|

|

|

History

of the Club - The Seventies

1969-79

As the 1960's drew to a close, there was little dispute as to which was

England's premier club side: Leeds United had won the League championship

in April 1969 with a record points total, suffering just two defeats and

conceding 26 goals. For United manager Don Revie, the title was the culmination

Revie refused to rest on his laurels after the title triumph. He broke

the British transfer record when he paid £165,000 to relegated Leicester

City for the signature of England Under-23 goal poacher Allan Clarke.

In earlier years, the board had hesitated when Revie asked them to break

the transfer record to sign Alan Ball; by 1969, none of the directors

were prepared to deny Revie even his most unreasonable request. Over the previous decade, United had generally found goals hard to come

by and Revie reasoned that if he seriously hoped to win the European Cup,

Leeds would need a cutting edge. Clarke was renowned for his clinical

efficiency in front of goal and seemed to be the man to solve the problem,

though he was reputed to be something of a disruptive influence in the

dressing room. Clarke's arrival led to Mike O'Grady leaving for Wolves

after the winger lost his place to a rejuvenated Peter Lorimer. The early signs were promising: United won the curtain-raising clash

for the FA Charity Shield by beating Cup winners Manchester City 2-1 and

then broke a club record when they netted ten against Norwegian part timers

Lyn Oslo on their European Cup debut. Clarke scored twice, but centre-forward

Mick Jones stole the show with a hat trick. Leeds were certainly a stronger attacking force now, scoring ten in two

League matches against Nottingham Forest and winning 3-0 in both legs

of their European Cup pairing with the powerful Hungarians, Ferencvaros. United spent most of the season locked in a two way tussle with Everton

for the League championship, and a 5-2 victory at Stamford Bridge in January

1970 against Chelsea, also in the running, signalled the strength of their

challenge. They took that form into the FA Cup, where fortune favoured

them with draws against lowly opposition in Swansea, Sutton, Mansfield

and Swindon. By the beginning of March, Leeds looked set fair for the unprecedented

treble of League, Cup and European Cup. It was their very consistency,

ironically, that was their greatest threat. The season was drastically

foreshortened by the decision to give Sir Alf Ramsey's England team a

lengthy period to acclimatise to the alien conditions they would face

in Mexico as they defended their World Cup trophy. When compounded by

United's progress on three fronts, this meant appalling fixture congestion

for Revie's charges. The three match marathon required to see off Manchester United in the

FA Cup semi final was the straw that broke the camel's back. In the fourteen

days between 21 March and 4 April, Leeds had to play eight times. Don

Revie decided enough was enough and surrendered the chase for the title.

He began relying almost entirely on his reserve pool for League games,

a decision that brought a £5,000 fine from the Football League. When Revie

did deign to play first teamers his reward was to see England full-back

Paul Reaney suffer a broken leg against West Ham. The injury kept Reaney

out of the remaining weeks of the season as well as England's World Cup

campaign. Revie's gamble of concentrating on the knockout trophies backfired. With

his men dropping through physical and mental exhaustion, they underperformed

badly and lost both legs of the European Cup semi final against Celtic,

despite a memorable goal at Hampden from Billy Bremner. United recovered sufficiently to hammer Chelsea on a pudding of a Wembley

pitch in the FA Cup final. Eddie Gray tortured his marker, David Webb,

but Leeds couldn't score the goals their play deserved and were undone

by a late equaliser from Ian Hutchinson. In the Old Trafford replay, their dominance was not quite so absolute,

but they had still shown enough to merit victory before Chelsea fought

back to first equalise and then snatch a dramatic winner through Webb

in a heartbreaking finale to a remarkable season. Captain Billy Bremner was voted Footballer of the Year, while Revie was

awarded both an OBE and the Manager of the Year trophy, but these were

scant recompense for such major disappointments. Seemingly none the worse for a series of events that would have unhinged

most clubs, Leeds were quickly back to peak form at the start of the 1970/71

campaign, once again setting the pace in the chase for the League title. They stormed away from the very first game, leaving the pack trailing

in their wake. A dogged Arsenal team eventually emerged as the only serious

challengers as they shamelessly aped United's historic trademarks of defensive

resilience and narrow victories. They chased them remorselessly throughout

the autumn months and pressed their pursuit ever more tenaciously in the

spring, launching an indomitable assault on a gap that had once seemed

unbridgeable. Revie was deprived of both Bremner and Gray for most of the spring and

