set the game on its pedestal. He was the one who set a light to

what was one day to become a worldwide fire.'

Kinnaird, was the real driving force and genius in his position as secretary,

a rank that in due course was to grow to one of vast importance in the

years of expansion ahead. Alcock was a lover of true sport and sportsmanship.

For a quarter of a century he held the reins of administration while the

character and significance of football underwent a crucial change. The

part he played in all this evolution was beyond measure. That must be

repeated, for it was his idea of the Cup and international football that

finally set the game on its pedestal. He was the one who set a light to

what was one day to become a worldwide fire.' Wanderers

and the Royal Engineers, and other similarly Corinthian outfits like Oxford

University and the Old Etonians.

Wanderers

and the Royal Engineers, and other similarly Corinthian outfits like Oxford

University and the Old Etonians.

underneath,

and I could not prevent myself from falling with both knees in his back.

When I saw his face I got about the worst shock I ever have had on the

football field. He looked as if he was dead."

underneath,

and I could not prevent myself from falling with both knees in his back.

When I saw his face I got about the worst shock I ever have had on the

football field. He looked as if he was dead." United man, was particularly upset.

United man, was particularly upset.