United's self assurance was badly shaken by a shock 3-2 defeat at Fourth

Division Colchester United in the FA Cup fifth round in February. Two

months later, perverse refereeing from Ray Tinkler provoked a riot at

Elland Road when West Bromwich Albion inched out a controversial 2-1 victory. Revie was beside himself with anger at Tinkler's display, accusing him

bitterly of ruining nine months' hard work. The More problematic, however, were the way the two matches undermined their

challenge, though United responded stoically by winning their remaining

three league games without conceding a goal. It was not enough, however. Arsenal were consistency personified in the closing weeks; even when

Leeds beat the Gunners with a controversial goal by Jack Charlton at Elland

Road at the end of April, it could not halt the Londoners' push for the

title. Despite amassing 64 points, United had to be content with another

runners up spot after Arsenal won their final game at Tottenham with a

goal from Ray Kennedy. They rubbed further salt in the wound by doing

what Leeds had often promised but always failed to do, becoming only the

second club in the Twentieth Century to complete the League and Cup double. United had at least some recompense when they won the Fairs Cup for the

second time. They beat Liverpool in a two legged semi final thanks to

a comeback goal by Bremner in the first leg at Anfield and beat Italian

giants Juventus on the away goals ruling after both legs of the final

ended even. It was something of a hollow feeling after coming so close

to regaining the League title, but after a couple of years without a trophy

they at least had something to mark their efforts. The crowd's behaviour during the defeat to West Bromwich Albion led to

disciplinary action from the Football League; Elland Road was closed for

a month and United had to stage the first four 'home' League fixtures

of 1971/72 in the stadiums of various other Yorkshire clubs. They only

dropped two points in those matches, but in a tight race for the league

title, the shortfall proved costly indeed. When United were eventually allowed to resume action at Elland Road,

they found outstanding form, dropping just two further points all season.

On their travels, they were considerably less impressive and by early

October they had been beaten four times. It was their poorest start for

years and for once European competition provided minimal distraction.

After winning 2-0 in Belgium against Lierse in the first leg of a UEFA

Cup-tie, Revie, considering the outcome a formality, chose to draft in

a number of reserves for the home match. The Belgians thrashed United

4-0. Revie's thoughts had turned to rebuilding his team; in early 1970 he

had offered Sutton centre-half John Faulkner the opportunity to become

a long term replacement for the ageing Jack Charlton and later signed

young Morton striker Joe Jordan for a pittance. Now, he agreed a record

£177,000 fee with West Brom for their 21-year-old Scottish midfielder

Asa Hartford. But the move was scuppered when the medical examination

identified a heart problem. Hartford went on to make a fine career for

himself with Manchester City and Everton and featured in two World Cup

finals with Scotland. United were not deterred by the setback and their football reached new

heights in the spring of 1972. The 5-1 hammering of Manchester United

and a breathtaking 7-0 slaughter of Southampton were televised on Match

of the Day, allowing a nationwide audience to lap up the breathtaking

football United were now dishing up. The style and cocksure manner of

their displays, particularly in the drubbing of the Saints, and their

introduction of gimmicky numbered stocking tags quickly led to them being

branded 'Super Leeds'. The later stages of the Southampton game saw them

imperiously playing keep ball with showy flicks and tricks, rubbing in

their superiority. It was memorable stuff as United swept all before them,

pushing forward confidently to what seemed an inevitable League and Cup

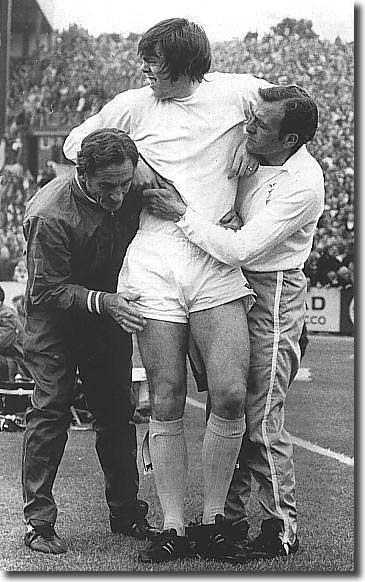

double. However, they were forced to face the run in without England left-back

Terry Cooper, who suffered a broken leg against Stoke City. He was out

of action for two years and was never the same player again, though he

was given a sentimental recall to the England team in 1974. The versatile

Paul Madeley smoothly plugged the gap in defence. A 3-0 defeat of Second Division Birmingham City in the FA Cup semi-final

at Hillsborough earned United a Wembley date with Arsenal in the Centenary

final, a match attended by the Queen. The Whites were thirsting for revenge

after losing out to Gunners in the League a year previously and marked

the occasion by winning the trophy for the first time after Allan Clarke

headed home the only goal. David Harvey played in both semi final and

final having secured the spot as first choice keeper after Revie finally

lost patience with the inconsistency of Gary Sprake. Revie's men had little opportunity to bask in the glory of their victory;

the League perversely refused United's request that their final League

game should be postponed to allow the players to recover. They travelled

straight from Wembley to Wolverhampton for a match against Wolves on the

Monday night, requiring a draw to win the title. An inspired Wanderers team won 2-1 after a thunderous and emotion-soaked

clash, leaving Brian Clough's Derby County, who had already completed

their programme and were sunning themselves on a beach somewhere, to claim

the championship. Leeds were consigned to the runners up spot for the

third successive season. Revie was distraught, complaining of the Wolves defeat, "It's just too

much. We should have had three clear penalties. But I was proud of the

team. I don't know where they got the energy from in the second half." During the summer of 1972, Revie continued to rebuild. Veteran centre-half

Jack Charlton was now 37 and close to retirement while Terry Cooper's

broken leg would keep him on the sidelines for almost two years, so United

badly needed some defensive reinforcements. Revie's solution lay close

to home as he signed Huddersfield Town defenders Roy Ellam and Trevor

Cherry. Cherry enjoyed a long and successful career at Elland Road, but Ellam

never made the grade, looking completely out of his depth. Revie quickly

admitted his mistake and turned to another option, Gordon McQueen, a raw

20-year-old, who had been signed from St Mirren for £30,000. Paul Madeley

and Charlton shared the No 5 shirt between them for the majority of the

1972/73 campaign. Eddie Gray's 18-year-old brother Frank was given his debut, though it

would be another two years before he was ready to claim a regular The season began badly - United lost 4-0 at Chelsea on the opening day.

Norman Hunter was missing through suspension and Cherry and Ellam struggled

to forge any sort of understanding with their new colleagues. Mick Jones

went off injured in the first half and when David Harvey was also forced

to withdraw with concussion, Leeds were left to battle for more than an

hour with ten men, as Peter Lorimer took up the goalkeeper's gloves; he

never had a prayer. The defeat set the tone for a disappointing campaign. Despite being in

contention for the title for most of the season, United struggled to demonstrate

that they were actually capable of winning the championship, eventually

trailing in third behind Liverpool and Arsenal. A season that began miserably also ended depressingly. Leeds were the

hottest favourites in years when they reached the FA Cup final. They were

pitted against Second Division Sunderland, managed by Bob Stokoe, a bitter

critic of Don Revie. Stokoe had accused Revie of trying to bribe him in

the early 60s when he was a Bury player and had borne a grudge against

him ever since. United suffered one of the greatest shocks in the competition's history

- they were undone by a first half goal from Ian Porterfield and a miraculous

double save by keeper Jim Montgomery. Stokoe revelled in the victory,

dancing gleefully across the turf at the end to hug Montgomery as the

United party looked on in despair. Leeds had also qualified for the Cup Winners Cup final, but went into

the game missing key men through suspension and injury. Bremner, Clarke,

Giles and Eddie Gray were all unavailable, while the team were unsettled

by the news that Don Revie had agreed to take the manager's job at Everton. The match, in Salonika against AC Milan, was hugely controversial. Paul

Madeley was unlucky to be penalised for a soft challenge after five minutes

and Chiarugi's long range free kick somehow crept past David Harvey into

the net. United were denied a number of penalty claims and Norman Hunter

was dismissed for retaliation after being the victim of a series of niggling

fouls. Referee Christos Michas was rumoured to have been bribed by the

Italians and he certainly seemed to favour Milan, facing a chorus of boos

from his Greek countrymen at the end of the game. He was later banned

for life by UEFA. There was widespread talk during the summer that United were no longer

the force they once had been. The Sunderland defeat had scarred them badly

and critics pointed to signs of wear and tear. The young men of Revie's

early years had aged together and there were a number of claims that they

were over the hill. Elder statesman Jack Charlton, now 38, was one for whom time was up and

he called it a day. He retired to take over as manager of Middlesbrough,

whom he led to the Second Division championship at the first time of asking.

At the beginning of October, another old stager, Welsh international Gary

Sprake, moved on to Birmingham City in a six figure deal, a record for

a keeper. He was replaced by the little known David Stewart of Ayr United. Don Revie rejected Everton's overtures in the end and chose to remain

at Elland Road, his pride salved by an offer of improved terms from the

board. He had also turned down an offer from the Greek FA, determined

that his club would finally secure the second title they had missed out

on so often. He somehow managed to inspire his troops to a remarkable

swansong. Eddie Gray and Johnny Giles missed most of the campaign through injury,

though Gordon McQueen, Terry Yorath, Joe Jordan and Trevor Cherry proved

more than adequate reinforcements, providing great support for the usual

suspects. Bremner, Jones, Clarke, Lorimer, Madeley and Hunter were in

imperious form as United swept all before them, earning unanimous acclaim

from the critics. Leeds went off in unstoppable fashion, winning seven games on the bounce.

They extended their unbeaten League run to 29 games, playing superlative

football. In the end, the psychological burden of months of front running

started to eat away at them, and draws were soon all too regularly punctuating

the results. FA Cup defeat in February against Second Division Bristol City hinted

that United might be human after all, but Revie maintained that the exit

would allow them to concentrate on securing the title, without the distraction

of hunting multiple trophies. In their 30th League game, on 23 February, Leeds took a 2-0 lead at Stoke

City and seemed likely to continue their unbeaten run, but the Potters

fought back with real verve to win 3-2. That brought back all the old

anxieties and paranoias; three further defeats in a poor spell of form

had Revie beside himself as Liverpool reeled in Leeds' lead with dogged

determination. However, United managed to rally at the death; when old rivals Arsenal

sprang a shock on 24 April by winning at Anfield it secured a second League

title for Leeds without their even playing. They could enjoy their ultimate

game, in London against Queens Park Rangers, under no pressure. Allan

Clarke scored the only goal of the game to see United home in some style.

They had wavered badly as the pressure got to them but in the end they

were the worthiest of champions. At their best in 1973/74, Leeds were

almost unplayable. That triumph was a marvellous parting shot for Revie. During the summer

he was appointed England team manager, taking trainer Les Cocker with

him. Joe Mercer had taken over as caretaker manager following the FA's

dismissal of Sir Alf Ramsey, but, after making clear his interest in the

position, Revie was a shoo in when the time came for a Revie's replacement at Elland Road was a controversial one; the manager

himself had nominated Johnny Giles as his successor, but the board, perhaps

fearing that Billy Bremner would see such a move as a personal snub, instead

appointed former Derby County manager Brian Clough as the new man. The appointment came as a major shock; Clough had long been a fierce

critic of Revie and United, accusing them of cheating and gamesmanship.

He seemed the unlikeliest of choices. Clough did little to endear himself to the United players, telling them

to throw their medals in the bin because they had obtained them dishonestly.

Following an ill-tempered Charity Shield match against Liverpool, which

saw Billy Bremner and Kevin Keegan sent off for fighting and United losing

on penalties, there was a poor start to the title defence with a single

victory from the first six games. When invited to do so by the directors, the players made their feelings

about Clough plain, and there was no going back. After just 44 days in

the job, Clough was shown the Elland Road door. He departed Yorkshire

with a substantial pay off and a binding promise that the club would pay

his income tax for the following three years; the board were left with

egg on their faces and a substantial hole in their wallets. Two of the players that Clough bought for Leeds, John O'Hare and John

McGovern, followed him to glory with Nottingham Forest. Clough's other

signing, Duncan McKenzie, who had joined for a club record £240,000 fee

from Forest, remained and became a cult figure at Elland Road with his

skills, trickery and poaching instincts. McKenzie had some other bizarre

talents: he could hurl a golf ball the length of the Elland Road pitch

and vault over a Mini. Bolton boss and former Blackpool and England captain Jimmy Armfield was

the board's choice to steady the United ship. They were too far off the

pace in the League to make a serious challenge and trailed in ninth, but

Armfield steered the team to the European Cup final. They overcame a strong

Barcelona side, Johann Cruyff and all, in the semi final. There was a

memorable draw in the second leg at the Nou Camp after United were reduced

to ten men when Gordon McQueen was sent off. Leeds enjoyed little luck in the Paris final against Bayern Munich, having

a Peter Lorimer 'goal' disallowed and being denied a clear penalty when

Franz Beckenbauer hacked down Allan Clarke. The Germans scored two late

goals, provoking frenzied reactions and a bout of missile throwing from

disgruntled United fans. UEFA took a dim view of the incidents and banned the club from European

competition for four years, something of an empty sanction as they had

failed to qualify for Europe for the first time in a decade. Jimmy Armfield later managed to get the ban reduced to two seasons, but

the evening symbolically closed the curtain on a remarkable period in

the club's history. Things would never be the same again. Long serving chief coach Syd Owen left Elland Road to assist former United

player Willie Bell, now manager at Birmingham. His replacement was former

Arsenal coach and England defender Don Howe as Armfield started rebuilding

in earnest: Terry Cooper left to join Middlesbrough, now managed by Jack

Charlton, while Johnny Giles became player manager at West Bromwich Albion. Of Revie's other stalwarts, Gary Sprake and Charlton had departed the

club in 1973; Mick Jones finally admitted defeat in October 1975 and announced

his retirement after years suffering with knee injuries; Mick Bates moved

on to Walsall in June 1976 after tiring of being the perennial reserve.

Billy Bremner, Norman Hunter and Terry Yorath left a few months after

Bates, while Paul Reaney, Allan Clarke, Joe Jordan and Gordon McQueen

stuck around until 1978. In the summer of 1979, Peter Lorimer and Frank

Gray both moved on, but brother Eddie, David Harvey and Paul Madeley were

still first team regulars at the end of the decade. In 1975/76 Terry Yorath assumed the No 10 shirt vacated by Giles, though

he had none of the Irishman's style and passing ability, relying instead

on guts, determination and spirit. He was always likely to suffer by comparison

and the unforgiving fans never fully warmed to him. Duncan McKenzie was a regular goalscorer throughout the campaign, partnering

Allan Clarke for the most part as Joe Jordan sat out the first half of

the campaign with injury. McKenzie top scored with sixteen goals in 39

League appearances, adding another in 4 Cup games. Leeds enjoyed a decent run of results through the autumn, opening with

five wins out of the first seven games and then from mid-November to mid-January

they won eight games out of nine. It was a false dawn and the positive

spell gave way to a succession of defeats. A run of one win in ten between

January and March knocked the stuffing out of the team. They did stage

a brief revival, hinting at a late surge, before securing just three points

out of the final ten to destroy any title aspirations. Nevertheless, they

did enough to finish fifth, nine points behind champions Liverpool. The domestic cup competitions brought only embarrassment as United suffered

defeats to inferior opposition. Second Division Notts County beat United

1-0 at Meadow Lane in the League Cup, while Crystal Palace of Division

Three won by the same score at Elland Road in the FA Cup. During the summer of 1976, Jimmy Armfield confided in McKenzie that he

planned to rebuild the team around him and Trevor Cherry. Unimpressed

by the promise, McKenzie departed for Anderlecht, dismaying supporters

who had loved his colourful flair. Terry Yorath, unsettled by barracking

from the fans, departed for Coventry and old stagers Billy Bremner and

Norman Hunter both moved on early in the new season, ending lengthy associations

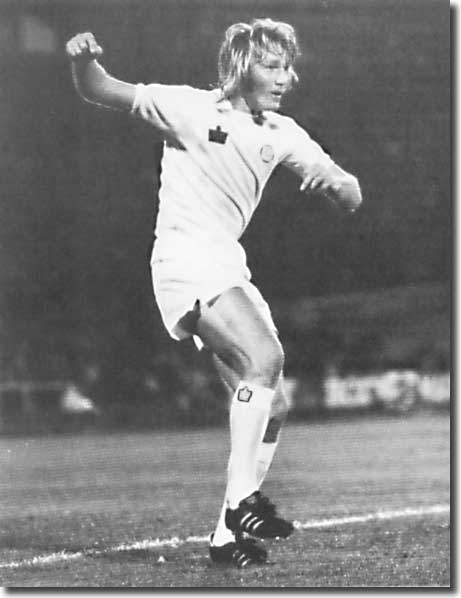

with the club. It felt unmistakably like the end of an era. As a replacement for McKenzie, Armfield recruited one of the game's other

great entertainers, paying Sheffield United £240,000 for England schemer

Tony Currie. He also brought in young Burnley striker Ray Hankin in a

£170,000 deal. The manager was forced to give first team baptisms of fire

to youngsters like Peter Hampton, David McNiven, Byron Stevenson, Carl

Harris and The side's League form was patchy and they could only summon up fifteen

League victories all season. Their start was poor with one success in

the first nine matches. They rallied a little through the autumn but continually

struggled for goals. The Yorkshiremen faded away to finish tenth, their

lowest placing in thirteen years. On a more positive note, there was an exciting FA Cup run as United beat

Norwich (5-2 with a rare goal from Paul Reaney), Birmingham, Manchester

City and Wolves to reach the semi finals, where they were drawn with Manchester

United. They conceded two early goals in the Hillsborough semi and even

after Allan Clarke pulled one goal back, they couldn't recover. There was a desolate feeling about the club as an empty season drew to

a close. The crowd of 16,891 who watched the Elland Road draw with West

Ham on 26 April was the lowest since the club's return to the First Division,

bearing testimony to the depression felt by the United supporters. Undeterred by such dismal events, Armfield signed Aberdeen winger Arthur

Graham for a £125,000 fee and later paid £175,000 for Burnley's diminutive

midfielder Brian Flynn. Flynn formed a good midfield partnership with

Tony Currie, who enjoyed an outstanding 1977/78 season. Andrew Mourant described Currie as "a pivotal figure, the like of which

had never been accommodated in any Revie team. Much, sometimes too much,

depended on Currie's mood. He was an abundantly gifted midfielder; few

sights at Elland Road have been more enthralling than that of Currie cantering

about the pitch, spraying passes in all directions and indulging in his

speciality of spectacular long range goals. But sometimes he appeared

maddeningly languid; the authoritarian gang of three, Bremner, Giles and

Hunter, who might have chivvied him along, had gone. A hard-running game

was not Currie's favoured style and when he was disinclined to play, Leeds

looked pedestrian." With Graham, Currie and Flynn providing the ammunition, Armfield deployed

Joe Jordan and Ray Hankin as a ferocious twin battering ram up front as

Allan Clarke struggled for fitness. The side began the campaign well and at the turn of the year they were

looking on the verge of a push for the title, but then faded badly. Jordan had long been unsettled at Elland Road following the club's refusal

to sanction a transfer in 1975. "Leeds had an offer for me from Bayern

Munich after the European Cup final and I wanted to go. After that team

was broken up, I thought that was it. I wanted to play in Europe ... nothing

against Leeds. But they wouldn't let me and I was annoyed at that. I was

a bit disillusioned, as a lot of people were. I wanted to try and win

things and I really didn't think we were going to do that." Jordan demanded

a transfer and was sold to Manchester United for £300,000 in January. The following day, on a thoroughly depressing afternoon, Leeds were dumped

out of the FA Cup on their home soil by Manchester City. The game was

marred by crowd trouble as United fans poured onto the field to confront

City keeper Joe Corrigan after the visitors scored. Every bit as ugly

was the angry scuffle between Gordon McQueen and David Harvey as the pair

waited for a City corner. After the game, the FA imposed a ban on United playing FA Cup games at

Elland Road and the club fined McQueen for his lack of discipline. Within

days he had left to join close friend Jordan at Old Trafford with Leeds

pocketing £450,000. The fee was little consolation, and United fans were

irate at seeing two of their star men moving to such bitter rivals. It

sent an unmistakable signal that the Yorkshire club were no longer members

of the game's elite. Blackpool's Paul Hart arrived in March as a £330,000 replacement for

McQueen. He enjoyed some difficult early weeks, prompting more unrest

from the fans, though he later found his true form in a United shirt and

became a defensive mainstay. By the time of Hart's signing, Leeds' season was drifting to a disappointing

conclusion. They had reached the League Cup semi finals, but lost both

legs to a fine Nottingham Forest side. In the League, they finished ninth,

a minor improvement on the previous season, but still an unsatisfactory

outcome for some of the most passionate supporters in the country. The United directors, spoiled by the untrammelled success they enjoyed

for so long with Don Revie, decided that Jimmy Armfield could take the

club no further and sacked him a month before the start of the 1978/79

campaign. It was something of a surprise, for Armfield had made a decent

fist of the prickly task of replacing Don Revie's golden generation. After a brief period with assistant manager Maurice Lindley at the helm,

the board recruited former Celtic supremo Jock Stein to replace Armfield.

The Scot, who had led the Glasgow club to European Cup glory in 1967,

had been replaced at Parkhead by former skipper Billy McNeill and he was

disaffected with the Glasgow giants. It was generally accepted that Stein's

move was motivated more by resentment against his former employers than

any great desire to restore United's fortunes. He had previously rejected a number of offers from other English clubs

and at 55 he had no real hunger to uproot his family, but could not bear

to be offered a backroom job at Celtic and he accepted the United position

on August 21. It was reported that Stein hadn't been Leeds' first choice;

apparently Lawrie McMenemy had turned down an offer, leaving the directors

to There were high hopes at Elland Road that Stein, with his experience

and standing in the game, could take United back to the very top, but

it was soon clear that his heart wasn't in the move. He never signed a

contract and quit after six weeks to take control of the Scottish national

side. Sunderland manager Jimmy Adamson, who had come close to being appointed

England manager in the Sixties as replacement to Walter Winterbottom,

was Stein's successor, taking up the reins in October. Adamson inherited a difficult situation: the side had won just three

of its first ten league fixtures, and two of its greatest stalwarts, Paul

Reaney and Allan Clarke, had ended illustrious associations with Elland

Road, moving on to Bradford City and Barnsley respectively. The new manager

took a pragmatic early approach, claiming 'I want to see Leeds win first

and entertain second.' The early signs were good as Adamson hinted at being able to inspire

the side to better things. Under his guidance, United enjoyed a 16-game

unbeaten run in the league. That initial period included a hard-earned

draw away to champions elect Liverpool at the start of November, with

Bob Paisley's men requiring a late penalty to gain a share of the points. Despite his initial caution, Adamson also got Leeds playing some attractive

football; inspired by Tony Currie, they fought back from being 3-1 down

in the FA Cup to West Bromwich Albion to earn a 3-3 draw before going

out in a replay. United tailed off towards the end of the campaign, but managed to secure

a fifth place spot and a return to European competition by qualifying

for the UEFA Cup. They also reached the League Cup semi-finals, and looked a good bet for

Wembley when they took a 2-0 lead in the first leg at home to Southampton.

But the Saints fought back strongly to earn a 2-2 draw and then won 1-0

in the return at the Dell to eliminate United. Adamson set about the challenging task of reshaping his playing strength.

David Stewart and Peter Lorimer departed before the end of the campaign

and the summer months brought further exits in the shape of Tony Currie,

Frank Gray and John Hawley. Adamson had already paid out £357,000, a record

for an English full-back, when signing Kevin Hird from Blackburn in March,

and he continued to splash out the cash, signing Alan Curtis, Brian Greenhoff,

Gary Hamson, Wayne Entwistle and Jeff Chandler in the close season. These were modest names after those that had graced Don Revie's team

sheets. Paul Madeley, David Harvey, Eddie Gray and Trevor Cherry remained

in situ to preserve a link with the Revie years, but United were in the

throes of transition as the decade drew to a close. The early months of

Adamson's reign hinted they would be able to compete once more at the

highest level, with the promise of European competition getting the juices

going, but there was an unmistakable air of apprehension around Elland

Road as the decade drew to a close.  of

a remarkable rise to the summit that had begun with the club verging on

relegation to Division Three for the first time at the start of his tenure.

of

a remarkable rise to the summit that had begun with the club verging on

relegation to Division Three for the first time at the start of his tenure. United

board were every bit as forthright in their comments and defended the

supporters' actions, prompting criticism from local businessmen and sanctions

from the Football League.

United

board were every bit as forthright in their comments and defended the

supporters' actions, prompting criticism from local businessmen and sanctions

from the Football League. place.

place. permanent appointment.

permanent appointment. Gwyn

Thomas as United were rocked by a succession of injury problems.

Gwyn

Thomas as United were rocked by a succession of injury problems. pursue

their next best option.

pursue

their next best option.